Cinema can transport audiences – and help them see the world with new eyes

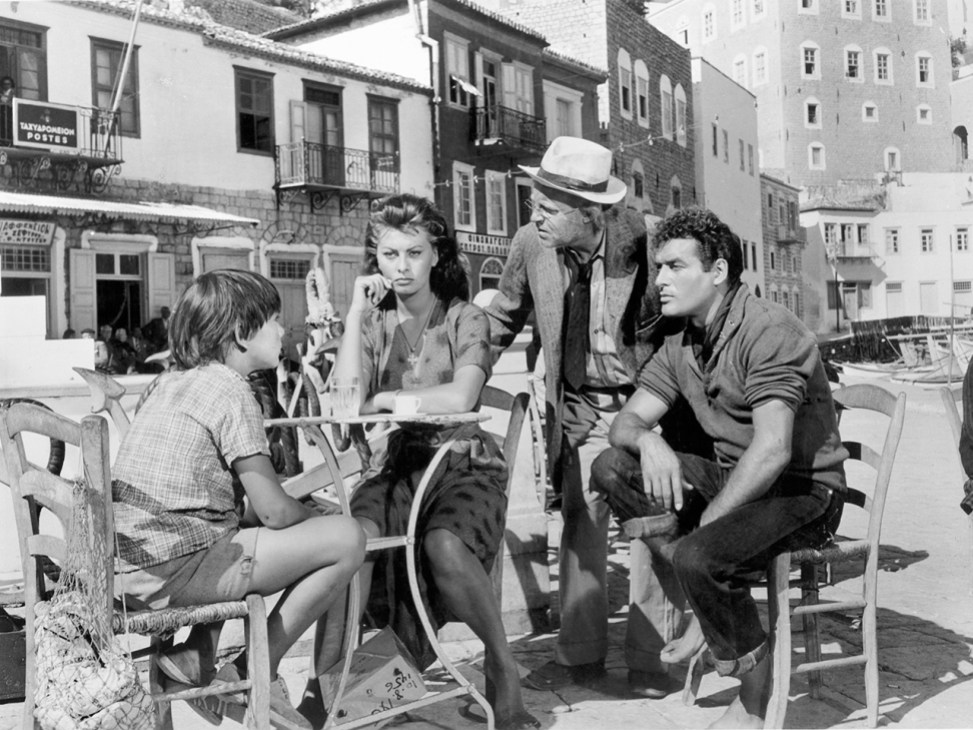

With a smile, George Koukoudakis, the mayor of Hydra, nods to a heavy bronze sculpture on his desk. The piece, which depicts a boy sitting atop a dolphin, was gifted to the island’s town hall in the mid-1950s by members of a film crew from US film studio 20th Century Fox. They, along with a young Sophia Loren, had disembarked on this Saronic island to shoot Jean Negulesco’s romantic drama Boy on a Dolphin, released in 1957. It was the Italian starlet’s debut English-language role and the first Hollywood production to be shot in Greece. Like many of his compatriots, Koukoudakis believes that the picture not only changed the way that the world saw his country but also helped to birth its tourism industry. “The film had such an impact,” he says. “People saw Greece in a different way and wanted to visit. It was the Hollywood effect.”

A restored version of Boy on a Dolphin has been rereleased in Greek cinemas this summer. Almost 70 years on, the scenes of Hydra in glorious DeLuxe Color continue to stir the soul. Athens, Rhodes and Delos also feature, bathed in sun and set against the shimmering sea. One can imagine the effect that such sights must have had on postwar audiences across the globe. Films have the power to take viewers somewhere new, serving as ambassadors for places – think the New York of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the Hong Kong of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love or even Danny Boyle’s dream-like vision of Thailand in The Beach.

Cinema was once a celebration of travel, journeys and placemaking. If this feels inaccurate today, it’s partly because the industry has become less reliant on location shoots and increasingly mindful of budgets. Generic backdrops or green screens can ape the grandeur of a Manhattan crosswalk at a fraction of the cost. Meanwhile, generous tax rebates are luring productions to vast sets in countries such as Saudi Arabia. And budding filmmakers can always take the short cuts offered by generative AI.

It might be the case that today’s cinemagoers are simply better travelled than postwar audiences and that exotic locales are no longer enough to attract them. But don’t underestimate the ability of a major location shoot to bring fresh energy to a place. In Hydra – an island that’s proudly car-free and has remained relatively unchanged for decades – the power of such placemaking endures. The filming of Boy on a Dolphin is part of its lore and older locals, some of whom were recruited as extras during production, still tell stories of what happened when the big Hollywood crew and actors came to town.

In a memoir by Australian writer Charmian Clift, one of the many artists who flocked to the island in the 1950s and 1960s, she describes how Loren’s star appeal caused a flurry on the minuscule island that didn’t even have running water at the time. It’s a reminder to young directors and filmmakers that there’s a big world out there – and plenty more places to put on the map, far beyond the well-documented boulevards of Los Angeles or Paris.

In the Saronic Islands, Loren-loving Greeks are indulging in nostalgia as they settle into cinema seats to rewatch the remastered Boy on a Dolphin. Go and see it yourself for a taste of Hollywood’s golden age, when filmmakers wanted to whisk you away to somewhere new.

Fitzgerald is Monocle’s North Africa correspondent. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.