How decadence foreshadows decline and the enduring appeal of ‘Wuthering Heights’

Emerald Fennell’s new adaptation of Emily Brontë’s classic novel has divided critics and audiences alike. Scholars Dr Jessica Gossling and Dr Alice Condé reflect on decadence and why ‘Wuthering Heights’ is so often misunderstood.

It seems as though Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel Wuthering Heights has been reimagined as many times as it has been misunderstood. The official trailer for Emerald Fennell’s adaptation claimed that the film was “inspired by the greatest love story of all time”. Released just in time for Valentine’s Day, it promises an extravagant, erotically charged take on the classic.

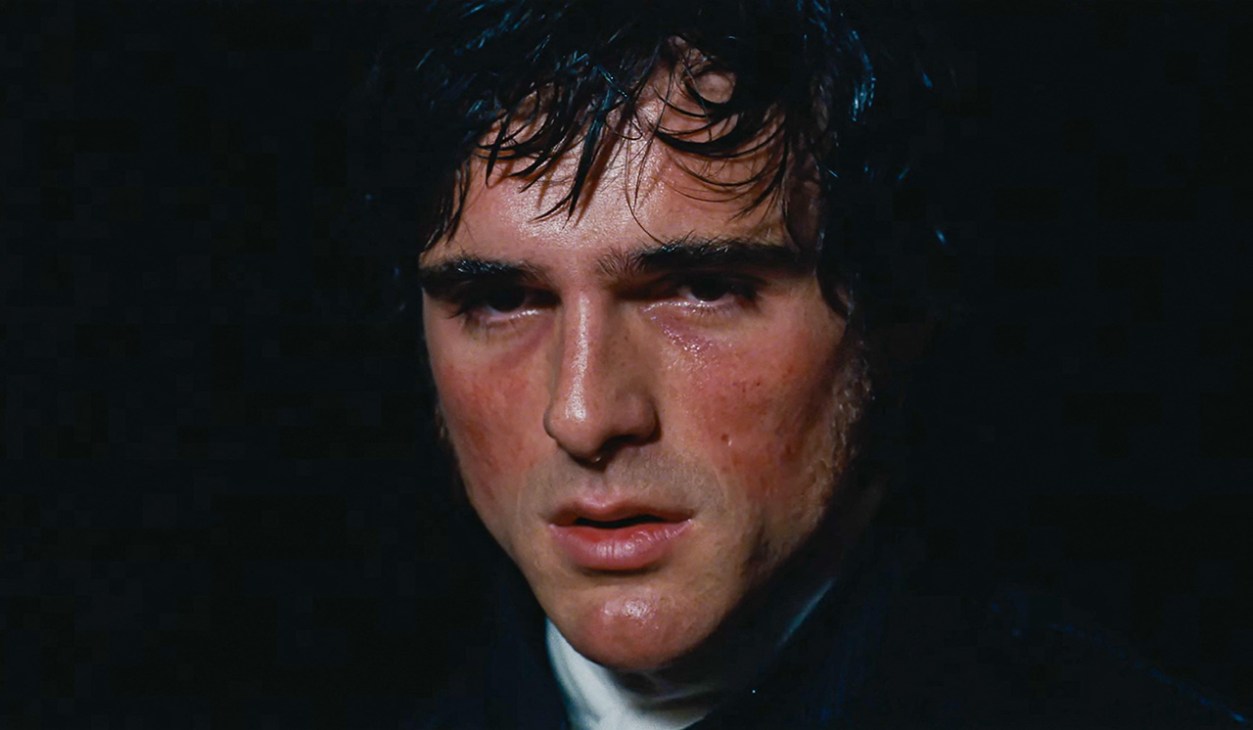

The novel’s reputation as a tempestuous romance sits uneasily alongside a book that is, at heart, a Gothic tale of desire, class, race and intergenerational trauma. Fennell’s highly anticipated film has already drawn controversy from critics and audiences, not just for its focus on romance but particularly for casting a white actor, Jacob Elordi, to play a character described in the original text as a “dark-skinned gypsy in aspect”.

Any adaptation will inevitably reveal much about the moment in which it is made, and while we are seeing a return to more conservative values in global politics, Fennell’s hedonistic version of this 19th-century work is a somewhat controversial rebellion against those values.

To unpack the Saltburn director’s take on Wuthering Heights, as well as the role of decadence in the novel and why it is so misunderstood, Georgina Godwin was joined on Monocle on Saturday by Dr Jessica Gossling and Dr Alice Condé of the Decadence Research Centre at Goldsmiths, University of London.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What is decadence?

Alice Condé (AC): The way we conceptualise it at Goldsmiths is as a literary, artistic tradition that emerged out of the 19th century; a rebellious countercurrent that’s running alongside a lot of progress and technology. It is a morose response to modernity. It emerges at times of social and political crisis as well, and responds to those. We’re living in a decadent age now. So we’re trying to unyoke it from the 19th century and consider ways in which our culture is decadent, along with artistic responses to that.

How true is the film to the book? And does it matter?

Jessica Gossling (JG): Adaptations are really interesting because of what they tell us about their cultural moment, and so what Fennell has decided to leave out or keep in is quite fascinating. If you’re going to watch this film because you love the novel, you’ll be disappointed. But if you want to watch it because you love the vibes and the essence of what we think of as Victorian – this kind of oversexed, bodice-ripping lusciousness – then I think it’s a great film.

AC: I agree. It’s not a faithful adaptation, and I don’t think Fennell has claimed it is such. But she says that she was trying to adapt the novel to correspond with her first reading of it at age 14. It’s a complex, nuanced novel, which actually at its heart is not a romance. It’s incredibly harrowing to read. Every page you turn, something more horrible happens to the characters. But what Fennell has done is take forward the enduring romantic appeal of Heathcliff and Cathy’s doomed relationship, and that is something that many younger people might respond to on first reading.

Do you think the novel is capable of doing psychological damage to little girls or teenagers who found Heathcliff incredibly sexy and the story just compelling?

AC: That trope has persisted. Personally, that wasn’t what I took from it at all. What endured with me was the ghost scene at the very beginning of the novel, where what we see is Heathcliff’s outpouring of emotion. For a century very much known for its [particular] kind of emotional restraint, it’s incredibly groundbreaking and quite sensitively done on Brontë’s part.

What about the controversial race-blind casting?

JG: It’s so different to the novel that the casting decision is the easiest thing to latch on to in terms of what’s problematic about this adaptation. But also, Fennell strips out the sibling rivalry, incest and animal abuse, so there are lots of other important topics that are also removed. The only thing that remains [of the novel] in the film are some Sparknotes quotes and everything else is very much about how we feel Wuthering Heights should be. For example, there are references to Kate Bush in there. Fennell’s Heathcliff is completely chastised; he’s not the wolfish creature that Brontë describes at all.

Gothic novels often feature gloomy manor settings, eerie, sometimes supernatural elements and characters haunted by a dark past. Was it sexy? Did we get a lot of Yorkshire scenery?

JG: The movie has predominantly been filmed on a set, so it is like an old Hollywood movie in that way. They could control the weather, the lighting, everything, so it doesn’t have that wild naturalness that I would associate with Gothic fiction. It’s very staged. It reminded us of Beetlejuice in a way, with these very strange, anachronistic houses against an almost plastic background.

I’ve been running through preceding periods of decadence in my mind. The roaring 1920s, Weimar Germany. We know what came out of these periods, and, if we’re in another period of decadence now, do you see history repeating itself? What triggers the arrival and departure of such periods?

AC: Yes, absolutely. Those examples that you mentioned are transitional moments on the threshold of decline. The 19th century decadent period is quite interesting because there were these fears of decline and cultural degeneration. That’s why there were such attacks on writers such as Oscar Wilde for his perceived degeneracy, his queerness, his effeminacy. When we tipped into the 20th century, we did end up in these moments of collapse but not quite in the way that the critics of decadence in the 19th century imagined.

To hear the full interview, tune in to ‘Monocle on Saturday’.