Inside Sweden’s fight to protect public-service broadcasting

Across Europe, public-service media faces pressure from hostile commercial and ideological forces. We go behind the scenes in the Nordic nation’s newsrooms to see how its journalists are fighting back.

You wouldn’t guess that weatherman Nils Holmqvist has already been at work for nearly five hours when he riffs on the day’s forecast just after 08.00. The meteorologist is perky, charming and on point as he makes his contribution to Morgonstudion (The Morning Studio), which will run live for the next two hours. “I’m usually a favourite at weddings – I can really talk about the weather,” says Holmqvist.

The waters are calm at Sveriges Television’s Studio 5, where the morning team of presenters, technicians and camera operators runs the show with seamless professionalism. But storm clouds have been gathering behind the scenes at Sweden’s three public media companies: Sveriges Television (SVT), Sveriges Radio (SR) and educational-content provider Sveriges Utbildningsradio. At first glance all seems well: the current broadcasting permit is set to be renewed for another eight years at the end of 2025. A new law that will enshrine the definition of public-service broadcasting as being free from political, commercial or religious interference will also soon come into effect.

Yet behind the scenes, there are problems brewing. Some commentators, including prominent journalist and author Janerik Larsson, believe Swedish public-service media will become obsolete. “People don’t gather around the campfire in the same way as we used to,” he says. “It has nothing to do with content. It’s just that we consume media differently today.”

Critics believe that public-service companies are gaining an unfair advantage over other media players because they have guaranteed financing. Meanwhile, the government wants to cut back on what it describes as bloated organisations. In response, management at the companies say that the government’s new proposed financing model of tweaking the allocation of tax funds (beginning with a higher sum that will be reduced in phases) will force additional savings. In the past two years, more than 200 journalists have been laid off across the three broadcasters.

Management at SR has also expressed dismay at the rising costs of analogue transmission over state-run network Teracom, adding to an already stretched budget. That cost could swell further now that commercial broadcaster TV4 has announced that it is going 100 per cent digital, leaving the public-service broadcasters to foot the entire analogue bill. In addition, the government wants to create an investigative panel to explore the impartiality of Sweden’s public-service companies in response to critics who say that there is a left-leaning bias at play. The proposal has ratcheted up the debate over the degrees of separation between the state and the broadcasters.

“Right now, public-service media in Sweden faces political enmity,” says Fredrik Stiernstedt, professor of media and communications at Södertörn University in Stockholm. “The government wants to rein it in. It’s an old political project of the right that now has air under its wings.”

Yet Stiernstedt points out that the picture in other European nations is worse. Reporters Without Borders describes European public-service media as being in crisis. Across the region, funding is being called into question as broadcasters compete with digital platforms. In Italy and Hungary, public broadcasters are increasingly being used as political instruments. In Poland and the Czech Republic, there has been a direct state takeover.

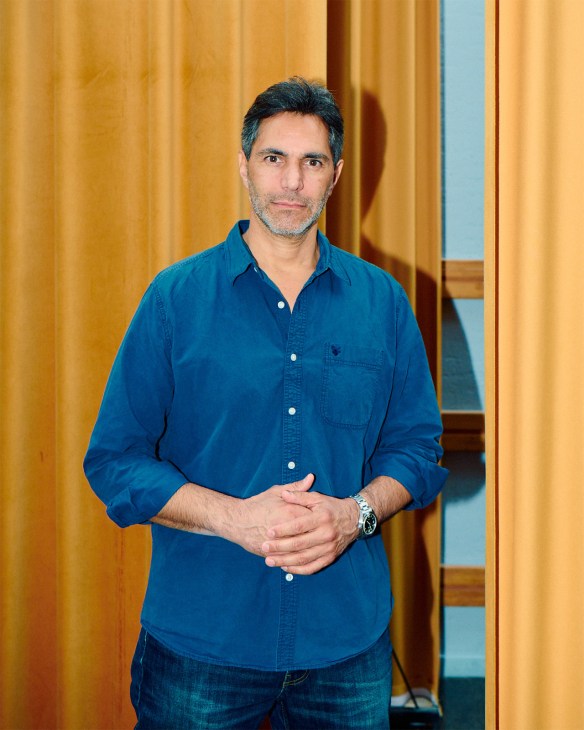

In August new legislation came into effect in the EU as a prospective antidote to these trends. Among other safeguards, the European Media Freedom Act sets out to protect media pluralism, editorial independence and transparency of media ownership to ensure the free functioning of public-service media in the EU. “It’s probably the most advanced media legislation ever created because it tackles several issues,” says Marius Dragomir, the director of a global think tank focused on the study of media organisations and a co-creator of online database State Media Monitor. But he isn’t very hopeful about its impact. “The act won’t have any effect whatsoever,” he says. “For example, Hungary will adopt the legislation but it won’t be implemented – at least, not under the current government.”

Dragomir believes that the sector still fulfils an important mission in Europe “but corruption will continue to be an issue for free and fair reporting,” he says. “Oligarchs buy media outlets and manipulate them. The new law will not change that.”

Despite the challenges, the conflict in Ukraine has brought the issue into sharper focus in Sweden and the Nordics more widely. The country has been expeditiously rebuilding its dismantled military apparatus to be ready to fight should the need present itself. “Even those who believe that we don’t need to be there editorially understand that we need to exist for the safety of the nation,” says Cilla Benkö, the CEO of SR. “If, God forbid, there should be a war in Sweden, SR might be the only media company in the country that can still transmit. We’ll keep broadcasting, even if the lights go out.”

Wearing an understated outfit and with her curly red hair pulled into a ponytail, Benkö sits in a sun-dappled office overlooking the rooftops of Östermalm in Stockholm. “Until now, we have been under varying degrees of economic pressure, depending on who has been in power,” she says. “But we are now moving in the direction of being under pressure politically as well as financially.”

Benkö, who started as a sports reporter 40 years ago, has had a lot of practice arguing the case for SR’s unencumbered independence and its long-term survival. “While we face the gargantuan challenge of competing with global digital-media consumption and tech giants, we also have to defend our existence in a way that we didn’t have to before,” she says. “All the while, we perceive that the Swedish people want more free and independent media. They want to be sure that what they hear is true. They turn to us because they trust our output.”

Of a population of 10.6 million people, 7.4 million listen to SR’s four main and 25 regional stations across the country every week, on both FM and digital platforms. It’s proof that, despite challenges for the overall organisation, SR’s radio programmes continue to be hugely popular.

SR celebrated its centenary this year. Its cavernous entrance reopened in time for the summer anniversary party, with upgraded security features and a fresh look. The overall refurbishment of Radiohuset (The Radio House), a concrete-and-glass monolith from 1962, has been 25 years in the making and is incomplete. There remains a neglected feel in the beating heart of SR’s news hub, Ekot (The Echo); its show has been on air since 1937. Eventually the entire Ekot team will move into a more expansive newsroom.

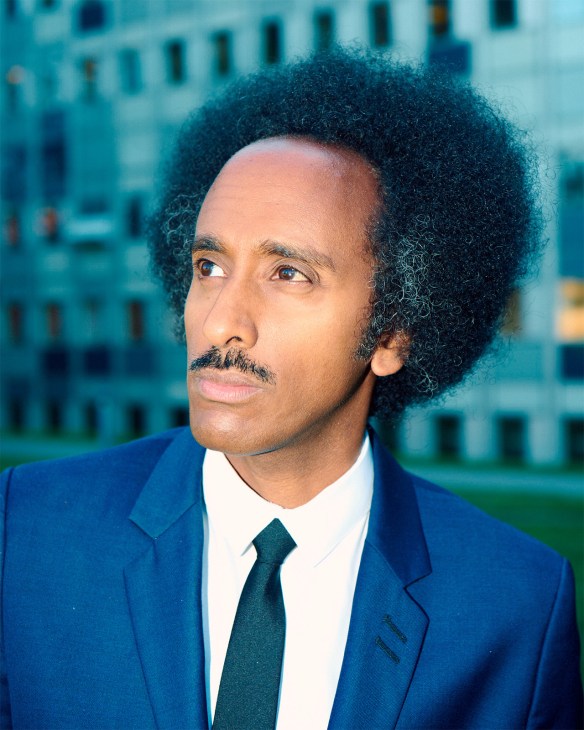

“We’re on borrowed time,” says Billy Abraha, a producer at Ekot. “We have developed our digital content enormously over the past few years. We’ve improved SR’s app and created great content on the landing page that complements the output on FM.” Despite the digital transformation, Abraha is cautious about the future. “It’s tricky to say what things will look like going forward when we’re not sure about funding levels and how they will affect staff,” he says.

Abraha’s colleague Helena Gissén, who joined Ekot as a political commentator after 25 years at commercial broadcaster TV4, agrees that the mood at work is at times subdued. “At TV4 we got used to savings packages every few years,” she says. “People are not used to that here and many are worried about more budget cuts.”

On call to provide analysis around the clock, Gissén has just signed off her shift on P1 Morgon, SR’s most popular programme with a reach of 900,000 daily listeners. On today’s show, Gissén commented on the legal case against Henrik Landerholm, a former national security adviser accused of leaving classified documents at a conference centre. “In the end, we do this work for the public,” she says. “That is why we are here.”

In the newsroom at SVT, there is a reassuring hum of voices and engaged prepping for the day’s shows. The journalists, producers and editors are back from their morning meetings. The head of SVT news, Karin Ekman, delivers an update on the segments that did well over the weekend and those that could have done better, and welcomes two new political reporters into the fold.

The teams then huddle together in editorial discussions specific to every news programme, deciding on what to broadcast over the next 12 hours. The big-ticket item on the agenda for the flagship news programme, Aktuellt, which airs every weeknight at 21.00, is an interview with Ukraine’s former foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba.

A large portion (81 per cent) of Swedes watch SVT every week, which is broadcast from Stockholm, Malmö, Gothenburg and Umeå in the north. About one million viewers over the age of 25 watch evening news programmes Aktuellt and Rapport. But despite high ratings, SVT journalists understand that they need to remain in the viewers’ good graces and prove themselves worthy of the taxpayers’ kronor that keeps the lights on in the studios.

“It’s up to the public to decide through their elected representatives what they want our service to be,” says Jon Nilsson, a longstanding presenter of Aktuellt. “Even if I believe that the work that we do is important, people are allowed to voice opinions on how much it should cost to produce. So far, we are still here – alive and kicking.”

As his Aktuellt co-host Cecilia Gralde gets ready for the interview with Kuleba, she talks about the need to stay connected with the public. “We constantly have to renew ourselves; we can never stay idle,” she says. “The goal is to be engaged with our audiences.” Although Gralde has extensive experience as a news journalist – she began her career in 1998 – she took on a temporary posting as SVT’s Europe correspondent over the summer. While in that role, she covered, among other events, the pride parade in Budapest, wildfires in Spain and the Nato meeting in The Hague. She was looking “to experience what it’s like on the ground, being questioned from the studio back home”, she says.

In contrast, Gralde’s colleague Samir abu Eid is on his first day back at headquarters after 15 years posted in the Middle East. He is trundling through the newsroom on crutches because of a bandaged foot. “It’s not what you think,” he says. “I didn’t get hurt covering Gaza. I was playing basketball.” Abu Eid has become a familiar face to Swedes who watched his Middle East reporting almost daily. Today he is on his way to provide expert commentary on the region live from Studio 5. He confesses that he is already longing to be back in the field. “It’s very odd to be asked if I’ve brought a packed lunch to the office,” he says with a chuckle.

Whereas SVT’s former Middle East correspondent might be itching to get back into the thick of things, his boss has a resolve to stay at the helm, steering the ship. Ekman has a firm vision for the new direction of SVT news. “Public-service broadcasting isn’t immune to challenges,” she says. The focus is on capturing younger audiences by, without abandoning facts, moving away from doom-and-gloom journalism as much as possible towards solutions-focused reporting and “storytelling”. Though difficulties appear to be coming from all sides, Ekman is clear in her belief in the unique role played by public-service media in today’s world. “We have the experience and heft to continue to be the trustworthy haven that we always have been,” she says.