How do you move the Dutch national photography collection? Frame by frame

Peek behind the scenes as the Nederlands Fotomuseum gracefully transports 6.5 million works into its new home on Rotterdam’s waterfront.

At 10.00 on a bright and bitterly cold November day, Monocle is in one of Rotterdam’s biggest harbourside warehouses. Outside, two removal vans begin unloading pallets full of some of the country’s most valuable works of photography. The Nederlands Fotomuseum – the national custodian of 6.5 million photographs, negatives and objects – is moving into its new home: Pakhuis Santos, a former coffee warehouse.

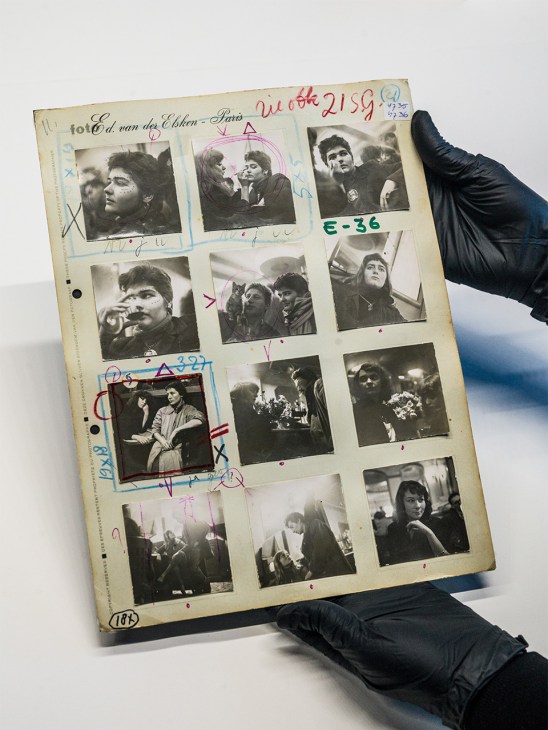

Its collection is one of the world’s largest and is predicted to grow to 7.5 million objects by 2028. It focuses on work by Dutch photographers as well as those who spent extended periods in the Netherlands. Loaded onto the back of those vans are images that tell the nation’s story, such as Bernard F Eilers’s documentation of the Amsterdam School of architecture and Augusta Curiel’s visual records of life in Suriname under Dutch colonial rule. The collection features archives of more than 175 photographers – Ata Kandó, Esther Kroon and Ed van der Elsken among them. Stored with the images are a large number of glass-plate negatives and contact sheets that reveal the processes behind the artistry. Alongside Ed van der Elsken’s iconic photographs of young Parisians in the 1950s are scrappy contact sheets adorned with his colourful scribbles that mark his favourite shots or how he wanted an image to be cropped. “We go to great lengths to consider how these photographers would have liked us to display their work,” says Nederlands Fotomuseum’s head of collections, Martijn van den Broek.

The collection also includes a series of portraits by Erwin Olaf, in which he burnt the colour negatives with a lighter to dramatic effect. There are ways, then, to make this notoriously fragile artform even more so. But the operation to move the works into the Santos warehouse is a delicate affair.

Dutch firm Imming Logistics Fine Art is handling the operation, overseen by Nederlands Fotomuseum’s Cobie Hijma. Inside the vans, the glass plates face the direction of travel to prevent any jolts from damaging them. Hijma and her team have sketched detailed layouts of the vehicles’ interiors to figure out the most efficient way to transport the works. While the country’s inclement weather was a cause for concern, it has luckily only rained on a single day during the six-week transportation schedule. “It was a team-building experience like no other,” says Hijma.

As precious plates, pallets and boxes are unloaded from the vehicles, Van den Broek is on hand to oversee what feels like a careful game of Tetris. All materials were moved directly to their permanent destinations in climate-controlled storage spaces as quickly as possible (units containing film negatives are typically regulated at 4C). “If it’s not regulated properly, the changes in temperature as we move the archives can cause a build-up in condensation,” says Van den Broek. “It’s a highly technical exercise.”

The new museum site, which was built between 1901 and 1902, was originally used to store coffee imported from the Brazilian city of Santos. It then sat vacant for more than 60 years, followed by an aborted attempt to transform it into a design showroom. In 2023 the philanthropic Droom en Daad cultural foundation purchased the building to ensure that the Nederlands Fotomuseum could have a purpose-built space. And it’s a good thing too: the collection has almost doubled in size since its last move in 2007, which was to the Las Palmas building just a 15-minute walk away.

Pakhuis Santos is one of the few buildings in Rotterdam to survive the Second World War. Its striking concrete and cast-iron structure has now been spruced up by local studio Wdjarchitecten and Hamburg-based Renner Hainke Wirth Zirn Architekten. The renovations have resulted in a rooftop extension and the opening up of the central atrium, which has allowed natural light to filter through each of the five storeys (as well as the restaurant on the sixth), transforming the dingy warehouse into a structure that breathes while retaining its beaux arts soul.

When it opens on 7 February, Nederlands Fotomuseum will join the newly opened Fenix Museum of Migration in the Rijnhaven district, a neighbourhood undergoing major redevelopment. While the archives might document the ups and downs of the country’s history, this move is about looking to the future. “Photography is an irreplaceable record of who we are,” says Van den Broek. “Yet is is among the most fragile forms of cultural heritage, making its protection not just a responsibility but a necessity.”

nederlandsfotomuseum.nl