Issues

Fashion’s 2026 reset: What the industry leaders are forecasting for the year ahead

With 15 houses debuting fresh looks under newly appointed creative directors, 2025 was supposed to be fashion’s big moment of change. The industry has collectively decided to put clunky sneakers, all-beige looks and streetwear behind it.

So what does that mean for how we’ll be dressing in the year ahead? “When I think about the new season, I picture a post-luxury world, a return to elegance and interesting colours,” says Hirofumi Kurino, co-founder and senior adviser of Japanese retailer United Arrows. After surveying catwalks, showrooms and exhibitions in Florence, London, Milan and Paris in late 2025, he began to see a subtle shift. There might not be a single new look defining the season (though Jonathan Anderson’s deconstructed Dior Bar jacket is a strong contender) but there’s a new set of priorities: fewer logos and more creative, human-centric designs.

Japanese designer Satoshi Kuwata’s Milan-based label Setchu is a brand to watch in 2026. “Satoshi trained on Savile Row and never uses the word ‘trend’,” says Kurino. “I have a coat by him and it can be folded flat. You can see how deeply he thinks about structure and technique.” Other Japanese designers are also having a global impact, including Auralee, known for its masterful command of colour, and Satoshi Kondo of Homme Plissé Issey Miyake. Updating your look for the new year could be as simple as tying a bright-green sweater over a camel coat or layering a yellow trench coat over a T-shirt in a similar hue.

One name who will be setting the agenda next year is London-based Grace Wales Bonner, who was recently appointed as Hermès’s new menswear creative director. For her eponymous label, which turned 10 this year, she offers Crombie coats, elegant short suits and polo shirts inspired by UK sartorial traditions for spring/summer 2026.

“We have been overproducing and overconsuming for so long,” says Kurino. “Designers are now rethinking the system and not just selling products for the sake of selling.” Kurino’s words capture a collective fatigue with aggressive commercialisation and the endless search for novelty. Seasons change but simply knowing that you’re wearing what you like – as well as caring about where and how it’s made – has always been the greatest luxury.

Natalie Theodosi is Monocle’s fashion director.

Inside Hanaholmen, the secretive Nordic retreat where diplomats shape Europe’s future

It’s a crisp autumn morning on Hanaholmen as military officers, politicians and think-tank members sip coffee beside the icy Baltic waters. All are either Finnish or Swedish and are performing a ritual that has taken place here every few months for the past 50 years. This small island, a few minutes by boat from downtown Helsinki, is home to the Swedish-Finnish Cultural Centre, a literal (and littoral) manifestation of the two Nordic countries’ rock-solid ties.

Monocle is here to attend the Hanating defence and security policy forum, an annual event that aims to further sync already close defence ties. Inside, sheltered from the chilly winds behind floor-to-ceiling windows, attendees – who include both countries’ defence ministers – are discussing drone warfare, hybrid threats and the state of Nordic defence co-operation. Outside, on a terrace lined with stone sculptures and fringed by tall pine trees, the air feels lighter, as does the conversation. “I took a dip in the sea last night, followed by a sauna – that’s how you do it, right?” we overhear a Swedish diplomat ask a Finnish counterpart.

Hanaholmen has always been a place where serious discussion takes place in a calm environment. “It’s not just a building,” says Charly Salonius-Pasternak, the CEO of geopolitics consultancy Nordic West Office and a longtime visitor. “It represents the bilateral relationship. It’s a place where ministers, researchers and bankers meet, but it’s also somewhere you can go and dip your toes in the water. It’s not an embassy or a government office. It’s a neutral third space with rich cultural layers.”

Founded in 1975 on a verdant island in the Gulf of Finland, Hanaholmen was created as a gesture of reconciliation and trust. Sweden had forgiven a substantial chunk of Finland’s postwar debt and Helsinki’s way of saying thank you was to invest its goodwill in something lasting – a shared space for dialogue and co-operation. The result is extremely Nordic: a low-slung, honey-toned complex of modernist glass-and-concrete buildings designed by Finnish architect Veikko Malmio. It’s a notable example of 1970s design from the region that still looks contemporary.

Sitting in an orange Yrjö Kukkapuro Junior 417 chair, Hanaholmen’s CEO for more than 20 years, Gunvor Kronman, reflects on the centre’s mission. “Hanaholmen was founded 50 years ago to make sure that the relationship between Finland and Sweden continues to grow,” she says. “It covers all parts of society. We were called a cultural centre for practical reasons during the Cold War but our mandate has always been broad. It includes everything from defence and security to economic development.”

Over the years, this mandate has been expanded further. Kronman describes Hanaholmen as “semi-official, semi-private”, an organisation that can discuss things that are too sensitive for statespeople to speak about publicly but too important to overlook. “We can take initiatives that governments can’t,” she says. “If we fail, it’s our failure. If we succeed, it’s our partner’s success.” Among its programmes are the Hanaholmen Initiative, a crisis-preparedness scheme launched during the coronavirus pandemic; Tandem Leadership, a year-long training network for emerging decision-makers; and Tandem Forest Values, a research collaboration on sustainable forestry. “We believe in personal relationships,” says Kronman. “When people know each other, there’s trust. Trust is the Nordic gold.”

This is built not only through conversation but also setting. Hanaholmen’s interiors exemplify Nordic simplicity: pale wood and clean lines, with furniture and fittings designed by Finnish and Swedish icons. The island houses more than 300 unique artworks, its own gallery and a sculpture park. “Each artist spends time here and picks their location,” says Kronman. “It takes about a year from idea to installation. We don’t want to rush the process.” A recent renovation, completed in 2017 by Helsinki-based design studio KOKO3, honoured the building’s 1970s identity while updating it for 21st-century use. “Moving from the centre of Helsinki to Hanaholmen feels like entering into a different rhythm,” says Jukka Halminen, a partner at KOKO3. “It’s similar to a Finnish sauna ritual: you slow down, breathe and calm down. We wanted the design to support that feeling.”

KOKO3 used natural materials such as brass, oak and stone to keep the original texture of the place, while adding touches from classic Swedish design house Svenskt Tenn to brighten and warm the interiors. The result is neither nostalgic nor sleekly new; it feels lived-in, timeless and quietly Nordic. “We wanted to keep the dialogue between Finland and Sweden visible in the design choices,” says Halminen. “It’s about balance: heritage with lightness, seriousness with joy.” You can feel the same balance at Plats, the island’s restaurant. Hanaholmen’s in-house fisherman, Christer Hackman, catches perch and pike, forages mushrooms and berries, and supplies the kitchen with wild herbs. The menu marries Finnish ingredients with classic Swedish dishes, served in dining rooms that glow with light timber and the burning logs of fitted fireplaces. “Food is an essential part of Hanaholmen,” says Kronman. “It creates a different atmosphere. Sharing a meal changes the tone of a political discussion.”

For those not lucky enough to be a Nordic diplomat, Hanaholmen is also a hotel. The swimming pool and glass sauna, which looks out to sea, are among the most popular in the Finnish capital. “We might be small [66 rooms] but we’re a significant meeting place,” the hotel’s director, Kai Mattsson, says as he shows Monocle around the building’s top-floor suite. “Every weekday there’s something happening. It can be 200 delegates one day and a honeymooning couple the next.” Mattsson describes the hotel as both an engine and enabler. “The commercial side helps to finance the cultural side but it’s also part of the experience,” he says. “People come here for seminars and to discover the art, the design, the nature. It’s not your typical conference hotel.”

Hanaholmen’s blend of architecture, art and natural beauty reflects the belief that soft power becomes tangible through space. “No matter how tough the subject, we try to maintain integrity and decency in conversation,” says Kronman. “That’s how we contribute to an open, democratic society.” At the Hanating forum, that spirit is writ large. Finland’s defence minister, Antti Häkkänen, and his Swedish counterpart, Pål Jonson, are engaged in discussions that mingle military strategy with cultural diplomacy. “Hard defence must be strong,” Häkkänen tells Monocle. “But the political landscape – how voters and politicians perceive the world – that’s soft power and it’s very important. Institutions such as Hanaholmen keep our societies aligned over issues such as Russia and European security.” His Swedish colleague adds, with a grin, “I mostly work with guns, bombs and hard military power but I still value the cultural exchange that Hanaholmen represents.”

Perhaps no one captures this exchange better than Sweden’s hirsute ambassador to Finland, Peter Ericson. “It’s a tremendous asset for the relationship,” he says, referencing the staff and resources at Hanaholmen’s disposal. “I call it a symbiotic relationship: Hanaholmen is the elephant and we at the embassy are the little bird sitting on its back.” He gestures towards the centre’s lobby, which displays photographs of distinguished visitors, including monarchs, ministers and artists. “It’s independent,” he says. “It isn’t part of official diplomacy. Sweden and Finland supervise it together but it is its own foundation. And it has this formula: bring people from both sides, house them, feed them and give them the space to work together. Fifty years ago, it was mostly a cultural exchange; today, it involves anything from defence and civil preparedness to youth issues or the environment. That’s its strength.”

The seasoned diplomat struggles to think of a similar institution anywhere else in the world. “Hanaholmen is unique,” he says. “An embassy symbolises a country. Hanaholmen symbolises the relationship itself.” This distinction might explain its lasting significance. In a world that is increasingly driven by summits, video calls and transactional diplomacy, it represents something older and subtler – the gradual building of trust through shared experience and conversation. At Hanaholmen, diplomacy isn’t performed but practised. “We believe in identifying the right people who should know each other,” says Kronman. “From that, many good things will come.”

This approach resonates beyond Finland and Sweden. The centre has hosted a range of figures, including the Nordic royal families, prime ministers and popular actors such as Mikael Persbrandt. Fifty years after Hanaholmen was opened by the Swedish king, Carl XVI Gustaf, and Finland’s then-president, Urho Kekkonen, the Nordic region, once viewed as a quiet corner of Europe, now finds itself on the front line of geopolitical change. After decades of neutrality, Finland and Sweden are now NATO members. Defence committees from their respective parliaments meet here regularly; they are doing so on the day that Monocle visits. Amid discussions on deterrence and hybrid warfare, soft power is still the centre’s guiding light. “Hard power is obvious – Ukraine reminds us of that,” says Ericson. “But soft power is what keeps our societies attractive and resilient. We don’t have to deceive people to be liked. We just have to be our best selves.”

Digital diplomacy and rotating presidencies can’t replace the continuity that is offered by a physical site. Hanaholmen’s architecture, art and cuisine aren’t just decorative – they’re part of the dialogue. As the afternoon light dims over the Baltic, the conversation on the terrace shifts from air defence to pan-fried Arctic char. It feels both ordinary and extraordinary – the kind of quiet, human-level contact that supports deep Nordic co-operation.

Radio Shinyabin has found the secret to connecting ever more isolated young people: Late-night broadcasts

It’s 23.00 in Shibuya. Inside a radio control room, a studio engineer is preparing to take one of Japan’s most popular late-night stations on the air. A cornerstone of the country’s media, it runs to the early hours of the morning, bringing its audience along on a six-hour odyssey. Pushing the faders up, the studio manager engages the mics: this is Radio Shinyabin (“Midnight Mail”).

“It’s not a traditional show where users tune in from start to finish,” says Tomoki Sakuma, Radio Shinyabin’s senior producer. Hosted on Japan’s public-service media, Nippon Hoso Kyokai (NHK), this eclectic programme has been running since 1990 and is just one of the country’s many late-night radio shows. “For long-time listeners, the broadcast has become as habitual as eating breakfast,” says Sakuma. “Every hourly time slot has its own fans.” Honed over years on Japanese airwaves, Radio Shinyabin keeps a consistent tone with subtle changes in rhythm and content as the audience rotates through the night. News stories accompany tales of travel; music melts away into reflective discussion.

Across a broadcast, the show can attract three million individuals, with about 600,000 listening at a time. In 2024, Radiko, the Japanese radio streaming app used to access shows from across the country, published a list of its most-listened-to programmes among 10- to 40-year-olds. Late-night shows formed the majority.

It is telling that they thrive in Japan. With rises in loneliness linked to dwindling birthrates, small living spaces and a demanding work culture, growing numbers are flocking to radio in the wee hours to enjoy Radio Shinyabin’s sense of intimacy. “I always imagine that I’m speaking to a specific person,” says Akira Tokuda, who has been one of the show’s anchors for 11 years. “It isn’t one-way; it’s like a conversation.” Sometimes a human voice, wherever they are, can make all the difference.

Comment

Feeling part of a community is more important – and comforting – than ever for young Japanese people, whether they’re night-shift workers or lonely insomniacs.

Can tax breaks create a baby boom? Athens hopes so

“We saw that everything was going to close, so we thought we had to do something,” says Konstantinos Dousikos, a softly spoken Orthodox priest whose parish is the mountain village of Fourna, in the central Greek region of Evrytania. With a median age of 57, Evrytania is officially the oldest region in the EU and Fourna is typical of the demographic crisis that is facing its towns and villages. With the kindergarten facing closure, the 52-year-old priest joined forces with a young schoolteacher to take radical action: offering families from across the country locally raised financial support to relocate. A year on, following the arrival of six new families, Fourna’s youngsters now number 27 and signs of life are trickling back to its steep, fir tree-lined streets. “It truly warms your heart to see children coming for mass on Sunday and running around and laughing in the square. We had missed that,” says Dousikos.

Fourna is not alone in its struggle – Greece is rapidly becoming one of Europe’s oldest countries amid a sharp drop in births and rising life expectancy. More than 700 of the country’s schools have closed this year because of dwindling pupil numbers. Many of these are in rural areas, where the sound of pensioners’ worry beads in otherwise silent cafés is far more common than that of children playing in the streets. After stern warnings by analysts of the implications for the nation, the centre-right government led by Kyriakos Mitsotakis is making an all-out push to encourage people to start families. After years of ad-hoc measures, the Greek prime minister brought out the big guns in September. Warning of the “demographic threat” faced by both Greece and Europe, Mitsotakis announced €1.6bn in tax breaks targeting young families in particular.

From 2026, low-income families with four children will pay no income tax, while property tax will be abolished for villages of fewer than 1,500 residents. These measures build on a €2,400 “baby bonus” for a first child that rises to €3,500 for a fourth – and form part of a sweeping 10-year plan aimed at reviving family life across the country. Despite the evident ambition, experts warn that the task is Herculean. “Births in Greece have collapsed since the 1980s,” the head of the Laboratory for Demographic and Social Analysis at the University of Thessaly, Ifigeneia Kokkali, tells Monocle. This decline is reflected in the overall population, which is expected to drop from 10.4 million to 8.8 million by 2050, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) which has predicted that more than a third of Greece’s population will be over 65 by 2060.

“The demographic trend won’t change overnight,” says Domna Michailidou, the Greek minister for social cohesion and family, from her office in central Athens. In addition to the financial incentives, Michailidou, 38, who had her first child in April, cites a “holistic set of measures” aimed at boosting parenthood and family life. These include more childcare centres, a “neighbourhood babysitters” scheme offering up to €500 a month to local nannies and cheap housing loans for young Greeks.

Numbers behind the shifts in Greece’s demographics

At 1.3, the country’s fertility rate is among the lowest in the EU

Fewer than half as many Greek children are being born as in the 1950s

The population of Greek women of childbearing age fell by 450,000 between 2008 and 2022

Young Greeks leave their parents’ homes later than almost anywhere else in Europe – at an average age of 30.7, compared with the EU average of 26.2

Between 2010 and 2022, more than a million working-age people left Greece; of these, 60 per cent were aged between 25 and 44

But for many, the costs still outweigh the benefits. In a survey last year by independent think tank Dianeosis, six in 10 Greeks aged 25 to 39 said that financial difficulties were their biggest obstacle to starting a family. Housing costs are particularly steep in a country where wages are the third-lowest in the EU, after Bulgaria and Hungary. “I don’t even consider the bonus and state benefits,” says Vasiliki Fokou, a 32-year-old doctor who is working three jobs while waiting for a residency spot in child psychiatry. She cites the cost of living as her cohort’s biggest impediment to parenthood. Despite recent rises in the country’s minimum wage, Greeks pay some of the highest food and energy prices in the EU. “[The new incentives] are a help,” says Fokou. “But they wouldn’t convince me to have a child. It’s a big expense – clothes, nappies, schooling – and life is just so expensive.”

Analysts agree that cash alone won’t fix the problem. “Bonuses are a drop in the ocean,” says Aris Alexopoulos, the head of the OECD’s population dynamics centre, which is based in Crete. Alexopoulos says that lessons should be learnt from countries such as South Korea, which had one of the world’s lowest fertility rates but has recently reversed the trend. After years of failed cash incentives, Seoul instigated a policy overhaul that improved parents’ work-life balance and funded childcare costs and housing. Greece’s 10-year plan is on the right track, Alexopoulos says, but implementation – traditionally a weak spot in the country – will be crucial, requiring a transformation of the economic model and social support system. “It’s not just a birth crisis, it’s about the labour market too,” he adds. “We don’t have young people to work.” He advocates a shift towards the “silver economy”: tapping the skills of workers aged 50 and over to keep treasury coffers in good health.

While Greek policymakers brace for the financial needs of an ageing population, young adults are struggling with the realities of raising children. For many young Greeks, having a child is simply not a priority in the same way it was for their parents. Giorgos Matsoukas, a 44-year-old supervising administrator at a vehicle inspection centre, says that he never really thought about having children and then being child-free became a way of life. “I want to be able to do whatever I want and not sacrifice my lifestyle,” he says. “When I look at my friends who have families, it seems like a lot of hassle.”

As young Greeks postpone or even forego having children, the effects are most visible in rural villages such as Fourna, where ageing populations and youth migration have left formerly flourishing communities in decline. Fourna’s population withered after a wood-processing plant closed in the 1980s and it has lost two-thirds of its population since the 2021 census. Dousikos remembers when trucks loaded with felled trees rumbled from the forest to the plant and there were 26 children in his class at school. But his Facebook posts calling for new residents have triggered hundreds of enquiries. “We have a waiting list of 80 families and another 10 to 15 villages who want our advice,” says 31-year-old Panagiota Diamanti, Fourna’s sole primary school teacher.

The six new families who have moved to Fourna in the past year seem content, though they face new challenges. Christiana Papalevizopoulou and her family were forced to leave their home near Athens after their landlord decided to sell it. The 40-year-old moved with her husband and four children to Fourna in March and got married there in September – the village’s first wedding in 10 years. Papalevizopoulou has been touched by the generosity of locals, who bring her family fresh produce such as eggs and chestnuts. But life in the village is not entirely idyllic. Her husband is applying for a taxi licence but with no doctor in the area and the nearest hospital an hour away, healthcare worries persist.

Projects such as Fourna’s, that have strong local backing, are rare. The government is rolling out its own initiatives to encourage young families to move to rural Greece, though many details are still in the works. One scheme offers €10,000 for relocation to remote regions such as Evros, on the border with Turkey, where populations have thinned out massively in the past few decades. The aim is to extend that programme to more regions. “We want young couples to feel that the state does not leave them on their own but provides them with the tools to build their lives and families in the place they choose to settle,” says Michailidou.

Local support matters but Greece’s demographic crunch looms as an even bigger threat to the national economy. Without serious intervention, the country’s GDP could shrink by 15 per cent by 2050, according to the OECD. Lawmakers have already tried to shore up the labour force, passing controversial rules that allow six-day weeks and 13-hour workdays. But the measures may backfire: a recent survey found that seven in 10 young Greeks view long hours as a major deterrent to starting a family. Money and work pressures aren’t the only hurdles. “My generation has basically accepted that we’re not going to get a pension,” says 29-year-old Ioanna Marouga, who works in an escape room and lives with her parents. “Renting a place of your own is basically impossible – it’s crazily expensive.”

A widely discussed study this year by Kokkali made headlines for its blunt diagnosis: Greece won’t see more children unless living standards and working conditions improve. “The framework of life in Greece today seems to either push young people to emigrate or remain childless,” it noted. Addressing Greece’s demographic decline requires radical reform of deep-rooted social and economic problems. The new raft of incentives signals the government’s ambition, but longer-term planning and more-radical solutions must be on the table, otherwise the Greece of today might not be here in a generation’s time. For this ancient country, it’s an existential issue.

Postcard from the Gulf: Thinking forward to an optimistic year ahead

It’s hard to point to a part of the globe that is changing more quickly than the Gulf. In 2026 and beyond, however, all of that ambition, vision and topdown decision-making that defined the region’s rise will give way to a need for longer-term thinking. The long-delayed, region-wide GCC Railway Project, a route of about 2,000km, is finally edging forward – a symbol of a region learning that integration matters as much as spectacle. In the UAE, Etihad Rail is becoming one of the country’s most consequential projects as road traffic reaches breaking point. A passenger rail service linking Abu Dhabi, Dubai and other key locations could transform daily life.

The UAE is a young nation but there’s plenty of ambition on show on Saadiyat Island. The Louvre Abu Dhabi will be joined by the Zayed National Museum, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and the Natural History Museum in 2026. In them, you will be able to spot the shift from “building tall” to “building meaning”. That said, clustering marquee institutions on a single stretch of coastline could risk concentrating this clout instead of creating vibrant neighbourhoods.

In Dubai, the aspiration to delve beneath the surface rather than merely develop the skyline will only grow. Elon Musk’s Dubai Loop is slated to begin operations by mid-2026. It’s an audacious idea: 17km of tunnelling that could deliver 20,000 passengers in pods through the city’s core every hour. If the Loop works, it could become a model for urban innovation. If not, it might be a symbol of a place that dreams more convincingly than it can build.

Saudi Arabia’s aviation projects, from Riyadh Air to Neom’s futuristic airports, show a nation determined to rise, even as announcements confirm that elements of the Neom megacity project are being scaled back. That in itself feels like maturity – a country learning to scale sensibly and be more realistic.

Oman, one of the Gulf’s quietest players, is proving to be its most courageous, with a plan to introduce personal income tax by 2028. A modest 5 per cent levy on higher earners might not sound radical but it’s an act of fiscal realism. Oman might be pioneering the Gulf’s next era – one in which economic sustainability is valued as highly as the optics.

Inzamam Rashid is Monocle’s Gulf correspondent, based in Dubai.

Italy’s quiet stability and confidence puts it steps ahead of chaotic France

Set the gastronomic rivalry aside and let’s ask a big question: is Italy really the new France? Comparisons between the two cultural big hitters have become unavoidable this year. Both know how to live and eat well and attract vast numbers of tourists. That said, France has foundered economically and politically, while Italy – the home of fiscal blunders and political gaffes – has looked surprisingly stable in comparison.

If proof were needed of the two countries’ fortunes moving in different directions, it came in September when global ratings company Fitch upgraded Italy to BBB+ status, while downgrading France from AA- rating to an A+ (Moody’s gave the country a could-do-better negative outlook in October). The humiliating Louvre robbery a month later seemed like a kick in the crown jewels. That’s before we mull over the jailing of former president Nicolas Sarkozy.

So is Italy really the new France? Not quite. Financial institutions love extreme prudence and that’s precisely what Italy has been pedalling under its far-right prime minister, Giorgia Meloni. Spending has been reined in but little has been done to stimulate growth or investment. Public debt is still higher in Italy (135 per cent of nominal GDP) than in France (113 per cent) but the latter is catching up. While Meloni’s retrograde social policies have managed to avoid too much global scrutiny, you have to take your hat off to her for keeping together a ruling coalition in a country that doesn’t normally do political compromise.

Beyond politics, Italy has been either cheeky or canny – depending on how you look at it – in stimulating its economy by tempting the wealthy to transfer their fiscal residency here. France’s then prime minister, François Bayrou, even accused it of “fiscal dumping”, in a reference to an Italian flat tax on foreign income and other favourable conditions that have caused an exodus from France, the UK and elsewhere.

Italy has problems that aren’t going away, though, from an ageing population and a Eurozone debt mountain to stagnating wages. But it’s having a good old gloat about arguably being the most stable western European power. Meloni has championed herself as a bridge between Europe and the US, and even Africa. The longer she keeps the government together, the more plausible this will start to sound.

Ed Stocker is Monocle’s Milan-based Europe editor at large.

How Moniepoint opened the door to digital banking for Nigerian citizens

In Africa’s fast‑evolving fintech landscape, few stories embody ambition and resilience like that of Moniepoint. Formerly known as TeamApt, the Nigerian start‑up has, in less than a decade, morphed from a modest provider of banking software into one of the continent’s most powerful platforms.

In October it announced that it had raised a further $90m (€77m) in funding, bringing its total war chest to more than $200m (€172m). The most recent injection includes cash from Google’s Africa Investment Fund and Visa; the calibre of backers signals not only investor confidence but also recognition of Africa’s growing influence in the global digital economy.

Founded in 2015 by Tosin Eniolorunda and Felix Ike, Moniepoint began as a small operation providing software to Nigerian banks. The founders soon realised that there was a deeper problem: millions of Nigerians remained locked out of the financial system, trapped in a hard‑to-monitor cash economy.

In response, they created a network of local agents who could deliver digital services to people overlooked by conventional banks. From remote villages to city markets, Moniepoint’s blue‑and‑white point‑of‑sale terminals became emblems of accessibility. Today the company serves more than 10 million personal and business customers and processes more than $250bn (€215bn) in transactions annually.

The firm’s reputation was cemented during Nigeria’s 2023 cash crisis, when policy shifts and currency shortages brought the formal banking system to its knees. While ATMs went dark and queues snaked around banks, Moniepoint’s agents kept cash flowing and digital transactions alive.

As Moniepoint scales, can it balance rapid growth with its founding mission of accessibility? Its trajectory – joining other Nigerian “unicorns” valued at more than $1bn (€860m), such as Interswitch and Andela – certainly suggests so.

moniepoint.com

Comment:

Cryptocurrencies hog the headlines but it’s important to remember that much of the world still needs a reliable retail banking system.

How Toronto is leading the way in the sustainable regeneration of industrial waterfronts

The regeneration of Toronto’s former industrial harbour is a lesson in sustainable development that many portside cities can learn from. Following decades of planning, the waterfront is in the midst of a major renovation. Jutting into Lake Ontario on the east side of the city, a bleak, 240‑hectare area that was previously home to refineries, coal facilities and shipping infrastructure will soon feature a park, an art trail and modern, affordable housing for 15,000 people.

At the centre of this project is the “renaturalisation” of the Don Valley River, the mouth of which was given an unnatural 90‑degree bend in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to accommodate an industrial port district. This intervention created a risk of catastrophic flooding during major storms until a bid for Toronto to host the 2008 Summer Olympics finally nudged authorities from all levels of government to form a plan to make it accessible and liveable for Torontonians.

“The project doesn’t just unlock the land, it reimagines this whole quadrant too,” says Chris Glaisek, Waterfront Toronto’s chief planning and design officer, who has been working on it for two decades. The first phase was unveiled in July 2025 with the opening of Biidaasige Park, named in the local Indigenous language.

The park is dissected by the new river mouth, which was extended by more than 1km using cranes and cleaned on‑site soil, and allowed to snake naturally. Kayakers paddle in the now‑clean water, while families walk along the shore path. The Lassonde Art Trail is a big draw for visitors, featuring open‑air contemporary pieces embedded into the park. The only theme connecting them is the artist’s inspiration from the landscape.

As the surrounding wetlands slowly regenerate, design work is under way for the nearby community and housing development, with the first residents expected by 2031; it is named Ookwemin Minising, after the cherry trees that once grew here. “We have changed our relationship to the Don River and the city,” says Glaisek. “I hope that this will be a model for more positive development in Toronto.” Other cities that are struggling with housing issues should also take note and make more of their overlooked industrial port areas in 2026.

Comment:

From London and Los Angeles to Singapore and Sydney, port cities are struggling for space – and overlooked former industrial areas might hold the answer. Toronto’s waterfront offers a glimpse of how to do it responsibly, sustainably and in style.

23 well-designed gifts to give the interiors-obsessive in your life

Our line-up of tasteful treats will help to make this festive season one to remember.

1.VASTA CANDLE by Tekla;

2. BUDDY WINE STOPPERS by Klas Ernflo for BD Barcelona from Aram;

3. DARUMA SAKE CUPS from Hinoki Japanese Pantry;

4. PERDUE LAMP by Riccardo Marcuzzo for Lumina from Aram;

5. BALSAM INCENSE BURNER by Paine

6. LIGHT TOUCH RECORD PLAYER by John Tree and Neal Feay

7. TORUS LAMP by The Conran Shop;

8. DIARY SET by Mark + Fold

9. KOPPEL PITCHER 03 by Georg Jensen;

10. ORIGIN COLLECTION by Laguna-B;

11. INARI-KOMA FIGURINE from Japan House

12. FLAT WHITE CUPS by Andrea Roman;

13. KBG SELECT by Moccamaster from Climpson & Sons

14. BOWLS by Grace McCarthy;

15. KO KILN TEAPOT by Kitchen Provisions;

16. EARTHENWARE POT by Kayunabe from Japan House;

17. KO KILN TEACUPS by Kitchen Provisions;

18. SYLVESTRINA TABLE LAMP by Santa & Cole

19. TAIYAKI FISH-SHAPED PANCAKE MAKER by Ikenaga Iron Works;

20. HOMEAWAY STAINLESS-STEEL TABLEWARE by Rains;

21. BOXED FLIP CLOCK by Karlsson

22. CONNECT 4 by Poltrona Frau;

23. EAMES ELEPHANT by Vitra from Aram

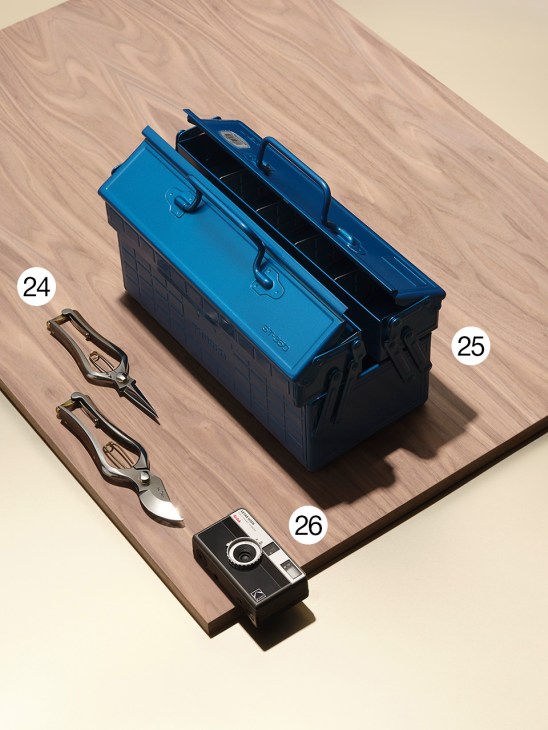

24. KURUMI WALNUT-HANDLE SECATEURS by Niwaki;

25. WORK BOX by Trusco from Labour & Wait;

26. EKTAR H35N HALF FRAME by Kodak

27. CANDLE HOLDERS by Muuto;

28. ARCS SALT AND PEPPER GRINDERS by Muller van Severen for Hay;

29. 7TUBI VASE by Gio Ponti for Molteni&C;

30. ICE-CREAM SCOOP CUP by Miriam Mirri and AAVV for Alessi;

31. BIG LOVE ICE-CREAM SPOONS by Miriam Mirri and AAVV for Alessi;

32. KOKI ICE-CREAM SCOOP by Valerio Sommella for Alessi

Monocle’s guide to three must-try classic Paris bistros

1.

Le Square Trousseau

The neighbourhood favourite

In the 12th arrondissement, near Aligre market, Le Square Trousseau feels at once breezily modern but in ways pleasantly unchanged since its opening in 1907. There’s a belle époque elegance to the bevelled glass, marble mosaics and Thonet chairs, while the menu features classics such as escalope de veau à la crème, steak tartare and crêpes Suzette, plus twists such as the toothsome miso-sesame salmon.

Overseen by Mickael and Laurence Jarno and chef Didier Coly, the restaurant’s reliability runs from the genial staff to the opening times: 08.00 to midnight every day. It’s also a place for all ages, where warmer days see children drawing in chalk (provided) on the pavement outside. The charming, hand-drawn pooch logo on the menu hints at a playful side that belies the effort that goes into the service here.

“I have now been in the kitchen for 40 years,” says Coly. “I started at age 16 as an apprentice in Corrèze and have been working with Le Square’s team for more than 15 years.” Coly’s recipe for success is simple. “It’s a very pretty, authentic bistro,” he says. “[We offer] homemade cuisine with a touch of modernity.”

1 Rue Antoine Vollon

Why it works

The mood at Le Square Trousseau changes with the seasons. In summer, the playground opposite rings with children’s laughter, while in winter, there is a retreat into the cosy interiors. It’s also different across the day, says chef Coly. “At lunchtime, the service is lively, attracting a loyal neighbourhood clientele,” he says. “In the evening, the atmosphere becomes cosy, with candles on every table.”

2.

Chez Georges

The cheerful host

A few steps from Place des Victoires, Chez Georges is the kind of bistro that reminds you why Paris will always be Paris. Run by the charming Jean-Gabriel de Bueil – a veteran of the city’s dining scene and a true guardian of bourgeois cuisine – this address is now his sole focus, and it shows.

The tone is set by the violet-ink menu, leather banquettes, white tablecloths, a pewter bar and large mirrors. The menu celebrates the great tradition of French home cooking, albeit at a standard seldom achieved by amateur cooks. Expect goose rillettes, parsley ham, veal liver with bacon, grilled sole and the beloved pavé du mail – peppery steak with a cognac-laced cream, plus fries.

The puddings are pure nostalgia: vanilla millefeuille, tarte Tatin with thick cream, profiteroles dripping in warm chocolate and a proper rum baba (there are many pale comparisons in Paris). The wine list leans towards burgundy and beaujolais, including De Bueil’s own Chénas Rouge Caillou. Unpretentious, warm and joyfully noisy, Chez Georges is a bastion in a changing city. It’s a type of restaurant of which few remain but those that do remind you of what it means to be Parisian.

1 Rue du Mail

Why it works

Paris is all about personality and Jean-Gabriel de Bueil provides that in abundance. “For my part, the only thing I try to do – with all humility – is to take things seriously without taking myself too seriously,” he tells Monocle. “And to stay true and in tune with the place, its history, its neighbourhood, its guests and the team.”

3.

La Poule au Pot

The nostalgic one

“Everything is guided by sharing,” chef Jean-François Piège tells Monocle, while welcoming us in under the burgundy awning of his beloved bistro. “The dish is placed in the middle, and everyone helps themselves – and then goes back for more.” At La Poule au Pot, sharing plates aren’t a new thing, nor presented as such. Instead, it’s an idea as old as the restaurant, which dates from 1935 and sits in the neighbourhood of Les Halles, long known, thanks to its market, as the city’s “belly”.

Piège took ownership of the restaurant with his wife, Élodie, in 2018 and the pair have sought to update rather than rewrite the rules of a remarkable institution that’s had only three owners in more than 90 years of service. The decor, which includes a zinc counter, mosaic floors and even the original wallpaper – plus unmistakable pink tablecloths and a painstakingly sourced collection of about 2,500 pieces of silverware – is almost as delicious as the food.

“The luxury here doesn’t lie in the drapes or the materials but in the time that we take to cook well and to bring pleasure to those who sit at our table,” says Piège with palpable pride before our French onion soup is served. “I like to say that I didn’t choose La Poule au Pot – it chose me. Élodie and I immediately knew that it was the perfect stage to express my deep love for French cuisine.”

9 Rue Vauvilliers

Why it works

Paris’s culinary reputation precedes it but it can be surprisingly difficult to tell a well-preserved and excellent old bistro from an OK one (of which there are many). La Poule au Pot has survived the many comings and goings of the restaurant scene through its consistency, the hard work of the staff and that most precious of things: knowing when the recipe doesn’t need changing as much as when it does. Bravo Jean-François, bravo Élodie.

Three Parisian bistros have shared beautiful festive recipes for you to make at home. Tap here to read them all and start noting the ingredients.

Read next: Monocle’s full city guide to Paris