Issues

It’s time to raise soft boys and tough girls: Here’s how Iceland breaks down gender stereotypes

If you had to name a nation that’s home to a network of schools practising strict gender segregation, your answer would probably not be Iceland. The country, which has been ranked first in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index for 16 consecutive years, currently has a female president, prime minister, head bishop and chief of police. But it is also the birthplace of the Hjalli model, an education system that is attempting to break down gender stereotypes among preschoolers by teaching girls to be more “masculine” and boys to be more “feminine”.

Devised by progressive educator Margrét Pála Ólafsdóttir in 1989, Hjalli (“rock” in Icelandic) is based on the theory that children are stunted by being taught in mixed classrooms because social pressures cause them to gravitate towards behaviour commonly coded as either male or female. Today it is estimated that almost 10 per cent of nursery-age Icelandic children are being taught under these principles in 18 Hjalli preschools and primaries.

These schools encourage girls to take more risks, speak confidently and directly, and engage in manual forms of play such as stacking blocks. Boys are taught tenderness by playing with dolls, co-operation by painting each other’s nails and being in touch with their caring sides by, for example, giving each other gentle massages. Hjalli children play with gender-neutral toys and wear unisex uniforms, and are surrounded by bare walls and soft colours. This is all supposed to foster creativity and calm concentration. Ólafsdóttir believes that if you separate the sexes and encourage them to behave in ways that are stereotypically associated with the opposite gender, they will develop into more rounded adults, who will in turn forge a more egalitarian society.

Not everyone in Iceland is sold on using such radical, gender-focused methods on toddlers. Kristín Dýrfjörð, a professor at the University of Akureyri, has said that the curriculum at Hjalli schools has calcified. She has written that their regimented structure and stripped-back environments produce schools that are “clinical”, “without history” and as unyielding as the name “rock” would suggest. Researchers at the University of Iceland also found that while Hjalli educated children were more confident, there was little difference in their academic performance compared with other children. That might be why similar ideas, in vogue across the Nordics in the 1980s, fell out of favour.

The Hjalli approach might have more take-up in Iceland than elsewhere precisely because its citizens are already open to its goal – though the fact that most of the country’s schools are not segregated would suggest that such a model is not required to produce world-leading gender equality. Iceland has pioneered efforts requiring companies to report their gender pay gaps and imposed quotas for female representation on company boards of directors. Could it be that Hjalli is more of a consequence than a cause of this success? There has been a Hjalli outpost in Scotland for several years but it has yet to implement its strict gender segregation. If only Iceland’s constitution were as easily exportable.

Comment

While the rest of the world argues over defining gender, Iceland has achieved world-leading equality on terms that everyone understands.

Umekita Park – Osaka’s newest development proving greenery has a place and purpose in urban environments

The port city of Osaka isn’t known for its green spaces or envelope-pushing urbanism but Umekita Park is a lush exception. Occupying the site of a former freight terminal next to Umeda Station, the city’s last prime development area forms part of a scheme called Grand Green Osaka. The space includes residential and office towers, as well as retail, dining and cultural venues set around a new 45,000 sq m park.

When Monocle visits, the lawn is full of life. Friendly pooches bask in the sun, children splash through a fountain and a family celebration unfolds, complete with a portable stereo (at a socially responsible volume), snacks and even chu-hai cocktails. Nearby, a small crowd gathers around a mobile cart, where everything from folding chairs to skipping ropes and kendama toys can be borrowed free of charge. There are even magnifying glasses available for children (or curious adults) who want to inspect the native Osaka flora and fauna.

The cart, developed by Osaka studio Graf, sums up the considered approach to the park’s design, which extends from small-scale initiatives to projects in vast spaces. Another case in point is a Sanaa-designed pavilion, formed by undulating roofs that stretch 120 metres along the side of the park. A section of this serves as a sheltered event space for concerts and performances.

Across the street is the VS exhibition space, designed by Tadao Ando – part of Umekita Forest, the next phase of the project, scheduled for completion in 2027. These projects might be led by award-winning creators but, thanks to the thoughtful work of Seattle-based firm GGN, there’s a sense that the architecture – like the walkways, furniture and planting – has been seeded into the landscape.

In the surrounding development, park-goers can peruse the wares of fashion labels and sport brands, choose between casual dining and high-end tables or even unwind in an open-air onsen. Yet, in a bustling city in which both space and nature are at a premium, the real appeal comes less from the clever buildings and more from the green spaces and Umekita Park itself.

Comment

In urban environments that aren’t famed for their abundant spots of nature, it’s particularly important to make the most of what there is. That might involve providing fun amenities for a park’s users – but any well-considered patch of greenery will be appreciated by residents. Give them space to make it their own.

Why I’m betting on Bangkok for the future of contemporary art

Bangkok isn’t getting a Sotheby’s or a Christie’s any time soon but perhaps that’s its strength. For anyone who is fed up with the art world’s obsession with sales, auctions and the cavalcade of confusingly named fairs, Bangkok could be a good base for the year to come.

While Thailand’s relatively high customs duties make it tricky to trade artworks, this lack of pressure and international institutions has freed up curators, gallerists and talented artists to pursue their work in their own ways. And a spate of independent new openings tells its own compelling story.

DIB Bangkok, a private museum of the late business magnate and musician Petch Osathanugrah’s stellar collection, opens in December. Many top global art institutions are flying in for a visit and it’ll now take you at least three busy days to get a sense of what’s going on in Thailand, rather than an overnight stay.

“Here, everyone and everything has an experimental spirit,” says Gridthiya Gaweewong, the director of the Jim Thompson Art Center and founder of Project 304, an independent art organisation. “Bangkok has become an exciting place for the arts community not only in Southeast Asia but around the world.” Gaweewong compares today’s buzz to that of the 1990s, when a wave of Thais returned from abroad to set up art spaces – only this time the happenings are far better funded and more visible.

Along with its satellite space on Soi Sukhumvit 26, the main DIB building, which was designed by Los Angeles based Thai architect Kulapat Yantrasast, arrives at a busy time for the city’s cultural scene. The Bangkok Kunsthalle opened in January 2024, while its sister venue, Khao Yai Art Forest, a sculpture park three hours’ drive northeast of the city, unlocked its gates in February 2025.

The coming year is expected to hasten the trend: 2026 will see the addition of Decentral, an art centre based in a former denim factory in the city’s busy Watthana district, with a mission to “challenge assumptions”. “I’m very excited about the future,” says Gaweewong. “I’m very curious.”

James Chambers is Monocle’s Asia editor.

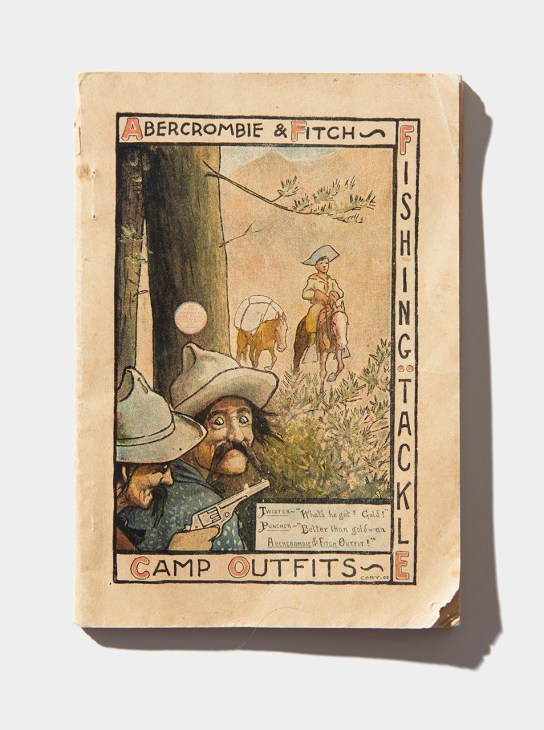

A tour around the Outdoor Recreation Archive, an institution preserving the history of outdoor retail

Visitors flocking to Arctic destinations will spend a pretty penny this winter to bunk down in geodesic domes or glass igloos for a chance to glimpse the northern lights. Others will strap on cross-country skis and snowshoes, while wrapping up in high-performance jackets and trousers to explore the vast frozen landscapes.

The accommodation and equipment required for such leisure pursuits, which are popular today, have their roots in the mid-20th century, when the modern outdoor recreation sector began to take shape. From the 1950s to the 1970s, companies producing outdoor apparel and gear were in their infancy – a cottage-like industry flourishing in garages and workshops.

Innovators included Chouinard Equipment (the precursor to Patagonia) and independent designers such as Charles William (Bill) Moss. The latter began his career at Ford Motor Company and sketched prototypes of car-mounted tents. In 1975 he established Moss Tent Works to make his ideas a reality; his Stargazer II tent has since ended up in the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

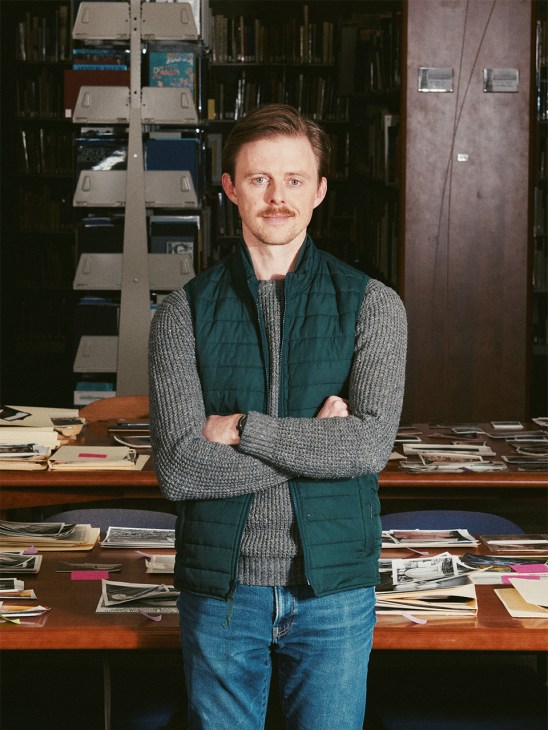

Sketches of this model and the rest of Moss’s papers are among the more than 10,000 items in the Outdoor Recreation Archive – the world’s leading repository of catalogues, sketches, journals, photographs, correspondence and other material related to the outdoor industry. Ideas that were ahead of their time are a common sight in the archive, which is housed at the Utah State University library and intended as a teaching tool for the institution’s Outdoor Product Design and Development programme.

“These early designers envisioned many people participating in the outdoors but some of their ideas failed because they just didn’t have the audience at the time,” Clint Pumphrey, co-creator of the Outdoor Recreation Archive, tells Monocle when we visit, with hundreds of colourful catalogues and sketches arrayed around us on tables. “That’s why we are such an important research resource. Our students will be the ones who will design products and push the industry in the next generation.”

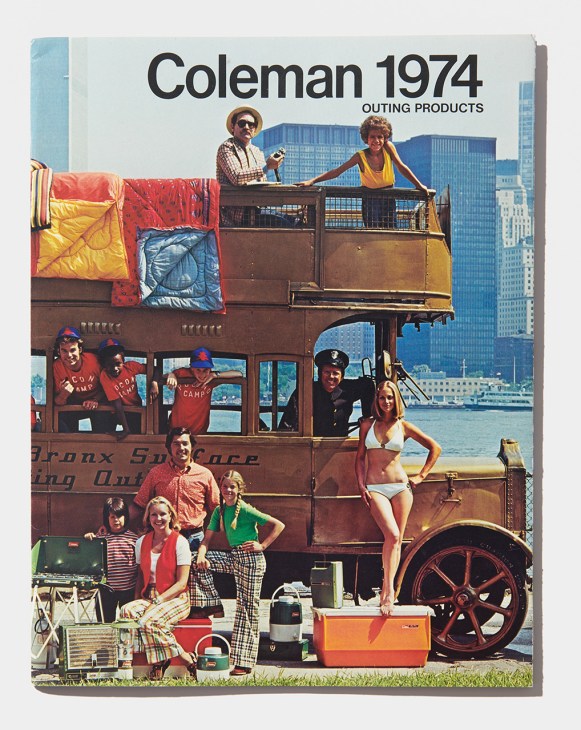

Established in 2017, the archive began as a physical collection of print material before eventually being scanned and transformed into an online material inventory; its popularity, however, boomed when images of its collection were first shared on social media. Highlights include early 1970s photoshoots for US-based company Coleman that look like something out of a Wes Anderson film, attracting a following in cities from London to Los Angeles, Paris to Tokyo.

Soon a global cohort of fashion and design professionals were interested. Avery Trufelman, the host and producer of renowned design-focused radio shows 99% Invisible and Articles of Interest, was among those applying for research fellowships. But the archive’s evolution from an academic pursuit to an international creative resource shouldn’t come as a surprise. In the wake of fashion trends such as “gorpcore” – in which technical or utilitarian gear is worn as everyday streetwear – and the rise of outdoor recreation as a hobby, there’s a growing thirst to better understand the visual and design history of this sector.

Despite this, global cachet is something to which the archive’s co-creator Chase Anderson, the industry relations manager for the outdoor design programme, is still adjusting. “When French customs ask about the purpose of our trip after we’ve flown in from Salt Lake City and our answer is Paris Fashion Week, they’re surprised,” says Anderson, referring to how his team is now invited to events where leading outdoor brands showcase their wares. “That’s not typically what an archivist says when they’re travelling.”

This resonance resulted in a busy 2025 for the team, who released a coffee-table book in June with images from 70 brands represented in the archive’s holdings. In October, it mounted exhibitions at the Westminster Menswear Archive in London and Munich’s Performance Days functional-fabrics fair, in conjunction with Shigeru Kaneko, the chief buyer of Japanese brand Beams Plus. A collector of vintage outdoor garments, Kaneko dedicated a section of his volume Outdoor Expedition Book 99 to the archive after visiting in 2021. “It’s the world’s finest outdoor resource room,” he said at the time, before inviting the archive team to Tokyo to present its work.

The archive’s growing popularity has encouraged more donations at a pivotal moment of reflection for the sector. “This industry is so focused on moving forward, newness, innovation and solving problems that it’s hard to look back,” says Anderson. “But with many of these founders ageing and companies hitting their 50th anniversaries, there’s an opportunity to ask questions such as, ‘What are the origins of this industry?’ and, ‘What made these companies successful?’”

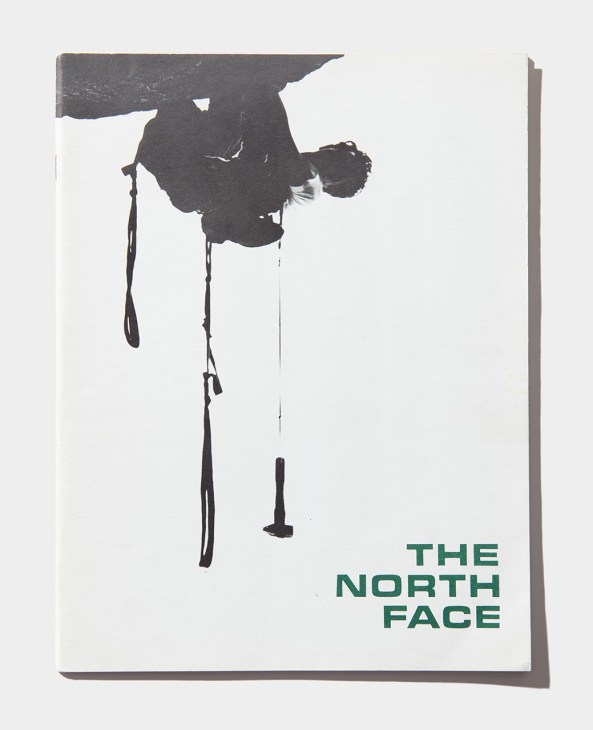

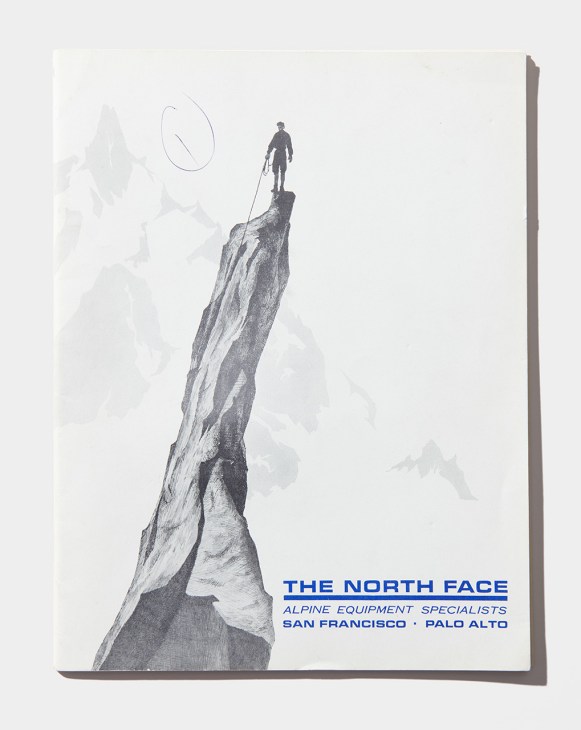

One of the most coveted holdings at the archive covers the early days of The North Face. Founded by climbers in 1966 in San Francisco, the company was sold to Hap Klopp for $50,000 two years later. Typewritten accounting sheets reveal that the company lost money in its early days but Klopp’s business nous and the design acumen of former president Bruce Hamilton helped it to grow from a respected outdoor-equipment maker, while the new owners in the 1990s adopted youth culture to make the brand a high-street staple, with its puffer jackets becoming status symbols. Bought by VF Corporation in 2000, the brand is today valued at $3.7bn (€3.2bn).

The North Face’s chief design officer, Ebru Ercon, is a repeat visitor to the Outdoor Recreation Archive. She was recently here for the fifth time and has taken nearly 70 of her team to browse as part of an onboarding process, helping them to appreciate the challenges the brand faced in its early days. They can also read Hamilton’s letters from architect Buckminster Fuller, who vetted the company’s geodesic-shaped Oval Intention tent (1976), now held in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. It’s a grounding experience for Ercon’s staff. “When you have Hamilton’s sketchbook in your hand, you feel differently about the brand,” she says. “You’re not being given a brief or fulfilling a task. You’re taking a baton from the past and moving forward.”

Ercon treats the archive visit as a structured exercise, asking her team members to reflect on how a certain item inspires them or to compare archival designs with current products. Her approach is similar to that of Utah State outdoor product design assistant professor Mark Larese-Casanova. Archival visits are a requirement for his students when they embark on a new design project and studying old catalogues is a fruitful form of research. Utah State students cut, knit, sew and stitch, and Larese-Casanova believes that the tangible printed matter reinforces the importance of hands-on education.

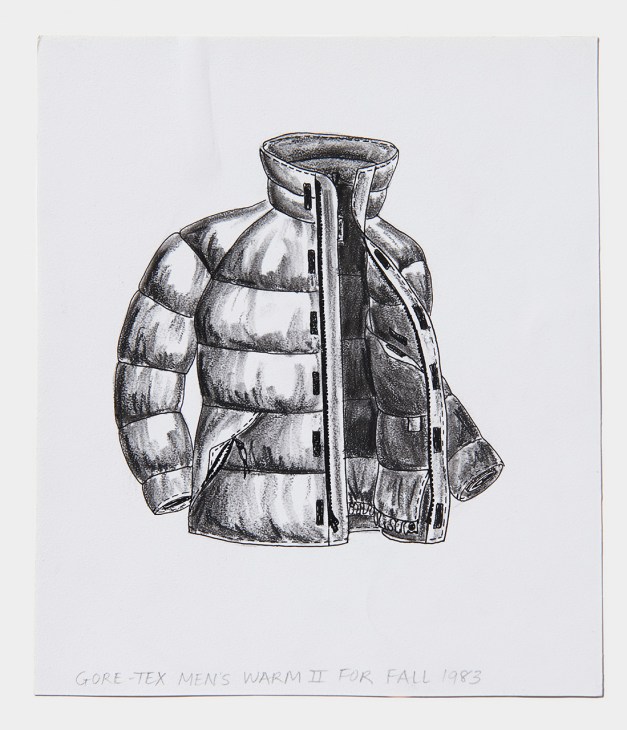

“Having the archive here as a resource helps to enable that style of learning,” he says. Students start the programme sketching on paper before they use styluses and tablets, so the archive is also valuable for overcoming any sense of inadequacy. For all their skills, lauded gear designers were fallible. “There are instances of famous designers, whose materials we have in the archive, where their drawing quality is not very good, which helps the students to overcome the fear of not being great at it,” he says. “Sketching is just about conveying ideas.”

The industry design and fashion talent that dives into the archive makes a point of visiting the classroom as well. On the day of Monocle’s visit, master knifemaker Tim Leatherman is giving a lecture; a few weeks earlier, Hap Klopp stopped by. These practitioners, in turn, are poised to make changes that will ripple throughout lookbooks, across retail displays – and on rugged peaks, with Ercon hinting that some of The North Face’s 2026 collection will draw inspiration from the archive. “There was a bolder and more courageous approach to what was happening in the past,” she says. “That’s what we’re trying to bring back.”

ora.usu.edu

From behind-the-scenes photographs and raw sketches to era-defining posters and eye-opening catalogues, the archive’s collection is a time capsule of materials that spans generations.

In the picture

Among the collection are photos that evoke a family album, capturing many outdoor brands that are now multibillion-dollar enterprises in their infancy. Founders and innovators are shown tinkering in garages or mugging for the camera after a successful outing.

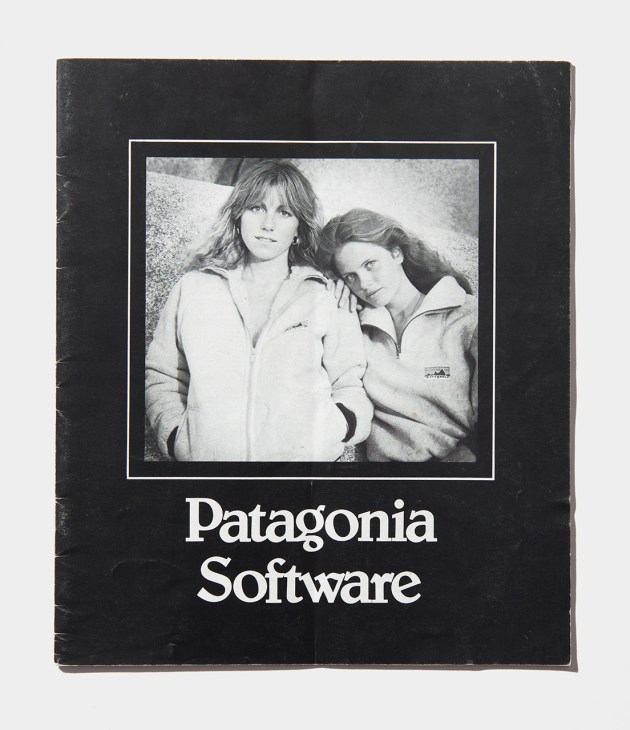

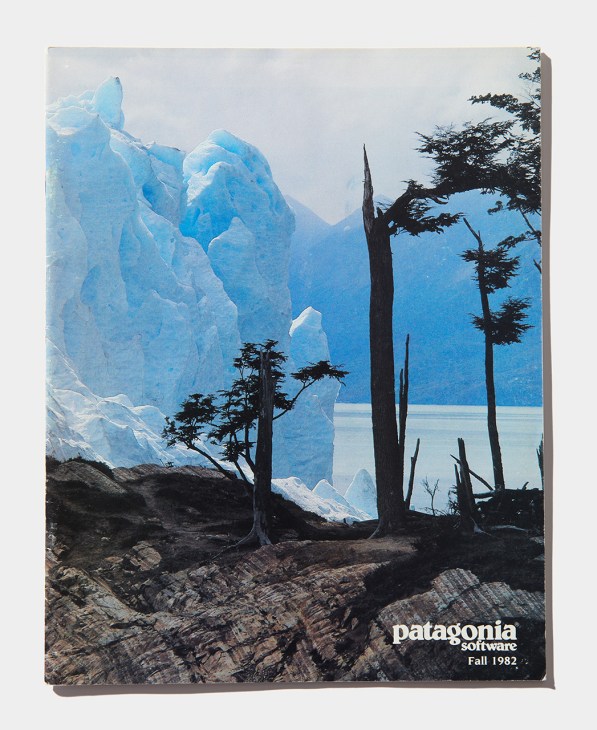

Page turners

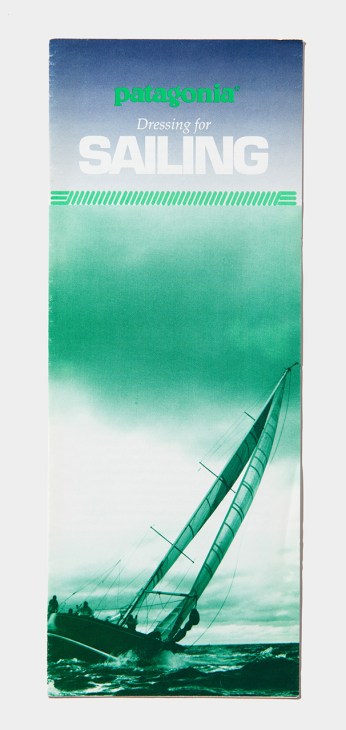

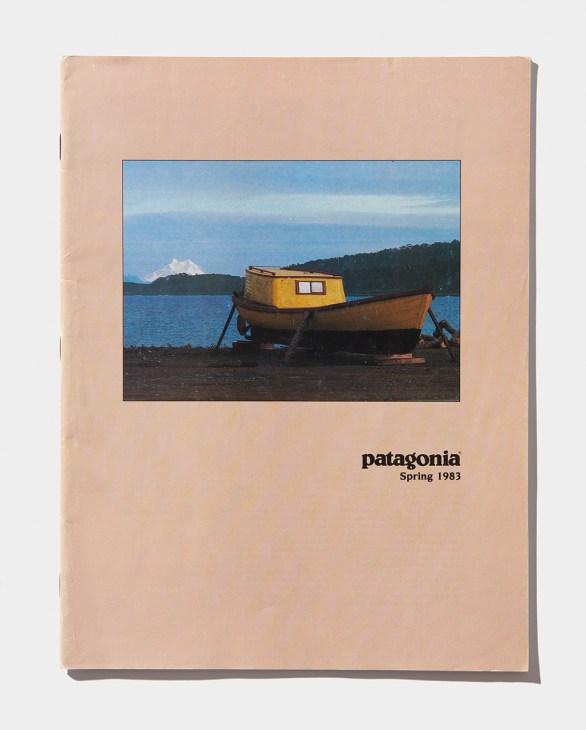

Companies produced annual print catalogues that form a core component of the archive. How brands displayed their products, especially the outlandish and inventive approaches common in the 1970s, can come as a surprise amid today’s more cautious marketing approaches.

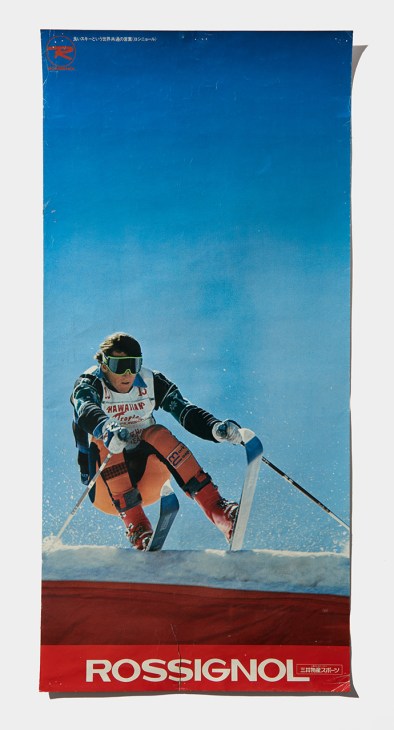

On the wall

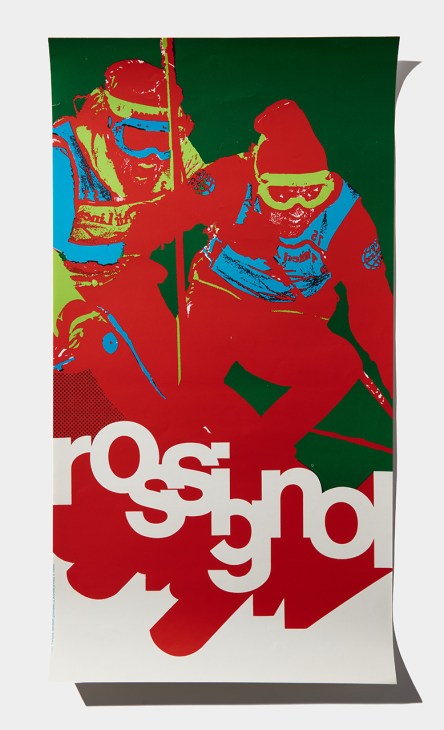

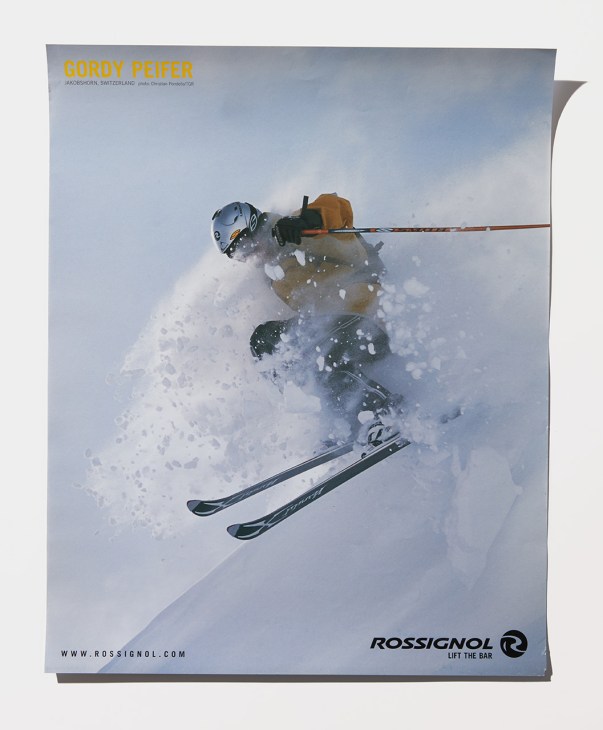

The youthful adventurer’s bedroom or grungy gear shop was not complete without posters. Larger format than catalogues, they depict skiers and climbers in their element.

From mind to paper

The most intimate of the archive’s holdings are sketchbooks from some of the world’s top gear designers, including Bill Moss and The North Face’s Bruce Hamilton. These raw, unfiltered glimpses offer rare insights into their methods.

How a Swiss architecture duo transformed a dilapidated farmhouse into a light-filled, modern home on Lake Geneva

“How we ended up here is a fairy tale,” says Ueli Brauen. The co-founder of Lausanne-based practice Brauen Wälchli Architectes is referring to the home near the small village of Noville that he shares with Doris Wälchli, his partner in business and life. The fairy tale started here at the eastern tip of Lake Geneva in the early 1990s, when the couple had a client whose mother painted landscapes. “I saw one of her works featuring a little house in a field and said, ‘That home has some character,’” says Wälchli. “The woman told us that it was an actual house nearby.”

The architect duo promptly visited the property, finding a dilapidated structure in the middle of a clearing – an 18th-century stone farmhouse combining a barn, stable and living quarters. It had been abandoned for more than four decades. “We contacted the local community, who were the owners and had been leasing it out to farmers. They said that if we were interested, we could have it.” The commune owned a demolition permit for the crumbling building, which had vast cracks in its walls and damaged roof-tie beams (a previous tenant had sawn through them).

Despite this, both parties recognised the significance of the structure, a traditional Savoyard agricultural building with a square floor plan and boxy, mostly windowless façades. “It was once a common typology but now it’s very rare,” says Wälchli. “A lot of farmhouses in the region are abandoned because it’s not easy to receive permits to rezone these houses for purposes other than farming.”

The architects and commune came to an agreement whereby Wälchli and Brauen would have a free lifetime lease on the property on the condition that they rehabilitated the home. “The authorities also listed it as a historic monument, which gave us subsidies from the canton and Swiss governments.”

The successful listing ultimately funded the renovation of a structure that is now a love letter to the region. The duo, while being Swiss-German, felt themselves drawn to the French-speaking cantons in the west, first to study at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology of Lausanne, and then by the lifestyle. “In Bern, where I’m from, we say that the people here drink too much wine and are always late – and we have adapted to that quite well,” says Brauen, laughing, before adding that the landscape is a pull too. The area around Noville is defined by the flat Rhône delta that transforms rapidly into mountains. “There’s no transition between the two landscapes. It means that when you see our home in this low clearing with steep mountains in the background, it’s like a rock, a strong form – a monument.”

The brief that the duo set themselves was to enhance this existing character. “We wanted to give this place its splendour back,” says Brauen. “So we asked the house what it could be.” Its answer? A modern take on the traditional tripartite farmhouse layout. The stable was transformed into a living space, the ground-floor hay barn was reformed as a patio enclosed with sliding glass doors with bedrooms added upstairs, while the original kitchen maintained its function but was given a contemporary overhaul. “We adapted the project to the qualities of the existing building,” says Brauen. “The living room is small and the bedroom large. Normally it’s the other way round but the house wanted the layout to be like this.”

Key structural adjustments were made. The roof was restored with beams straightened and joints repositioned, allowing the exposed structure and rafters to be retained. All the roof tiles were replaced and crumbling walls repaired using rubble found on site. Modern conveniences were added: an insulating mineral render was applied to the walls and new underfloor heating is powered by a heat pump drawing energy from the water table below. Interior elements, except for two masonry walls, were stripped out, inviting light into the open-plan home. Mezzanines functioning as a reading room and study space hover above the ground floor, which includes a double-height living room, defined by a custom four-metre-high bookcase.

“It’s a reference to Pierre Chareau’s bookcase in Maison de Verre, the modernist glass house in Paris,” says Wälchli, who adds that the bespoke work serves a dual purpose. “The glass door for the patio can slide behind the bookcase, opening up the space.” It’s proof of a subtle efficiency now built into the house, with interventions allowing its original atmosphere to remain intact.

A case in point is the lack of windows. Three small openings were inserted in the upstairs sleeping quarters, with the local authority authorising the architects to make additional openings in the roof to bring in more light. They declined. “We said no because of the existing presence of the house,” says Wälchli. “We wanted to keep it as strong as possible.” As a result, they glazed the gaps between the roof and wall structure, which originally ventilated the barn, bringing light to the upper floor without altering the structure. A creamy Jura gravel was also laid around the house and in the patio space, reflecting additional light into the interiors.

Iconic furniture is dotted throughout the home: Le Corbusier armchairs; a small table by Pierre Chareau that sits in front of the bookcase that he inspired; bentwood dining chairs by Josef Hoffmann, a Jean Prouvé table; Eames side tables; Louis Poulsen pendant lights; and simple timber stools to the design of mid-century Swiss carpenter Jacob Müller.

All of this complements custom in-built furniture, including a long daybed sitting in a nook that can be sectioned off by sliding horizontal lamellas. “It’s a reference to the mihrabs of Arabic architecture – Ueli worked in the Middle East,” says Wälchli. “The daybed corner is perfect for coffee on winter mornings when the sun comes through the space. In summer we move out to the patio; we live in the house according to the changing seasons.”

Despite this inbuilt seasonality, the house remains visually connected to itself year-round. “Wherever you are, you can see the whole volume,” says Wälchli “When you’re in the ground-floor kitchen, you can see the top of the roof. It feels generous. There are high spaces and compressed spaces, and there are few windows, but all of the openings have views like paintings.” It’s an appropriate observation, given that a painting first drew Brauen and Wälchli here. Some 30 years on, the duo have transformed the home on that original canvas into a living work of art.

Colom: The new three-storey, multi-brand shop in Palma that’s raising the bar for retail

In the heart of Palma, the doors have just opened on a new multibrand shop for men and women – and it’s one of the braver retail ventures that the city has seen in a long time. Challenged by the impact of tourism, many old-school bakeries and shops here have closed and trinket merchants have replaced them. But in the heart of the Mallorcan capital are a trio of neighbouring businesses that cater for locals and the sort of visitors who want to return home from a city saunter with something more substantial than a fridge magnet.

These are places that are helping to raise the bar when it comes to design, service and the commitment to doing retail well. Monge is a purveyor of Mallorca-made shoes; Relojería Alemana is a luxury watch and jewellery shop; they are now joined by the three-storey Colom, which takes its name from the street where they all sit, Carrer de Colom.

Colom was created by Suso Ramos – the co-founder of another fashion shop in the city, La Principal – his partner in life and work, Liticia Cerqueira, and Pablo Fuster, whose family owns the watch store. “We had been talking about opening a womenswear shop for many years – somewhere with the space to show brands,” says Cerqueira. “Suso and Pablo had lunch one day and Pablo mentioned this vacant property. Suso suggested a pop-up but Pablo said, ‘Let’s do a store.’”

Instead of just offering upscale womenswear, they decided to bring in menswear, luggage and fragrance across the 750 sq m space. To re-engineer the building, the team called on De Prada Arquitectura, whose founder, Carlos de Prada, had designed a house for Ramos and Cerqueira. Here, he inserted a black timber staircase that unites the three floors, employed local furniture-makers (Resmes) and lighting producers (Contain), and commissioned vitrines and benches from island carpenters.

The outcome is a tranquil backdrop to the collections on display. “The architecture cannot eclipse the clothing; it works like a gallery, a space where you can show the clothes,” says De Prada. He stresses that the final design was the product of a close partnership with his clients, who were keen to treat materials with respect and eliminate the use of chemical-heavy paints. “I love this profession, this island, but you need the right clients to help protect it.”

The shop’s spacious, elegant design is important for more than simply customer experience. “At La Principal, we don’t have enough space so we focus on casualwear. But here we can attract more elevated brands and give them the space to be shown well,” says Cerqueira, who is from Paris and has worked for Veja, Maison Margiela and Maison Kitsuné. In addition to Officine Générale, Barena Venezia and By Malene Birger, the shop also sells the Mews Clothing line, founded by La Principal.

Though in its infancy, Colom is already finding an audience, many of whom have a base on the island. “People are coming in and saying, ‘We really needed this,’” says Cerqueira. She is clear, however, that there’s lots of work ahead as they develop a store that’s short on pretension and high on design – a place that shows what the city could be like with fewer trinket shops.

Carrer de Colom 9, Palma

Studio Nicholson’s Nick Wakeman and Aaron Levine launch minimalist menswear capsule

Once you reach a certain level of success, true peers can be hard to find. When Monocle meets Studio Nicholson’s founder and creative director, Nick Wakeman, and American menswear designer Aaron Levine an hour before the launch party for their joint collection, the pair are adamant that they couldn’t have done this with anyone else. “This is not a brand collaboration,” says Wakeman. “We’re co-designing.” Wakeman founded her brand 15 years ago; Levine spent the early part of his career revitalising some of the US’s biggest high-street names, such as Vince and Abercrombie & Fitch, before launching his own label in 2024.

Now, he’s challenging Wakeman to reinterpret Studio Nicholson’s distinct, minimalist aesthetic through a 26-piece co-designed capsule collection. The line includes everything from knitwear to denim shirting and suede jackets, taking cues from vintage and transatlantic references. It even ventures beyond the brand’s signature monochromatic palette. Here, the two designers discuss how they work together and why experience, humility and integrity matter.

How did the collaboration come about?

Nick Wakeman: Studio Nicholson has collaborated with other brands before but I have never worked toe-to-toe with another designer. I wanted something to light a firework in me and, during a management meeting, I suggested bringing in someone to work alongside me. Aaron’s was the only name I put in the pot.

Aaron Levine: We’d spoken online for a few years and finally met a year and a half ago in London for a 15-minute breakfast. It clicked. Since then, we’ve met regularly in Paris or London and begun making something together – I’d been suggesting we should for years.

Did you find common ground from the beginning?

NW: We were already sending each other reference points: films stills, archive imagery, memes of Rod Stewart on a boat. Aaron had this great presence online. I remember seeing him in his garden wearing a terry robe and Charvet slippers and thinking, “This guy doesn’t care – I love that.”

What did the design process of creating your capsule collection look like?

AL: We’d never done this before and I was nervous. I came to London for a week and first thing on Monday morning we headed out to source some vintage pieces for reference. I need to see all the textures and colours together, so I laid out outfits on the floor. It looks chaotic to other people but that’s how it comes to life. Nick got it immediately – we were speaking the same language.

Aaron, you have admitted that you may have been let go from your role at Abercrombie & Fitch for not saying “yes” enough. Why challenge ideas?

AL: I spent about 20 years working in big, publicly traded companies. There are boxes to tick and creativity becomes a pitch. Saying “yes” is easier. With Nick, it’s not about selling an idea. It feels like being in a band again, playing music that you love.

NW: As much as you have brilliant people working for you, they’re not always going to throw you a curve ball; they want to please. He’s not like that. After 30 years in the industry, it’s rare to work with someone the same level as you. Your peers are the ones with a Rolodex of information and the reference points – fashion is intellectual after all. You need that mutual respect to hear those opinions and take the challenges.

What’s the difference between working with highstreet brands and higher-end, more niche labels?

AL: The brands I’ve chosen to work with are global, vertically-integrated retail brands. I don’t sign up to the high street. I let the design teams know that straight away. At Abercrombie, we completely changed its customer demographic – you can do whatever you want to do, as long as you are true to the customer you’re targeting. It doesn’t matter if it’s a mall-based store or luxury label, you have to have integrity.

What have you learnt from working together?

NW: I don’t usually gush about anyone, but I’ve loved having a proper partner. And as much as I talk him down from doing turquoise ribbed sweater, we meet in the middle. I’d never have made the pieces in this collection otherwise.”

AL: I feel like I worked 20 years in this industry to be able to work with Nick. She’s taught me discipline.

A culinary roadtrip through Latvia’s Gauja valley, visiting the best restaurants beyond Riga

Most visitors to Latvia stop in Riga. Every year, more than a million tourists pass through the old town to see its art nouveau façades and dine in its restaurants that now rival those of its Nordic neighbours. But if you’re on the lookout for an experience that’s a little closer to nature, head north into the forests and farmland of the Gauja valley. This is Latvia’s breadbasket, brimming with fruit, fish and game. It’s also where you’ll find new and innovative restaurants that are quietly turning the countryside into a culinary destination.

Riga to Ligatne, 90 minutes by car

Drive north from Riga and, after an hour, you’ll reach the sandstone valley around the town of Sigulda. There are castle ruins on the hillsides as the river wends past pine forests and through meadows. It’s not just beautiful but bountiful too: freshwater pikeperch swim in the lakes and chanterelles nestle beneath trees; strawberries and apples grow fat before the long winters set in.

In the town of Ligatne, once known for its paper mill, pride of place belongs to Pavaru Maja (“chefs’ house”). The restaurant, which has received a Michelin Green Star for its commitment to sustainable cooking, occupies a historic red-brick villa that stood abandoned until Eriks Dreibants and Juris Dukalskis took it over. On a recent afternoon, the pair poured a shot of birch-sap syrup while unwrapping cheese from Soira, a local maker.

“We had a restaurant in Riga but here you can be closer to the farmers,” says Dreibants. “You get to know the people who grow your carrots or make the honey that you use.” Its eight-course set menu changes every few months to reflect the seasons and the team makes the most of the local community: its ceramics, for example, are made by potters in the region. Its plates are fashioned from birch bark and guest chefs regularly grace the kitchen to offer something new.“That keeps us on our toes,” Dukalskis tells Monocle. One week it might be an Icelandic-Lithuanian collaboration, the next an inventive take on those freshly caught perchpike.

Ligatne to Cesis, 30 minutes by car

About 20km further north, you’ll find a medieval castle built by the Livonian Order in the middle of Cesis, the town where chef Maris Jansons moved after two decades in the capital.

Jansons was in charge of Biblioteka No 1, one of Riga’s top dining rooms, but found himself craving a slower pace of life that was more in tune with nature. “Everything was concentrated in Riga – but why not here?” he asks as we tuck into marinated strawberries served with birch-sap ice cream and locally baked rye bread.

In 2017, Jansons opened Kest, a 25-cover restaurant. It has a deliberately muted aesthetic – think white tablecloths, simple glassware and a veranda-like interior – that allows the food to do the talking. Its name means “the other side of the river” in the Livs language; Jansons likes the way that it evokes the Gauja and the ideas and goods that have long flowed along it.

His menus continue this theme, offering venison and berries in the warmer months and dishes such as preserved tomatoes when the mercury falls – though you’ll also find a kabayaki-style cod dish with Japanese mayonnaise on the list.“Quality first, not geography,” says Jansons.

The desserts here, however, lean conspicuously into local specialities. In the summer, there’s a dish that riffs on the traditional honey cake with sour cream and sea buckthorn. Jansons insists on challenging himself with every menu change. “If it doesn’t surprise me, why would customers be surprised?” he asks.

When Jansons started Kest, Cesis wasn’t quite ready for what it served. “In rural areas, people like to cook at home,” he says. “Restaurants weren’t really part of the culture at the time – a result of the Soviet years.”

But curious diners eventually found the restaurant: at first, it was Rigans seeking something different, then tourists and, more recently, local residents looking for somewhere exceptional to celebrate special occasions. Jansons sees the project as cultural as much as culinary. “Food is how we reclaim what was taken during the Soviet occupation. It is art and tradition. It’s what keeps a nation together.”

Cesis to Valmiera, 30 minutes by car

Further north still is Valmiera, a town with a theatre, a booming industrial base and a growing population of younger people moving back from the capital. It also boasts Akustika, a restaurant that has helped to make dining out a part of local life here.

Its founder, Ugis Bormanis, is originally from Riga. Like Kest, it took time for residents to come round to what Akustika offers. “We were more ingredient-driven than people here were used to,” says Bormanis. “At first, they didn’t understand. Now, most of our guests are locals.”

The restaurant seats 70 and is often full at weekends. Duck breast is the bestseller; other favourites include freshwater fish from nearby lakes and beef tartare sourced from an organic ranch. Bormanis likes to keep things simple. “Don’t cover the flavour – you want to taste the beef, not the garnish,” he says.

On the drinks list are lemonades flavoured with quince, meadow flowers and basil, and wines from producers that aren’t stocked by supermarkets in Riga. “We want people to try something that’s new but still feels close to them.”

Our culinary picks

Pavaru Maja

Farm-to-table restaurant amid natural surroundings.

Kest

An ambitious take on Latvian cuisine by one of the country’s best-known chefs.

Akustika

A popular neighbourhood bistro with seasonal dishes.

Straupe Slow Food Market

Farmers sell their fresh produce here on Sundays.

Getting here

First, fly to Riga Airport. It offers direct flights to and from more than 100 destinations so getting here shouldn’t be difficult. Rent a car and stock up on snacks and drinks: this is a two-day trip on pleasant roads that takes you through national parks, beautiful villages and verdant farmland. The best place to stay on this route is the medieval town of Cesis.

Inside Amy Powney x Finisterre’s design-led capsule wardrobe for your outdoor adventures

Amy Powney began her career “sweeping the floors and working her way up” at Mother of Pearl, the London-based ready-to-wear label founded by Maia Norman. She became the brand’s creative director in 2015 and, for nearly a decade, worked to modernise the its business model by moving away from runway shows, offering seasonless designs and investing in natural, environmentally friendly materials. Her impact has been felt across the fashion industry – she has helped to educate consumers to make better shopping choices and held her peers to higher standards.

At the start of 2025 she decided to go out on her own. She launched Akyn, a women’s ready-to-wear brand, and soon forged a partnership with Cornish label Finisterre, known for its specialist outdoor wear. “I just turned 40 and felt it was the right time to go my own way,” says Powney. “The world has changed so much, I wanted to say something different.”

Building a sustainable supply chain is key to her strategy, with Akyn producing in small Portuguese factories and using only four fibres: cotton, lyocell, regenerative wool and European linen. “Until the industry finds a viable recycling solution, I don’t want to take part in the fossil-fuel industry, so I limit our fibre pool to natural or regenerative textiles,” she says. “My ultimate vision is to create a product that leaves no trace.”

This time, Powney is thinking more deeply about the creative process. “We lost connection to the craft and the process. When I think back to my time as a student, we were researching the likes of Martin Margiela, Coco Chanel and Alexander McQueen, and so much was about design. If we can emotionally engage people back to the product, we can get them to be less consumption-focused and more swooned by creativity and connection [to the makers].”

Powney is also ensuring that she is surrounded by people who inspire her, appointing an advisory community that includes the Tank magazine CEO, Caroline Issa, and Textile Exchange’s Claire Bergkamp. “I want this to be a community brand,” says Powney. “That’s why I didn’t name it after me. I believe in being part of a network.”

It’s also why she began working with Finisterre at the same time as she was launching Akyn, having found common ground with its founder, Tom Kay. “What you see is what you get with them, there’s so much heart and soul in what they do,” says Powney, who has been visiting Cornwall, in the southwest of England, to design her first collaboration collection with Kay. “As a designer who was so accustomed to working around the clock and never leaving the studio, it was so nice to visit the Finisterre HQ and connect to nature, to a different way of making products. Going for a morning swim is part of their routine.”

The new capsule includes the kind of coldweather essentials in which Finisterre specialises: a waterproof parka in elegant burnt orange; a quilted jacket made of recycled fishing nets; a long coat that can double as a beach robe. There’s also knitwear, from cosy fishermen’s rib jumpers to knitted balaclavas – part of a strategy to expand the brand’s offer to include more urban wear and fashion-focused designs.

“There’s a massive gap in the market for outdoor products that are also design-led,” says Powney. “Urban brands tend to prioritise design, while most outdoor brands purely focus on function. We wanted to create something beautiful, with interesting silhouettes, that still retains all the technical qualities. Our brands are very similar in terms of our ethos, we just produce very different clothing. It was amazing to meet in the middle.”

akyn.com; finisterre.com

How Lisa Yang’s Inner Mongolian cashmere balances rapid growth while staying independent

In her wood-panelled Stockholm headquarters, Lisa Yang pulls out three little bags of undyed, unwoven cashmere yarn – they are as light as air and smooth as butter to touch. “Inner Mongolia produces the world’s best cashmere because the extreme cold causes its cashmere goats to grow exceptionally fine, long and soft undercoats,” she says, as she slowly unravels parts of the woolly clusters. “We always source the best cashmere available. This one is particularly soft, durable and lightweight.”

Having grown up near Inner Mongolia, a northeastern region of China, Yang’s familiarity with the fibre stretches back to her childhood. Her parents were involved in textile production and she would visit factories and cashmere herders as a young girl. When she moved to Stockholm, Yang put this knowledge to good use by launching her eponymous label with her husband, Samuel Stenberg, in 2014. The result is one of the fastest-growing cashmere specialist brands in the luxury market.

“We had this shared dream to build a perfect business,” says Stenberg from the office that he shares with Yang. The couple are dressed in cashmere sets from their own collections (grey trousers and a voluminous black cardigan for her and a fuzzy argyle jumper for him) and we are surrounded by fabric swatches, sketches and inspiration mood boards. “Our three pillars are to be profitable, low-risk and scalable. We started with no external capital, which meant slow growth at the beginning, but word of mouth eventually helped fuel growth.”

The brand, which has remained independent, turned over €20.8m in 2024, with a 900 per cent increase in sales over the past four years. The company is stocked in more than 500 retailers across 45 countries and Stenberg and Yang also hint that a retail shop might be on the cards in the near future.

The construction and quality of the cashmere is part of the duo’s winning formula but the appeal also lies in competitive pricing. Classic cashmere jumpers are priced between €335 and €990, with costs determined by the quality of the fabric rather than marketing or inflation.

“We use the best fibres and try to push the craft, working with the fit, the silhouette, the details and innovation,” says Yang as she moves around the company’s showroom, where knitwear across a soothing palette of butter yellow, dark grey and cream line the rails. “The inspiration for the designs comes from Scandinavia but I wouldn’t call the style minimalist,” she says. “We like colour too much to be considered minimalists.”

lisa-yang.com