Issues

From Trump to Milei, these are the gifts our world leaders desperately need

There was once a time when world leaders would give a pro forma response to the stock interview question, “What do you want for Christmas?” The answer would be something along the lines of “world peace” or “ending hunger”. But the current crop of global potentates includes several people from whom such a reply might be hard to believe. So let’s ponder instead: what should our overlords ask for?

Friedrich Merz, road bike

Germany is racing to modernise its defence industry while also upgrading its creaking infrastructure. Friedrich Merz, a selfprofessed cycling enthusiast, should get out onto the nation’s bridges and roads to test their condition. His bike should be an expensive one – perhaps an Achielle Ernest – so that he’ll take extra care navigating (and noticing) any potholes.

Javier Milei, six-month macroeconomics workshop

Argentina seems locked in a feedback loop: sharp fiscal and monetary policy moves, market sensitivity and fragile macro fundamentals. Javier Milei should be given a voucher for a six-month macroeconomic policy workshop, along with the book This Time Is Different by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff. The book provides a forensic checklist of how crises repeat – lessons that the workshop could develop into concrete steps.

Sanae Takaichi, ‘Billy Elliot’ DVD and golf lessons

Sanae Takaichi is a great admirer of Margaret Thatcher but Japan is not the UK of the 1970s and policies that work in one political culture or time can fracture another. A DVD of Billy Elliot, a film about a young male ballet dancer in northeastern England in the 1980s, should balance her rose-tinted view of the Iron Lady. And because Takaichi is not a golfer, a voucher for some golf lessons should also make it into her stocking. Flexes on the fairway remain door-openers to international deals.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, beekeeping starter kit

Turkey is one of the world’s major exporters of honey but it was recently rocked by scandals over counterfeit products. A beekeeping starter kit would help to address this reality at two levels. The hive would be a hands-on reminder that supply chains and standards aren’t abstract; they are jars on a shelf. Rebuilding capacity often begins with small, visible corrections that signal a different set of priorities – and economies, like beehives, can be delicate things.

Donald Trump, voucher for dinner with four historians

What better than an invitation to an undisclosed location for an evening of fine dining that would bring together leading public intellectuals and historians to discuss the perils of sleepwalking into world wars and the long-term consequences of disrupting global trade? The line-up could include historians Adam Tooze, Christopher Clark, Margaret MacMillan and Jill Lepore. Perhaps Xi Jinping could come along too.

Monocle’s cosy manifesto: 15 Nordic-inspired tips to beat the chill this winter

As the northern hemisphere hunkers down for winter, thoughts have naturally turned to staying cosy. But “cosy” isn’t simply a matter of keeping warm: it’s a state of mind. Soft materials, the use of timber and tonal lighting are all necessary to conjure up the feeling. We guide you through the dark days ahead – and let’s just say that our friends in the Nordics are ahead of the game on all (cold) fronts.

1.

Dodge the draught

Windows can be a bane or a boon when it comes to an evening spent indoors: even the most picturesque old apertures (such as the vast, single-glazed vensters lining Amsterdam’s canals) can quietly ruin the mood as the cold creeps through. Technological solutions, including vacuum-packed glass to keep panes slim, are becoming affordable. But if you’re searching for something able to withstand a Nordic gale, the Danes do it best: from Horsens-based Velfac to Viborg’s Unik Funkis and Glaseksperten in Hjørring.

2.

Go snug

Room size matters. Architects need to create homes with cosy corners and rooms that embrace you. While cavernous open-plan spaces can inspire awe, we all need moments of privacy and refuge (from the day, your children, your work-from-home partner). That bijou home office and book-lined snug are accidental embassies.

3.

Put a cork in it

What if we told you about a material that’s light, simple to install and easy to work with? It also absorbs sound and resists water and fire. It’s renewable, biodegradable and you can even enjoy it with a glass of wine. Cork – the bark of a species of oak tree – might have been embraced too enthusiastically in past decades but it’s time for a comeback. Portugal grows 50 per cent of the world’s supply and firms such as Amorim have helped to get this product into everything from homes and furniture to spacecraft.

4.

Under the hat

Colder temperatures offer the perfect excuse to add a hat to your look – it’s the oldest styling trick in the book and will also keep you warm. Finnish-Greek label Onar Studios makes the cosiest shearling bucket and aviator-style hats. If you prefer a more discreet look – and we don’t blame you – you can’t go wrong with a classic fedora by Mühlbauer, Vienna’s most elegant milliner. onarstudios.com; muehlbauer.at

5.

In the best light

To create a welcoming atmosphere, select lighting in warm tones and position fixtures and lamps below eye level. Keiji Takeuchi’s Poet pendant for Italian brand De Padova sits on the floor, while Catalonian interior design practice Santa & Cole’s Sylvestrina mimics candlelight’s gentle flicker. For an evening wind-down, UK-based firm Ocushield has developed bulbs that block the blue light that disrupts sleep cycles. The key takeaway? Invest in lighting by companies that prioritise softness and warmth.

6.

Cosy people are happier people

Can something as simple as the temperature change how we feel about ourselves and the world? We instinctively connect physical comfort with positivity and there’s a growing body of research that’s, well, warming to the idea too. Peer-reviewed studies have shown that feeling toasty promotes interpersonal warmth (cold people are meaner), while a Swiss study from 2023 confirms that it makes us feel better.

7.

Standard bearers

Passivhaus is one of the best standards for well-insulated homes that require little in the way of energy for heating and cooling. The voluntary German code dates back to the early 1990s, when a four-unit row house was built in Darmstadt-Kranichstein that helped to codify these new standards. In 1996 the Passivhaus Institut was founded in Darmstadt and has been a boon for the crusade for cosiness. But you still need to furnish with soft touches (don’t keep things too functional).

8.

Woolly thinking

When thinking about winter layering, it’s easy to overlook the most important layer of them all: undergarments. Investing in your underwear and opting for natural materials will help to keep your body temperature under control as you move between warm indoor and chillier outdoor spaces – not to mention the added comfort. Heritage label Zimmerli is our go-to for high-quality underwear, crafted in Switzerland from the finest silk, cotton and wool.

zimmerli.com

9.

Great Danes

Copenhagen – the closest thing there is to a socialist utopia on Earth – is pioneering one-for-all, large-scale heating. Using energy from biomass that would otherwise go to waste, the system supplies hot water and warmth to 98 per cent of its residents. The City of Copenhagen works with Denmark’s largest utility company, HOFOR, to provide the water and wastewater treatment.

10.

Pump it up

It’s best to huddle together for warmth – that’s the logic of collective heat-pump solutions. These systems generate heat for multiple residences from a central source. Often taking the form of a communal boiler or heat pump in the basement of a building, they involve pipes circulating hot water into heat radiators or emitters warming rooms and homes. It’s an efficient, lower-cost approach for communities.

11.

Spring into action

Whatever you think of the Romans (if you think about them at all), these tough campaigners knew how to warm up when the lands they conquered got cold and their bodies ached for the warmth of the southern Italian sun. It’s why you’d find them enjoying the geothermal springs of Baden-Baden, Bath or Budapest (and that’s just the Bs). If you’re in the Hungarian capital during a cold snap, the waters at the art nouveau Gellért or the more baroque Széchenyi (both about 40C) remain a wonderful way to warm up.

12.

Full steam ahead

Finnish saunas are less about chatter and more about calm. It’s an age-old ritual of contrasts – hot steam, followed by a quick plunge into cool air. The result is focus, balance and a warmth that lingers. Harvia, the Finnish maker of saunas and heaters, keeps that tradition alive by focusing on natural materials and heaters engineered to give you the perfect löyly – the word that Finns use to describe the hot and restorative feeling that only a sauna can provide.

13.

Two in a bed is warmer than one

Our bodies radiate heat and so it makes sense that your partner can act like a human radiator, especially if you pick wisely – some people are just hotter, temperature-wise, than others. Transference of heat happens best when you’re both only sporting one layer of clothing or nothing at all (now you’re talking!). Scientists also suggest that jumping jacks are good at raising your body’s temperature. Or try some other under-the-duvet manoeuvres… Even if the science is a little shaky, two in a bed is surely more fun.

14.

Or you could just get a hot-water bottle

There’s a certain satisfaction that comes with the nightly ritual of slipping a hot-water bottle under your covers. While the rubber variety has been tried and tested for over a century, new players, such as Dutch company Stoov, offer rechargeable alternatives that harness warming infrared rays. But why add more technology to your life than is necessary? We’ll stick to our boiling water, thank you, and swaddle our bottles in cashmere covers from Johnstons of Elgin.

15.

Dress for the great indoors

A lot of effort goes into finding the puffiest puffer jacket or the perfect waterproof gloves for outdoor adventures – but what about dressing for the great indoors? Perfecting your look for staying in is an art. Start with a well-fitted cashmere set: Begg & Co’s hooded sweaters and knitted trousers are designed with lounging in mind. Finish the look with a pair of shearling slippers from Austrian label Ludwig Reiter and a tall glass of merlot.

beggxco.com; ludwig-reiter.com

Illustrations: Peter Zhao

The best cultural releases from 2025: The most notable films, books and music

As part of our cultural round-up The Wrap, we asked 10 friends of Monocle – from a diplomat to a festival director – to share the best works that they have encountered over the past year.

Joyce Wang

Interior designer

The best thing I watched:

The heartwarming film How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies, directed by Pat Boonnitipat, offers an insight into the nuances of Thai and Chinese culture that I otherwise would not have known about. It’s a serious subject told with humour.

The best thing I read:

I re-read parts of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun this year for inspiration for a project. I love imagining the different spaces from the text.

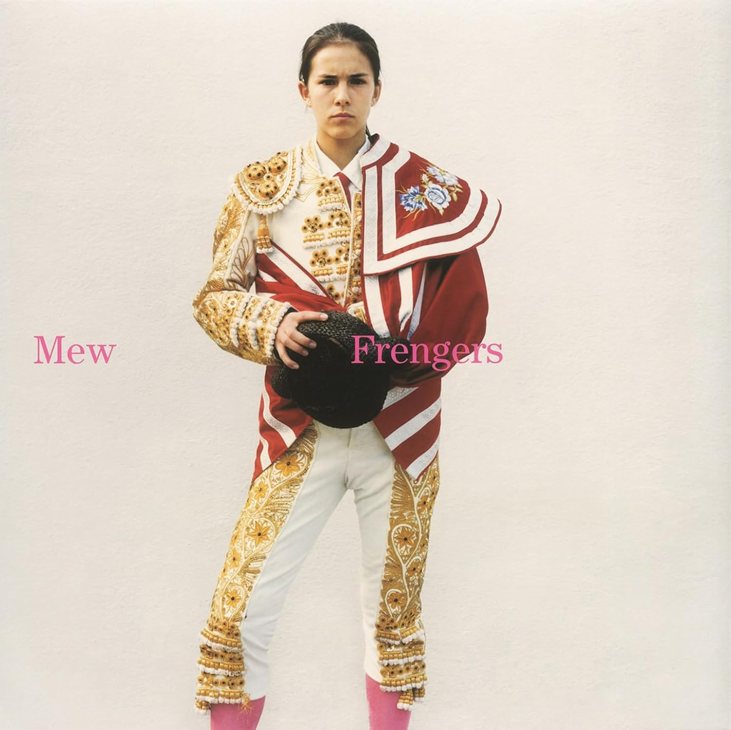

The best thing I listened to:

I’ve loved the Danish band Mew since the early 2000s and they are coming to Hong Kong soon. I first heard them live in Los Angeles.

Wang is an interior designer based in London and Hong Kong.

Tim Weiner

Writer

The best thing I watched:

The Seed of the Sacred Fig, directed by Mohammad Rasoulof, who fled Iran on foot last year after repeated jailings, arrests and harassment. It’s a brilliant movie about repression and resistance in Iran, when “women, life, freedom” was the rallying cry.

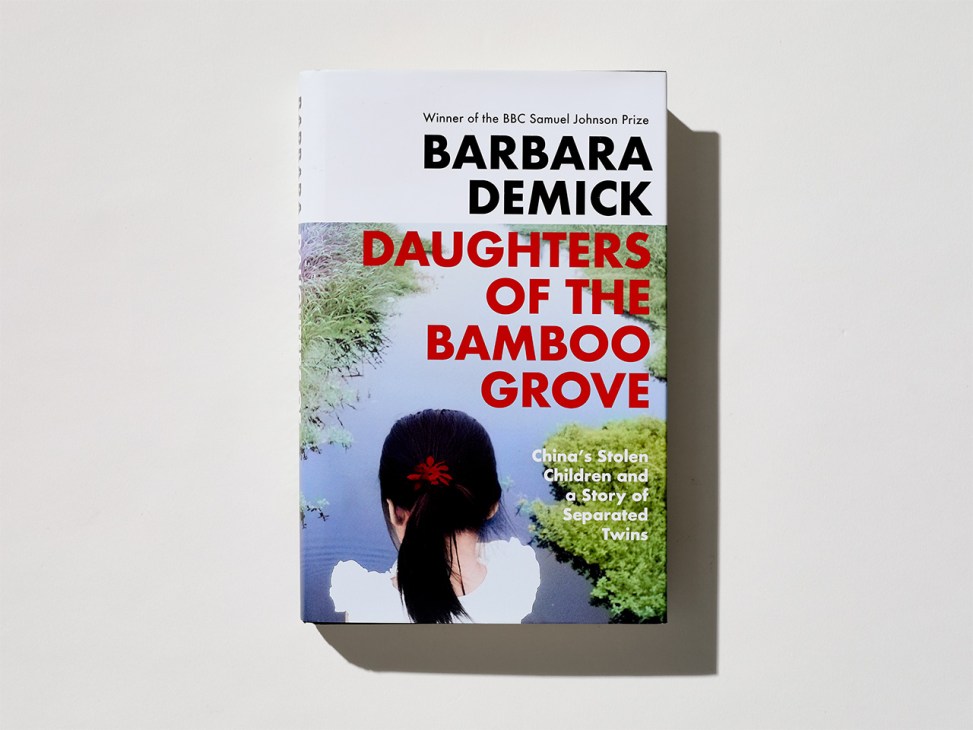

The best thing I read:

Barbara Demick’s Daughters of the Bamboo Grove: China’s Stolen Children and a Story of Separated Twins is an epic of literary non-fiction describing the ripping apart – and the reunion – of sisters born under the one-child policy.

The best thing I listened to:

The song “Breaking” by Anohni and the Johnsons [from the sessions for the album My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross]. Like Édith Piaf, Anohni has a voice that encompasses all the terrible beauty of the world.

Weiner is an American writer and the author of ‘The Mission: The CIA in the 21st Century’.

Antonio Patriota

Diplomat

The best thing I watched:

I loved Kleber Mendonça Filho’s The Secret Agent. It’s a gripping, intelligent film that sheds light on Brazil’s recent past, with cinematic finesse. It’s both thrilling and thought-provoking and illustrates the damage done to society by authoritarian rule and the culture of impunity that it promotes.

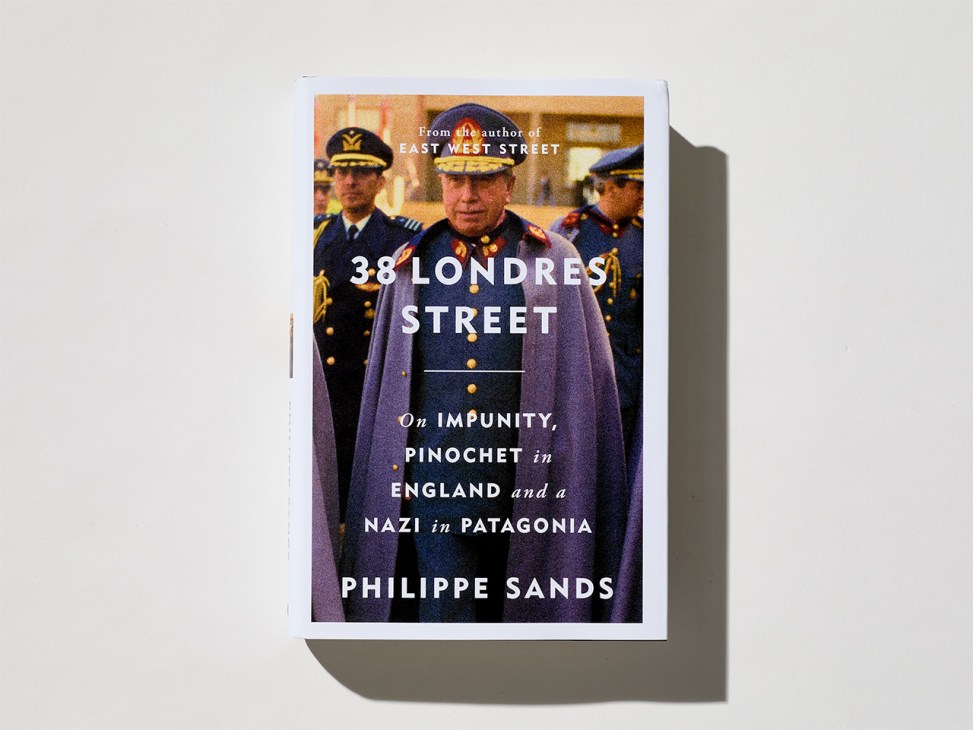

The best thing I read:

Philippe Sands’ 38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England and a Nazi in Patagonia is a masterful blend of personal history and international law. The book is meticulously researched and a groundbreaking testimony of the link between Nazis guilty of war crimes and the torture chambers of the Pinochet regime in Chile.

The best thing I listened to:

Abdullah Miniawy’s album Le Cri du Caire; in particular, the song “Pearls for Orphans”. Miniawy’s voice is just unforgettable. His music is poetry in motion, very spiritual and transcendent. It’s a compelling tribute to child victims of violence.

Patriota is the Brazilian ambassador to the UK.

Nina Conti

Comedian

The best thing I watched:

I was lucky enough to see an early screening of Aneil Karia’s Hamlet. I have never before been able to follow Hamlet’s every feeling so viscerally; it’s such a skilful and realistic performance from Riz Ahmed. A total masterclass in believability from beginning to end.

The best thing I read:

There are passages of Maria Bamford’s audiobook Sure, I’ll Join Your Cult where I had to pull over the car because I couldn’t stop laughing, especially her section on intrusive thoughts. Her worst fears are so dysfunctional, it just makes me glad to be alive.

The best thing I listened to:

This could be anything from Pavarotti to Aphex Twin, but this has caught me on a day when I have listened to “Shoulder Song” by Victor Jones about 20 times. There’s a strength in his voice and an honesty in his lyrics that throw a mighty gut punch. I think he’s going to be huge in no time.

Conti is a British comedian who directs and stars in new film ‘Sunlight’.

Bruna Castro

Writer

The best thing I watched:

Une Langue Universelle [Universal Language], Matthew Rankin’s story set somewhere between Winnipeg and Tehran. I don’t really remember seeing a comedy quite like this before – it’s so quirky and poetic.

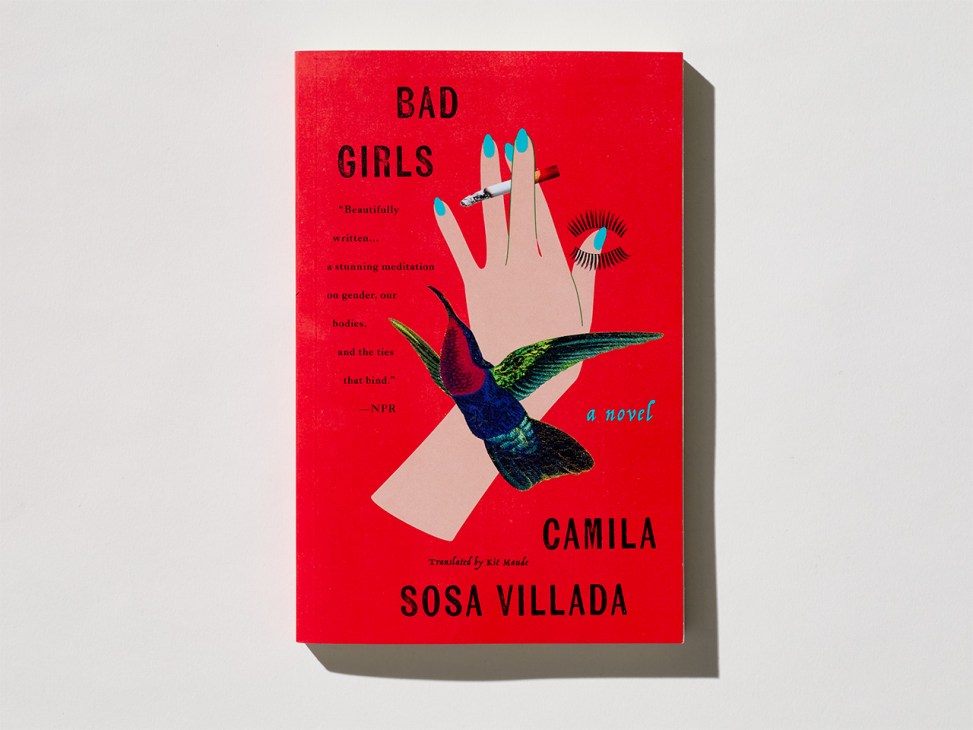

The best thing I read:

Camila Sosa Villada’s novel Las Malas (Bad Girls) is about a trans woman finding community on the margins, written in a style of magical realism. Camila Sosa Villada is a brilliant Argentinian author who deserves to be widely translated.

The best thing I listened to:

Colombian artist Lucrecia Dalt creates experimental music. As someone from Brazil, I know how frustrating it is when people reduce Brazilian music to the same three familiar rhythms. It’s the same with Colombia. I love cumbia but there’s so much more.

Castro is a Brazilian writer and the cofounder of new magazine ‘LatimLove’.

Henry Wilson

Designer

The best thing I watched:

The 2022 documentary Fire of Love tells the love story and work lives of two volcanologists and features incredible, slow visuals and a poignant, tragic end.

The best thing I read:

Simon Winchester’s Exactly: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World is an inspiring account of the history of precision and its profound impact on our lives. I’ve made it essential reading here at the studio. The audiobook is also excellent.

The best thing I listened to:

Alabaster DePlume’s Visit Croatia EP. His music is melodic jazz and we often have this on repeat in the studio and store. There’s a wonderful softness to it; I imagine it’s the kind of music my objects would listen to if they could.

Wilson is a designer based in Sydney and the founder of Studio Henry Wilson.

Robin Givhan

Fashion editor

The best thing I watched:

The Netflix series Adolescence is about a boy from an average, decent family who’s accused of a terrible crime. It’s a gutting story of our times that comes with no clear answers, only profound questions about isolation, virtual relationships and masculinity.

The best thing I read:

Wally Lamb’s The River is Waiting is a novel about forgiveness and what it means to those who receive it and those who are willing to offer it.

The best thing I listened to:

I love the New York Times’ The Interview podcast. Lulu Garcia-Navarro talks at length to people who are famous, powerful or simply interesting. There are no gimmicks. It’s just an exceptionally well-prepared interviewer asking smart questions, listening carefully and being curious rather than judgemental.

Givhan is the author of new book ‘Make it Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture with Virgil Abloh’.

Zaho de Sagazan

Musician

The best thing I watched:

Sean Baker’s The Florida Project, a beautiful film about children living on the margins of society. It’s full of colour and innocence, yet deeply heartbreaking.

The best thing I read:

All About Love by bell hooks made me rediscover what love means: its essence, its depth and its power to transform. It’s a book that questions everything we think we know about love and invites us to live it more consciously.

The best thing I listened to:

All the albums by Italian artist Andrea Laszlo De Simone have been the soundtrack of my year. His latest, released this year, is sublime. There’s something timeless and cinematic in his music that stays with me.

De Sagazan is a French singer-songwriter whose new album, ‘Les Symphonies des Éclairs (Orchestral Odyssey)’, is out now.

Bob van Heur

Festival director

The best thing I watched:

Oliver Laxe’s Sirât isn’t the best movie per se but it’s the most intense and epic movie I have seen. It leaves you stunned, mind-blown and even a bit traumatised. It has the epic proportions of Aguirre, the Wrath of God.

The best thing I read:

In Kalaf Epalanga’s book Whites Can Dance Too, so many of my interests come together: music, the realities of touring musicians, passport inequality, references to my favourite city, Lisbon, and an endless stream of mostly Angolan musical references. It’s told in three parts and has the dynamic energy of a great album.

The best thing I listened to:

Amor de Encava, from the Venezuelan collective Weed420, sounds like nothing else I’ve heard. A collage of sounds mixing Salsa Baúl, noise, reggaeton, encava bus sounds and more. With each listen you discover something new.

Van Heur is the founder and artistic director of Le Guess Who? festival.

Lynne Tillman

Author

The best thing I watched:

In four, hour-long films, Adolescence is a raw, unflinching depiction of a human dilemma and the ethical challenges that nearly break a family.

The best thing I read:

Natalia Ginzburg’s novel Family and Borghesia (translated by Beryl Stockman) portrays the “ordinary” worlds of two families in scrupulous and fierce writing, stripped bare of sentimentalism and melodrama.

The best thing I listened to:

Leon Russell’s “A Song for You”, sung by Russell, Ray Charles and Willie Nelson – the moving lyrics and Ray Charles’ piano-playing “feel” love and death.

Tillman is the author of new book ‘Thrilled to Death: Selected Stories’.

15 brilliant books to gift your friend who has ‘read everything’

1.

Counter Editions

For its 25th anniversary, art-book publisher Counter Editions has released a monograph cataloguing its key works. The design – including a screen-printed cover – mirrors the imprint’s exacting approach to printmaking.

2.

A Room of One’s Own

Virginia Woolf

This centenary edition of Virginia Woolf’s classic essay harks back to the original Hogarth Editions. It’s rebound with the same woodcut prints that her sister designed some 100 years ago.

3.

Mother Mary Comes to Me

Arundhati Roy

In her first memoir, Indian novelist Arundhati Roy describes her formidable mother as “my shelter and my storm”. That complicated relationship forms a central part of the book, told with raw honesty in Roy’s inimitable prose style.

4.

Paul Thek and Peter Hujar: Stay Away from Nothing

Edited by Francis Schichtel

Photographer Peter Hujar and painter and sculptor Paul Thek shared an intimate relationship as friends and lovers. Through photos, postcards, letters and the occasional doodle, Stay Away from Nothing captures the complex and tender nature of their bond.

5.

Nova Scotia House

Charlie Porter

This debut novel from Charlie Porter, the prolific fashion journalist and author of What Artists Wear, is a thought-provoking, emotional work on love and pain during the AIDS crisis.

6.

Shosa: Meditations in Japanese Handwork

Ringo Gomez-Jorge

The Japanese concept of shosa can be summarised as a respectful attitude, a mindful way of moving or a repeated action. This calming book features interviews with craftspeople, teachers and even a high-ranking Zen monk who discuss why shosa is important to them.

7.

Cooking with Scorsese and Others

Hato Press

Cinemas might be more closely associated with mindless consumption of buckets of popcorn than fine dining but food and film have long enjoyed a nourishing relationship. This slim edition features photography that centres on food from films as varied as the Charlie Chaplin classic The Gold Rush and Hayao Miyazaki’s anime Ponyo.

8.

Remixed

Michel Gaubert

Sound designer Michel Gaubert has been responsible for some of the most memorable fashion-show soundtracks of the past 50 years. His new autobiography is for those who appreciate boundary-pushing fashion and music with a little French flair.

9.

How to End a Story: Collected Diaries

Helen Garner

Australian novelist Helen Garner’s diaries were collected into a single volume for the first time this year. Her exacting eye makes this record of the minutiae of her life – including the unravelling of her marriage – a propulsive, generous read.

10.

Squeeze Me: Lemon Recipes & Art

Ruthie Rogers & Ed Ruscha

This unusual cookbook focuses solely on dishes that incorporate the humble lemon. The recipes come from Ruthie Rogers’ London institution The River Café, while the art and design are handled by US artist Ed Ruscha.

11.

Perfection

Vincenzo Latronico

This timely, ennui-laden depiction of an expat couple in Berlin who are attempting to live a perfect life was a literary standout this summer, with its bold, blue Fitzcarraldo Editions cover seen poking out of tote bags on beaches across Europe.

12.

Killing Time

Alan Bennett

This special edition of a new novella from Alan Bennett is the ideal size to slip into a stocking. Though the story – set in a care home during the coronavirus pandemic – is far from cheerful, it’ll be a fine, darkly comic accompaniment for winter nights.

13.

Lessons for Young Artists

David Gentleman

For the creatives in your life, there are few better presents than the no-nonsense words of British artist David Gentleman. While there are no short cuts to success, the 95-year-old’s fatherly advice is sure to help put you on the right track.

14.

Spotlights

Habibi Funk

The musical catalogue of Berlin-based label Habibi Funk Records showcases the best sounds from the Arab world. This smart new publication from the Habibi team continues that mission and features interviews with Arab music legends, retro album designs and new studio photography.

15.

At Home in London

Ellis Woodman

Though London’s mews were built in the 18th and 19th centuries as stables and servants’ lodgings for smart houses, they have since become desirable as bijoux homes and artists’ studios. This book captures their many contemporary functions and varied designs.

Christmas recipes from Parisian bistros Le Square Trousseau, Chez Georges and La Poule au Pot

In an act of seasonal goodwill, a few of our favourite establishments in Paris have shared some usually-under-wraps recipes that will provide your celebratory feasts with a touch of Gallic gourmet gusto.

Le Square Trousseau

Escalopes de veau à la crème

Serves 4

For the cream sauce

Ingredients

- 400g veal trimmings

- 50ml white wine

- 20g carrots, sliced

- 20g onions, sliced

- 20g celery, sliced

- 20g leeks, sliced

- 1 garlic clove

- 2 pinches sea salt

- 1 pinch black pepper

- 4 sprigs of thyme

- 2 bay leaves

- 1.8 litres heavy cream (35 per cent fat)

Method

- Sauté the veal trimmings in a saucepan until lightly browned.

- Deglaze the pan with the white wine, scraping the bottom to dissolve the cooking juices.

- In a separate pan, sauté the vegetables until they begin to soften.

- Combine everything, season with salt and pepper, and add the thyme and bay leaves.

- Pour in heavy cream and simmer gently for an hour, until the sauce thickens and develops a rich flavour.

- Strain if desired; keep warm to serve.

Cocotte de poularde crème et morilles

Serves 2

Ingredients

- 50g dried morel mushrooms

- 50g shallots

- 20g butter

- 50ml port wine

- 50ml madeira wine

- 1 litre heavy cream (35 per cent fat)

- 25g veal stock powder

- 2 pinches of sea salt

- 1 pinch black pepper

- 2 poularde breasts, 400g each

- Puréed mashed potato (for two)

For the morel sauce

Method

- The day before you’re intending to cook, rehydrate the morels in a large bowl of cold water.

- The next day, remove the morels from the soaking water and rinse them several times if necessary to remove any grit.

- Drain and gently press to remove excess water.

- In a saucepan, sauté the shallots in butter until translucent. Add the morels, then deglaze with the port and madeira and let the liquid reduce.

- Add the heavy cream and veal stock powder, season with salt and pepper, and let simmer gently for about 30 minutes, until the sauce thickens to a creamy consistency.

For the poularde

Method

- Preheat oven to 200C. Roast the poularde in a baking tray for 30 minutes with butter, salt and pepper.

- Remove bones while keeping the breast intact. Slice the supreme (breast).

- Plate up the poularde and add the warmed sauce.

- Serve with the mashed-potato purée.

Crêpes Suzette

Makes 10 to 12 crêpes

Ingredients

- 190g plain white flour

- 60g caster sugar, for the batter

- 10g salt

- 1 vanilla bean

- Zest of orange and lemon, to taste

- 4 eggs

- 30g butter, for the batter

- 430ml whole milk

- 180g caster sugar, for the sauce

- 100ml orange juice

- 25g butter, for the sauce

- 20ml Grand Marnier

Method

- In a mixing bowl, combine the flour, sugar, salt, vanilla and the zest of the orange and lemon.

- Gradually add the eggs while stirring, mixing until you obtain a smooth batter.

- Warm up a third of the milk with the butter until it melts completely.

- Once melted, add the rest of the milk and mix well. Pour this mixture into the main batter and stir until fully combined.

- For the best results, blend the batter with a hand mixer to make it perfectly smooth.

- It’s best to prepare the batter the day before and let it rest overnight — it will develop more flavour and yield lighter, more aromatic crêpes.

For the Suzette sauce

Method

- Make a dry caramel: heat the caster sugar in a pan without water to 160C or until it turns a very light brown. Don’t let it darken or burn.

- Deglaze with the orange juice, then add the butter and let it melt gently.

- Zest the orange very finely. Blanch the zest by placing it in a small saucepan with cold water, bringing it to a boil, then draining. Add the zest to the caramel mixture.

- Stir vigorously with the Grand Marnier and cook until the sauce becomes slightly syrupy.

- Warm the crêpes, brush each one with the suzette sauce, and arrange them in a large serving dish.

- Pour the remaining sauce over the crêpes and flambé – carefully – with Grand Marnier before serving.

Chez Georges

Frisée aux lardons

Serves 1

Ingredients

- 1 small frisée lettuce

- 100g artisanal semi-cured farmhouse

- pork belly

- 1 free-range egg

- Aged wine vinegar, to deglaze

- 50g white bread, for the croutons

- Parsley, finely chopped, to garnish

Method

- Cut and wash the frisée in cold water with a few drops of vinegar.

- Slice the pork belly into thick lardons.

- Prepare a vinaigrette with sunflower oil, some aged wine vinegar, Dijon mustard, sea salt and freshly ground black pepper.

- Poach the egg in simmering water with a splash of vinegar for 3 minutes, then stop the cooking in cold water.

- Sauté the lardons in a little oil until golden, then deglaze with a dash of aged wine vinegar.

- Toss the frisée with the vinaigrette, add the warm lardons and top with homemade croutons lightly toasted in the oven.

- Finish with a poached egg on top and a sprinkle of finely chopped parsley.

Pavé du mail

Serves 1

Ingredients

- 220g centre-cut beef fillet

- Freshly ground black pepper, to season

- 30ml cognac

- 100g single cream

- 1tbsp Dijon mustard

- Fresh French fries for serving

- Parsley, finely chopped, to garnish

Method

- Preheat your oven to 100C, then season the beef fillet with salt and freshly ground black pepper. Sear it in a very hot pan for about 2 to 3 minutes on each side (depending on the desired doneness). Keep warm in the oven.

- Deglaze the cooking juices with the cognac over a medium heat.

- Add the cream, stir and let the sauce reduce gently over a low heat.

- Whisk in the Dijon mustard to thicken and bind the sauce.

- Spoon the hot, velvety sauce over the plated beef.

- Serve with freshly made French fries (use yellow-fleshed potatoes such as agria: first fry at 140C to blanch, then again at 180C to crisp and brown).

- Finish with a sprinkle of finely chopped parsley over the pavé.

Crème caramel

Serves 6

Ingredients

- 340g caster sugar

- 250ml water

- 750ml semi-skimmed milk

- 300ml liquid cream

- 5 free-range eggs

- 1 vanilla pod

Method

- Make a light golden caramel by heating 140g of the sugar (to 160C) and water in a copper saucepan.

- Pour the caramel into an ovenproof ceramic terrine dish, swirling to coat the bottom evenly.

- Heat the milk and cream together with the vanilla pod.

- In a separate bowl, whisk the eggs and the rest of the sugar until the mixture turns pale and slightly frothy.

- Gradually pour the hot (but not boiling) milk mixture over the eggs and sugar, stirring continuously.

- Strain, then pour into the terrine dish over the set caramel.

- Bake in a bain-marie in a preheated oven at 140C for an hour.

- Allow to cool completely, then unmould and serve thick slices in shallow bowls, letting the caramel sauce coat each piece.

La Poule au Pot

Gratinée à l’oignon

Serves 4

Ingredients

- 5 brown onions

- 1 knob butter

- Salt, to taste

- 1 sprig thyme

- 1 bay leaf

- 2 garlic cloves

- 250ml dry white wine

- 1.5 litre beef consommé

- 30ml madeira wine

- 20 slices sourdough bread

- 100g comté cheese, grated

- 30g parmesan, grated

Method

- Preheat the oven to 220C. Peel, wash and thinly slice the onions.

- In a saucepan, melt a knob of butter and add the onions. Season with salt, then add the thyme, bay leaf and one crushed garlic clove. Cover and cook gently over a low heat for an hour, stirring occasionally.

- Deglaze with the white wine, then pour in the beef consommé. Add the madeira and raise to a simmer for 10 minutes.

- Toast the slices of sourdough bread and rub them with the remaining garlic clove.

- Fill lion-head soup bowls threequarters full of onion soup. Sprinkle generously with the grated cheeses, then oven grill for about 10 minutes, until bubbling and golden.

- Serve piping hot, with the cheese perfectly gratinéed on top.

Quenelle de bar baignee d’une sauce nantua

Serves 4

Ingredients

- 500g sea bass fillet

- Salt and black pepper

- 200g panade (paste of bread and milk)

- 80g egg whites

- 400g single cream

- 1g cayenne pepper

- 20ml reduced shellfish stock

- 500ml nantua sauce (an enriched béchamel)

- Dash of lemon juice

- Cooked crayfish tails for garnish

Method

- Place the bowl of a food processor in the freezer for 30 minutes. Mince the sea bass using a grinder, then place in the chilled processor bowl with a pinch of salt. Blend at medium speed, then add the panade. Add the egg whites and blend at high speed.

- Gradually pour in the cream while mixing slowly to emulsify the mixture. Season with cayenne pepper and add the reduced shellfish stock. Taste and adjust the seasoning. Transfer the mixture to a bowl set over ice and cover.

- Refrigerate for 12 hours before using.

- Preheat the oven to 210C.

- Using two spoons (or a piping bag), shape the mixture into quenelles and poach them in simmering water for about 5 minutes on each side. Remove and set aside on a baking tray.

- Warm the nantua sauce over a low heat. Add the lemon juice and a grind of black pepper. Taste and adjust the seasoning as needed.

- Just before serving, place the quenelles in a gratin dish and bake for 7 to 8 minutes until puffed and lightly golden. Spoon over the nantua sauce, garnish with crayfish tails and serve immediately.

Île flottante aux pralines

Serves 6 to 8

Ingredients

- Butter, to line baking tin

- 100g caster sugar

- 330g egg whites

- 50g crushed pink pralines

- 500ml custard (crème anglaise)

Method

- Preheat the oven to 140C. Butter and sugar a 20cm baking tin.

- Pour the egg whites into a stand mixer bowl with 10g of sugar.

- Start whisking slowly, then gradually increase the speed and add half of the remaining sugar.

- Whisk at full speed, then add the rest of the sugar. Continue whisking for 1 minute and fold in the crushed pink pralines.

- Pour the mixture into the prepared tin and bake for 15 minutes.

- Once baked, let it cool, then unmould and pour the warm custard around the floating island before serving.

Raise a glass to the year ahead with our 12 best wines of the season

Monocle’s wine expert Chandra Kurt has a useful skill: she can pick a wine for almost any occasion. With the festive season approaching, she shares a selection fit for any special gathering.

1.

The Trouble with Dreams 2021

Sugrue South Downs

British fizz from West Sussex. A blend of chardonnay and pinot noir with a chalky acidity and a fruity expression of Granny Smith apples, gooseberries and lime.

2.

Rosé Réserve Brut 2015

Sekthaus Raumland

This is Germany’s sparkling star. A blend of pinot noir and pinot blanc grapes seduces with freshness, juiciness and delicate fruitiness. A truly great alternative to champagne.

3.

Rosamati 2024

Fattoria Le Pupille

Pure syrah vinified as a rosé from a small plot in Maremma, Tuscany. Delicate, fresh and ideal with lobster or shellfish.

4.

Jaspis Unterirdisch

Weingut Ziereisen

A clay bottle containing one of Germany’s best orange wines – a pure gutedel (called chasselas in France) with enough skin contact to leave a blood-orange hue. Deep, structured and great with roast turkey.

5.

Grattamacco 2022

Grattamacco

The 40th vintage of this Maremma red is ideal for beef wellington or a complex stew. A blend of cabernet sauvignon, merlot and sangiovese with notes of black fruit.

6.

Savigny-lès-Beaune 2023

Domaine Chanterêves

A new-style burgundy by Frenchman Guillaume Bott and Japan-born Tomoko Kuriyama. Hard to get but well worth it.

7.

Arrocal Village 2023

Bodegas Arrocal

The best vintage of this pure tempranillo is marked by delicate tannins and an elegant structure that’s great with red meat.

8.

Cadran Blanc 2012

Château Monestier La Tour

This white bergerac shows a beautiful balance between fruit and structure with a hint of salt. A juicy, refreshing blend of sauvignon blanc, sémillon and muscadelle.

9.

Grüner Veltliner Smaragd 2023

Domäne Wachau

Organic and sustainable, this Grüner veltliner is full of tension and energy, with aromas of ginger and lime. Serve chilled with fish or vegetable dishes.

10.

Château de Vinzel 2024, Grand Cru

Château de Vinzel

Pure chasselas. Notes of honey, white flowers and apple seduce the nose and palate. Great with raclette or fondue.

11.

Cockburn’s 2019 LBV

Cockburn’s

Dense and full-bodied port with fruity notes of black cherries, raisin compôte and blackberries. Perfect with chocolate.

12.

Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey 2022

Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey

This blend of sauvignon blanc and sémillon is a pure nectar that improves sip on sip. A fine partner to foie gras or dessert.

Seafuture is the trade show racing to shape the blue economy with underwater power

Stimulating the so-called “blue economy” might not be a new idea but the geopolitical climate makes understanding, protecting and, yes, monetising ocean resources more important than ever. Indeed, attacks on underwater infrastructure, notably the Nord Stream explosion in September 2022, have upped the ante.

Seafuture, a biennial trade show in La Spezia, a coastal city in Italy’s Liguria region, brings together civilian and military outfits to focus on the great blue yonder. The show’s growth is a testament to the uptick in interest in this field: when the event debuted in 2009, it hosted about 40 companies; at the 2025 edition, it welcomed 370. An estimated 80 per cent of the world’s oceans remains unexplored and there are clearly business opportunities for those navigating and defending the aquatic realm.

“Often the sea is seen as a barrier,” says Cristiana Pagni, the president of Italian Blue Growth. “But we want it to be a bridge that unites.” Pagni’s company organises the conference based on the idea that the sea is not only a means to connect people but a “motor of economic development” that could and should be capitalised on. Given that visiting international naval delegations span countries from Tanzania to Mexico – and the show has attracted brands from India, the US and beyond – she might be on to something.

Defence heavy hitters such as MBDA, Leonardo, Fincantieri and Rheinmetall were all in attendance at the naval base this year. Pagni says that 80 per cent of the companies at the show service both civilian and military markets, with only 10 per cent dedicated solely to defence. Nonetheless, it’s the armed forces that are at the forefront of the blue economy, with their discoveries subsequently bobbing over to the private sector.

“Defence leads the industry in terms of adoption of technology,” says Martijn Wilbrink, business development manager for Europe at Kraken Robotics. Pagni agrees. “Military research results in innovations that are immediately transmitted to civilians,” she says. What’s not in doubt is the rising importance of the blue economy to both businesses and states. And, as host, Italy wants a piece of the action.

The 2025 Seafuture featured a prominent booth for Italy’s newly minted National Pole for the Underwater Dimension, which is based in La Spezia. By bringing together the event but also an ecosystem of SMEs, larger companies and research centres, Italy is seeking to develop underwater technologies and research, and give itself a competitive advantage for the sea change to come.

Three companies floating new ideas at Seafuture

1.

Italy’s Saipem showed off its Innovator 2.0, a remote-controlled submersible craft for oil and gas exploration.

2.

US-based Edgetech exhibited eBoss, which uses sonar for 3D imaging of the seabed. Nick Lawrence, its international business development director, jokes that it’s “an overnight sensation 20 years in the making”.

3.

Canada’s Kraken Robotics demonstrated its Katfish-180, a towbody (an object towed behind a vessel) that can be used for everything from mine detection to critical infrastructure monitoring.

Monocle comment:

As geopolitical tensions and the effects of climate change put the spotlight on the sea, protecting (and policing) it should be on more people’s minds. The year ahead could be, well, sink or swim.

How Europe’s airports must prepare for an increasingly drone-prone 2026

The past year was supposed to be one of soaring growth for Europe’s civil-aviation sector, with a post-pandemic bounce-back and plenty of innovation in sustainable travel, from cleaner fuel to electric flight. Sadly, things have stalled. Among the problems is the debilitating effect of drone activity near airports: as long ago as December 2018, Gatwick, the UK’s second busiest airport, had to close for two days for this reason, affecting more than 140,000 passengers. But the scale of this year’s disruptions in Oslo, Copenhagen and other cities has been on another level, with a spate of incidents lasting several months. It’s a worrying departure from business as usual.

Germany registered a more than 30 per cent increase in air-traffic disruptions caused by drones in 2025, while airports as far south as Spain’s Fuerteventura and Palma de Mallorca have also been targeted. In Poland, news of the national flag carrier Lot’s bid to muscle into the continent’s civil-aviation market was dampened after Russia’s September drone incursion shut down part of the country’s airspace for hours.

Airports and security chiefs are scrambling for solutions and many are pointing to bad actors, including Russia. One short-term suggestion is to empower the police to shoot down drones, something that Germany opted for after its cabinet approved new security legislation in October. Meanwhile, Munich Airport had a laser installed to measure the distance between drones and the airport to better assess the threat. The Danes and Poles have called in Ukrainian soldiers; well-practised in shooting down drones targeting civilian areas, they are now training Danish and Polish soldiers. But there are risks to this approach, from falling drone debris to stray bullets.

Ultimately, the long-term goal must be co-ordinated national air defence and better, less disruptive safety protocols. Beyond the economic impact, a broader problem is that these drones cause fear and uncertainty. Will hopping on a flight feel dangerous if Russia increases its use of hybrid-war tactics? Europe’s connectivity, economy and, yes, even its sense of freedom, relies heavily on civil aviation. Safeguarding it needs to be on the radar for everyone, from airline leaders to politicians and airport bosses.

Three ways to protect airports in 2026

1.

Radars

Used for detection rather than elimination, military radars can help security forces to distinguish between a threat and a wayward toy. Danish armed forces now use such radars at Copenhagen Airport.

2.

Anti-aircraft guns

Germany has snapped up a number of Rheinmetall’s Skyranger anti-aircraft guns, with a repeat order in play. The system can shoot down short-range missiles and cannon shells, as well as drones; for better mobility, it can be mounted on tanks, armoured vehicles or large trucks. But this is a military system for complex threats, rather than a day-to-day solution for the police force.

3.

Interceptor missiles

While most of the drones that we see are relatively flimsy, countries such as the US, Russia and China possess those with a wingspan of more than two metres. Ukrainian engineers have developed interceptor drones to counter the threat. The UK and Ukraine have committed to scaling up production.

Monocle comment:

The West looks naive in the face of hybrid warfare, which seeks – and often succeeds in – destabilisation. Civil aviation needs better protection.

Read next: EOS and DroneShield step up as European drone threats drive global demand for air defence tech

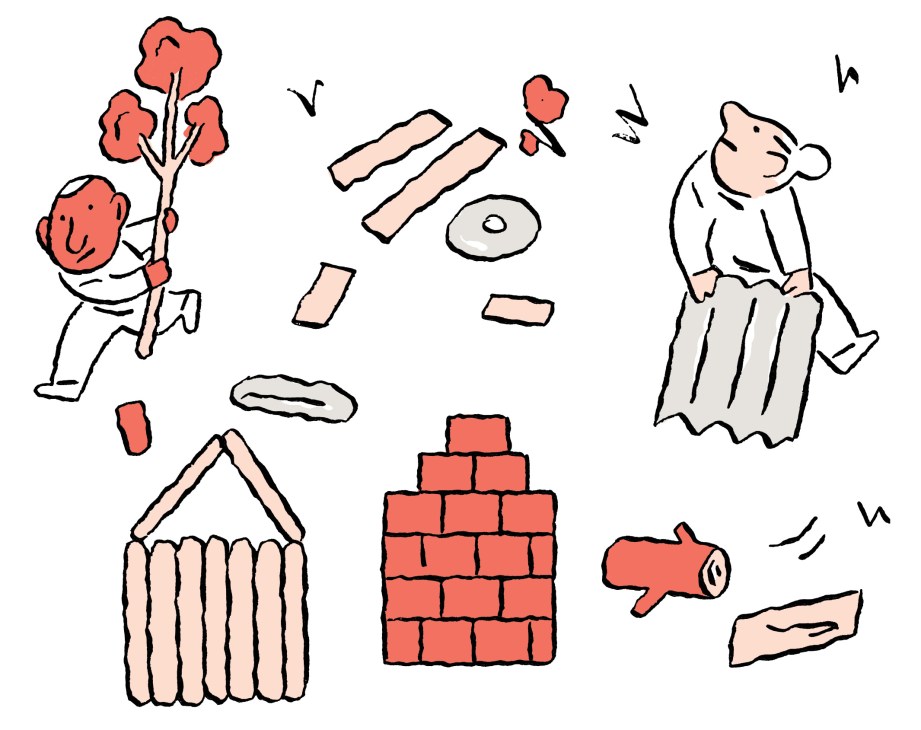

Can the rise of Contech mitigate the US housing crisis?

The US housing crisis has become structural: by some estimates, the country is short of more than five million dwellings, while the price of new homes has climbed by nearly a third in five years. Meanwhile, about 40 per cent of the workforce is expected to retire within the decade, leaving an industry trying to build more with fewer hands and under the growing stress of wildfires, floods and rising temperatures.

Enter “contech” (construction technology). A new generation of firms is using robotics, data and design automation to rethink how we make buildings. Some firms in this sector have already flown too close to the sun: remember Katerra, the Silicon Valley darling that tried to reinvent everything, everywhere, all at once? It raised $2bn (€1.7bn) but collapsed in 2021. Today, others are learning to play smaller and smarter, treating the housing shortage not as a mass-production problem but as one of mass customisation.

In Los Angeles, there’s Model Z, which provides prefab infill homes; in Chicago is the US office of Tel Aviv-based Buildots, which digitally manages construction progress using AI. Another Californian firm, Versatile, uses data about building sites to improve processes. In Massachusetts, you’ll find Reframe Systems, a venture founded by former Amazon roboticists. Its answer to the housing crunch is a network of AI-optimised micro-factories: compact, robotic workshops that can be deployed in under 100 days to produce energy-efficient, healthy and affordable homes suited to a changing climate. Reframe focuses on small homes, duplexes and multi-family residences. Its first micro-factory is in Massachusetts, with the second set to open in Los Angeles in the new year to support post-wildfire rebuilding. “We want to act as co-developers,” says its CEO, Vikas Enti. “We’re working with communities to make resilience accessible, not aspirational.”

Automation, he says, isn’t about displacing labour but augmenting it. The company uses AI-powered work instructions to enable apprentices to perform complex tasks with precision and create accurate floor and roof systems. Just as Enti’s team once helped Amazon to unlock the economics of same-day shipping, Reframe now aims to use robotics to rethink the factory and bend the rules of construction along the way.

Comment:

Advanced construction technology is already helping to build housing both at scale and at speed – but it’s not just a matter of passively waiting for robots to solve all of our problems. Human innovators need to keep finding clever ways to use the tech.

What Osaka’s 2025 Expo taught the world about temporary and sustainable greenery

Temporary greenery is everywhere, draped across shops, trade fair floors or pop-up restaurants. Yet most plants hauled in for the week share the same bleak fate. In Osaka, family-run landscaping company Ryokukou Garden showcased its green-fingered skills to an international audience when Expo 2025 rolled into town.

Responsible for overseeing greenery at the pavilions occupied by the UAE, the EU, Germany, Austria and Panasonic, Ryokukou Garden showed off a simple but effective philosophy that the wasteful trade-show and pop-up circuits should seek to cultivate. Namely it sees plants as living collaborators, not disposable decor, and lets them take root and survive when the trade shows shut.

“We’re not just landscape designers – we grow trees at our own nursery too,” Toshiki Tanisaki, who heads the company’s design work, tells Monocle. “That gives us a real understanding of what plants need to stay healthy.” Now joined by the fifth generation of the Tanisaki family, Ryokukou Garden assures its longevity through continuity. At 89, Toshiki’s grandfather remains involved in everyday maintenance at the nursery while his father manages construction. The three generations handle every stage of any given project, so each decision reflects a shared respect for the plants that they are working with.

At the Expo, the Tanisakis’ brief was simple: to create displays that would thrive throughout the event’s six-month run and be suitable for planting out afterwards. For larger plants, this meant making sure that they didn’t fully take root and could easily be craned out of the event space and replanted while avoiding undue stress. Their roots were wrapped in water-permeable landscaping fabric, preventing them from settling entirely in their temporary home. When choosing smaller plants, Toshiki prioritised perennials for longevity and ensured that they were extracted by hand once the Expo had run its course. “It’s very labour-intensive work,” he says. “You have to dig around very slowly and carefully so as not to disturb the roots.”

While Toshiki acknowledges that it’s common for healthy plants to be thrown out at the end of such events, Ryokukou Garden turned the process into a closed-loop system, one in which nature was not a prop but a partner. Crucially, he says that when a plant is designated for a temporary event, it doesn’t mean that we should treat it with less care. Instead, it’s an opportunity to plan for renewal – something that designers and architects the world over should consider when picking out greenery for their next event.

Monocle’s tips for a greener 2026

1.

Make a start.

Ryokukou Garden’s closed-loop system is admirable but there needs to be more than just one canny company pushing for temporary displays to be treated like an ongoing concern. Take a leaf from its book (or bush).

2.

Ditch the tree quotas.

Cities are blinded by big numbers and developers rush to plant saplings that offer no shade or cover. Context is everything.

3.

Get shaggy.

Keeping every lawn trimmed and weed-free might make sense at a royal residence but cities should leave spaces to go wild: grassy verges and unused railway lines can be left to develop into green corridors for flora and fauna.

4.

Avoid ‘green walls’.

These features can look appealing in renderings but they demand constant attention, care and cultivation to even stay presentable – which is why they often end up being left to wither.

5.

Go native.

Too many cities fall into the trap of planting what looks nice rather than what will thrive. Cities in the Gulf, for instance, should be looking at salt-loving halophytic plants or ghaf trees, rather than beautiful but thirsty and heat-sensitive species that wouldn’t last a day without the sprinklers.

Comment:

Trade shows are excellent places to get a snapshot of an industry, from arms fairs to design showcases, but they’re often wildly wasteful. Better practice means being thoughtful about a fair’s footprint.