Issues

Forest Home: A mid-century bungalow that was designed with R&R in mind

When the founders and creative directors of Amsterdam-based interior design studio Nicemakers are off duty, you can find them in a residence so remote that locating it feels like a treasure hunt. “Google Maps tends to send you the wrong way,” Dax Roll warns Monocle before we arrive at his sprawling rural retreat in Veluwe, a lush nature reserve in the northeastern tip of the Gelderland province, an hour outside the Dutch capital. But our efforts are richly rewarded: the mid-century bungalow, set among fir trees and fields of heather, is an incentive to put down your phone and let nature guide the way.

“Since we completed The Hoxton in 2014 the phone has been ringing off the hook,” says Roll, while unpacking organic vegetables, fresh loaves and fragrant coriander picked up at a food market in nearby Zwolle. Following the unanticipated success of the studio they founded in 2011, Roll and Joyce Urbanus, his partner, created a house in which they could unwind, called the Forest Home. After they discovered the run-down property, they tapped their interior design and architect friends, and within six months the house had been opened up so that its surroundings were visible from all angles.

The pair has designed a slew of smart hospitality spaces: Amsterdam’s renovated De L’Europe hotel in 2021; a country house in Ardennes in 2022; The Brecon, a revamped ski chalet in the Swiss Alps, completed last year; and De Plesman, a hotel in The Hague in the former KLM headquarters, which opened in March. The pair are now working on their Mediterranean residence in Menorca, a restaurant on a regenerative farm in Tuscany and a project in Abu Dhabi, their first foray into Emirati hospitality.

Designing for hospitality came particularly easy to Roll, who grew up working in restaurants and bars before going into fashion marketing. “I didn’t have experience in interior design like Joyce but I understood the practical requirements of designing a hospitality venue,” he says. “Warm lighting is imperative: designers tend to consider illumination as the last stage of the project but we begin with it and work backwards.” Urbanus agrees: “We want our interiors to feel unforced,” she says. “The best compliment we’ve received is that our designs feel timeless, like they’ve been like that forever.”

Indeed, the Nicemakers duo create each of their spaces with longevity in mind. “A client recently invited us back to the penthouse we designed for them a few years ago and the place looked the same,” says Urbanus. It’s their barometer of success: “If something is well-designed, there should be no need to change it.”

Three of Nicemakers’ recent refurbishments

De Plesman, The Hague (2025)

Originally built in 1939, Nicemakers’ most recent project was conceived in the art deco former headquarters of Dutch airline KLM. Now it’s a meeting point for visitors to the seat of the Dutch government. “The story was already in place,” says Urbanus. “We just had to bring it back to the fore.”

deplesman.com

The Brecon, Adelboden (2024)

This 22-key retreat in the Swiss Alpine village of Adelboden, in the Bernese Oberland and formerly known as Waldhaus (forest house), goes heavy on stone flooring, textured woollen upholstery and leather trims. Its decor has a pared-back palette that allows the eye to wander towards the natural beauty without veering too far from the comforts of a traditional timber-clad Swiss chalet.

thebrecon.com

De L’Europe, Amsterdam (2021)

Nicemakers refreshed this Heineken-owned seventh-century inn on the banks of the river Amstel. “After investigating the building’s illustrious history, we set about collecting one-off pieces from the 1900s,” says Roll. “We like to create collected interiors, so it doesn’t feel like a showroom.” The result is a tasteful redesign of the red-brick building in keeping with the Dutch neoclassical style and executed with aplomb.

deleurope.com

How Bahrain is growing its art and design community

Bahrainis see pearls as the flower of immortality. For thousands of years, divers plunged from dhows – with weights tied to their legs and baskets around their necks – into the waters framing the Gulf archipelago, scouring the seabed for the country’s renowned natural pearls. In the early 1930s the pearl market collapsed (around the time when oil was discovered). But the tradition of bringing to light the beauty of the land remained, and now it’s the country’s artists and architects who are tasked with continuing the search. Though not as flush as some of its more famous, go-big-or-go-home GCC (Gulf Co-operation Council) neighbours, Bahrain’s careful yet decentralised ecosystem of cultural interventions – fostered by the relentless vision of several key local figures – has created a rare paradigm in the region. Here is an art and design community marrying cosmopolitan ambitions with deference to its distinctive regional history as an ancient trading hub.

“Artists here are showcasing work that touches us and represents us,” says Shaikha Latifa bint Abdulrahman Al Khalifa, director of The Art Station. “It is not the Middle East as depicted from the outside. It has to do with our memory, our past and our identity; that is why what’s happening now is so special.” Located in Muharraq, an island across an inlet from Bahrain’s capital, Manama, The Art Station is a six-month-old cultural complex housed in an ivory and sky-blue former shopping mall from the late 1970s. It is one of a clutch of new creative undertakings in Bahrain. It’s part of what Al Khalifa sees as a transformation marked by “a certain kind of authenticity,” she says. “It’s very palpable.” One of the main figures at the forefront of Bahrain’s cultural momentum is The Art Station’s founder, Shaikh Rashid bin Khalifa Al Khalifa, an artist, philanthropist, member of the royal family and a kind of godfather for all things contemporary art in Bahrain.

Al Khalifa was one of the founding members of the Bahrain Arts Society when it was started in the 1980s. Since then, he has exhibited his artwork internationally; his pieces span landscapes through abstractions to brightly coloured aluminium optical art reliefs. He later opened the RAK Art Foundation, which includes among its initiatives his former family home-turned-museum. For him, The Art Station was designed to provide a means for artists to expand and reimagine different versions of their practice. This was something that was “just nonexistent” when he was a young artist here, he says. “Back then, there were only self-taught artists, those who just started their own initiatives, painted local scenes and sold them to some of the few tourists who visited the island at the time.”

Beneath the arched colonnades of The Art Station is a central courtyard shaded by palm trees wrapped in white lights and flanked split-level studios for artists that are subsidised by the organisation. At different stages of their careers, some focus on fine arts, while others explore ancient regional traditions such as basket weaving.

Next to a café that abuts the compound, construction workers are hammering walls, expanding the non-profit’s footprint. In the few months since it opened, The Art Station has hosted workshops and supported international residents, collaborating with institutions, academics and artists from Bahrain, the US and Georgia, all aiming to create a talent pool in a country without a formal art school. “I think what they’re doing today with The Art Station – the tools it’s giving young artists – is so important and it was really missing,” says Anissa Touati, a transnational curator who has worked with a number of institutions, including the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Geneva, and is currently an advisor to the RAK Art Foundation.

Over the bridge in Manama is the lush, gated compound of Al Riwaq Arts Space, one of the city’s earliest non-profits devoted to contemporary art. Founder Bayan Al Barrak Kanoo moved to Bahrain from Baghdad in the mid-1980s. Back then, the business of selling and exhibiting art in the country was more informal – there were a smattering of patrons, pop-ups in hotels and invitations for artists to show their work at international exhibitions. Kanoo started out by selling the work of Iraqi artists in Bahrain. The demand, she says, was insatiable and something clicked. A few years later, she expanded her scope, turned her focus to the nascent Bahraini art scene and started Al Riwaq Art Space. The name means “covered portico”, a design motif in traditional Islamic architecture.

Kanoo’s decision to pursue her ambition to champion art in Bahrain was impeccably timed. A few short years after Al Riwaq opened in 1998, a globalised art world started paying serious attention to the Middle East. The first auction by Christie’s in Dubai took place in 2006; Art Dubai debuted at about the same time and museum outposts including those of the Louvre and Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi were announced.

Since opening Al Riwaq, Kanoo has launched a slate of cultural initiatives – including residency exchanges (which have hosted 40 artists to date), art fairs and festivals that work in tandem with Bahraini businesses. This has created the conditions for much-needed infrastructure. “The target is to always push the boundaries,” she says. “Don’t be scared.”

Kanoo moved into her current location, thick with bougainvillea and towering palm trees, in 2022. The many buildings here reflect the extent of her drive: one houses a co-working space, café, library, concept shop and workshop space; another contains multiple exhibition rooms and offices for staff, including William Wells, founder of Cairo’s storied Townhouse Gallery, who is now responsible for curation and running the educational programme here. Behind the main building and the half-moon shaped lawn is a collection of studio spaces.

On the evening Monocle visits, there is an exhibition of work by Bahraini artist Waheeda Malullah. Encased in frames are photographs of chunks of charcoal brightly painted and laid out in a grid; the effect splits the difference between an architectural mosaic and modernist abstraction. Upstairs, Kanoo has gathered several of her past and current artist residents to discuss how Al Riwaq, together with rising cultural investment across the region – most notably neighbouring Saudi Arabia’s multibillion-dollar push that includes initiatives such as the Misk Art Institute – is creating a dynamic young laboratory for regional talent that can go on to participate in all aspects of the art industry. “The pipeline of artists, researchers, curators and writers –everyone you need for the art world to thrive and survive – is an ecosystem that needs to be created,” says photographer Khurram Salman, who was an artist-resident here last year. “Riwaq is one of the only places that has been pushing the boundary.”

The next morning, on a balmy April day, Yasmin Sharabi, director of the RAK Art Foundation, takes us on a tour of the most ambitious project to date: the Daima Museum of Middle East and North African Art (Daima means continuity in Arabic). When it opens in December, it will be the country’s first contemporary art museum. Behind the towering aluminium doors, bubble-wrapped paintings are stored against white walls that have transformed the former villa into an expansive, ultra-modern gallery. Sharabi sees the museum as a space that will allow a younger generation “to re-envision their future through the arts and to bring Bahraini artists with prolific careers” into the conversation. Bahraini artists, she says, have hitherto been paid little attention but deserve to be included in the wider narrative of Middle Eastern art.

On the museum grounds, the final touches are being put on a pair of Buckminster Fuller-designed geodesic domes covered in shards of clay and sand-coloured stone. The effect is mesmerising, simultaneously futuristic and ancient. The tiling, like the land around it, is poised to absorb the heat here (summer temperatures can exceed 40c and months pass without rain). Once the interior is complete, it will house the Bahrain headquarters of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, along with several cultural accelerator programmes. More wings are in the works, including one devoted to East Asian art. “In my view, there’s nothing better than visiting a museum,” says Rashid Al Khalifa. “If I had my way, I would have more museums per square metre in Bahrain than anywhere else.”

Back in Muharraq, a brutalist concrete canopy floats over the southern tip of The Art Station. Designed in 2019 by Swiss architect Valerio Olgiati, the otherworldly intervention, with its open-air ceilings and cut-out light-wells, was designed to shade a former warehouse that stored timber logs for boats and the ruins of a madbasah, a structure that houses dates ready to be pressed into syrup. It is part of the Pearling Path, a 3.5km Unesco World Heritage Site, designated in 2012, that traces the history of Bahrain’s pearling industry from the centuries-old urban centre to the coastline.

The pathway meanders between some carefully restored traditional Bahraini architecture, interspersed with some arresting contemporary structures and renovations. One such building is the Siyadi Pearl Museum designed by Bahrain-based Dutch architect Anne Holtrop, which is filled with Cartier masterpieces and lustrous cracked-open winged oyster shells. The museum’s rugged walls are covered in silver leaf and the colours will shift with continued exposure to the salinity in the air. “It’s like photography; it’s recording the quality of the environment,” says Holtrop. Outside, light bulbs – designed to look like pearls and perched atop concrete columns flecked with mother-of-pearl – act as cairns for visitors making their way through narrow alleyways. The designs of the 17 public squares that form part of the Pearling Path – some feature pools of water, others semicircular benches surrounded by flame trees – give space for visitors and locals to rest. Meanwhile, ramshackle homes, renovated and open to the public, mindfully expose details of the people who called this quarter home: a medicinal garden and apothecary of a resident doctor; homes of divers and wealthy merchants; and a family’s majlis (meeting room).

Like much of Muharraq’s transformation, the initiative, which was officially opened in February 2024, was helmed by Shaikha Mai bint Mohammed Al Khalifa, a member of the royal family. Over the years, she has held different ministerial positions, was the president of the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities (BACA), opened museums and helped inscribe all three of Bahrain’s Unesco Heritage Sites, including Qal’at al-Bahrain Fort and the Dilmun Burial Mounds.

Today she runs the Shaikh Ebrahim bin Mohammed Al Khalifa Center for Culture and Research, which she founded in 2002. The Center has been responsible for renovating multiple spaces in Muharraq, including some that are part of the Pearling Path, and the House of Architectural Heritage. Designed by Leopold Banchini Architects and Bahrain-based Noura Al Sayeh Holtrop, this concrete cube with moveable glass walls hosts exhibitions and a small library.

“What makes Bahrain really interesting in terms of the cultural development is that it never really happens in a void,” says Al Sayeh Holtrop, who joined the government as head of architectural affairs in 2009. The following year, she co-curated Bahrain’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale and won the coveted Golden Lion award. Later, she assumed the role of director of the Pearling Path. (She met Anne Holtrop during the competition to design the Bahrain pavilion for the Milan Expo in 2015 and the two later married after its opening.) “The end product and the end interest is culture itself, and not culture as a by-product or a means of achieving something else,” she says.

1.

Mai Buhendi, The Art Station’s cultural partnerships and programme manager

2.

Latifa bint Abdulrahman Al Khalifa, Director of The Art Station

3.

Nasim Javid, Contemporary jewellery designer

4.

Amer Bittar, Co-founder of design studio Bittarism

5.

Lolo Bittar, Interior architect and co-founder of Bittarism

6.

Karim Al Janobi, Digital artist at The Art Station

That ethos prioritising cultural integrity over commercial flash has had a marked effect on Ali Ismail Karimi, the 35-year-old Bahraini co-founder of Civil Architecture, a cultural practice with an emphasis on making buildings and writing about them. “For me, the sense is that you don’t have to be a large corporate firm to be doing interesting cultural projects in Bahrain,” he says, sitting in a café overlooking the coastal Qal’at al-Bahrain Fort, a Portuguese-era limestone citadel on the site of the Dilmun empire’s one-time capital. In the coming months, he will move one branch of his practice here into a new government-supported development that is transforming former homes into a café and offices for those working in the creative sector.

In Bahrain, he says, “It’s easy to see how things change, how small interventions here can make a big difference.” As he talks, the tide begins to retreat and horseback riders gallop along the muddy seabed. “It’s almost a maquette of the world.”

A brief history of Bahrain

2200-1750 BCE

Bahrain’s earliest pearls are harvested during the ancient Dilmun period. Pearling will soon become the heart of the economy.

7th century

Under Islamic rule, Bahrain and its pearling industry connects to trade networks in and beyond the Arab world.

1521

The Portuguese capture Bahrain and stay for the next eight decades.

1783

Control of Bahrain falls under Ahmed ibn Muhammad ibn Khalifa.

1861

Bahrain becomes a British protectorate.

1912

Jacques Cartier comes to Bahrain on a hunt for the world’s finest pearls.

1932

Oil is discovered in Bahrain. Around the same time, the pearling industry sees a sharp decline as Japan, at the forefront of the production of cultured pearls, overtakes the market.

1947

For Queen Elizabeth’s wedding, the ruler of Bahrain presents her with

a selection of seven pearls, from which she made her famous Bahrain Pearl

Drop Earrings.

1971

Bahrain declares full independence.

2012

The Pearling Path is inscribed as a Unesco

World Heritage Site.

The art of collecting and why people do it

Artwork in a gallery or a booth of a fair can look very different once you get it home. We meet two collectors in New Delhi and New York to find out what decisions go into the acquisition of pieces and how they live alongside their purchases, from gilded Renoir paintings to sculptures made from car doors and plasterboard. Meanwhile, in Tallinn, we hear from a pop art aficionado about why serious collectors shouldn’t overlook the sometimes misunderstood movement. All offer advice worth heeding, whether you’re a seasoned pro or just starting out.

The home curator

Valeria Napoleone

New York, USA

With its white walls and chevron parquet floors, the entrance hall of Valeria Napoleone’s Park Avenue apartment resembles a gallery. On display in the narrow space are two sculptures, both dating back to the late 1980s. Joan Wallace’s “The Frigidaire Painting (Like a Pariah)” is a refrigerator and video monitor sculpture, while Jessica Stockholder’s “The State of Things” consists of a car door, Sheetrock, wood, cloth and a light. Unlike the sorts of artwork that you might find in other people’s homes, which tend to blend in with their surroundings, these are impossible to ignore.

“Every piece in my collection surprises me,” says Napoleone, who has been buying pieces for the past 30 years. She focuses on the work of female artists and her collection is spread across her homes in London and New York. Some pieces are kept in storage; she periodically rotates the works on display. “When you change the installation, you change your relationship with the room, as well as the balance of the space,” she says.

Born in Italy to parents who furnished their home with antiques, Napoleone has always been fascinated by materiality. “When I started collecting in the mid-1990s I felt so engaged and so attracted to the work of artists who were using alternative materials,” she says, adding that the contemporary-art market has expanded enormously for younger creatives. “Back then, I could buy a major piece for a few thousand dollars,” she says. “Now the entry price is at least 10 times that.”

Napoleone has always bought what she loves. “I don’t look at art as an investment,” she says. “It’s my passion.” Within her otherwise neutral apartment are bold works such as Janet Olivia Henry’s blue and black Lego piece, displayed in a glass box, and Pae White’s Sunshine Chandelier that hangs in the dining room. “I love sculpture because it demands your attention,” she says. “It is not just a piece hanging on the wall. You have to acknowledge its presence.”

One of her top tips for collectors is to ensure that they have the right space to accommodate their treasures. Another is to have patience. “You need to train your eye by looking at different things. Learn what your taste is and buy only what you like.”

The talent spotter

Aparajita Jain

New Delhi, India

“How else do you understand humanity but through art?” asks Aparajita Jain, managing

director of Indian contemporary art gallery Nature Morte. “This room encompasses years of human existence.” She’s referring to the works surrounding us at her palatial New Delhi home. Among them is a gilded Renoir, an Alberto Giacometti sketch, a Picasso, a Degas bust, a mobile by Polish-German artist Alicja Kwade and contemporary art by Indian artists Thukral and Tagra. It’s a lot to take in but Jain says that the collection has helped her to understand herself better.

“I collect people’s ideas and their understanding of life, and hope that engaging with them will expand my horizons,” she says. Jain acquired much of the collection over the past decade but she has been buying pieces since she was 22 years old, encouraged by her grandmother, the matriarch of the Borosil glassware family. While she’s chosen much of the art here, her businessman husband, Gaurav, and, increasingly their daughter, Devashi, have picked recent purchases.

It’s a collector’s eye, she says, that makes her a successful gallerist and many of the artists who her gallery represents are also present in her personal collection. “Sagarika Sundaram’s mind is exceptional,” she says of an artist represented by Nature Morte. “I can’t think like her so I want to possess her work.” Jain’s career has been defined by her desire to promote young artists such as Sundaram. In 2005 she launched Seven Art gallery; in 2012 she started a non-profit that helped to launch Jaipur’s exceptional Sculpture Park. Six years later she created blockchain-based marketplace terrain.art, with the objective of being a bridge between younger South Asian artists and collectors in the West.

In 2025, though, she finds the Indian art market far more exciting. “I’ve been travelling extensively and find the mood in India is opposite to that in the West,” she says. “Western economies could be slipping into recession. In India we have a country that’s finally finding its voice, both in terms of aspirations and the quality of art being produced.” Is it time, then, for foreign galleries to set up shop in the country? “They will come eventually,” she says. “I’m sure of it.”

The pop art connoisseur

Linnar Viik

Tallinn, Estonia

Though Estonia wasn’t at the centre of the pop art movement, which emerged in the 1950s, Tallinn is now home to one of Europe’s largest museums dedicated to the genre. The PoCo Pop & Contemporary Art Museum showcases 340 artworks, including pieces by big hitters such as Roy Lichtenstein, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jeff Koons. Here, its founder, Linnar Viik, tells us about the merits of buying pop art and shares some tips for prospective collectors.

Which are your favourite works in your collection?

My collection is extensive because I focus on the past, present and future of pop art. It includes several noteworthy pieces by famous people including Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst and Banksy but my favourite works are those in which an artist revisits one of their earlier pieces. For example, Estonian artist Raul Meel added new elements to “Singing Tree”, his 1970s “typewriter drawing”.

Do you have any tips for budding collectors who are interested in pop art?

The most important thing is to ensure that your collection makes you happy and speaks to you in some way. You should also have a specific place to display it. Pieces of pop art, like works from any movement, don’t belong in the cellar. I refuse to see art as an asset category that you collect for its monetary value. As a movement, pop art was born of the desire to make art more approachable and democratic. Following that ethos, I don’t think that budding collectors should focus all of their energies on looking for first-edition or limited-edition pieces.

Why should people collect pop art?

It’s so honest and courageous in how it reflects and interprets the world. It’s also an easy way to become an art collector because it’s widely available and affordable. It’s an art movement that speaks to people immediately, making it easier to approach. But the more that you collect, the more you will start to see the hidden layers and the deeper meanings in the artworks.

poco.art

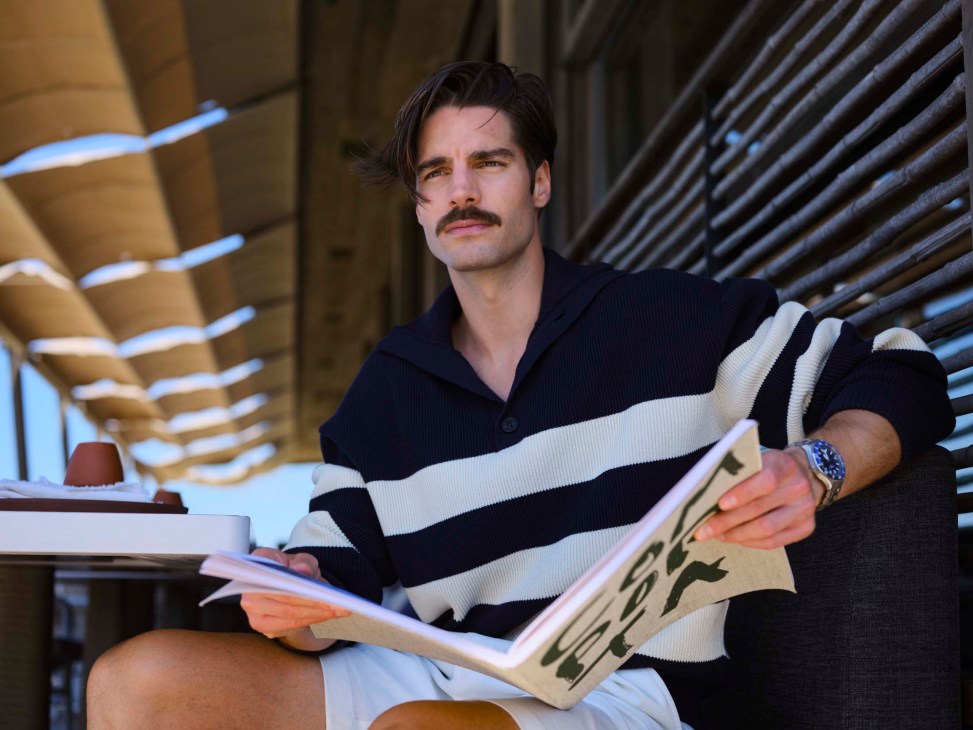

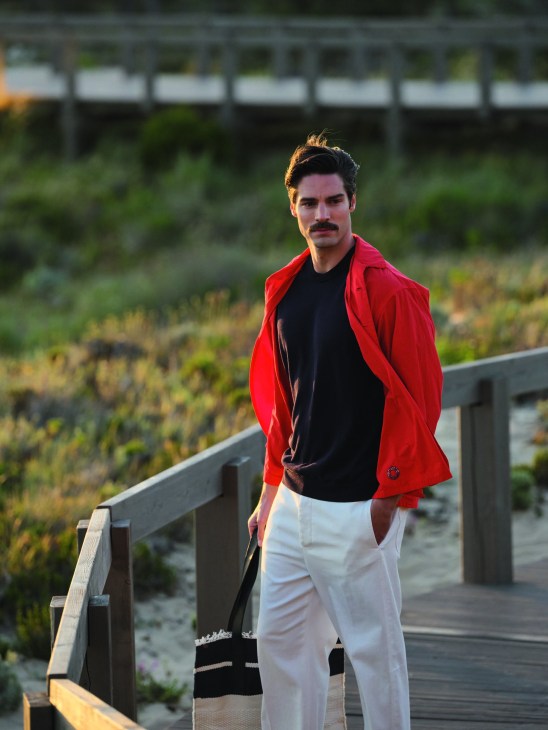

Ready for summer: Wardrobe essentials for the season

Stylist: Kyoko Tamoto

Hair & make-up: Milla De Wet

Model: Kilean Isaak

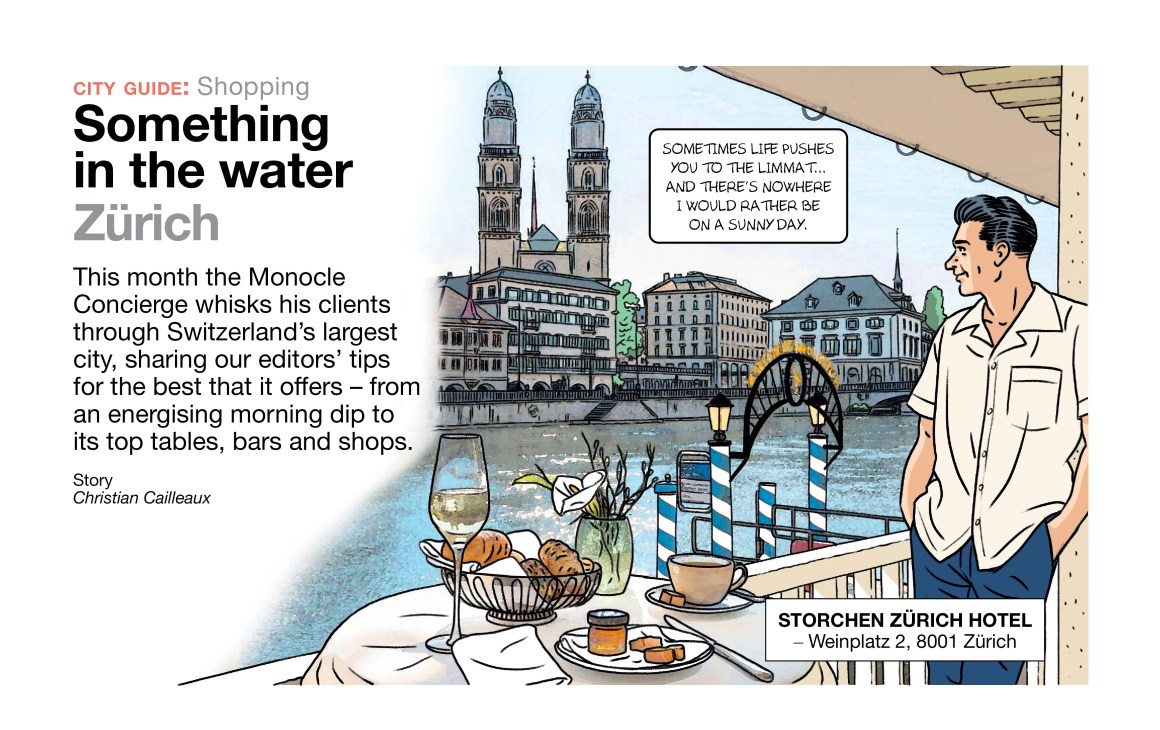

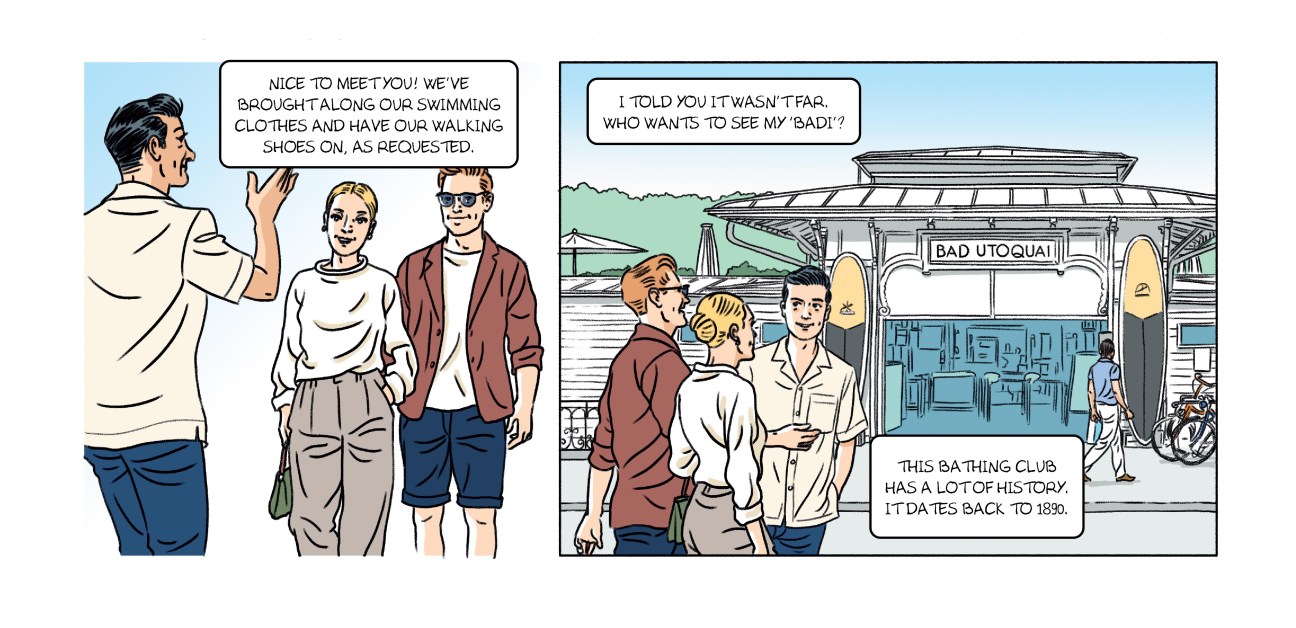

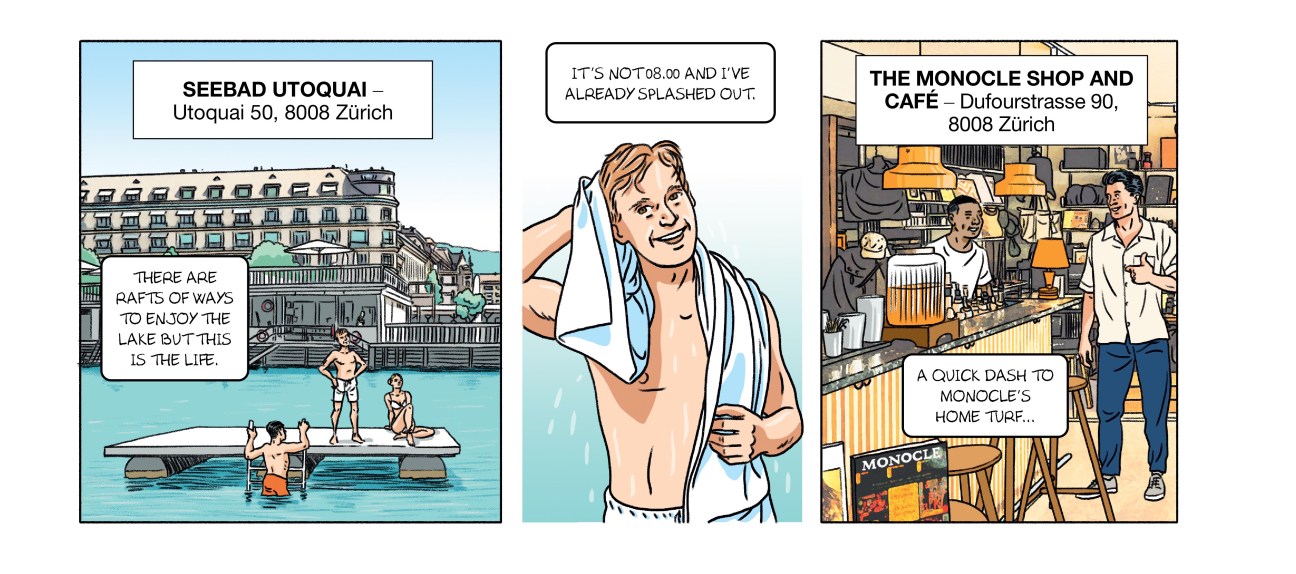

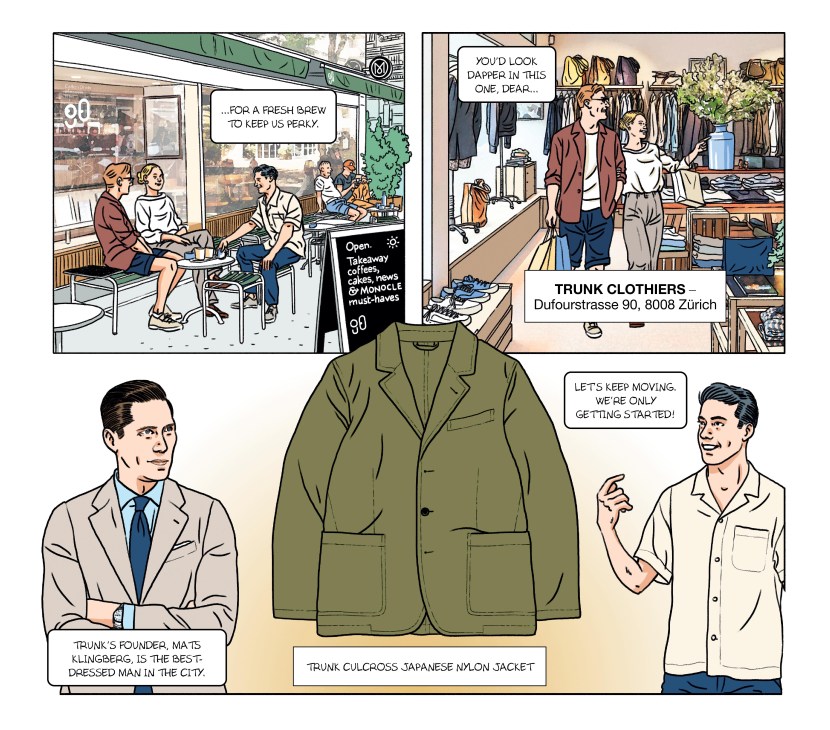

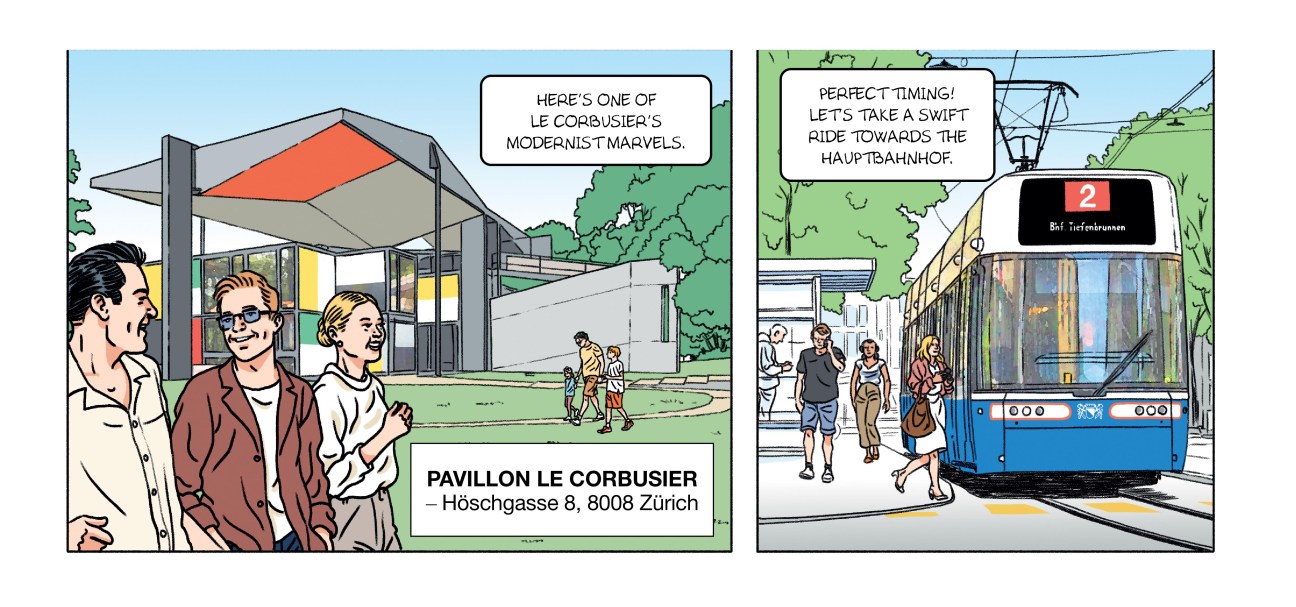

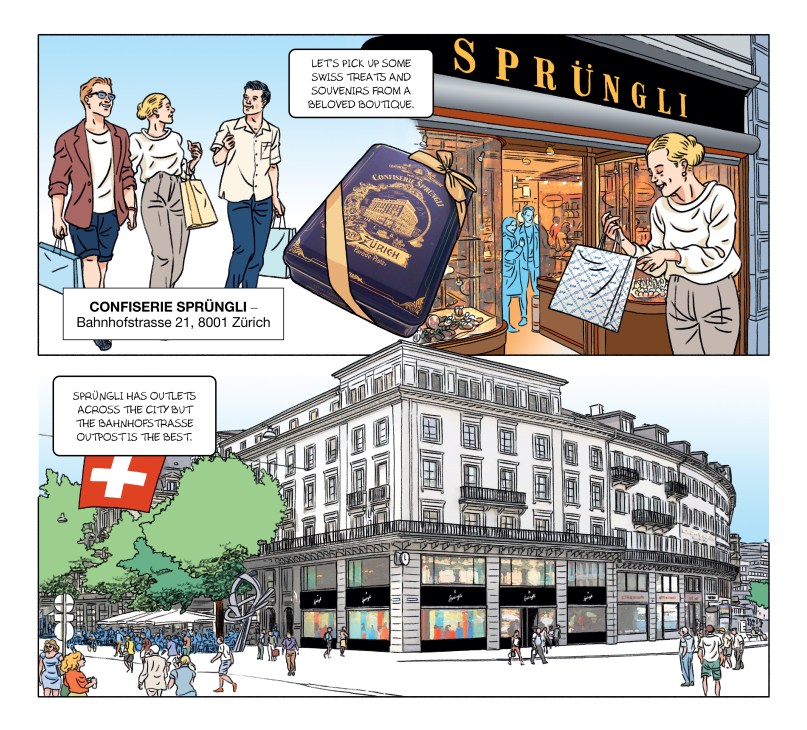

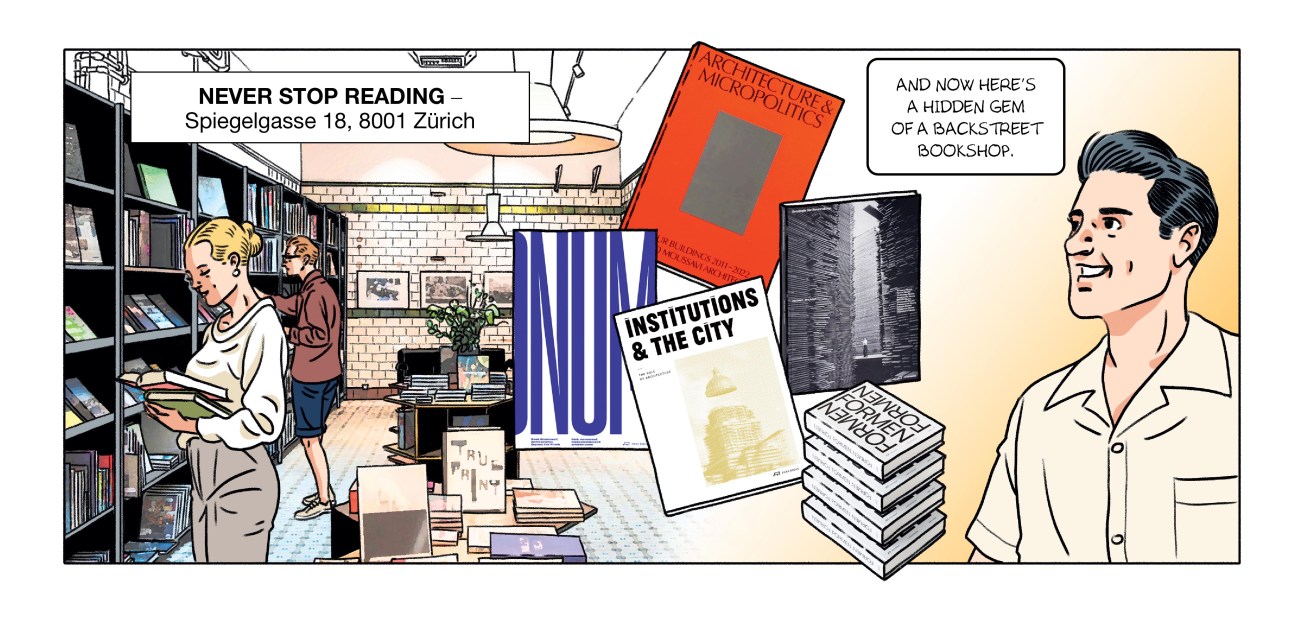

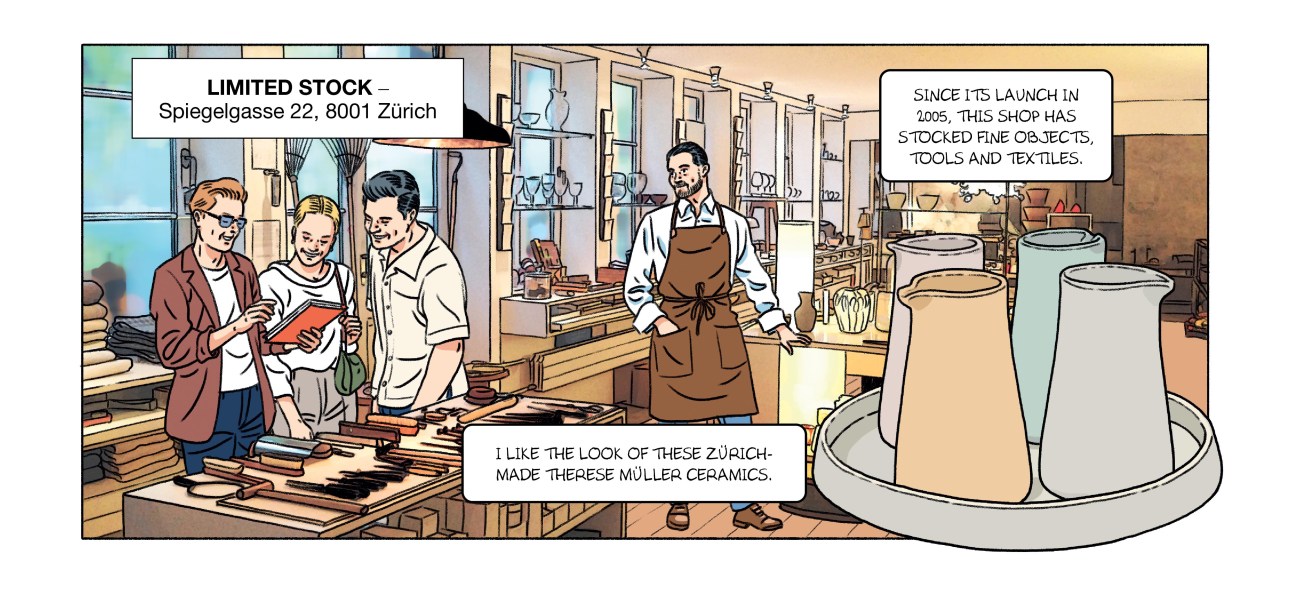

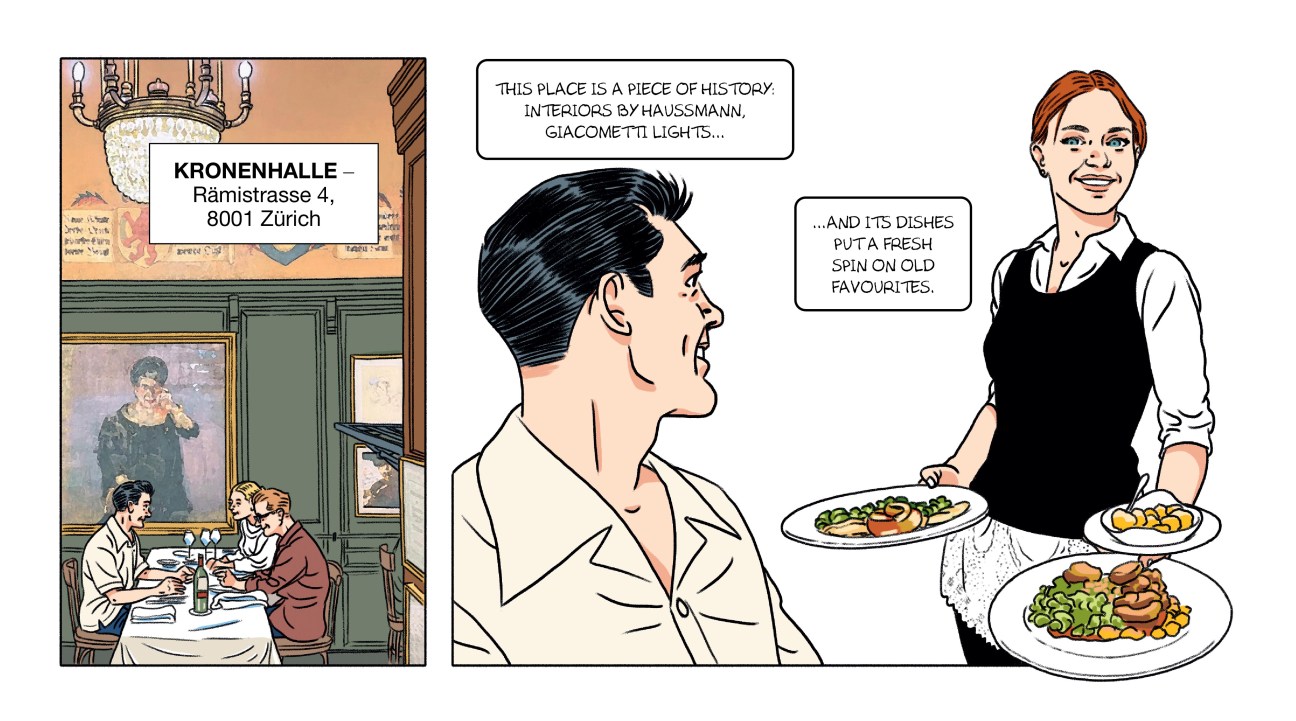

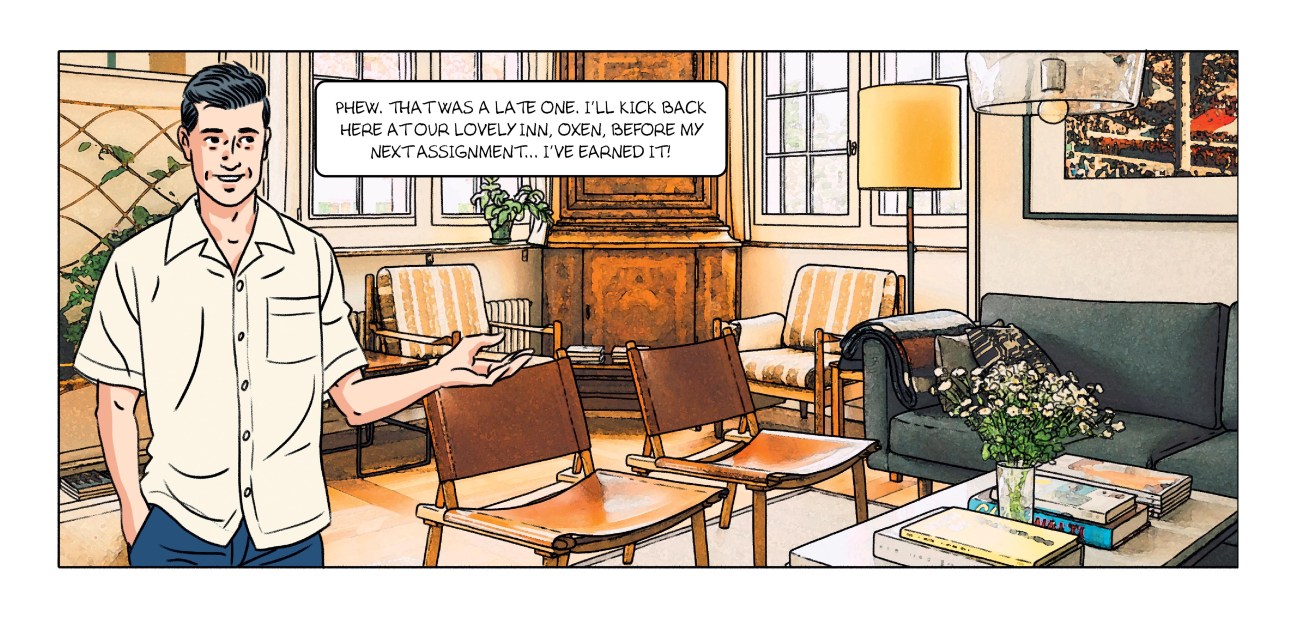

The Monocle Concierge’s guide to Zürich’s best offers

Click here to enjoy Monocle’s complete city guide to Zürich

Bjarke Ingels and ARM Holding are redrawing Dubai’s map – making it greener than ever

You can tell a lot about where a city is headed by the changes being wrought on its skyline. Dubai’s rapid rise and increased affluence is reflected in its built environment, composed of glass-clad towers and grand, palatial villas. Yet as more people put down roots in the Gulf city there is a growing market for a different style of development, which is human-scale and decidedly more grounded.

ARM Holding is one developer betting on such blueprints. The firm is redefining the housing stock of a city that has pitched itself to the world as offering luxury residences. When Monocle meets ARM’s CEO, Mohammad Saeed Al Shehhi, at the firm’s H Residence project in the Al Safa neighbourhood, the Emirati entrepreneur tells us how the city’s architectural and lifestyle habits are changing.

“Dubai is maturing,” says Al Shehhi, adjusting his ghutra headdress, as we look out over verdant lawns from a panoramic window at H Residence. “People want more intimate day-to-day experiences and a greater sense of community.” These are the pillars that have made H Residence and its sister development, The Fold in Jumeirah, sought-after addresses in the city. In May, Al Shehhi upped his game: ARM signed an agreement with renowned Danish architect Bjarke Ingels to create a vast megaproject in Dubai that could rewrite the rules of property development in the desert. “Together we want to build environments, not buildings,” says Al Shehhi.

The formula for ARM’s properties is simple: low-rise developments with crisp lines and natural materials, typically mixed-use with retail and dining positioned around pleasantly landscaped public spaces. In Dubai, this feels novel. When Monocle visits H Residence, the development’s Cipriani Dolci restaurant has a healthy crowd on the terrace, and there’s a mid-morning bustle at nearby Café Kitsuné. An enviable collection of art is scattered around the properties. All this creates a lived-in atmosphere – “village-like” is how Al Shehhi describes it.

“When a developer comes to you willingly sacrificing valuable floorspace for landscaping and public areas, it really means something,” says architect Tariq Khayyat, whose eponymous firm was commissioned to create ARM’s first two residential projects.

Al Shehhi admits that his vision was partly inspired by the clutch of pre-2000 bungalows dotted around the older parts of Dubai. Some of these houses are showing their age (many were built for oil workers) but they remain highly sought-after by UAE residents, yet are in dwindling supply.

The CEO has seen first-hand how the sands have shifted in the UAE’s market. After a stint at the helm of the Dubai Design District, he is currently secretary-general of UAE Media Council and runs the Emirates Racing Authority, which oversees the horse races that are deeply entwined with Emirati culture. This has put him in the room with both the city’s leadership and its creatives.

“When I started Huna, one of ARM’s premium property brands, in 2020, I looked at what real estate lacked in this city: greenery and community stood out,” says Al Shehhi. The UAE is no stranger to big name architects – both Norman Foster and Zaha Hadid’s glassy works dot the skyline – but Ingels was yet to make his mark. ARM Holding’s eagerness for green, public spaces caught the attention of the architect and his Copenhagen-based firm.

We’re told that the new, as yet unnamed megaproject will be on Hessa Street and feature residential units as well as retail, cafés, restaurants, art installations and more. The overall scale of the project is yet to be revealed but Al Shehhi’s team hint at multiple neighbourhoods that will occupy a sizeable footprint beside the Jebel Ali Racecourse. ARM has proven that it can build greener spaces with a sense of community, “but for our megaproject we want to be even more generous,” says Al Shehhi. The renders of the project reveal a terraformed plot, where rooftops are blanketed in greenery and apartments peek out from the treeline. All this is set inside a 5 sq km parkland that, according to the CEO, will be larger than London’s Hyde Park.

“I believe that for Emiratis and those who call the UAE home, living in a park is true luxury,” says Al Shehhi. “While pockets of this park remain private for residents, this is a gift for the wider community.” In a desert, this is a bold piece of urban planning. One may wonder at the environmental cost of keeping all those lawns looking sprightly. But the CEO is reassured by the principles of sustainability that have defined Ingels’ work to date, citing the carbon-zero credentials of Google’s new HQ in California.

There’s no doubt that it is a monumental urban intervention. “Bjarke’s designs so often feel utopian but, once delivered, they’re pragmatic and practical,” says Al Shehhi. “We’re both future-focused and we’ll judge its success 30 to 40 years down the line.” He adds that improving the health of residents and getting people moving in this car-centric city is a key part of the mission. “Any essential services will be within a 10-minute walk and cycle lanes will connect its neighbourhoods.”

ARM’s first developments were much smaller but this megaproject has the potential to redraw the city’s map. Many starry-eyed architects have worked in the Gulf’s fast-growing cities over the past few decades, often gazing upwards. Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, looms over the metropolis but even its shadow fails to shelter Dubaians from the sun’s rays. This vast residential development will change that – inviting all to bask in its natural shade, enjoy a cooling lake and native flora. As the city continues to attract and keep residents for the long-term, blue-sky thinking doesn’t look so fresh any more.

The CV

2008: Appointed deputy CEO of Dubai Media Incorporated (DMI)

2012: Made CEO, ARM Holding

2019-2020: CEO of Dubai Design District (D3)

2021: Appointed director-general of Emirates Racing Authority

2023: Launches Huna, ARM’s premium property brand

2023: Appointed secretary general of Dubai Media Council

2025: In May, ARM Holding and Bjarke Ingels Group sign agreement to work together

Worth the wait: Six new global restaurant openings to save on your map

1.

Oobatz

Paris

Dan Pearson moved to Paris to study international relations but found that there were other ways to win hearts and minds. The chef first made mouths water with a pizza pop-up at the Michelin-starred La Rigmarole. Now he’s back with Oobatz in the 11th arrondissement. The line-up features six pizzas, each made with market-fresh ingredients before its 90 seconds in the Swedish pizza oven at 480C. Monocle’s favourite has a marinara base, with pork and veal polpette and creamy caciocavallo. Call ahead as tables are tough to snag.

2.

Dodeka Piata

Athens

True to its name, Dodeka Piata (“12 plates”) offers a dozen dishes in celebration of the Greek concept of mezedes (sharing plates). The new restaurant in Koukaki is overseen by chef Pavlos Kyriakis and features mosaic-tiled floors and white linen tablecloths, with wooden chairs replacing the straw seats of a taverna. The menu is modest in volume but the smoked tzatziki and tyrokafteri, a spicy whipped cheese dip, will leave you satisfied. The pork gyros with paprika and onion are exceptional.

36 Odissea Androutsou, Athens 117 41

3.

Uno di Questi Giorni

Bologna

This restaurant from the duo behind Bologna’s much-loved Ahimè has been four years in the making. Whenever co-founders Lorenzo Vecchia and Gian Bucci were asked about the opening date, they’d reply “Uno di questi giorni” (“One of these days”); the name stuck. Designed by Trieste-based studio Metroarea, the interiors feature exposed wooden beams, contemporary lighting and cream-coloured sofas. But the real showpiece is the large open grill, where everything from Jerusalem artichokes to Po Delta oysters are cooked as part of the grill-only menu.

unodiquestigiorni.it

4.

Esra

Amsterdam

You’ll find this 26-cover Turkish offering in Amsterdam’s formerly industrial eastern docklands. Its appeal lies in the ever-changing menu of its London-born Turkish Cypriot owner, Selin Kiazim (pictured, on right, with co-owner Steph De Goeijen). “The food scene in Amsterdam is always evolving,” she says. “Esra’s menu switches with the seasons, sometimes even after a day.” Past menus have featured pollock with pistachio cream, and herring roe and Turkish eriste egg noodles with pickled maitake mushrooms and sheep’s cheese sauce. The wine list features appellations from Georgia, Croatia and Greece.

esra.amsterdam

5.

Bar Super

Barcelona

Bar Brutal and its bottle shop Can Cisa brought Barcelona’s most enterprising drinkers round to biodynamic wine when it opened in 2013. Its new sibling, Bar Super, is located next to the Mercat de Santa Caterina in El Born. Given its prime location, twin restaurateurs Max and Stefano Colombo, as well as winemaker Joan Ramon Escoda rely on cuina de mercat (market produce), to which they add the Venetian sensibilities that they channelled into their debut opening, Xemei, an Italian osteria in Poble Sec. At Bar Super, expect fresh prawns, succulent tuna carpaccio and colourful varieties of beetroot. The wine list features Catalan appellations from winemaker friends, as well as an in-house bitter made in collaboration with Genoese bodega La Ricolla.

barsuper.com

6.

Ghost

Bali

Ghost Kitchen and Record Bar mixes wood-fired cooking with a warm vinyl soundtrack. Executive chef Tim Stapleforth blends Balinese flavours and fresh produce with what he grew up eating in Queensland. Standouts include the babi guling crumpet, a play on the Balinese hog roast.

No 99 Jalan Pantai Berawa

Suite life: Four hotels that will leave you wanting for nothing

Quinta do Pinheiro

Algarve

It’s increasingly hard to find somewhere off the beaten track in the Algarve but Quinta do Pinheiro, a converted 19th-century farmstead, is one of them. Bordering the sandy dunes of Ria Formosa Park, this property is made up of five terracota-tiled cottages.

Lisbon-based architect Frederico Valsassina preserved key features of the buildings, such as their prominent chimneys, and used traditional materials including cane strips to create rustic living quarters.

A large water-storage tank once used by farmhands is now a pool. Each cottage comes equipped with a kitchen but Monocle restaurant favourite Noélia is a short drive east of the estate should you have a hankering for superb seafood.

quintapinheiro.com

Stockholm Stadshotell

Stockholm

Built in the 1870s, this historic building at Björngårdsgatan 23 has been restored as a 32-key hotel with a lounge, a sauna and a cold plunge. “Many of the original details have been preserved,” says founding partner Johan Agrell. Stockholm Stadshotell also offers two restaurants, one of which, Matsalen, is in the former chapel. Chef Olle T Cellton dishes up contemporary Nordic fare, such as wood-grilled fish. “Matsalen is about cooking without ego,” says Agrell.

The rooms and suites are rendered in muted tones, with furniture by Swedish company Tre Sekel, Italian linens from Liv Casas and bathroom fixtures by Lefroy Brooks. “The property’s architectural significance made it a compelling choice for a hotel because it has a soul,” says Agrell.

stockholmstadshotell.com

Chiemgauhof Lakeside Retreat

Bavaria

The Chiemgauhof Lakeside Retreat overlooks Lake Chiemsee, an untamed expanse of water nicknamed the Bavarian Sea. Halfway between Munich and Salzburg in Übersee, the property was acquired by hoteliers Dieter Müller and his wife, Ursula Schelle-Müller, in 2021.

Working with Milan-based designer Matteo Thun, they embarked on a major reconstruction. Thun conceived a contemporary barn built from larch, with oak-floored interiors and floor-to-ceiling windows that open up to the surrounding waters. In the restaurant, Maximilian Müller serves hearty Bavarian classics, while at the bar, Japanese chef Naoki Terai crafts sushi using fish caught from the lake.

chiemgauhof.com

Hotel Humano

Oaxaca

The so-called Mexican Pipeline on the country’s southern Pacific coast attracts an international surfing community to the town of Zicatela. Steps from the break at Playa Zicatela, Hotel Humano has become a popular stop-off. Architect Jorge Hernández de la Garza developed his idea with design firm Plantea Estudio for Mexico’s Grupo Habita. The result is a striking building defined by brutalist concrete and terracotta-coloured tiles offset by native tropical wood. The lobby, which opens onto the street, allows the interior and exterior to merge seamlessly.

In Humano’s 39 guestrooms, handmade hazel-coloured tiles by San Pedro Ceramics nod to the 1970s, while ecru twill curtains divide the ocean-view suites. In the evenings, chef Marion Chateau of Marseille’s La Relève brings a refreshing fusion of French and Mexican flavours to the dinner table.

hotel-humano.com

Change of art: The National Gallery Singapore aims the spotlight at Southeast Asia

Eugene Tan, the National Gallery Singapore’s CEO and director, might seem like a quiet academic but he’s unequivocal about the place of Southeast Asian modern art in the global ecosystem. “Our understanding of art is largely derived from Western art history, which has led many to think of Southeast Asia as one territory defined by colonial borders,” he says. “But it’s actually a multi-faceted network of art worlds.”

This summarises what the National Gallery Singapore, home to the world’s largest public collection of modern Southeast Asian art, set out to do when it opened in 2015. No other institution had tackled Southeast Asian art from a regional perspective. Accompanying this fresh approach was a mission to challenge Eurocentric narratives, prompting visitors to consider how Southeast Asian artists and movements intersect with dominant stories of art history. Reframing Modernism, jointly curated and developed with Paris’s Centre Pompidou in 2016, is one such seminal show, where works by significant regional artists, including Latiff Mohidin from Malaysia, were hung alongside iconic European names such as Henri Matisse for the first time.

Marking its 10th anniversary this year, the gallery has only grown in confidence. “As we’ve deepened our understanding and research of Southeast Asian art, we’re bolder at expanding Western definitions of art and spotlighting artists who have previously been overlooked,” says Tan. He cites the gallery’s recent retrospective on Singapore-born British postwar artist Kim Lim: sidelined in a male-dominated domain, she has since been recast in a new light.

The scale of their latest show, City of Others: Asian Artists in Paris, 1920s-1940s, illustrates Tan’s ambitions. It’s the first major comparative exhibition on Asian artists living in Paris during the vibrant yet challenging interwar period. With Southeast Asian art still heavily underrepresented on the global stage, the work of the National Gallery Singapore team is a major draw.

Eugene Tan, CEO & Director

After earning his phd from the University of Manchester, Tan held various roles in Singapore, from heading Sotheby’s Institute of Art to overseeing the development of the Gillman Barracks art district. He also curated the Singapore Pavilion at the 2005 Venice Biennale and the inaugural Singapore Biennale. In 2013 he was appointed as the National Gallery Singapore’s director and became Singapore Art Museum’s director six years later. Tan became CEO of both institutions in 2024.

1.

Chin Nian Choo, Creative head

Designs striking visual identities that bring exhibitions to life.

2.

Hisyam Nasser, Manager, learning & outreach

Champions artistic appreciation in younger audiences.

3.

Bruce Quek, Assistant manager, library & archives

Helps visitors find what they’re after.

4.

Vygesh Mohan, Programme lead, Light to Night Singapore

Curates art for the gallery’s flagship festival.

5.

Aun Koh, Assistant chief executive, marketing & development

Boosts the gallery’s presence around the world.

6.

Gracia Fei, Assistant manager, innovation & experience design

Reimagines the museum experience.

7.

Djasliana Binte Hussain, Assistant manager, digital infrastructure

Keeps tech troubles at bay.

8.

Anasthasia Andika, Assistant director, registration

Moves priceless artworks safely across the world.

9.

Lucas Huang, Senior manager, international partnerships

Works with international partner museums.

10.

Hafiz Bin Osman, Manager, collections management

Wows visitors with impactful displays of artworks.

11.

Muhamad Wafa, Assistant manager, mount making

Creates mounts to display artworks swiftly and safely.

12.

Chloe Ang, Assistant manager, content publishing

Develops catalogues and audio tours for visitors.

13.

Mark Chee, Deputy director, facilities management & operations

Works behind the scenes to keep visitors safe.

14.

Horikawa Lisa, Director, curatorial & collections

Shapes the gallery’s growing collection with collaborators across Southeast Asia.

15.

Aisyah Binte Johan Iskandar, Assistant conservator

Restores organic objects in artworks and artefacts.

16.

Koh Yishi, Manager, community & access

Shapes inclusive programmes and manages volunteers.

17.

Patrick Flores, Chief curator

Shapes the gallery’s artistic direction.

18.

Joleen Loh, Curator

Dives into the artworks and archives to find and tell stories that will resonate with audiences.

19.

Chris Lee, Assistant chief executive, museum experience & operations

Keeps the gallery running without a hitch.

Business agenda: Sustainable air travel with Helsinki Citycopter and Canadian companies making the most of Trump’s tariffs

Technology: USA

Good vibrations

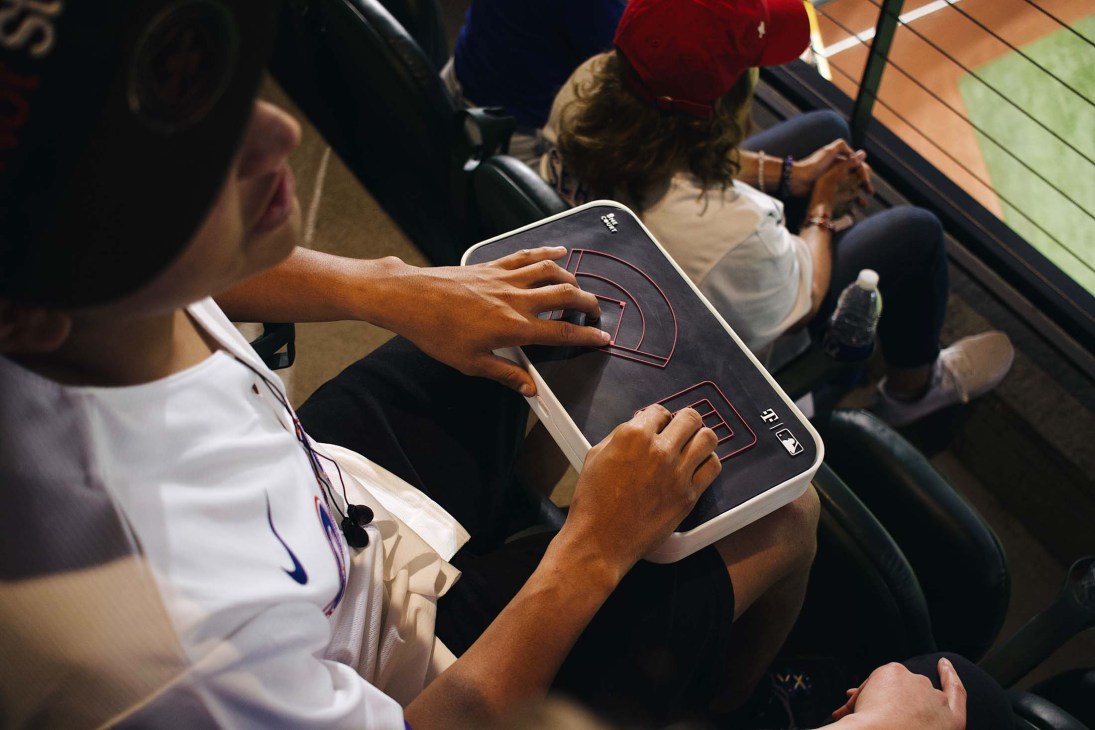

This NBA season, blind and low-vision basketball fans have been able to follow the action from their arena seats using a handheld device that describes the game through vibrations. Seattle-based start-up OneCourt was founded in 2021 and its haptic device debuted with the Portland Trail Blazers in January. The technology uses wi-fi and 5G to transmit data from arena sensors and cameras; coupled with a live broadcast, fans who can’t see the game can follow the action as the device signals, for example, where a three-point shot was taken.

The early-stage start-up has raised $475,000 (€420,000) from angel investors, including Microsoft’s ceo, Satya Nadella, and five NBA teams have signed up for the service. OneCourt has also engineered versions for baseball and football, which could be used during the Fifa Club World Cup that kicks off on 14 June. Co-founder Jerred Mace and his team currently make the OneCourt device in-house but he hopes to produce it at scale for an underserved market of sports fans who will be able to use it at home too. “We want to have a product that doesn’t just live in the stadium,” he says.

Transport: Finland

Out for a spin

Private helicopter transfers tend to be functional affairs, with cramped cabins and the lingering scent of jet fuel. Helsinki Citycopter, a Finnish firm founded in 2020, does things differently: the five helicopters in its fleet, which includes two Airbus ACH130s and an H125, have spacious interiors with leather seats, noise-cancelling headsets and efficient climate control. Powered by sustainable aviation fuel and modern low-emission engines, the aircraft also leave a smaller environmental footprint than many of their competitors. “There’s a unique advantage to helicopter travel,” says co-founder Joonas Nurmi, who spent 15 years with Finnair. “You get perspectives that you don’t see from a plane or car and you can land almost anywhere.”

Now the market leader in northern Europe, the company has steadily expanded, adding a Cessna Citation CJ4 private jet to its portfolio and launching a flight academy for helicopter and fixed-wing pilots. In addition to transfers, the firm enables travel to remote destinations, including Lapland, the Finnish archipelago and the Lofoten Islands. “Our product is nature,” says Nurmi. “And we fly where no one else does.”

helsinkicitycopter.com

Agriculture: Canada

Growth opportunity

When Donald Trump launched his first tariff broadsides at Canada’s economy in February, Canadian shopping habits shifted abruptly – away from American-made goods and towards more homegrown brands. That presents an opportunity for independent Canadian food companies. Among them is Lufa Farms, the innovative urban agriculture firm and marketplace for Québec-grown produce, which was co-founded in Montréal in 2009 by Lebanese engineer and entrepreneur Mohamed Hage and is currently expanding its reach across the country.

Inspired by the rooftop fruit-and-vegetable gardens that are a fixture of urban life in Hage’s home country, Lufa Farms operates as a network of rooftop hydroponic greenhouses on the flat roofs of industrial buildings, warehouses and big-box retail complexes in Montréal and across the broader region. The vegetables cultivated inside, which are watered by a system of rainwater- and ice-melt collection from the greenhouse roofs, are then picked and assorted into weekly grocery baskets.

Lufa Farms’ urban greenhouses not only reduce the distance between farm and table but have also activated parts of the existing urban fabric that have too long been dormant. Hage now operates an indoor farm and five greenhouses across the region, which serve about 35,000 customers every week, and has expanded deliveries to Ottawa. Lufa Farms’ success sends a strong signal that customers have a healthy appetite for this kind of urban agriculture – and that there’s ample room to grow.

lufa.com