The Entrepreneurs

Editor’s letter: Where to look for inspiration and how to act on it

People used to say that everyone had a book in them. Today there’s a creeping sense that every Jeff, Arianna and Elon is sitting on a business idea that can change the world – and not always for the better. But what makes a worthwhile business and what does it take to nudge people into starting one? Where and how does inspiration strike? And what do they learn along the way?

Metaphors only stretch so far but the publishing parallels run throughout this issue of The Entrepreneurs, Monocle’s handbook for budding business owners and anyone looking to pen the next section of their own story. So where to begin? Well, Jaime Daez of Fully Booked had little to no experience in retail when he began selling the architecture magazines that became the basis of his now thriving business, one of the Philippines’ leading bookshop chains. Good ideas can start small before growing in volume. Just look at Deezer, the Paris-based music-streaming service that pays artists fairly.

We also speak to career-switchers – one of whom traded his dreams of being a rock star to reinvent the toaster (he knows which side his bread’s buttered). We also solicit some advice from fashion firms on when to start, pivot and say a fond farewell. The business life cycle is celebrated too, from the ups and downs to the unexpected twists and turns.

Running your own concern takes graft but humbler company heads admit that there’s an element of being in the right place at the right time too. No, not in California: that moment has passed. Instead, we shine a light on Mexico, where entrepreneurs are rethinking everything from aviation to the art scene. We also visit Côte D’Ivoire to capture a moment of extraordinary optimism and opportunity in Francophone West Africa.

Elsewhere, we meet the CEO penning fresh lines at family-run firm Bic, which makes products that many people have but few feel they own, and the developers creating desirable new workspaces on Wall Street, where a fightback against remote working is in full swing.

We also profile three artisans crafting wares in the hearts of Florence, Tokyo and Stockholm in our visually appealing Expo – it’s about the businesses, of course, but also a meditation on what we all lose when cities become the exclusive remit of those with fat wallets, service jobs or white collars.

The idea of “making it”, of what success actually looks like, remains subjective. Most of the businesses featured across our pages, however, aim to give a little back. Perhaps they endeavour to include their neighbourhoods in their activities, improve the lives of their staff or solve problems without costing us the earth (figuratively or literally). So, whether you’re looking to start writing a fresh chapter or toss away the old manuscript and begin again with a blank sheet, we’ve got ideas aplenty and stories to share. Isn’t it time to turn the page?

Monocle’s Mexico Survey: the most exciting businesses and outposts of opportunity

Welcome to our sunny survey of smart thinking and innovative enterprise in Mexico. With a population of 130 million and a GDP of almost €1.53trn, the North American nation is a business powerhouse, with strong links to its US neighbour to the north – its largest trade partner – and the rest of Latin America to the south. A colourful country stretching from the windswept coastline of Baja California to the jungles of Chiapas, there are opportunities aplenty in diverse sectors for the savvy entrepreneur here.

While Mexico might have a solid backbone in heavy industry, agriculture and natural resources, in recent years it has made a name for itself for excellence in the worlds of gastronomy, hospitality and design. Indeed, there’s a lot more than meets the eye, from a booming film-production industry to architectural prowess. If you’re looking to make it here, you’ll quickly discover that lots of deals are made over a meal – meaning that, yes, in-person meetings trump virtual ones – and that knowing some Mexican Spanish slang can go a long way (it helps to know your chela from your chingón).

For our Mexico Survey, we dispatched our team of writers, editors and photographers to meet founders and learn about their projects all across the country, from San Miguel de Allende to Oaxaca City. Along the way, we found intrepid companies and individuals who aren’t afraid to go out on a limb to bring their passion projects to fruition, whether it’s a mission to make Mexico a regional e-mobility leader or producing a competitive jet plane to sell across the globe.

Taking flight

Oaxaca Aerospace is developing a “Made in Mexico” aeroplane in a land not known for making planes. Run by the Fernández family, the firm has built various prototypes for its Pegasus jet. The hope? To one day become a full-fledged international plane developer. To read more, click here.

High life

Amid Mexico City’s property boom, architect and developer Meir Lobatón Corona is rethinking the capital’s skyline. His Torre Gutenberg project isn’t about creating a temperature-controlled grey box. Instead, every floor has a large balcony with doors and windows that allow air and light to flood in. Click here to read more.

Star quality

Mexico is going from strength to strength in film. “There has been more growth in four years than in the past 15 or 20,” says Austrian Alexandra Ruths Braas, the enterprising co-founder of Romero & Braas, which makes original content and provides production services to international film crews. Read more about it here.

Happening hospitality

Oaxaca City is attracting an international audience. How are its businesses adapting to satisfy the needs of its modish visitors? Find out here.

Guadalajara’s art renaissance

Mexican creativity doesn’t stop in the country’s capital, as the artists leading this revival will attest. Discover your new favourites here.

Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

1.

Film production

“We came to Mexico and never left,” says Austrian Alexandra Ruths Braas, explaining how she ended up in the country alongside her business partner, Paul Krauskopf Romero, a German of Mexican heritage. The pair arrived in 2014 with a grant to make documentaries. More than 10 years later, Ruths Braas is still here, while Krauskopf Romero helms the Munich outpost of their company, Romero & Braas, which facilitates international film productions in Mexico, as well as making original content. “We help productions feel at home away from home,” says Ruths Braas. That means everything from location scouting to dealing with permits and sourcing technical providers. “There are people in Mexico who are used to an American way of working,” says Ruths Braas. “There’s amazing talent here.”

Netflix recently announced an investment of more than $1bn (€850m) in Mexican films and TV series over the next four years. The deal cements the country’s status as a rising filmmaking nation, which can only bode well for the likes of Romero & Braas. “There has been more growth in the past four years than in the past 15 or 20,” says Ruths Braas.

romeroandbraas.com

2.

Graphic design

Mexico City-based studio owner Adolfo López-Serrano didn’t set out to build his own studio. What began as a solo consultancy evolved into Base Agency in 2018, which today works with brands such as Revolve and Wix. Base is one of many Mexican firms helping to redefine where the world turns to for design. “We have a dynamic creative ecosystem here and great talent,” says López-Serrano. As a bonus, operating costs are relatively low.

By the end of 2024, Mexico was home to more than 60,000 graphic designers. UK-born Andy Butler is the founder of Deduce Design, a Mexico City-based practice that has worked with everyone from Nike to Grupo Habita, the country’s leading hotelier. International perceptions, he says, are rapidly shifting. “Mexican designers are being sought out not just for value but for their creative vision.”

While Mexico City leads when it comes to the concentration of designers, some of the strongest work is coming from unexpected places, such as Cocay Branding in Quintana Roo and Prizma Studio in Sinaloa. Walk through any Mexican city and you’ll see the fruits of the nation’s design scene all around you – in street signs, protest posters and hand-drawn menus. This colourful visual culture is making Mexico a magnet for creative talent.

3.

Hospitality

Mexico’s F&B sector is expected to grow by 6 per cent in 2025, buoyed by a rise in food tourism (which received a boost when Michelin launched its first guide to Mexico City in 2024). Opportunities abound for those trying something new. Take the capital’s Baldío, the nation’s first zero-waste restaurant and one of eight places in the city to have been awarded a green star by Michelin.

There are new openings across the country: in Mexico City, Masala y Maíz has a smart take on fusion, combining Mexican, African and Indian cuisines. In Guadalajara, Xokol has embraced the communal-table experience, while Mesa Temporal in Oaxaca offers a walking dinner in which patrons eat in different rooms, exploring specific ingredients in each. These risk takers are taking the country’s hospitality scene in fresh directions.

4.

Department stores

While US department stores such as Macy’s have been struggling, the picture couldn’t be rosier south of the border. Leading the pack is El Palacio de Hierro (The Iron Palace), a luxury player that has bet big on Latin American shoppers’ love of experiential shops, while also snapping up exclusive distribution deals with brands such as Loewe and Hermès. Last year its net profits were up by 23 per cent on 2023. How does it do it? First, it doesn’t skimp on costs. In 2015, for example, it spent almost $300m (€259m) on refurbishing its pyramid-like flagship in Mexico City. Second, it continues to branch out into new markets, with the most recent being in León in 2024.

El Palacio de Hierro isn’t the only department store that is demonstrating that multi-brand, in-person retail is a growth sector in Mexico. Take Liverpool, a group that dates back 175 years and operates 345 outposts across the country. Alongside a recently acquired 49.9 per cent stake in the US’s Nordstrom, it plans to open about 30 new shops in Mexico this year, many of which will be its smaller-format Liverpool Express stores. Meanwhile, another retailer, Coppel, has announced a $4.2bn (€ 3.6bn) investment in e-commerce and new shops. The skies are bright for Mexico’s department stores.

liverpool.com.mx; elpalaciodehierro.com

Images: Jeffrey Isaac Greenberg/Alamy Stock Photo, Anna Pla-Narbona, Alejandro Ramirez, Alejandra Velazquez

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

- Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

- Eight ideas for Mexican businesses that are ripe for the taking

- Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

- The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene

- Oaxaca Aerospace’s Mexican-built plane has beaten the odds and is ready for takeoff

Return-to-office mandates won’t keep workers in their cubicles – but a lavish workspace can

At first glance, 100 Pearl Street seems like a case study of the crisis facing downtown New York. Entire floors of this 1980s brick tower in Manhattan’s Financial District are empty – a problem that many of the building’s neighbours also face. A quarter of the office space around Wall Street is vacant after an industry-wide exodus to the home office.

Yet on 100 Pearl Street’s 28th floor, the lift doors slide open to reveal part of the pristine headquarters of asset management firm Alger, a hushed, double-height space with soaring windows and Jean Prouvé-designed lobby chairs. Inside, sharply dressed analysts dart between their desks and sparkly new boardrooms. “It’s a mark of success for any business to get to build your headquarters from scratch,” says Daniel C Chung, Alger’s CEO, sitting in a lounge chair in his corner office. “Our decision to invest was the result of a combination of terrific space, the views and a good deal.”

Amid a glut of unwanted commercial real estate in New York, some companies are taking advantage of reduced rents to secure bigger and better headquarters. Alger, which has a relatively modest $28bn (€23.7bn) in assets under management, signed up for its new office in 2020 and moved in two years ago. Its three floors – of which the upper two are newly built – feature felt-lined conference rooms and custom-made wooden workstations for a staff of 170 stock traders, wealth managers and analysts. The team was previously based in a cramped, open-plan office in Midtown.

There’s a heated competition emerging at the upper echelons of Manhattan’s commercial property market. To lure staff back to the office, canny firms are spending lavishly on amenities, furnishings and location, all in a bid to outdo each other in terms of digs. Alger’s trophy HQ is just one example of many.

Rising above skyscrapers built by Gilded Age industrial tycoons, the latest addition to New York’s silhouette is a 423-metre-tall bronze skyscraper that will house the new headquarters of multinational finance corporation JPMorgan Chase. Designed by UK-based practice Foster 1 Partners, it is expected to be completed later this year. Any old class-B office space simply won’t do and the battleground includes everything from in-house gyms and on-site doctors to plunge pools and the size of the fish tank on the executive floor.

But it’s not all about the frills. The property race among New York’s high-flying firms is about projecting an aspirational, even somewhat cinematic image after years of dour pronouncements about the death of the workplace. “The office has turned from a mere nine-to-five place into a cultural destination,” says Jonathan Olivares, the design director at Knoll, a firm that has furnished corporate America since the 1950s.

This new crop of trophy offices often evokes some of the glamour of Madison Avenue’s mid-century heyday (and there’s more than a nod to the sets of 1960s-set TV drama Mad Men in one or two corner suites that Monocle visits). For many workers, it’s no longer necessary to be physically present to complete their tasks, so bosses are realising the importance of creating spaces that both look the part and make staff feel part of something exciting.

“I couldn’t really justify [Alger’s investment in its HQ] beyond the fact that it’s inspirational to employees,” says Chung. “The dream of coming to New York is associated with the city’s glamour, its nightlife and the idea of successfully making a career in one of the world’s most competitive markets.” He gestures around the C-suite, with its views of Manhattan and Brooklyn. “I tried to make our office a place where a young person might come in and say, ‘I want to be here.’”

Before the lease was signed, Chung had already chosen the interior designers for Alger’s new base: Brittney Hart and Justin Capuco, the founders of New York-based studio Husband Wife, best known for elegant residences. The pair spent three years on the $15m (€13.2m) project, tailoring their work to the wishes of Alger employees. “We booked a conference room for a day and spoke to every senior member of staff and most junior ones,” says Capuco. “It was clear that nobody wanted their workplace to feel like an old-fashioned cubicle farm.”

For the layout, Hart and Capuco drew inspiration from the glass-pavilion homes of early Californian modernism, creating “floating” offices with metal blinds for privacy. The meeting rooms come in hues of blue – Alger’s company colour – with carpeting and felt walls, scalloped ceilings, curving eucalyptus-wood desks and presentation screens inspired by science-fiction films. In the open-plan workspaces, where some type of cubicle was unavoidable, they designed roomy nooks crafted from stained oak, with fabric panelling for optimal acoustics. Seating, all in black leather, comes courtesy of mid-century power-office designers Marcel Breuer, the Eameses and Mies van der Rohe.

“We are seeing a complete market split,” says Volker Zinkl, the head of real estate for the US subsidiary of German reinsurer Munich RE. “The top offices are all going, while downtown is 40 per cent empty.” Zinkl shows Monocle around one of the firm’s flagship assets: an Eli Kahn-designed office tower on Madison Avenue. Since buying the building in 2020, the new landlords have been busy upgrading its amenities and adding spaces for a café and a bar.

“We see ourselves almost as hotel directors,” says Zinkl. “Our tenants are fighting to attract top employees, retain talent and impress their clients.” He points to the bouquets of cherry blossoms on the receptionist’s desk. “Take these flowers. We spend $3,000 [€2,560] every month on them. When you have thousands of people passing by every day, you might as well make it count.”

The seating that Zinkl bought for the lobby – a pair of beige curving couches on aluminium legs – is something of a secret handshake in the world of top-flight office interiors. Last year, Italian furniture company Unifor began producing the Andromeda collection, which also includes a credenza and tables with a mirror-like polish; its designer, LSM, has become a go-to architect among the new crop of trophy offices in Manhattan.

“We always ask our clients, ‘What do you want and what are your business goals?’” says Debra Lehman Smith, LSM’s founding partner. In the case of a financial firm on Park Avenue – one of the firm’s recent projects – the answers to those questions were translated into pleated marble walls and a full suite of Andromeda furniture. LSM has also kitted out a double-height atrium inside Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram building for private equity firm Centerbridge Partners.

As Monocle meanders from office to office in neighbourhoods from Wall Street to Midtown Manhattan, the Dow Jones stock index is taking a similarly zigzagging route. Donald Trump’s various pronouncements are shaking up the economy; bankers and traders have found themselves at the centre of it all. We accompany Lehman Smith for a brisk stroll up Fifth Avenue towards the skyscraper at Rockefeller Center, an art deco marvel with a lobby covered in green Tinos marble. In 2018, when the Rockefeller family office launched an expansion to become a full-fledged financial firm, it turned to LSM to help define its physical footprint. The team toured the available spaces in the company’s namesake tower and settled for a high-ceilinged space with a terrace overlooking St Patrick’s Cathedral. “No matter how great you are, if you’re in a low, dark space, it’s never going to work,” says Lehman Smith. The result is an open-plan office with stripped-back columns revealing the tower’s original iron structure. It has served as inspiration for some younger firms seeking to evoke previous eras of corporate power with their HQs.

“We organise our client cocktails, art exhibitions and town halls here,” says Michael Gaab, Rockefeller Capital Management’s chief administrative officer. “This space represents our company’s heritage.”

Not every firm enjoys an address that’s as iconic as the Rockefellers’ but the centre of gravity in New York is shifting. Many companies have decamped to the lofty steel-and-glass heights of Hudson Yards, a development on Manhattan’s western waterfront that stood desolate for years after opening in 2019 but where rents now begin at $1,400 (€1,190) per square metre – for comparison, a grade-A office in the City of London will set you back less than $1,080 (€920) per square metre. In Midtown, those buildings that are fully leased out tend to be architecturally significant skyscrapers, such as the Seagram, even if tenants pay rents starting at $1,615 (€1,380) per square metre, compared to the area’s average of $900 (€770) per square metre.

In 2020, Alger’s decision to relocate downtown to the old heart of US finance seemed like an edgy decision, given that the area was emptying out. “We’re a little contrarian,” says Chung. Outside the office is Harry’s, a legendary Wall Street watering hole, which used to be packed by 16.30 in the old days with a hard-drinking crowd of investment bankers, stock brokers and portfolio managers. “Then they would all rush to their commuter trains and, by 18.30, this area would be a ghost town,” says Chung. After a long lull following the pandemic, however, the Financial District has become a place to linger after dark. Quite a few places to shop and dine have launched in the past year, including The Observatory, a private dining lounge on the top floor of an art deco apartment building, and department store Printemps, which opened in March on One Wall Street.

These green shoots suggest a surprising revival for New York’s traditional office heartland, even as so much floor space remains empty. It is attracting a new breed of workplace: at 161 Water Street, the vacant former HQ of insurer aig has been transformed into Water Street Associates, or WSA, a new hub courting creative businesses. The drab 1980s tower has been reimagined with travertine floors, cognac-coloured carpeting and faux cubicles assembled from usm shelving, as well as liberal pickings from the catalogue of vintage furniture reseller 1stDibs. WSA has a concierge and butler service; there’s a floor with a barber and an acupuncturist. The tenants include the old guard of law firms and financial start-ups, alongside a crop of designers, stylists and upstart media companies. WSA has expanded to nearby 180 Maiden Lane.

“There’s no reason to only offer young people Wework nightmares,” says WSA’s Sam Wessner. “If you actually make it nice, people will still want to work in offices.”

Reflect Orbital: The aerospace startup ‘turning on the sun’ at night

Ben Nowack is obsessed with energy. The 29-year-old Cape Cod-born has explored ideas such as damming the oceans to harness the tides, flattening mountains with gravity batteries and even latching onto the moon with a vast cable. In high school, he says, he built a kind of fusion reactor as a science project.

One of his ideas is now poised to take flight. The CEO of Los Angeles-based start-up Reflect Orbital plans to launch thousands of satellites into space, equipped with mirrors that can reflect sunlight to Earth. By 2030 the company expects to have enough satellites in orbit to provide solar farms with 200 watts of energy per square metre – equivalent to the sun at dawn and dusk – during the evening hours of peak consumer demand. It also hopes to sell illumination to anyone who fancies an extra hit of sunlight, from concert and festival promoters to remote construction sites. “The range of applications for our service encompasses almost anything that an individual can do during daylight hours,” says Nowack.

(almost) on his shoulders

The premise has its sceptics – Youtube astrophysicists relish taking pot shots at Reflect Orbital – but it has also attracted serious interest. The company recently landed $20m (€17.42m) in Series A funding, including investment from Silicon Valley heavy-hitters Sequoia Capital and Lux Capital, and had an audience with Hamdan bin Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the crown prince of Dubai, about the project.

There is an emerging global interest in what might become one of the US West Coast’s signature exports within this decade: bold, upstart energy businesses. Big Tech’s embrace of power-hungry artificial intelligence and cloud computing has generated voracious demand for electricity. Now there’s a gold-rush atmosphere among start-ups seeking to innovate clean energy sources, from mini-nuclear reactors to fusion power.

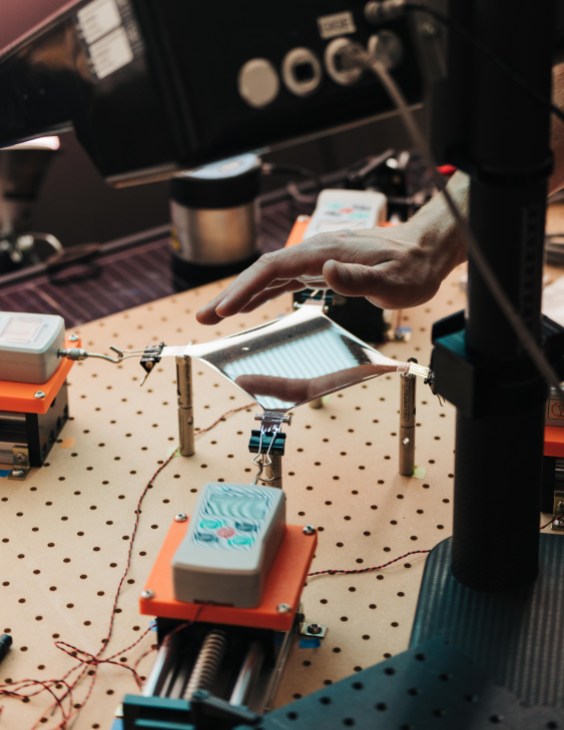

But Reflect Orbital is looking for ways to better harness humanity’s oldest source of energy. When Monocle visits the company’s lab in Hawthorne, a small city in Los Angeles County that’s home to a slew of aerospace start-ups, Nowack and his CTO, Tristan Semmelhack, are eager to show off their progress since founding the business in 2021. (First, however, your correspondent must show proof of US citizenship and agree not to photograph certain aspects of the satellite-making process in order to comply with laws around technology with national-security implications.)

As early as next spring, the company will launch a 100kg satellite packed into a box the size of a microwave. In space, the satellite will unfurl four triangular panels creating an 18-by-18-metre surface mounted to booms, attached like sails on a ship’s mast and position itself in orbit along the line separating daytime from night-time on Earth. Nowack and Semmelhack say that the system is reactive, allowing for precision angle changes within seconds as the Earth rotates. While this first satellite can only generate about four minutes of daylight over a 5km radius, the founders say that a ring of 18 satellites trained on the same location could illuminate one spot for an hour.

The technology sounds like sci-fi but it has precedents. In 1993, Russian satellite Znamya cast a 5km-wide beam the strength of a full moon onto a narrow stretch of Europe for a few hours. In April 2024, Nasa launched the ACS3, a spacecraft that successfully unfurled a solar sail, which reflected sunlight to generate propulsion.

The key difference between Reflect Orbital and its space-agency predecessors is that the team wants to turn a profit. The company’s 22-person crew, expected to grow fast this year ahead of the first launch, builds its own components and does much of the fabrication itself on a lean budget. The prototyping workshop is a tinkerer’s paradise of Milwaukee tools, Fiskars rotary blades and Scotch tape, and a sample reflecting sail is laid out in a brand-new “clean room”. Semmelhack, a laid-back New Yorker climber with shaggy blond hair and wearing a flannel shirt, brings out a palm-sized scrap of the ultra-thin sail material and lets it float in the air like a plastic bag.

Reflect Orbital’s do-it-yourself spirit is also evident in its car park, where the team shows off a homemade, 13-metre-long oven in which carbon fibres can be baked into booms. These coil like a tape measure, keep the reflective sail taut and weigh almost nothing.

Building the oven cost a mere $40,000 (€34,000) and took the team a month. “If we were Nasa, this would be a million-dollar device – and the project wouldn’t make any money,” says Semmelhack. “We don’t have a huge amount of capital or time, so we have to build stuff quickly and cheaply that works well enough for our purposes.”

One block away is SpaceX’s original headquarters and the tip of its first successfully recovered Falcon 9 booster can be seen peeking out from among the warehouses. Elon Musk moved SpaceX from California to Texas in 2024 but talent remains clustered in Hawthorne. “It’s very easy to get things built with machinists around every corner,” says Nowack. “If you need the perfect laser weld, the guy who did it for the SpaceX and Nasa missions is here.”

Nowack interned at the pioneering commercial space company and its monument, put on permanent display by Musk in 2016, is a visible reminder that proof of concept is vital in this industry if you want to be taken seriously. The clock is ticking on Reflect Orbital’s deadline to load up a rocket and deploy its first sail in the spring of 2026. Yet the commercial space industry has become astoundingly cheap by satellite-launching standards – just $6,500 (€5,500) per kilogramme, or eight times cheaper than it was on Nasa’s now-retired space shuttles – and this is presenting an opportunity for space start-ups such as Reflect Orbital that want to get their projects off the ground.

In order to deploy 100 satellites per rocket launch and reap what it believes could be billions of dollars in revenue, the company is banking on the cost of joining such launches continuing to decline. It is currently fine-tuning its design in a bid to get its satellite-production costs down from $2m (€1.7m) to less than $100,000 (€85,000) per unit.

Where that revenue will come from is still uncertain. But Reflect Orbital has its theories: municipalities seeking to save on street lighting, those engaged in search-and-rescue operations, construction firms operating in remote areas that want to extend the working day – and even Arctic villages hoping to make winters more bearable (bringing light to Russia’s Far North was one of Znamya’s goals).

Objections to the technology aren’t hard to imagine, not least the light pollution and its potential to disrupt the rhythms of flora and fauna. Never mind the complaints from neighbours who don’t want dawn and dusk extended. The company has had preliminary conversations with environmental groups concerned with the matter but the founders say that the light will be dispersed rather than a harsh spotlight and the technology will allow them to quickly point the satellites elsewhere. “Give us four minutes,” says Semmelhack. “If everyone hates it, we can turn it off.”

That might sound like a shaky business plan but there are more remote deployments of Reflect Orbital’s technology that make sense. Semmelhack imagines lighting up a pasture at the behest of a rancher or a ceremony for a sheikh. “We have the benefit of [working across] large areas of land that are controlled by very few people.”

Reflect Orbital started taking applications for its service last autumn and, according to the company, was flooded with 164,000 requests from 157 countries. The company is planning a 10-location “world tour” once the first satellites are aloft, imagining the kind of mass gatherings that a solar eclipse can attract. Sunlight on demand is a large-scale parlour trick that will generate hype. But what drives Reflect Orbital’s mission is the energy business and making the most out of solar panels, says its chief strategy officer, Ally Stone. “It’s a way to unlock value from an already financed, already operating solar asset.”

Reflect Orbital is one of many West Coast enterprises exploring new power-generation schemes as Big Tech pledges to stay true to its commitments to net-zero emissions. For years, data centres have been popping up along the hydropower-rich Columbia River Basin. But the current grid network is insufficient, says Julia DeWahl, a Los Angeles-based angel investor and co-founder of microreactor start-up Antares. “Forecasted energy demand is a step-function increase in growth largely driven by AI,” she says.

Every AI-powered Google search uses 10 times the energy of a traditional search. In response, its parent company Alphabet, alongside Amazon and Meta, have pledged to support efforts to triple nuclear-power production by 2050. Microsoft is resurrecting Three Mile Island, a Pennsylvania nuclear plant infamous for a 1979 meltdown. Meanwhile, there are entrepreneurs across North America working on small scalable nuclear reactors, such as the Bill Gates-backed Terrapower, which plans to be running in Wyoming by 2030. Elsewhere, in the Seattle area, start-up Helion is working on the world’s first fusion-power plant.

“After so many years of software start-ups, there’s a boom around building real things,” says DeWahl. The location of many of these companies is no accident. “There has always been so much innovation on the West Coast.”

Not every idea taken from a sci-fi novel will work but there’s smart money betting that Reflect Orbital can pull it off – with the potential for a considerable return on investment too. The founders expect public support for their solar spotlight, even if that might partly be tech-bro swagger. “If you zoom out and look at this with a bit of perspective,” says Semmelhack, “this is just so cool.”

20 hard-earned business lessons from entrepreneurs at the top of their game

Want to build a business that works? We have gathered 20 lessons from global entrepreneurs and industry leaders at various stages of their journeys. In candid conversations on Monocle Radio, they shared with us their thoughts on what it takes to succeed, from carving out a niche and building a purposeful brand to knowing when to trust your gut or pivot with grace. The ideas here span six continents, with sharp insights from founders and CEOs in fashion, media, manufacturing and robotics. Some spotted overlooked markets, while others turned to the past, stacking skills to create something new. What unites them is a willingness to rethink the obvious, be bold and keep building, whatever the size of the idea or the field they’re in.

For more smart thinking and fresh perspectives, tune in to Monocle Radio’s weekly shows The Entrepreneurs and Eureka, your blueprint for the best in business, retail and leadership.

1.

Pursue what challenges you

“I didn’t set out to start a beauty brand. Cutting through in such a saturated market is incredibly challenging – it’s a steep hill to climb. But I saw problems that were worth solving and it felt meaningful to me to try. I decided that I wanted to bring new thinking into the industry and make it more sustainable, introducing products that combine nature and efficacy.”

Emma Lewisham

Co-founder and CEO of Emma Lewisham skincare

2.

Value traditional techniques

“Greece has an incredible jewellery heritage that isn’t celebrated enough. I have always thought that ‘Made in Greece’ should mean something, just as ‘Made in Italy’ does. Seeing the artisans of the country at work their craftsmanship, the goldsmithing techniques – made me realise that we could create something beautiful that was rooted in culture and truly worth sharing.”

Alexia Karides

Co-founder and CEO of London-based jewellery brand Ysso, whose handcrafted pieces are made in Athenian workshops

3.

Digital doesn’t have to mean disposable

“Speed tends to be prioritised over quality in digital journalism. Newspapers often save their well-researched long-form content for print, while digital news outlets churn out quick, low-quality updates. We saw that there was demand for depth over volume amid the relentless breaking-news cycle. The more polarised society is, the greater the need for a product that takes its time.”

Tav Klitgaard

Co-founder and group CEO of Danish digital-only news outlet Zetland

4.

Turn a pain point into match point

“As a tennis player, I was always annoyed by how much time I would spend picking up balls instead of actually playing. So we built an autonomous robot that does it for you. Other players immediately supported us because it’s a common frustration in the sport. We knew that we had something that would do well, not just in the US but in all big tennis markets.”

Haitham Eletrabi

Co-founder and CEO of Alabama-based company Tennibot, which makes ball-collecting robots for racquet sports

5.

Take advantage of overlooked market opportunities

“Growing up in Oaxaca, I would find delicious mezcal everywhere. But many people in Mexico City dismissed it as a cheap peasant drink. I never imagined that it would become a global phenomenon but once the big chefs in the capital started talking about it, tourists came and everyone wanted a taste. At the start I just wanted to keep my grandfather’s recipe alive.”

Yola Jimenez

Founder of Yola Mezcal, an artisanal brand based in Oaxaca, Mexico

6.

Build in sustainability from the start

“The things that you need when you’re young and moving in with your partner for the first time aren’t what you want when you have two children and a bigger house. We wanted to design furniture capable of growing with our customers so that they don’t have to replace all their pieces – they can be adapted to evolving needs.”

Anders Thams

CEO and co-founder of Moebe, a Danish design brand making interior goods that are easy to ship and simple to repair

7.

Keep things simple

“Over the years, we have spent a lot of time thinking about the growth of the team and what happens when you bring 5,000 people together. Our biggest challenge is how to keep the culture vibrant, with everyone working together, while setting increasingly ambitious goals.

“At Canva, we have a two-step plan. The first is to become one of the most valuable companies in the world. The second is to do the most good that we possibly can. When we bring in an investor, we ensure that they are very clear about what their money is going to do, what our vision is, what our mission is and what we are trying to achieve.

“One of our core values is to make complex things simple. Thirteen years ago, when we set out to apply this to design, we wanted to make a product that wasn’t just serving the 1 per cent of the world that could think deeply about the subject for 10 hours per day. We wanted to produce something that would unlock the power of design for everyone – what we call ‘Empowering the world to design’. The first version of our graphic design platform did this and we spent the next 12 years making sure that the product stays simple but powerful.

“Creating a better organisation and being a responsible actor within society is a key part of Canva. We have given away more than $1.5bn (€1.3bn) worth of our product every year to teach students and benefit non-profits all around the world. That’s an amazing thing that’s extremely simple for us to do, because we just flick a switch in our database to give people the product for free. It helps to improve people’s lives and their organisations, and non-profits to drive their mission. Students are able to learn more effectively and teachers can engage their students in a better way. It’s a win-win.”

Cameron Adams

Co-founder and chief product officer of Australian software company Canva

8.

Embrace uncertainty

“We often strive to predetermine things. The temptation is to decide, ‘This is how my business should run.’ But the longer I do this, the more I realise how important it is to be adaptable. You never know how things will go on any given day, so you need to be able to pivot.”

Tom Àdam Vitolins

Founder of Berlin-based loungewear brand Tom Àdam, renowned for its pyjamas

9.

Stay in your own lane

“I launched my brand to create my own space, not to fill a gap. At the time, South Korea’s perfume market was almost nonexistent. It was a risky move but I believed in my vision. I’m not trying to please everyone. I would rather know that one person really loved a scent. My biggest fear is making a forgettable fragrance that no one has an opinion about.”

Jun Lim

Founder and creative director of Born to Stand Out, an artistic perfumery in Seoul

10.

Break the rules for long-term growth

“Businesses need to make money if they want to continue to exist and thrive. Expansion can present new challenges but the shackles have been kind of thrown away a little bit. We always try to remember that we don’t need to be constrained by a certain set of rules. This allows all of the things that we love and care about – from hospitality to music, art and design – to shape and influence what we do next.”

Johnny Smith and Daniel Willis

Co-founders of hospitality group Smith & Willis

11.

Start in a niche to gain momentum and credibility

“We began in the indoor-climbing industry because we knew that it was the fastest way for us to create an impact as we had access to the community. That gave us a way to test our material and connect with people who are eager for a solution to the problem of plastic use in climbing gear. Starting small helped us grow our vision in a way that felt organic.”

Marta Agueda Carlero

Co-founder and CEO of Material Alternative Design, a Berlin-based company making high-performance materials using mycelium, the root-like structure within mushrooms

12.

Unleash your inner nerd to find the recipe for success

Lena Patriksson Keller: “While I have the greatest respect for anyone who has a full lifestyle brand, Jonas and I agreed to do something very specialised. We said, ‘Let’s be nerdy, go deep and dive into something where we can excel on all levels.’ Jonas especially has a long history in denim. Does the world need another denim brand? Probably not – but we felt that there was space for one with European values that moved away a little from Americana.”

Jonas Clason:“We don’t use so many different elements but concentrate on the perfect fit, fabric and packaging, as well as on sustainability. We wanted to team up with industry leaders to create something new – owning the supply chain, threads and fabrics, and so on. We started with a laboratorio in Castelfranco outside Bassano del Grappa in Veneto. Instead of sending patents and finishes to a supplier,

we made the ‘recipe’ there.”

LPK:“There is a completely different level of knowledge today among customers and in the supply chain. At the beginning, we said that the industrial set-up was crucial for the whole business because a European brand is all about culture. As a new company, we were fortunate to have a close relationship with suppliers, developing all of these things for us. At an early stage, we said, ‘What Loro Piana is for cashmere, we want to be for denim.’”

Jonas Clason

Co-founder and creative director of Jeanerica

Lena Patriksson Keller

Co-founder and chief brand officer at Jeanerica and executive chair of the Patriksson Group

13.

Rebuild long before you’re forced to do it

“We took the whole company apart and rebuilt it to be more sustainable. Every business should do the same. Even without a crisis, act as though you have one. Re-evaluate your team, costs and core offering. Strip it all back, be clear on your purpose and build a strong, focused strategy.”

Johan Hellström

CEO and owner of Swedish haircare brand Björn Axén

14.

Seek out like-minded collaborators

“I wanted to create the first African-owned high jewellery brand that honours the communities where the gemstones that are used come from. The first PR firms that I approached told me to tone down the African influence as it would be a hard sell with editors – so I chose to work with someone else. The whole purpose of founding this business was to celebrate that African heritage.”

Vania Leles

Founder of African high-jewellery brand Vanleles

15.

Build before you’re ready

“We didn’t have engineering backgrounds but we kept experimenting. We tinkered with existing technology, tested countless prototypes and learned from every failure. Eventually, we realised that our makeshift headsets could become a business. The real breakthrough came when we saw the demand for personal use so we shifted focus to the hardware and it opened up a whole new world for us.”

Sheera Goren

Co-founder and CEO of Zygo, the world’s first underwater streaming headset

16.

Craft a compelling brand story

“We made a website before we even had the product. My background as a photojournalist came in handy because I knew that a purpose-driven story resonates with people. So I wanted to focus on longevity and build a narrative that reflects my connection to Argentina – my homesickness for the country, Buenos Aires and the artisan craftsmanship that you find in Latin America.”

Victoria Aguirre

Co-founder and creative director at Pampa, a rug and homewares brand in Australia with roots in Argentina

17.

Turn your skills into toys

“I have a background in advertising and graphic studios – I spent years on creative teams before starting my own project in my forties, inspired by my five-year-old. I wanted to express what I had learned about creativity so I started a toy brand with designs that encourage open-ended play. Children think that they’re playing with toys but they’re really tools for building critical skills.”

Nuria Torras

Founder of Lekkid, a Barcelona-based toy brand

18.

Future-proof your industry

“You can learn the basics of ceramics in a matter of months but it takes decades to master it – and our workforce is ageing fast. That’s why every craftsperson should be training someone who is 10 years younger to ensure continuity and knowledge transfer. Our most experienced decorator was taught by her mother. Now we’re teaching her daughter.”

Sarah Watson

Owner and creative director of Balineum in London and Phoenix Tile Studio in Stoke-on-Trent

19.

Success isn’t in still waters – so learn to ride the waves

“Most great entrepreneurs feel like outsiders. They’re flawed, restless and often misunderstood. But strength lies in seeing beyond the surface and staying focused on the change that you want to create. Good leaders compartmentalise rejection, push forward when told no and keep going. Move on quickly and try again.”

Jasper Smith

Founder of Arksen, a company making vessels, adventure apparel and overland vehicles based in the Isle of Wight

20.

Question established models

“For the first 14 years, I faced plenty of scepticism. People would say, ‘He’s not a pilot – he’s an asset-finance guy! What’s he doing here?’ But I didn’t want to learn the industry’s way of doing things because I wasn’t happy with it. I wanted to fix what wasn’t working. It needed a fresh set of eyes to help it completely change and offer something that would deliver exactly what users wanted. I had to trust my instincts.”

Thomas Flohr

Founder and chairman of Vista, a leading global private aviation company

Illustrator —— Michael Parkin

Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

1.

Roberto Rocha and Germán Losada

Co-founders,Vemo, Mexico City

“The first time that we met one of our investors, he said, ‘You either have the best electric-mobility model that I have ever seen or you’re totally crazy,” says Roberto Rocha, Vemo’s co-founder and CEO, sitting in a ninth-floor office in Mexico City’s Polanco neighbourhood. If the past few years are anything to go by – Vemo recently raised $63m (€56m) for further expansion – it’s safe to say that the company falls into the former category. “We have proven that we have the winning formula for a market such as Mexico,” says Rocha.

Opposite him sits Germán Losada, his Argentine co-founder and chairman. The former investment bankers founded their mobility start-up in 2021. Noticing that the take-up of electric vehicles (EVs) in Mexico was low, they hit upon their clean-mobility idea. A core part of their business is an EV lease-to-buy programme called Vemo Impulso for ride-hailing drivers who can’t afford to buy cars right away. “We provide leasing to people who are typically not taken care of by the traditional banks because they don’t have good credit histories,” says Rocha.

Vemo, which partners with ride-hailing platforms Didi and Uber, has had to create both the supply and the demand, since little infrastructure existed before its arrival. It has been developing an extensive EV-charging network across the country and paying 1,600 ride-hailing drivers fixed salaries to work two shifts per day in its cars through its Vemo Conduce arm. “In the absence of [state] subsidies, for the economics to work, we required significant utilisation,” says Losada. A third string in Vemo’s bow is operating EV fleets for businesses.

Vemo’s lease-to-own venture is now operating in five Mexican cities, while the rest of the business also expands. “Today we have the country’s largest public charging network,” says Losada. “And in terms of charging sessions, we’re the largest in Latin America.” Mexican sales of fully electric vehicles in the first four months of 2025 almost tripled year on year and Vemo sees opportunities in other Latin American nations. “We have a unique business model that’s proven to work,” says Losada.

vemovilidad.com

Steps to success

1. Build an ecosystem: Vemo realised that it needed to grow both supply and demand – and set about doing so.

2. Corner the market: It moved in an aggressive way at the beginning, acquiring four companies in the first three months.

3. Be cost efficient: The company has explored working with US EV brands but the economics don’t work for now – hence the use of Chinese models.

2.

Adrián Marfil and Juan Manuel García

Co-founders, Los Patrones, Monterrey

Furniture brand Los Patrones has been tapping the domestic market for what it does best: metal. Founded in 2015 by Adrián Marfil and Juan Manuel García, it is continually evolving. In 2021, for example, the company took control of its production process. Los Patrones has become a benchmark for metal-furniture excellence in Mexico and is eyeing expansion both at home and abroad.

Monterrey is an industrial city. How did you harness its manufacturing side?

Adrián Marfil: Most of the materials that we use are metal, which is produced here. We have taken advantage of our geographical situation.

How did you end up taking over your factory?

Juan Manuel García: At the beginning, our provider was my father’s company. In that post-pandemic period of sluggishness, he suggested that we absorb it, along with all of the employees.

How are you evolving?

AM: We’re developing stainless steel for gardens and swimming pools, which would allow us to work better with hotels and other big projects. Then we want to look at e-commerce and retail sales.

Do you see yourselves as entrepreneurs?

JMG: We saw an opportunity and we took it – the perfect definition of entrepreneurship. The factory is part of the muscle but the heart and soul of the brand is the design.

lospatrones.mx

3.

Maye Ruiz

Founder, Maye, San Miguel de Allende

When interior designer Maye Ruiz moved from Mexico City to the town of San Miguel de Allende in her home state of Guanajuato, she was initially concerned that being away from the epicentre of art and design would hinder her career. But the move – which was prompted by her desire to be with her husband, Daniel Valero, the founder of artisan-focused studio Mestiz – gave her the chance to get out of the CDMX bubble. “It is really refreshing,” she says.

In 2021, Ruiz established design studio Maye, which unabashedly embraces bold colours. “What matters most is working with people who bring a unique sensitivity and a strong creative drive,” she says. Her workplace, on a cobbled street near the centre of town, exemplifies her distinctive style. Visitors enter through a primary-blue steel door into a tranquil courtyard, where windows are framed in the same vivid hue. The bathroom and kitchen, meanwhile, are lined with ruby-red tiles.

“My style works really well in San Miguel de Allende,” says Ruiz. Many of her clients own multiple residences worldwide, which makes them more adventurous in their design choices. “They’re bold about colour here,” says Ruiz. Because the city is famously vibrant, with streets fringed with houses in shades of peach and pink, it’s easy to break away from beige.

Beyond residential projects, Ruiz has ventured into commercial design. Notably, she collaborated with her husband on the restaurant at Casa Arca hotel in San Miguel de Allende. Located in the historic Casa Cohen, it features Ruiz’s playful décor, including large woven lampshades.

Having firmly established herself in the city, Ruiz now aims to grow and diversify her business beyond Mexico and expand into product development. “We are always looking to partner with people and brands that share our vision and push us creatively,” she says. But she has no intention of straying from her new base. “Mexico City is such a vibrant city with so many things to do but it can also be really distracting,” she says. Being in San Miguel de Allende presents a unique opportunity to grow her practice. “It’s a place where you can focus on your business.”

maye.mx

4.

Luis González and Ana Holschneider

Founders, Cervecería Hercules and Caralarga, Querétaro

“I’m restless and have my own ideas,” says Luis González, the co-founder of Hércules brewery, a glass of sour beer in hand. His wife, Ana Holschneider, who is sitting beside him at a beer-garden table in Santiago de Querétaro, agrees. “He’s always talking about the next project,” she says. González and Holschneider, who met in Mexico City and have four children, are entrepreneurs in every sense – even though Holschneider says that they established their careers “without knowing it” and González confesses that he has never put together a business plan. It all started 14 years ago when, after a stint in Hong Kong, the couple moved to Santiago de Querétaro to take over part of a half-abandoned textile factory that belonged to González’s family.

Eyeing the beautiful factory buildings dating back to 1846 – as well as the grand hacienda attached to it – González saw potential and undertook an impressive renovation project with his twin brother, Carlos. The first step was to establish Cervecería Hércules, an independent craft brewery in a country dominated by big groups. “We saw the chance to make a quality beer in Mexico with profound brewing values,” he says.

In step with González, Holschneider started a design studio called Caralarga, influenced

by pre-Hispanic Mexico. Having previously experimented with silk and pearls, she hit upon the idea of using the threads from the Querétaro textile factory. “I walked around the factory and saw the leftovers, which looked like queso Oaxaca [a stringy cheese],” she says. “I said, ‘If we can make jewellery from this thread, it will be spectacular.’”

The couple have come a long way. Caralarga, which employs 50 people, has moved into making large wall-hangings for collectors and interior designers across the globe. Cervecería Hércules, meanwhile, has invested in expanding its capacity. Alongside the two brewery bars – and organising concerts, film screenings and dance classes at the Hércules site – it has opened a beer hall in Santiago de Querétaro, as well as a restaurant and a shop in Mexico City. “We don’t want to open something just to open it,” say González.

The latest piece of the puzzle has been Hotel Hércules, which launched in July 2023 in the former hacienda. It has 40 rooms with a mid-century aesthetic and wall hangings from Caralarga. Holschneider and González aren’t finished yet. “I never thought that all of this would happen to me,” says Holschneider.

almacenhercules.mx; caralarga.com.mx

Steps to success

1. Give back: Former textile workers and residents get discounts on beer.

2. Deliver something fresh: Querétaro previously lacked a gathering space that offered so much. Identify local needs.

3. Have the right people: Holschneider’s business partner, Ariadna García, and artisan María del Socorro Gasca are key, as are Udo Muchow (García’s partner), friend Santiago Migoya and brother Carlos for González.

Five more entrepreneurs to watch

1. Juan José Gutiérrez

CEO, Jelp Delivery, Tijuana: Logistics solutions software for last-mile delivery.

2. Montserrat Messeguer

CEO, Montserrat Messeguer, Mexico City: Making boots inspired by the north of Mexico since 2017.

3. Mario Ballesteros

Founder, Ballista, San Miguel de Allende: Curator and former magazine editor Ballesteros runs a platform for art and homeware.

4. José García Torres

Investor, Mérida: The gallerist is an investor in Mérida ventures Salón Gallos and Pizza Neo.

5. Laura Noriega

Founder, Tributo, Guadalajara: Design company from Jalisco’s capital that uses artisans from across the country.

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

- Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

- Eight ideas for Mexican businesses that are ripe for the taking

- Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

- The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene

- Oaxaca Aerospace’s Mexican-built plane has beaten the odds and is ready for takeoff

Three offices so beautiful you’ll want to apply to work in them

From offices in mixed-use developments to intimate ateliers, a workplace’s form and function can influence employee morale, foster collaboration and enhance the perception of a brand. Here we profile three distinct spaces showing how thoughtful design elevates business quality and output.

1.

The Workshop by Ministry of Design

Singapore

Room to experiment

When planning its big office move in 2024, Singaporean interiors-and-branding firm Ministry of Design (MOD) saw a chance to redefine its way of working. A diverse team across multiple Asian cities, along with the rise of video conferencing and virtual whiteboarding technologies, led MOD founder Colin Seah to consider how the office can foster better work culture. “There was a real need for a creative collaboration space, where you could connect with one another and touch and feel the materials you were using,” he says. With that, The Workshop was born.

A compact, high-ceilinged space in Singapore’s Jalan Besar neighbourhood, its interiors are defined by three-dimensional metal scaffolding. The majority of The Workshop is dedicated to teamwork, anchored by a long, counter-height table that’s flanked by a magnetic pinboard and TV on one side and superbly arranged boxes of samples, swatches and reference books on the other.

Every detail has been tailored by Seah. “The temperature of the lighting can be adjusted to reflect different environments,” he says. “The magnetic board allows us to quickly stick items to project spatial renders. The countertop isn’t in jet black or a stark white, which might affect colour perception.”

In short, it’s an environment that facilitates creativity and spontaneity, by making both teamwork and experimentation easy.

2.

1516 W Carroll Ave by Converge Architecture

Chicago

Space to gather

1516 W Carroll Ave in Chicago’s West Loop neighbourhood is a 1920s-era warehouse recently reworked by Converge Architecture. It now accommodates a rooftop farm, film studio, test kitchens, private dining and events areas, offices and a ground-floor coffee shop, retail space and restaurant.

Yet Converge Architecture principal Lynsey Sorrell doesn’t draw her greatest satisfaction from the exposed columns, brickwork patina or the greenhouse gables that now prick the horizon. “I’m most proud of the way that we managed to get our clients to work together,” says the architect, whose initial client for the project was urban-agriculture venture The Roof Crop. Its founder and creative director, Tracy Boychuk, invited restaurant Maxwells Trading and test kitchen and studio Flashpoint Innovation to take up co-tenancy to create a culinary hub.

Sorrell and her colleagues found ways to create space for each venture by strengthening the building’s structure, raising the roofline, adding both indoor and outdoor floor space and fitting wooden soundproofing baffles to the ceilings. The result brings together a nine-to-five desk-space with seasonal urban agriculture and an open-all-hours approach to contemporary hospitality.

“If you’re working in hospitality, sustainability or city farming, you really need partners,” says Sorrell. In Chicago, there isn’t a building that brings them together quite like this one.

3.

Salt by Thiss Studio

London

Good relationships

For design-focused communications agency Salt, finding a studio to do the interior fit-out of its office meant turning to one of its own clients. The company’s founding director, Celeste Bolte, asked local architecture firm Thiss Studio to deliver a space that could be used for desk work, photoshoots and meetings during the day and events in the evening. The brief also came with the request to prioritise repurposed materials.

“We sourced items together and talked about how we could be creative with the budget through salvaging and reuse,” says Tamsin Hanke, co-founder and director at Thiss Studio. “If you’re meeting clients at your office, the space becomes an external presentation of who you are as a company.”

The open-plan, 55 sq m office features high ceilings, large windows and steel beams remnants from its former industrial life. Salt added a white linen curtain to demarcate areas. “We wanted a place that was adaptable,” says fellow Thiss Studio co-founder and director Sash Scott.

The firm also designed furniture made from existing on-site and second-hand materials. The office’s location in east London meant joining forces with local workshops. A carpenter across the road helped to cut the cabinets and a signpost that hangs outside the office. “It’s a project borne of good relationship-building,” adds Scott.

Businesses we’d back: Eight ideas for Mexico that are ripe for the taking

As Latin America’s second-largest economy, Mexico has the expertise, population and market conditions to help your next venture succeed. We highlight some areas that are wide open for business.

1.

Manufacturing: Automotive

A car maker to get the region moving

Mexico has a long track record of making cars. Often that has meant foreign brands setting up plants in the north from which to export to the huge US market across the border. Given the country’s expertise and wealth of engineers, there is surely room for a viable Mexican motor brand that could service Latin America and, one day, export further afield. It could take inspiration from the Volkswagen Beetle that is beloved by Mexican drivers. And while its entry-level car would run on petrol, a “Made in Mexico” electric version could spotlight the country’s hi-tech manufacturing skills. This year has already seen the arrival of Mexico’s first e-bus, from exporter Megaflux and manufacturer Dina.

2.

Services: Animal wellness

A standout in pet care

About 70 per cent of Mexican households have a pet and the industry is ripe for start-ups. The country might already have websites such as Pasea Perros, which finds dog walkers for owners as far afield as Campeche and Chiapas but there’s still an untapped market – whether it’s for a line-up of chihuahua-inspired grooming products or a treats brand that draws on Mexican speciality ingredients (see US start-up Wagwell, which has taken a big bite out of the market). There are also opportunities for an online-driven pet daycare service or a new breed of veterinary service. Los Angeles brand Modern Animal provides a successful model: offering pet pampering in a well-designed, trustworthy setting would quickly get tails wagging.

3.

Hospitality: Restaurants

A chain of tasty, stylish bistros

Mexico has its fair share of star chefs, from trailblazer Enrique Olvera to fêted names such as Edo López, Lucho Martínez and Elena Reygadas. We would happily invest in a well-priced restaurant group that faithfully represents the country’s 31 states and capital, with outposts dotted around a few key cities and beach resorts across Mexico. The concept would be to reintroduce forgotten flavours from the regions to the country, with a view to a potential global roll-out. As for the look? Mexico has no shortage of graphic-design talent to work on the visual identity. For international inspiration, we like the style of Jack’s Wife Freda, whose playful aesthetics can be seen in its five outposts in New York.

4.

Transport: Traffic management

A company to shift cities up a gear

There have been recent mobility breakthroughs but what about a private company that could raise funds, offer consultancy services and work with municipalities to create greener town centres and reduce traffic? While we salute public transport initiatives such as Mexico City’s Cablebús gondola, it’s not solving the mess on the ground. Our plucky new start-up would assist existing mobility companies, look for new shared transit options, help implement traffic calming and improve bike-sharing infrastructure. From Nuevo León to Veracruz, regions are sprawling with urban growth and there’s a pressing need for some smart thinking to help keep cities moving.

5.

Cosmetics: Make-up

A new face in the beauty world

As consumer spending rises, the beauty market is poised and ready. Native brands, such as Xinú perfumery, have distinguished themselves by creating distinctive bricks-and-mortar experiences. But there’s an opening for other Mexican brands nationally, in the rest of North America and beyond. With readily available natural ingredients, such as prickly pear, cactus, tepezcohuite and blue agave, the stage is set for glowing success.

6.

Beverages: Soft drinks

A healthy hydrator with a touch of fizz

Mexican Coke, which is made with real cane sugar, not corn syrup as it is in the US, is sought after far beyond the shores of Sayulita. But there’s an opportunity for healthy drinks from an independent maker too. We would love to see a range of organic drinks that draw on local herbs and flavours. Some upstart brands are already getting in on the action: take Oasis and its Club Suero electrolyte drink, which debuted earlier this year and features limes from Veracruz, agave syrup and salt. Our bubbly brew would take inspiration from the timeless label design of Monterrey’s Topo Chico.

7.

Retail: Stationery

A shop to write home about

Mexico’s metropolises need a top-notch stationery shop in the vein of London’s Present & Correct or Milan’s Fratelli Bonvini – a place to get postcards and writing paper, and stock up on pens and notebooks. It would carry the best stationery from Germany to Japan and champion emerging Mexican brands. Mexico already has spots such as OfficeMax for work supplies and Papelería Lumen for art paraphernalia – but it’s missing a place to casually linger in. It would feature plenty of beautiful wrapping paper, much of it incorporating Mexican design and motifs – and, of course, a dedicated gift-wrapping service.

8.

Defence: Arms and aerospace

A regional security champion

Mexico’s defence sector has the potential to boom, given its proximity to the vast US market. The Mexican government clearly feels the same – earlier this year the country’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, opened the sixth edition of the capital’s aerospace fair, Famex. The fledgling Latin American and Caribbean Space Agency is based in the country too. The government is looking to push technological independence and develop “Made in Mexico” through its Plan México, including funding a range of smes. There is room for companies to make everything from whole planes to components, given that areas such as turbine production are growing. New players shouldn’t look to compete with the likes of the US, UK, Israel, Germany or Japan. Nascent plane maker Oaxaca Aerospace knows that well. Instead, they should focus on offering competitive prices that developing countries might be interested in.

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

- Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

- Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

- Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

- The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene

- Oaxaca Aerospace’s Mexican-built plane has beaten the odds and is ready for takeoff

Abidjan is one of Africa’s most dynamic cities. But can it swerve political instability?

“Cocoa is a jewel,” says Ivorian chocolatier Axel Emmanuel Gbaou, holding up a pod that he has just split with his machete. Its glistening white pulp conceals the brown beans that have long been the economic bedrock of Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s biggest cocoa producer. Gbaou is guiding Monocle around a lush plantation just a few hours’ drive from Abidjan, the country’s former capital and largest city. All around us, coffee plants and lemon and guava trees shoot up from the fertile ground. “We have a saying in Côte d’Ivoire: everything can grow here.”

There’s a consensus among people who regularly travel into Abidjan that the best day to do so is Sunday because, as the usual bumper-to-bumper traffic relents, the air on the bridges across the Ébrié Lagoon fills with the aroma of toasted cocoa, rising up from the industrial zone. But the sweet smell of success isn’t just emanating from the city’s many roasting factories. Most people who are thriving in today’s Côte d’Ivoire are concentrated in this 6.3 million strong metropolis, where building sites are always within view and opportunities never far away. These days, Abidjan’s rooftop bars are packed, the champagne flows in its many nightclubs and property prices in some neighbourhoods rival those in Western European cities. In sectors from hospitality and construction to banking, a boom is under way that has transformed the country from a conflict-ridden basket case to an economic powerhouse, a beacon of dynamism in a part of the world not famed for such things. En route from Paris, the Business Class cabin on Monocle’s Air France flight stretches back 20 rows, with almost every seat taken. Abidjan is one of only 10 destinations served by the airline’s prestigious La Première service – a testament to the wealth flowing into the city.

Antoine Abou Khalil, the operations manager of boutique hotel La Maison Palmier in Abidjan’s leafy Cocody neighbourhood, was drawn here from Beirut by the promise of economic opportunity. Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the first post-independence president of Côte d’Ivoire, encouraged arrivals from Lebanon in the 1960s, hoping to draw some of the Levantine nation’s famed business acumen. During the 2006 war between Lebanon and Israel, the Ivorian government granted Lebanese citizens visa-free passage. Today, this 80,000-strong community, mostly Ivorian nationals of Lebanese descent, plays an outsized role in Abidjan’s booming economy. Marcory, a neighbourhood known as “Little Beirut”, is packed with hotels, shops and new apartment buildings. It is one of the city’s hottest areas for property development, with about a dozen major construction projects in progress.

Among the businesses that are helping to reshape the Marcory skyline is French firm Architecturestudio, which opened an Abidjan office in 2023. Monocle hops aboard a buck hoist to tour the rooftop of one of its current projects, the Golden Tulip Akwaba hotel, which is under construction. “The rooftop pool here will offer the best view of the lagoon in all of Marcory – and perhaps all of Abidjan,” says Enzo Coicadain, a Frenchman who recently transferred to this city from Brussels.

A few blocks away, La Tour F, which is set to become Africa’s tallest skyscraper when it is completed next year, glimmers in the midday heat. The tower symbolises not only the construction sector’s growing clout but also Abidjan’s status as a regional powerhouse.

Côte d’Ivoire’s economic data tells a story of vertiginous ascent. From 2012 to 2019, the country’s real GDP growth averaged at more than 8 per cent per year and it has not dropped below 6 per cent since the height of the coronavirus pandemic. Unemployment stands at about 2 per cent (against a West African average of 12 per cent) and median income has nearly doubled, making the government’s aim to reach upper-middle-income status by 2030 seem increasingly achievable. Abidjan has become a magnet not only for foreign investors but also for members of the Ivorian diaspora returning home to start businesses – people known as “repats”. Buoyed by remarkable improvements in infrastructure and a tax-code overhaul that brought the country in line with international standards, Côte d’Ivoire rose 59 places up the World Bank’s “Ease of Doing Business” index between 2011 and 2020.

“The first factor that explains our upward trajectory is the sociopolitical stability that followed 2011,” says Stéphane Aka‑Anghui, the executive director of Côte d’Ivoire’s largest employers’ federation. That was the year when Alassane Ouattara became president. Aka Anghui, an eloquent, bespectacled former civil servant, believes that Ouattara, a former deputy director at the IMF, is largely responsible for the country’s economic revival. “We are neither Soviet nor Chinese,” he says. “But under President Ouattara, we have revived the practice of having a national business plan and that has paid off.”

One sector where this policy is bearing fruit is in the processing of cashews. Côte d’Ivoire produces about 1.2 million tonnes of the nut per year, which represents about 40 per cent of the global supply. To make the most of this natural bounty, the government took out a $200m (€170m) World Bank loan in 2018 to fund tax rebates and priority access to cashew crops for businesses that process the nuts locally, adding tens of thousands of jobs to Côte d’Ivoire’s economy.

The career of Cynthia Niamoutié, who runs Cilagri Cajou, the largest Ivorian‑owned cashew-processing plant, is proof that the plan has worked. “We were producing 1,500 tonnes of processed nuts in 2019; this year we’re planning for 20,000,” she says, as she gives Monocle a tour of her factory, which employs more than 350 people and occupies warehouses near Abidjan’s port. From those at the steaming vats, where the processing of the raw cashews begins, to the sorting tables at which dexterous workers flick the nuts into containers at improbable speed, Niamoutié seems to know every employee by name, asking questions and providing instructions.

“Eight years ago, this place was just a parking lot,” says Niamoutié, whose father used it as a car administrative procedures site. Until 2018, three years after her father started Cilagri Cajou, Niamoutié lived in Houston, Texas. She is one of the many repats who have returned home over the past 10 years, seeking to play a part in their country’s economic resurgence.

Though Monocle met many others like Niamoutié over the course of our four days in Abidjan, there is little hard data on repats. In a 2022 report on Ivorian migration, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development stressed that it was “crucial that data-collection tools be deployed” to measure the phenomenon – which is significant enough that there is now an annual forum dedicated to repats, with hundreds of officials, investors and businesses attending. The patron of next year’s event, to be held in Abidjan in February, will be Côte d’Ivoire’s influential first lady, Dominique Ouattara.

Most of the repats who we speak to tell us that they returned after a stint working or studying in the US. That was the case for Régis Bamba, co-founder of Djamo, a digital bank that has become one of West Africa’s most successful fintech start-ups. Monocle meets Bamba at Djamo’s offices in the Zone 4 district of Marcory. “It was while I was studying computer science in the US that I connected with many other members of the African diaspora,” he says. “Since then I have felt that I want to build something for Africa.”

A native of Abidjan who first returned home in 2011 after the end of the second Ivorian civil war, Bamba wears a white shirt and Ray-Bans with built-in cameras, which ensure that no highlight of his day goes unshared with his social-media followers. “The banking-adoption rate [in Côte d’Ivoire] was only 20 per cent among the adult population not so long ago,” says Bamba in one of Djamo HQ’s glassy meeting rooms, each of which is named after an African capital city. “We thought that we could do something that works better.”

On a continent where a visit to a bank branch typically means long lines and tedious paperwork, many rely on mobile-payment systems such as M-Pesa and Orange Money for easy access to the financial system. Djamo gives users access to a card to pay online and offline, a transfer wallet, vaults to save money automatically and an investment account. In Abidjan, its customers draw directly from their bank accounts to pay the many street vendors who only take mobile money. Its convenience has made the app a huge hit and caught the eye of Silicon Valley incubator Y Combinator, which invested in 2021.

“You have stability in Côte d’Ivoire, which means that people aren’t afraid that their investment will just disappear,” says Bamba. “Jobs are being created, people here are consuming more stuff and they feel comfortable spending money.”

Nowhere is this economic dynamism more evident than at the Ivoire Trade Center (ITC), a vast commercial complex built in the shadow of the historic Hotel Ivoire. Its upper floors, completed in 2021, house the offices of multinational corporations such as Deloitte and PwC, while a shopping centre with pristine white floors welcomes well-heeled customers at ground level.

In the ITC’s food court, which is furnished with modernist-inspired pieces, the most popular destination is Africafé, a casual dining spot that offers speciality African coffee alongside comfort food from across the continent. “I wanted to adapt the classic European coffee shop to Africa,” says its founder, Djeneba Keita, who dreams of turning Africafé, which recently opened a second outpost in Abidjan, into “the African Starbucks”.

Monocle meets Keita over a lunch of chicken breast with attiéké, a cassava-pulp dish that is a staple of Ivorian cuisine. As we eat and chat, she gets up every so often to greet a regular or embrace an employee. She is originally from Mali and used to run a small catering business from her home. Five years after her launch in Abidjan, she is eyeing expansion abroad.

“The step now is how to scale it,” she says. “How do I get to Paris, New York and Tokyo?” Keita is building her success on a customer base that didn’t exist in Côte d’Ivoire 10 years ago – a growing class of professionals with the disposable income to dine out, as well as corporate types in need of a hip spot for informal meetings and presentations.

Next to Africafé is ABY Concept, another business catering to the same kind of clientele. Its terracotta-hued space, designed by Ivorian architect Issa Diabaté, showcases clothing by dozens of independent African labels. Some of the pieces on sale cost upwards of €1,000.