The Entrepreneurs

Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

Mexico City is buzzing with energy, fuelled by a population that, over the past five years, has grown by about 700,000 to reach 22.5 million. Tourism is booming too, surpassing pre-pandemic peaks. This surge in residents and visitors has sent demand for housing, office space, restaurants and retail into overdrive, keeping developers and architects on their toes. Here we highlight three entrepreneurs who are doing things a little differently.

1.

Best for: The high life

Meir Lobatón Corona

Glance at Mexico City’s skyline and you’ll see clusters of reflective buildings. “They don’t make sense in this temperature,” says architect and developer Meir Lobatón Corona. Mirrored buildings might work in cities such as New York but not here, where the temperature is relatively mild.

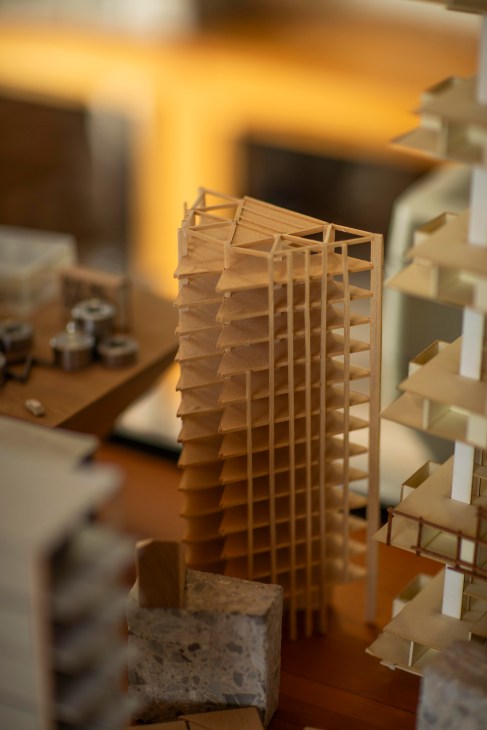

Monocle is visiting Torre Gutenberg, a recently completed 13-floor office tower in Anzures, two blocks away from Chapultepec Park, designed as a flexible structure. When tenants take occupancy of a floor, they move into a cement-and-glass shell that’s designed to be transformed over time and can be repurposed as an apartment or hotel room. “We thought, ‘Since we’re going to build it, let’s make it last’,” says Lobatón Corona. “The only way to do this was by building it as a structure, not as an office tower.”

From inside Torre Gutenberg, where the look is softened by travertine floors and oak panels, you can see the entire city unfolding before you. “It’s completely transparent,” says Lobatón Corona. Unlike many contemporary office towers, these spaces aren’t temperature-controlled grey boxes. Every floor has a large balcony with big glass doors and windows that allow air and light to flood in.

Torre Gutenberg is a well-ventilated, bright space that will hopefully be as relevant in 50 years’ time as it is today. “We’re starting to understand that we don’t have to innovate just for the sake of doing something new,” says its designer.

Barrio to watch: Escandón

Wedged between Condesa and San Pedro de los Pinos, Escandón offers easy access to the city centre.

Prices

A two-bed flat costs between MX$6.5m and MX$6.7m (€296,000 to €305,000) on average.

Local finds: Sorbo

The area’s smallest wine bar, with the laid-back atmosphere of a Sicilian enoteca.

Ingenieros 41, Miguel Hidalgo, 11800

2.

Best for: Rethinking the office

Andrés Martínez, Iterativa

When Andrés Martínez, a co-founder of Iterativa, discovered an office building on Reforma Avenue that had stood empty during the pandemic, he decided to bring it back to life. Iterativa partnered with an investment fund, which took over the lease, and then set about redeveloping it. Today it houses offices and a restaurant and nightclub, as well as co-working space Público.

Iterativa doesn’t completely own the buildings that it works on. “We find the opportunity, execute the project and operate it,” says Martínez. Alongside co-working spaces, the company is rolling out hotels and serviced apartments to meet the demand for housing and accommodation in Mexico City. When Monocle meets him in the Reforma 333 building, he shows us around the businesses that now occupy the former office block.

Público, which has big grey couches and glass windows that look out at the city’s Angel of Independence, was designed to be a hub where creatives could collaborate. “Instead of following the WeWork recipe of creating a huge common area and little spaces, we spread out the communal areas in different parts of the building,” says Martínez. Despite it being a towering office block, he was adamant about giving it personality. “We wanted to design the building [like a] house, to create something much more natural where people can meet.”

3.

Best for: Adaptive reuse

Rodrigo Rivero Borrell, Reurbano

Developer Reurbano has a well-earned reputation for breathing new life into Mexico City’s historic buildings through adaptive reuse and urban regeneration. And in a city that’s peppered with architectural gems awaiting restoration, there has been no shortage of structures for the firm to work with.

When Monocle meets Rodrigo Rivero Borrell, founder and CEO of Reurbano, on the edge of the leafy Condesa neighbourhood, he whizzes us around the ground level of Zamora 15, a mixed-use space that, when completed, will also have 20 apartments. When he purchased the 80-year-old buildings in 2014, they had been abandoned for more than 25 years. Today Zamora 15 houses not only his brick-clad office but also an array of tenants who are all young entrepreneurs.

For Rivero Borrell, the choice of renters is integral. If there isn’t enough variety, “you lose a lot of the value,” he says. At a building that he developed in Roma, Reurbano welcomed tenants such as Eno, a restaurant chain popular with local residents, but also kept a grocer who had been in the building for years.

“The grocer is very important to the community,” says Rivero Borrell. “When you see what these people who belong to a community contribute to their area, you realise just how much good you can do by keeping them there.”

And while fostering a sense of locality and belonging is good for residents, the grocer’s presence also makes sense financially. “You cannot imagine how much a well-selected commercial space on the ground floor increases the value of the properties,” says Rivero Borrell.

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

- Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

- Eight ideas for Mexican businesses that are ripe for the taking

- Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

- The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene

- Oaxaca Aerospace’s Mexican-built plane has beaten the odds and is ready for takeoff

How Ukranian startup Himera built a war-ready radio during a blackout

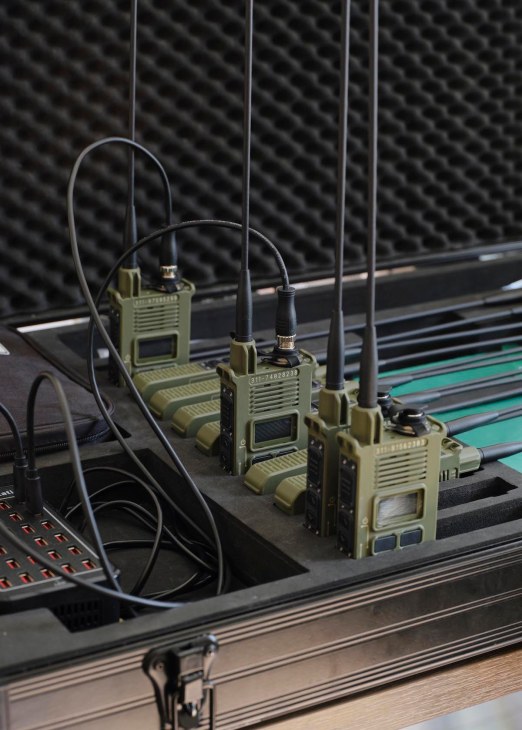

It was in 2022, during the Russian advance on Kyiv, that the founders of walkie-talkie maker Himera realised that modern communication systems weren’t up to scratch. “One of [my friends] was in Ukraine’s territorial defence forces and he had first-hand experience of the total lack of communication solutions,” says co-founder Misha Rudominski. “Commercial options can be detected or disrupted. Having reliable, resilient communication is key.”

Drawing on their prior experience in hardware start-ups and consumer electronics, Rudominski and his co-founders hatched a plan: Himera would create radio and communication devices that were cheap to make and the production of which could easily be scaled up. The most important upgrade? They would be resistant to electronic warfare – the jamming and intercepting of signals between devices, which is used to disrupt all sorts of defence capabilities, from surveillance to navigation and battlefield communications.

It wasn’t an easy time to start a business. Attacks on infrastructure were a regular occurrence and the available labour force dwindled as Ukrainians fled or signed up to fight. “There was a constant need for new solutions because at that time we lacked everything,” says Rudominski. “It was very much a bottom-up approach – we just needed to get the product into the hands of the users.”

There were some advantages to the situation. “Often manufacturers don’t know how their products are performing,” he says. “But I’m in touch with hundreds of users, including those on the battlefield. They can tell me about issues that they’re experiencing and we’ll work on a solution straight away.” In three years, Himera’s products have had more than 80 updates. One example is the G1, a handheld radio that lets soldiers talk to each other and has an operating temperature range from minus 20c to 50c and a range of 2km.

Today, the radios are in use by Ukrainian marines, intelligence forces, special operations and more. This success has sparked wider interest: in 2024, the US Air Force bought Himera’s radios for testing by and in early 2025 the company partnered with Ottawa-based data-protection firm Quantropi to integrate better encryption. It will also distribute Himera’s products in the US, Canada and select Nato markets. The Ukrainian market isn’t profitable, but Rudominski takes a long view. “We’ll earn our money later selling the best tactical radios and communication solutions to customers worldwide.”

Grabbing a table at food court P – the new cafeteria offering global fare in Futako-Tamagawa

It’s just before midday and lunch service is in full swing at the curiously named P food court in Tokyo’s Futako-Tamagawa area. Salarymen tuck into smash burgers as two old friends catch up over a glass of wine. Perched at the main counter are a mother and daughter, surveying the crowd with pizza slices in hand. Though P (the letter stands for “Public”) has only been open since April, lively scenes such as these have become a daily sight.

Owned by department-store company Takashimaya, Toshin Development has been deeply entwined with this area since it was founded in 1963. While department stores remain key players in Japanese retail, they need to stay nimble. The development of Takashimaya’s West Building – which the P food court occupies, alongside retailers and car parks – is an example of a successful attempt to keep things fresh.

“About 40 or 50 years ago, there were ground-floor restaurants here and people who lived nearby would come to have a casual meal,” says Koichi Moriwaki of Toshin Development. “But they were eventually turned into fashion boutiques. Until recently, this street was lined with the shops of big brands such as Celine, Fendi and Gucci. These had quite a limited audience and, over time, the links to the local area were lost.”

Seeking to re-establish these connections and, in the process, bring the area back to life, Toshin approached 39-year-old art director Takahiro Yasuda to oversee the project. “We viewed this as an opportunity to attract the next generation of customers: people in their thirties seeking a sense of community and an eye-to-eye relationship with businesses,” adds Moriwaki. This proved an ideal brief for Yasuda, whose clients have included the likes of Convenience Wear, Nike and Hasami-based ceramics brand Maruhiro.

“As we began considering ways to renew the street, I thought about how to make it somewhere that people would want to walk down again,” says Yasuda, who collaborated on the project with Daisuke Motogi, the founder of architecture practice DDAA. “One day, Motogi said, ‘Why don’t we turn the entire pavement into a park?’” The interior design soon began to take shape. The façade was set back two metres and landscaped seating areas created, while the glass frontage and materials blurred the lines between inside and out.

Yasuda developed a visual identity that’s bold and symbolic with a hint of fun, working equally well on street signs and seasonal posters. At the same time, Motogi’s design incorporated marble wall panels repurposed as tabletops, Karimoku New Standard stools made from insect-damaged timber and Okinawan soil, which was used to colour the main counter. “The space has been designed to provide all kinds of options, from seating styles to locations, allowing it to be enjoyed in countless ways – like a park or plaza,” says Motogi.

This philosophy extends to the food options on offer, overseen by Max Houtzager, who previously worked on Parklet and Meiji Park Market near the Tokyo Olympic Stadium. Sensing an opportunity to bring small-to-mid-sized operators with a slightly higher price point to the area, Houtzager gathered together a trio from the independent food scene to accompany a miniature version of his Ikejiri Ohashi-based restaurant, Massif.

Every operator brings a strong identity and its own loyal following to P – which was part of the plan. The mix of familiar favourites and limited menus adds to the destination’s appeal, while ensuring that there’s something for everyone. Pizza Slice makes and bakes eight different New York-style pizzas; Nepalese restaurant Adicurry serves up samosas, chai and more; Danish brewer Mikkeller pairs beer with burgers; and Mini Massif caters to all occasions with café fare, noodles and wine. Collaboration has been key to the food hall’s success, particularly since the unconventional design places three shops side by side in the central island. “It comes down to the people,” says Houtzager. “Everyone is in it together.”

The project is in its early stages but is already catching the eye of operators, restaurants and customers. It will continue to evolve, with DDAA working on interventions to enhance navigation, flow and customer experience. Here’s hoping that the food court succeeds in its aim to be a catalyst for other similarly sociable places around Futako-Tamagawa.

p.ublic.jp

Deep foundations

Tamagawa Takashimaya Shopping Center opened in 1969, inspired by a new wave of shops and department stores emerging across the globe at the time. It was Tamagawa-based Toshin Development’s first project. In the decades since, the development has grown to encompass multiple sites, turning former factories into green-fringed commercial facilities and creating cobblestone laneways lined with restaurants, aiming to nurture the after-dark dining scene.

Futako-Tamagawa address book

A 15-minute train ride from Shibuya, Futako-Tamagawa is part of the Japanese capital but feels like an upscale commuter town, thanks to its green spaces and the nearby Tama river. It’s also a bustling commercial hub, with Takashimaya’s first “suburban” department store, Tokyu’s expansive mixed-use development Futako-Tamagawa Rise and the HQ of Japanese technology conglomerate Rakuten Group all in the area. Here are few things to see while you’re here:

1.

Tsutaya Electrics

store.tsite.jp

2.

Let It Be Coffee

3-23-25 Tamagawa

3.

New Valley wine shop

newvalley.base.shop

4.

Nishikawa Seika-ten

(for handmade sweets)

3-23-29 Tamagawa

The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene

José Noé Suro isn’t one to rest on his laurels. The lawyer-turned-arts entrepreneur is responsible for almost single-handedly transforming Guadalajara, Mexico’s second city, into an international arts hub – but he isn’t finished yet. Last year, Suro and collector Nidia Elorriaga opened Plataforma, a beautifully restored art space in Guadalajara’s Colonia Americana district that transcends the building’s gloomy origins as a funeral home. The project was conceived as a launchpad for emerging talent, with the gallery dedicating an entire floor to residency studios for new talent. “It’s my gift to the city,” says Suro.

On paper, the capital of Jalisco state has long had all of the ingredients for artistic success. It is graced with a wealth of beautiful modernist buildings, the legacy of architect Luis Barragán, who was born here; rents are more affordable than in the capital with ample studio space available; and the landscape has an abundance of natural materials including clay, wood and agave. A manufacturing hub for electronics and technology, Guadalajara has developed a small but dedicated local collector base. It wasn’t until Suro took an interest, however, that the scene took shape.

An art lover with a sizeable private collection, Suro joined his family ceramics business, Cerámica Suro, in 1993. The firm, whose history dates back more than 70 years, found a second wind under his stewardship, ramping up its production facilities to create dinnerware for hotels, as well as kitting out restaurants by Mexican super-chef Enrique Olvera and Noma’s René Redzepi in Copenhagen. Meanwhile, commissions for tiles have come from as far afield as French brand Hermès and the Guggenheim Museum in New York. A household name in his native city, Suro was resolute that Cerámica Suro needed to be more than just profitable it would serve as a catalyst for a broader arts ecosystem too.

“People don’t come to Guadalajara to see a Tracey Emin show,” he says, guiding monocle around the airy modernist premises of Plataforma. “They come to see art made here.” Funded by the largest pharmaceutical company in Latin America, the space is proof that Suro’s dedication to promoting domestic art over the past three decades is coming to fruition.

Other local entrepreneurs are capitalising on the attention Suro has brought to Guadalajara. Apto Galería, which opened in 2023, is housed in a former textiles factory in one of the city’s oldest neighbourhoods.

“Nurturing long-term relationships with artists, collectors, institutions and the public is as important for the lifespan of our gallery as funding,” says co-founder, Florencia Pardo. “We collaborate with artists who might not yet have gallery representation.”

Apto Galería aims to make Mexican contemporary art more visible internationally, while helping it to remain rooted in the identity of its home country. It has so far worked with more than 50 multidisciplinary artists, both Mexican and international, who have offered interpretations of Guadalajara through painting, sculpture and drawing.

Independent arts space Espacio Cabeza and Guadalajara 90210 – which presents work in unlikely locations, from rooftops to construction sites – are invested in making the city a vital node on the international art map. “There’s no point waiting for public institutions to step in,” says Marco Valtierra, Espacio Cabeza’s artistic director, as he gives Monocle a tour of the space, a former 1930s residence, where their Lo Visible show included a room filled with smoke and flickering light bulbs. “We’re interested in breaking with convention. It’s easier to experiment with perceptions of what art is in Guadalajara because the stakes are lower,” says Valtierra.

From the outset, Suro was intent on nurturing artistic talent in the city and has hosted a residency programme in the premises of Cerámica Suro for the past 25 years. It has supported more than 600 artists specialising in ceramics, metalwork and glasswork. (Alumni include Canadian Marcel Dzama, Cuban-American sculptor Jorge Pardo and US painter Jeffrey Gibson.) Cerámica Suro generously sponsors them, providing them with materials and a space in which to work.

“In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, artists left this city as soon as they could,” says Suro. “Now they see it as a strategic advantage to return.” The enterprise is mutually beneficial. When alumni return home, they take Suro’s name – and brand Guadalajara – with them overseas.

To retain visiting international talent, Suro, with his artist friends, established Premaco art fair (now known as GDL Art WKND) in 2019. It is positioned as the warm-up act to Zonamaco, Latin America’s leading contemporary art fair, held in Mexico City (CDMX) since 2002. Suro’s factory – and latterly Plataforma – opens for four days a year when international artists and buyers are already in the region, maximising spending potential.

Guadalajara is proof that persistence and entrepreneurship can create a scene from scratch. It’s also a case study for ambitious stakeholders wanting to test a new market. Following Suro’s advice, Madrid-based gallerists Silvia Ortiz and Inés López-Quesada of commercial space Travesía Cuatro opened a contemporary-art outpost in Guadalajara in 2013, then another in CDMX six years later. Suro also persuaded a friend to lease the Arabic-style 1929 Casa Franco to Travesía Cuatro, giving it a Guadalajara landmark from which to operate. “Because of Suro, art is no longer centralised in Mexico’s capital,” says Ortiz, who regularly travels to Art Basel, Frieze Seoul and Arco Lisboa to discover new work and bring it back to Guadalajara.

No longer a creative underdog, the city’s art scene has quietly proved itself as distinct from that of CDMX. At its core, Guadalajara has a dogged entrepreneurial spirit and a cadre of artists and galleries supported by collections, fairs, collaborations and commissions.

City Hall is starting to wake up to the area’s art potential. “With Suro’s help, I want to make Guadalajara into a global reference point for art,” says the city’s mayor, Verónica Delgadillo García, who joins us at a popular cantina called De La O. “We’re in a position to make art accessible to everyone,” says Suro. “And we will never take that for granted.”

The who’s who of Mexico’s art scene

1. Zélika García: Set up Zonamaco, Latin America’s leading contemporary art fair

in 2002.

2. Sergio Romo:

Co-founded Angstroms in 2022. Based between Mexico City and Madrid, it mitigates financial hurdles for artists and galleries.

3. Baby Solís: The art critic established Obras de Arte Comentadas (ODAC), a digital platform and art collectors’ club.

4. Bianca Peregrina:

Set up Trámite in 2020, a young art-animation-focused festival in Querétaro that is a platform for contemporary and emerging art.

5. Enrique Argote: Launched Clavo art fair in Mexico City in 2021 and has welcomed galleries from cities such as Medellín and Los Angeles.

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

- Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

- Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

- Eight ideas for Mexican businesses that are ripe for the taking

- Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

- Oaxaca Aerospace’s Mexican-built plane has beaten the odds and is ready for takeoff

Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

It’s a sunny morning in central Oaxaca City and the communal table at Bodaega bakery is buzzing with customers tearing into pastries. One popular variety is a take on a Danish treat called a spandauer, adapted for its warm setting with a mango-and-passion-fruit-custard filling. This mix of Nordic and Mexican flavours makes for a pleasant surprise.

With a modest population of 715,000 people, Oaxaca City is a place where time seems to move slowly: church bells clang gently amid plazas and streets lined with old buildings. A big part of its allure is this sleepy charm and many businesses embrace it. But things are changing. In the past five years, more than 17,000 people have moved here from the US and there has been a 77 per cent jump in tourism. Hospitality entrepreneurs are catching on, opening new hotels, cafés and restaurants that combine the city’s heritage with fresh ideas.

Bodaega’s co-owner Rafael Andrés Villalobos Valderrama, who opened the café with his Danish partner, Catherine Schmidt, hadn’t intended to launch a business when he returned to his home city. The couple met in Copenhagen while Villalobos Valderrama was working at Sanchez restaurant and doing an apprenticeship at Meyers Bageri, a popular bakery chain. After moving they noticed an increase in visitors, as well as a growing appetite for international delicacies. The couple opened Bodaega three years ago. “We ‘Mexicanise’ Danish pastries,” says Villalobos Valderrama. “We take guava or passion fruit and use it in a way that makes sense for local people.” An influx of customers from abroad has also meant that they could cater to a more diverse crowd than just a few years ago.

In 2023, Mexico’s Grupo Habita unveiled Otro Oaxaca, a 16-key hotel opposite the Church of Santo Domingo de Guzmán. Designed by local firm Root Studio, its interiors feature furniture by the region’s artisans, reclaimed wood and natural materials such as red soil. This mix of old and new reflects a broader shift in Oaxaca, where entrepreneurs are expanding their footprints while taking pains to maintain the city’s cultural fabric.

When Juan Pablo Hernández moved to Oaxaca from the north of the country and opened Boulenc in 2013, he couldn’t have imagined that it would evolve into the multifaceted enterprise it is today. What began as a market stall selling sourdough bread has transformed into a diverse business encompassing a bakery, a café, a shop and two hotels. “We were investing and growing organically,” says Hernández, who expanded when more buildings on the street became available. “When you want to open a business here, there’s a social aspect you have to address,” he says, adding that he works with artisans whenever possible and sources his ingredients as locally as possible, including wheat from a nearby farm.

“The old culture here is so deep and profound,” says restaurateur Enrique Olvera, who co-founded Criollo in the centre of the city. “You need to spend time here to realise that time works differently. Hospitality is part of our DNA.” Olvera owns a string of restaurants including Pujol in Mexico City. When he opened Criollo in Oaxaca City with chef Luis Arellano almost 10 years ago, the goal was to create an experience that felt like dining in someone’s home. “What I enjoy most is going to someone’s house,” he says. “Mexican food, particularly what we eat in Oaxaca, is hard to translate to restaurants.”

This approach is evident in Criollo’s design. Guests enter through a door next to the kitchen and an open comal (a traditional flat griddle), on which tortillas are fired. They dine in an open-air pebbled courtyard that is reminiscent of a family gathering space, with chickens wandering around the tables. Olvera has also opened Casa Criollo, a two-bedroom guesthouse. Initially intended as his personal retreat during visits to Oaxaca City, the property is now available to visitors. Ironically, it’s often booked out when he’s back in town.

Dominican-born designer Javier Reyes is the founder of Rrres, a design studio that works with artisans in rural areas to develop colourful geometric rugs, throws and baskets. Last year he and his partner, Lillian Hardy, expanded by opening Landdd, a workshop space in Portland, Oregon. Reyes has grown the business in Oaxaca City too, launching a one-room guesthouse that features Rrres products. “We try to incorporate our design and vision,” he says. The guesthouse, which looks onto a small cactus-filled garden, has a sunny yellow kitchenette and is dressed with bright throws and geometric rugs. “We think of it as our studio guesthouse,” says Reyes.

On the outskirts of the city, about a 40-minute drive from the centre, is Alfonsina, a restaurant that is committed to blending tradition with innovation. It was opened by Jorge León and his mother, Doña Elvia, who can sometimes be seen pressing tortillas and cooking them on the comal. The tables in its peaceful courtyard are set under trees. From the open kitchen, homely dishes such as tamales and flame-grilled fish with mole and rice are prepared as part of a five-course menu.

The restaurant is committed to the use of locally sourced seasonal ingredients, as well as to sustainable practices such as rainwater harvesting to address the region’s water scarcity. León, who previously worked at Grupo Olvera’s Pujol in Mexico City and Cosme in New York, wants to find ecological solutions for his home city. “The restaurant industry can raise awareness and positively impact the environment,” he says. Most recently, Alfonsina launched a programme training fishermen in eco-friendly practices and supplying establishments in Oaxaca City and Mexico City.

Crudo is another good example of an entrepreneur embracing both traditional and modern sensibilities. After working in the US and Mexico City, Oaxacan-born chef Ricardo Arellano returned home five years ago to open an omakase restaurant that serves Japanese-style bites made from local ingredients. Noticing diners flooding in from the US and Canada, he saw an opportunity to expand and has since opened three bars and one more omakase counter. At the casual à la carte bar, diners are seated on wooden chairs along a narrow counter where they sip mezcal (the state’s drink of choice) and whisky cocktails flavoured with corn. They eat sashimi with pickled jícama instead of ginger. “You meet people from all over the world here,” says Arellano.

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

- Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

- Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

- Eight ideas for Mexican businesses that are ripe for the taking

- The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene

- Oaxaca Aerospace’s Mexican-built plane has beaten the odds and is ready for takeoff

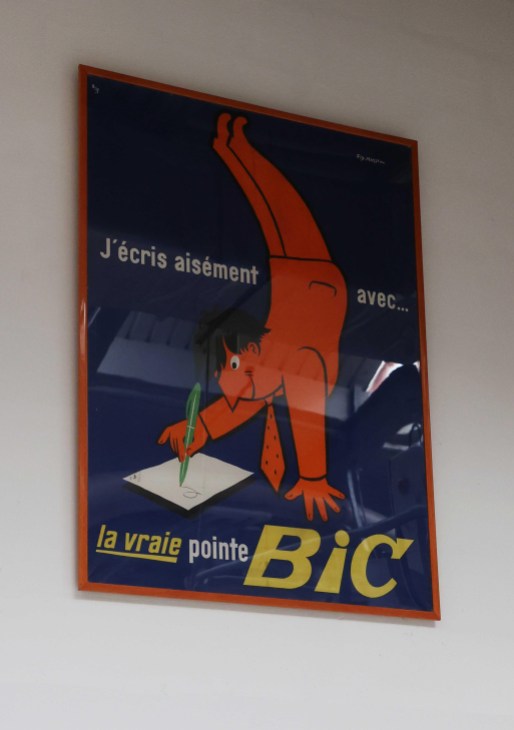

How Bic has kept the ball rolling for 75 years – and what it has planned for the future

It’s highly likely that there are several Bic pens in your house – and you almost certainly will have no idea how they got there. Perhaps you bought a box of them years ago or swiped a handful from the stationery cupboard at work. Or maybe you found them at the bottom of a tote bag that you were handed at some conference or other. It’s also possible that you possess – again by means that you no longer recall – a Bic lighter and even a few Bic razors.

The French company, founded in 1945, is a paradox. It has sold billions of its products yet no one remembers buying them. Bic biros in particular have become a sort of collective possession. Most people wouldn’t think twice about picking up one of someone else’s; few would much care if theirs was swiped.

“One of the cool things about representing this brand is that I am with our consumers all day long,” says Gonzalve Bich, Bic’s 46-year-old CEO. “People will get up in the morning and shave with our razor. And then they will use our pen at work. Maybe when they get back home, they’ll light a scented candle with our lighter.”

Bich meets Monocle at the London offices of Tangle Teezer, a hairbrush manufacturer that Bic acquired late in 2024 for €200m. Bich sees it as a congruent addition to a line-up of brands known for simple yet elegant everyday items. Also among Bic’s current portfolio are lines of stationery, digital notebooks and temporary tattoos (Bic Sport, its windsurfing offshoot, was sold in 2019).

In some respects, it’s surprising that Bic has survived, let alone prospered. Developments in technology, fashion and society over the past couple of decades almost resemble a conspiracy to destroy the company: keyboards supplanting pens; beards coming back in style, slicing razor sales; the number of smokers falling, reducing demand for lighters. But the company has weathered evolving habits through its strategy of fiercely protecting the brand while selectively expanding its offering.

Bich, whose father oversaw the family firm from 1993 to 2006, has been its CEO since 2018. When he steps down later this year, his successor probably won’t be a Bich – but the company has had leaders from outside the family before. Bic was founded in 1944 by his Italian-French grandfather Marcel Bich, who bought the patent for the ballpoint pen from a Hungarian inventor called László Bíró. (The fact that both of their names have become synonymous with that invention attests to their success.) Marcel was the beau ideal of the eccentric European aristocrat: an heir to an obscure baronetcy who collected art, ordered his shoes from Church’s in Northampton and enjoyed 12-metre yacht racing, underwriting several unsuccessful attempts to win the America’s Cup.

As Bich tells it, his grandfather refused to accept that cheap, everyday products couldn’t be stylish. “He was obsessed with design, form and function,” says the CEO. “He was very much of the philosophy that perfection is when you can’t take anything more away, rather than asking, ‘How much can we add?’ I think that we still stand for that idea. The original Bic Cristal pen remains one of our bestsellers 80 years later.”

Like other Bic products, the Cristal pen is still made in France, at least for European consumers. Though the company now manufactures on five continents, it considers its Frenchness to be crucial. Bic’s HQ looks out on Boulevard Périphérique, a ring road in the Paris suburb of Clichy. Monocle is given a tour of the site by Clémence, the premises co-ordinator, who previously worked on the factory floor in the ink and cartridge workshop. Raw materials enter the facility at its southern end; finished, boxed-up pens exit at its north. Around the complex, we frequently spot the company’s cartoon avatar, Bic Boy: a schoolchild with a nib for a head, designed in the 1960s by Raymond Savignac. Bic boasts that it makes 25.4 million products every day across the globe. Watch the digital display atop a machine tracking how many red-ink Bic Cristals are being cranked out and this claim becomes eminently believable. The shift today began at 06.30. It is a tick after 11.00 and 44,723 more red Bic Cristals are on their way out into the world, possibly to terrorise the essays of the lackadaisical students of 44,723 weary teachers. (A Bic Cristal, assuming that you don’t lose it, will write for 3km. That’s a lot of statements to the effect of, “Disappointing… See me after class.”)

It is mesmerising to witness the precision and complexity involved in the manufacture of everyday items that will barely be spared a second thought once they leave here. The ball in the top of a Bic pen is made from tungsten carbide, which is polished with diamond paste and powder to give it its shape. To demonstrate how dense the 1.2 millimetre balls are, a Bic technician passes around a small milk-carton-like bottle containing about 500,000 of them. It is only half-full but weighs almost 2.4kg.

Each of these balls will soon be mounted in a brass nib and connected to the plastic tube that holds the pen’s ink. This tubing is extruded in a single length through metal trenches of cooling water at 200 metres per minute – so fast that Monocle can’t see the translucent material moving – before being sliced to pen length by a furiously whirring blade.

Some of the machinery is designed and built in-house. “It’s something that we feel strongly about,” says Clémence. “When you have an idea, it’s better to do it yourself.” Quality control stations put randomly selected components to work, cranking out spirograph-style patterns to ensure that all of the pens are working as they should. On one such station, there’s a picture of Bic Boy scrutinising a nib through a magnifying glass.

These days the idea of a “disposable” plastic product seems less like a beguilingly modernist selling point than a crime against the environment. Back at Tangle Teezer in London, Bich tells Monocle about Bic’s move towards recyclable products and packaging. In the past five years, he says, the company has gone from using 20 per cent recycled, reusable or compostable packing materials to 85 per cent – and is aiming for 100 per cent. “But we can only do that when it doesn’t affect the quality or technical characteristics of the product,” he says. “You don’t want the barrel of the pen snapping in half because we have used some kind of substandard recycled plastic.”

When Bich became Bic’s CEO, the company was grinding through what was, by its standards, a low ebb. Its 2017 annual report described, with an almost audible wince, “A Challenging Year with Unprecedented Levels of Volatility”. “Things were still working,” says Bich. “But they weren’t working quite as well as they had been. There’s that optimisation curve: once you go past it, things start getting painful and we were there.”

So Bich implemented “Horizon”, the first global strategic plan in Bic’s history. “We told our team, ‘You’re no longer just a maker and brand of pens. You’re a human expression company,’” he says. That meant diversifying, with forays into other products such as digital notebooks. “We opened up what we should be working on and what problems we should be solving for the consumer.”

Corporate history, however, is strewn with the carcasses of much-loved brands that, dissatisfied with the customers they had, chased after others who proved illusory. “That’s fair,” says Bich. “But if the consumer says, ‘This is just a commoditised product and I don’t care about brand A or brand B, or how it feels,’ then you have lost that battle. As long as you’re still the best-loved brand and most recognisable product, you can put it in Lagos, São Paulo, Tokyo, New York or wherever you want.”

After leaving Bic, Bich plans to concentrate on the foundation that he has launched to support families that, like his own, are contending with the challenges facing children with autism. “It will be about sharing experiences and perspectives, always with the goal of strengthening the family unit and ultimately the community,” he says, “It will yield better outcomes for everyone involved.”

Nevertheless, he sounds sorry to be departing and closes our interview with some advice that he would like to share with his successor.“Always respect the past,” he says. “Those things that made the tree strong, the nutrients in the soil in which the roots are buried, the flowers around the tree – cherish them and make them grow. And follow your intuition. You have to deal with data when you’re running an organisation this big – I have terabytes of it to look at and all sorts of experts to consult – but at the end of the day humans are the ones who make the ultimate choices. Investment A or investment B? Packaging colour A or packaging colour B? Trusting your instincts over the long term as a leader is incredibly important.”

bic.com

1988

Launch of the short-lived Bic perfume, which ceases production in 1991.

1990

Launch of a range of decorated lighters, joined the following year by Bic’s first electronic lighter.

1992

Bic purchases the US correction product Wite-Out to help its pen users correct their mistakes.

1994

French launch of the Bic Twin Lady bi-blade, a razor aimed at women, in pastel shades.

1997

Bic consolidates the correction product market by buying Tipp-Ex.

2001

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York adds the Bic Cristal to its permanent collection (the Bic Maxi lighter follows in 2005).

2004

Launch of the Bic Soleil razor for women and the Bic 3 – a triple-bladed implement – for men.

2017

Launch of Ubicuity, a collection of outdoor furniture made from recycled pens through a partner called Plas Eco.

2018

Launch of temporary tattoo marker BodyMark. (Four years later, Bic acquires Canada’s Inkbox and US decal brand Tattly.)

2019

Launch of Made for You, Bic’s first gender-neutral razor.

Three entrepreneurs who switched careers after being inspired by something in their kitchens

1.

Leon Foo

Singapore

Singaporean entrepreneur Leon Foo left behind a career in accountancy to found his roastery, PPP Coffee, in 2009. But that wasn’t the end of his journey. “In 2018 I discovered how controlling the temperature, pressure and solubility of a coffee machine would create an opportunity to transpose features from a £15,000 industrial machine into a £300 capsule one,” says Foo.

This led to the launch of the Morning Machine in 2018. The Nespresso-capsule-compatible contraption allows users to control the temperature, pressure and water-to-coffee ratio through an app. “We are still one of the very few companies that are laser-focused on coffee drinkers looking for convenience,” he says.

Last year, Foo followed up the Morning Machine with the Morning Dream, which helps home brewers froth café-grade milk with precision. “We hope to become the Spotify of the coffee world. Just like how the streaming platform connects artists to listeners, we hope to connect roasters with coffee drinkers.”

drinkmorning.com

2.

Shiza Shahid

USA

In 2012, Pakistani entrepreneur Shiza Shahid and Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai founded the Malala Fund, which lobbied for funding for young women to access education, especially in countries where there are significant barriers. Shahid’s next solution was to a more domestic issue. Upon migrating to the US at the age of 18, she found an outdated kitchenware industry in which items were riddled with toxic chemicals. She launched cookware brand Our Place in 2019 alongside her husband, Amir Tehrani.

“At the time, the kitchenware industry felt exclusive – we leaned into inclusivity,” says Shahid, who wanted her brand’s imagery to show the product in kitchens with more realistic, messier dishes. She was determined to prove that the kitchenware industry didn’t need to rely on sometimes toxic PFAs (chemicals widely used for their grease-resistant properties). “Our Place holds more than 200 patents but much of the sector is still doing things the old way,” she says.

Its next foray is into kitchen appliances. “The UK market loves air fryers but most are made from plastic and coated in Teflon,” says Shahid. Her version is made from stainless steel and glass and uses a patented, non-toxic Thermakind coating.

fromourplace.co.uk

3.

Gen Terao

Japan

Rock musician-turned-entrepreneur Gen Terao founded home appliance brand Balmuda in 2003. “We realised that many kitchen appliances were just made for convenience,” he says. Tokyo-based Terao wanted to create something stylish as well as functional. Among a line-up that includes coffee makers and hot plates, the bestselling product is the much-copied toaster (two million sold and counting), which steams bread with precise temperature control to achieve a crispy exterior and a soft, pillowy interior.

Terao is more inspired by his travels than by market research. “I see my music career as fundamentally the same as my work in kitchenware,” he says. “In my time as a musician, my perspective shifted. I moved from wanting to be the most popular hitmaker to aspiring to build a company that could genuinely contribute to people’s lives.

Whether I’m holding a guitar or a screwdriver, these are tools that allow me to create something meaningful.” The toaster has been given a reboot this autumn, with better temperature control for perfect crunchiness, while the design “keeps the essence of the current toaster with a little more elegance”.

How streaming platform Deezer is striking a chord with music fans – and fighting AI in the process

On a spring evening in Paris, more than 300 twentysomethings are packed inside the striking headquarters of the French Communist Party, designed in the mid-1960s by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer. Despite the setting, this is no political gathering. The modernist Espace Niemeyer has been transformed for the night into a concert venue for premium subscribers of French streaming platform Deezer. Parisian rapper Franglish, who is due to play a sold-out show at a 20,000-seat stadium later in the week, lights up the stage in this far more intimate setting with his blend of rap, R&B and pop. At times, his voice is drowned out by fans singing almost every lyric in unison.

As frustration grows with Swedish platform Spotify’s algorithm-driven playlists and controversial royalties model – which critics accuse of short-changing musicians – Deezer, founded in 2007, is pursuing a different path. Under its CEO, Alexis Lanternier, the Paris-based company is doubling down on what it calls an “artist-centric” strategy: prioritising fair compensation for artists, fighting AI-generated music fraud and offering live events that connect artists with listeners.

“Users want more meaningful connections and physical experiences are usually what leave a mark,” says Lanternier, sitting in his office overlooking a quiet square near Moulin Rouge. “Music streaming platforms offer the same catalogue so the difference lies in how we position ourselves and what features we offer.”

With just 10 million paying subscribers, Deezer is far smaller than Spotify, Apple Music or Amazon Music, which have 268 million, 93 million and 80 million subscribers respectively. But it’s betting that intimacy, ethical payment policies and emotional connection can win where scale cannot. Though Deezer has expanded into countries including Brazil, Germany and South Africa, it still relies heavily on France for its subscriber base and partnerships with domestic telecom providers. The company’s largest backer since 2016 has been British-American businessman Leonard Blavatnik’s holding company Access Industries; Orange and the billionaire Pinault family are also among its key investors.

Lanternier, who joined in September, arrived in time to announce a significant milestone: Deezer had a positive free cash flow for the first time. “It’s an amazing moment because we now have room for long-term thinking,” he says. “We spend a lot of time talking to our users, especially those from younger generations. What we’re seeing is that music streaming has not evolved quickly enough in the past 10 years to meet their needs.”

Deezer’s strategy involves rewarding artists who its subscribers actively support. Its “artist-centric” model seeks to compensate musicians based on genuine engagement, unlike the dominant “market-centric” system, in which royalties are pooled and distributed based on total streams. Under the latter system, which heavily favours big-name acts, even if a subscriber listens to more esoteric artists, most of their monthly fee goes to the chart-toppers. This has the effect of sidelining independent musicians and niche genres. To address this imbalance, Deezer signed a deal with Universal Music in 2023 to double royalties for artists with at least 1,000 monthly streams from a minimum of 500 unique listeners. A similar agreement followed in January with France’s Society of Authors, Composers and Publishers of Music.

These deals also seek to tackle the growing problem of “fake” music. The rapid rise of generative AI has already triggered a wave of lawsuits. Last year a man in the US was arrested and charged with allegedly using AI tools to create thousands of fake songs and stream them billions of times using automated bots, claiming more than $10m (€8.8m) in royalty payments. According to Deezer, about 18 per cent of songs uploaded on its platform – more than 20,000 tracks per day – are now fully generated by AI. “Fighting against fraud is another way of maximising artist remuneration. That’s a big thing,” says Lanternier.

While Spotify has reportedly promoted so-called “ghost artists” on popular playlists to reduce its royalty payouts, Deezer has developed a cutting-edge detection tool to filter AI-generated tracks from algorithmic recommendations. “We are the only industry where you have just a few platforms that have the power to stop this kind of thing from happening,” says Lanternier. “And we [at Deezer] are the ones who are doing something about it.”

Technology has changed the way that many of us listen to music – and not always in a good way. With much of the world’s song library at our fingertips, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. To help users “take back control” from the algorithm, Deezer is launching a series of features to help people to customise their listening experience more effectively. These include a dislike button for songs or artists and a history of recommended tracks that users can edit to reflect their current preferences. “You might see a recommendation and think, ‘That was me two months ago but I don’t feel like that any more,’” says Lanternier. “Increasing transparency about how the algorithm works is a major focus for us.”

While Spotify and other platforms have poured resources into podcasts and audiobooks, Deezer has chosen to stay focused on music, hoping that this will help to deliver a more personal, emotionally resonant experience. The exclusive concerts for premium subscribers in Paris are a part of this. “It’s important for us to humanise our app,” says Azzedine Fall, Deezer’s director of music and culture, raising his voice above the noise of the crowd at the Franglish show. “Our essential role is as an intermediary – and that’s what we’re doing here tonight. We’re bringing fans closer to the music and making the brand as human and as tangible as possible.”

Deezer has a long way to go before it can pose a real threat to its Swedish rival. But on a local level, it’s not just users who seem to appreciate its approach. “These days you get tonnes of content on social media but sometimes you lose real connection,” says Franglish, reflecting on his performance a few weeks later. “Deezer is trying to bring that back. That’s a pleasure because it’s why we make music in the first place.”

Marseille’s historic grape juice kiosk is pressing ahead once more

Marseillais entrepreneur Yannis Amokreze shelved his day job in fashion and set out to save his family’s grape-juice kiosk near Vieux Port in 2022. Once a mainstay of the Occitanie diet, jus de raisin was long touted as a healthy alternative to wine that could help to detoxify the liver – but the thirst for the drink dried up after the advent of mass-produced juices in the 1950s. Today, thanks to an increasingly health-conscious customer market and a rising demand for alcohol-free beverages, Station Uvale du Palais is pressing ahead and turning a profit. The family business, which was established in 1943 by a cousin of Amokreze’s uncle Eugène, is the only survivor of the area’s original eight stations uvales.

“I often welcome three generations from the same family,” he says. “ The elders come to honour a childhood memory, while the younger people discover something new.” The entrepreneur has maintained the profitability of his kiosk by favouring short distribution channels and working with seasonal fruit from local growers. Amokreze also takes a very personal approach. “For more than 40 years my family has worked with Jacques Daussant, a grape supplier based in Vaucluse,” he tells Monocle. The former president of the now defunct Fédération Française des Stations Uvales, Daussant was the original supplier for several of the country’s kiosks.

During high season, Amokreze visits Daussant’s vineyards every week to harvest the grapes that he presses by hand. “It’s an artisanal economy on a human scale,” he says, his pink-stained hands hinting at the morning’s graft. “It’s intense, absorbing work.”

Benefitting from mineral-rich soils and the warm Mediterranean climate, Amokreze harvests the region’s black muscat, white chasselas, Alphonse-Lavallée and cardinal grapes between August and October to create his jus de raisin. But the third-generation owner of Station Uvale du Palais also has an eye on modernising the Marseillais tradition. So he also presses melons, peaches, oranges, lemons, pineapples and grapefruit, expanding the kiosk’s business potential as people increasingly seek out alternatives to the sugary stuff found in supermarkets.

Served from a welcoming, green wooden kiosk, Amokreze’s juice isn’t an endeavour to scale then flip. He is determined to maintain the personability of service that his aunt and uncle worked hard to create. “You don’t only come to drink juice,” he says. “You come to share a moment at the counter.”

Does the future of fashion start with these six new materials?

Many in the fashion sector are determined to do better for the environment. The future of materials presents a major opportunity on this frontier – creating fabrics that can be produced without using the dyes or chemicals that pollute waterways. It’s also about crafting clothes that are hardy enough to go the distance and remain objects of value season after season – instead of contributing to the tonnes of textile waste that end up in landfills every year.

1.

Ventile

Developed in Manchester during the Second World War to keep pilots warm and dry if they ended up in the sea, Ventile is an admittedly vintage innovation – indeed, it was used in outerwear worn by the first climbers to scale Everest. Yet the hardy waterproof material is now remaking the world of wet-weather gear. In 2017, Swiss textile firm Stotz & Co acquired the Ventile brand, giving it a new lease of life. The material is enjoying a stylish renaissance: it’s now more commonly found on the catwalk than in combat situations.

According to Daniel Odermatt, Stotz & Co’s brand director, Ventile’s big sell is that it is waterproof without relying on harmful “forever chemicals”, or PFAs. Woven from long-staple organic cotton, its fibres pull tightly together when it comes into contact with water, keeping moisture out. Though polluting, PFAs were historically the industry standard and were used in a wide range of waterproof outdoor clothing, including in popular materials such as Gore-tex. Now, though, the tide is turning: in the past year, several US states have banned their use in consumer goods and the EU has signalled plans to roll out similar measures. Brands are looking for alternatives.

As a result, demand for Ventile has soared in recent years, says Odermatt from his office overlooking the Limmat river in Zürich. “In 2023, Stone Island wanted a technical fabric in all-natural fibres. So it came to us.”

While Ventile is still used for limited runs of British and Swedish military immersion suits, the order book is now dominated by fashion brands. Lemaire, CP Company, A Kind of Guise and Loewe have all featured the material in their recent outerwear collections.

Though a mid-20th-century invention, Ventile still seems surprisingly ahead of the curve. To demonstrate its waterproofing credentials, Odermatt shows monocle two large containers stacked on top of each other; the one above is full of water, while the one below is empty. A sliver of Ventile fabric separates the two. “The fibre swells roughly 10 per cent so it gets waterproof,” he says. Though the material creates an effective barrier for water droplets, it also offers an impressive degree of breathability. Odermatt pumps air into the bottom container and Monocle watches as bubbles pass up through the Ventile and into the water above.

There’s still a big hurdle for many brands, says Odermatt: the cost. The process of making Ventile involves the use of expensive cotton and a laborious manufacturing timeline that includes weaving in northern Italy and dyeing in northern Bavaria. Odermatt says that he would consider some Asian manufacturing further down the line.

For now, however, Ventile is a proudly European product. “We are the benchmark,” says Odermatt. The transformation of its fortunes is indicative of European fashion brands’ restless search for materials that can give them an edge over the competition.

2.

Cozterra

Developed by Singaporean materials company Xinterra, Cozterra is a fabric treatment that sequesters carbon dioxide from the air. Twenty T-shirts embedded with Cozterra can capture the same amount of carbon dioxide as a mature tree in a single day; the carbon is then converted into a harmless substance when the tops are washed. Clients include Singaporean activewear label Zoda and Brazilian clothing brand Malwee.

cozterra.com

3.

Eco Nasi

Made in Kenya from pineapple waste, Eco Nasi is a sustainable alternative to leather that has the look and feel of the real thing without the need for water-intensive, carbon-emitting treatments. Founded by Kenyan entrepreneur Olivia Okinyi, the Nairobi-based company makes good use of the natural abundance of hard-wearing cellulose in pineapples.

econasi.com

4.

Solea

From Madrid-based textile innovator Pyratex, Solea is a series of cotton fabrics that offers an important upside for European buyers: every strand is traceable to its point of origin on the continent. With strict EU regulations on tracking water use and labour conditions, clients are assured that the Spanish fabrics are made from cotton grown near Seville and comply with Europe’s high standards.

pyratex.com

5.

RCO100

Catering to fashion brands including Alexander McQueen and Vivienne Westwood, Swiss company Säntis Textiles has developed a machine named RCO100 to recycle cotton waste into yarns with the durability and feel of premium virgin cotton. Cutting out the use of chemicals, fresh cotton production and the need for water, the yarn can be used for canvas, denim, twills and more.

saentis-textiles.com

6.

Desserto cactus leather

Retaining leather’s patina and strength, the humble cactus is the base for Mexican entrepreneurs Adrián López Velarde and Marte Cázarez’s vegan leather, Desserto. Thanks to the dry conditions in which cacti grow, the textile is sustainable, humidity resistant and has few inconsistencies in the grain, earning it attention from the likes of Adidas, BMW and LVMH.

desserto.com.mx