The Entrepreneurs

How one fax led to Jaime Daez building the Philippines’ fastest-growing bookstore

Jaime Daez didn’t have much of a business plan when he started selling books: he just wanted to buy copies of Spanish architecture magazine El Croquis (and, if possible, at a discount). Daez had started reading the publication as a student at the University of Navarra in Pamplona; after returning home to the Philippines in 1994 he was keen to keep collecting issues. “Amazon was nonexistent back then,” he says. “One day I decided to send the publishers of El Croquis a fax, presenting myself as a possible distributor,” he says. To his surprise, the magazine’s team agreed to give him 60 per cent off the retail price if he ordered 100 copies. Two sheets of fax paper later, Daez was a fledgling magazine and book distributor.

Sitting in his office inside the Fully Booked shop in Manila’s Bonifacio Global City (BGC) neighbourhood, Daez tells Monocle that he started off more like a door-to-door salesman than a conventional distributor. “I would flick through the Yellow Pages, looking for architecture firms and interior-design agencies to sell to,” he says. “The bigger the font, the better, because that meant they probably had a bigger budget for buying books.” His approach was simple. He would call a company and then visit its offices in person, with the hefty copies of El Croquis in tow.

Four months into his improvised career, Daez secured an appointment with a renowned Filipino architecture firm. He arrived at its building only to discover that there was a power cut – a frequent occurrence in the country in the 1990s. The lifts were out of action and the firm’s office was all the way up on the 19th floor. So Daez trudged up the stairs, carrying more than 20kg of titles; half an hour later he was still only on the 10th floor. Huffing and puffing, he suddenly realised that, because of the blackout, the architecture firm’s office was probably closed. “I tucked the box of magazines in a corner and ran up to the 19th floor,” he says. “There was no one up there.”. For Daez, this moment was a turning point. “The incident made me ask myself, ‘Am I willing to put up with all of this?’” Despite the frustrating experience, he realised that he was.

Daez’s next step was to use half of his mother’s 30 sq m sweetshop to sell an expanded range of titles focusing on tropical, Asian and Mediterranean architecture. Sales were encouraging. Eventually he took over the entire shop, widening its selection to include business and children’s books, as well as fiction. In 1997, Daez opened his first official bookshop in Glorietta, a shopping centre in the Makati precinct (Fully Booked now occupies a bigger site in the same complex). This was followed by a series of openings across Manila.

Despite his swift success, that moment of clarity in the stuffy staircase as a 24-year-old continued to play an outsized role in Daez’s career. It steeled him as the Philippines’ publishing industry faced a succession of difficult challenges, from the 1997 Asian financial crisis to the rise of e-books. “Within the span of about three years in the late 2000s, the use of e-books increased by almost 10 times,” he says. “I remember thinking, ‘I might be out of business soon.’”

Despite the uncertainty, Daez went on to take his biggest business gamble: securing a 15-year land lease to build a four-storey bookshop in the then-underdeveloped BGC precinct. “The head of [shopping-centre chain] Ayala Malls asked me, ‘Jaime, are you sure? Don’t you want to be conservative and focus on two floors first?’” But Daez believed that having his own land parcel would anchor the business in stormy times; he also suspected that BGC would soon become the new city centre. So he went all in. His instincts proved correct: today, BGC is one of the Philippines’ leading central business and lifestyle districts, the port of call for all of the biggest brands. Here, Fully Booked BGC stands as a beacon for book lovers. It’s an attractive flagship shop with plenty of natural light, a big acrylic painting by US artist Mike Stilkey that uses discarded books as its canvas and whimsical paper sculptures of marine animals that hang from the ceiling.

By 2020, Fully Booked had 31 thriving bookshops across the city but lacked a strong online presence. This became a big problem when the coronavirus pandemic forced all of Fully Booked’s shops – which the authorities deemed as non-essential businesses – to close for two months. No one was permitted to enter. “Our online sales were only 1.5 per cent of our total revenue at the time,” says Daez. “It was a matter of survival. I told my managers to bring home their laptops and encode every single book for our online shop.” Despite the lockdown, his team upped its productivity and added 10,000 titles to the business’s website within four months.

This agile response to the crisis made all the difference and cemented Fully Booked’s position as the Philippines’ go-to bookshop chain. Its biggest competitor, National Book Store, seems to have shifted its focus towards textbooks and office supplies. “National Book Store used to be a temple of the written word,” says Ric Gindap, co-founder of rising Manila-based magazine shop Spruce Gallery. “But stepping inside today, you feel like you’re preparing for a third-grade science fair, rather than feeding your literary soul.” By contrast, Fully Booked has continued to diversify its selection of fiction titles, art books, graphic novels and more.

The company’s growth looks good on paper too. Since the pandemic, Fully Booked’s online business has grown by 2,400 per cent and 17 new shops were added during the same period. Its e-commerce operation has been such a success that it has caught the eye of US publishing giant Penguin Random House. “Its executive vice-president told me that we were its case study in Asia because no one had pivoted better and more quickly than we had,” says Daez.

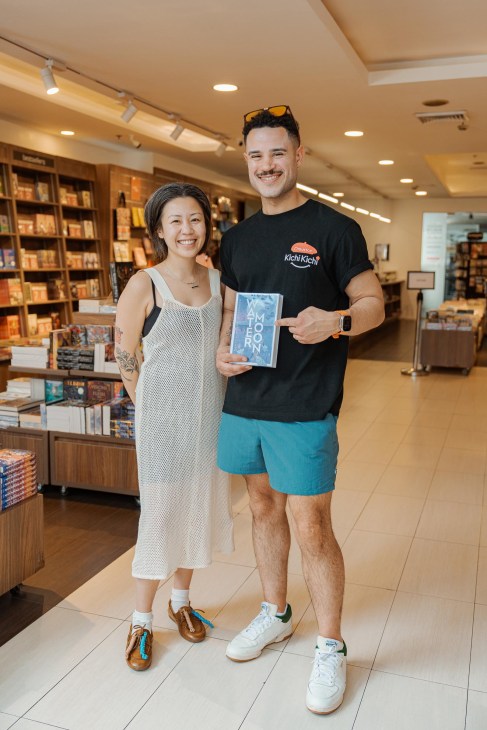

The biggest endorsement came when Japanese bookshop Kinokuniya chose to team up with Fully Booked for its expansion into the Philippines in 2022. Together they opened a co-branded shop in the Mitsukoshi BGC shopping mall, with a selection of 20,000 Japanese books. The move has enabled Daez to tap into the growth of manga (and Japanese pop culture in general) in the Philippines. “Manga exploded during the coronavirus years and Japan is unsurprisingly the top destination visited by Filipinos,” he says. It’s a partnership that is blooming. In October, Daez will be opening another co-branded shop with Tokyo matcha café Wasachi in the upscale Rockwell neighbourhood.

Fully Booked has bucked the trend of bookshop closures because Daez has always found a way to evolve with the times. While books are the foundation of the business, Daez isn’t afraid to expand its offering. He recently set aside a section for “blind boxes” – sealed packages that each contain a randomly chosen product from a wider series, such as a key-ring doll. These might seem like a departure from books but Daez thinks of this hugely popular trend as a crossover. “Many of these blind-box characters originated from books,” he says. “People come in with the intention of buying one of these boxes but might also pick up a book along the way. We’re not selling something random, like Christmas lights.”

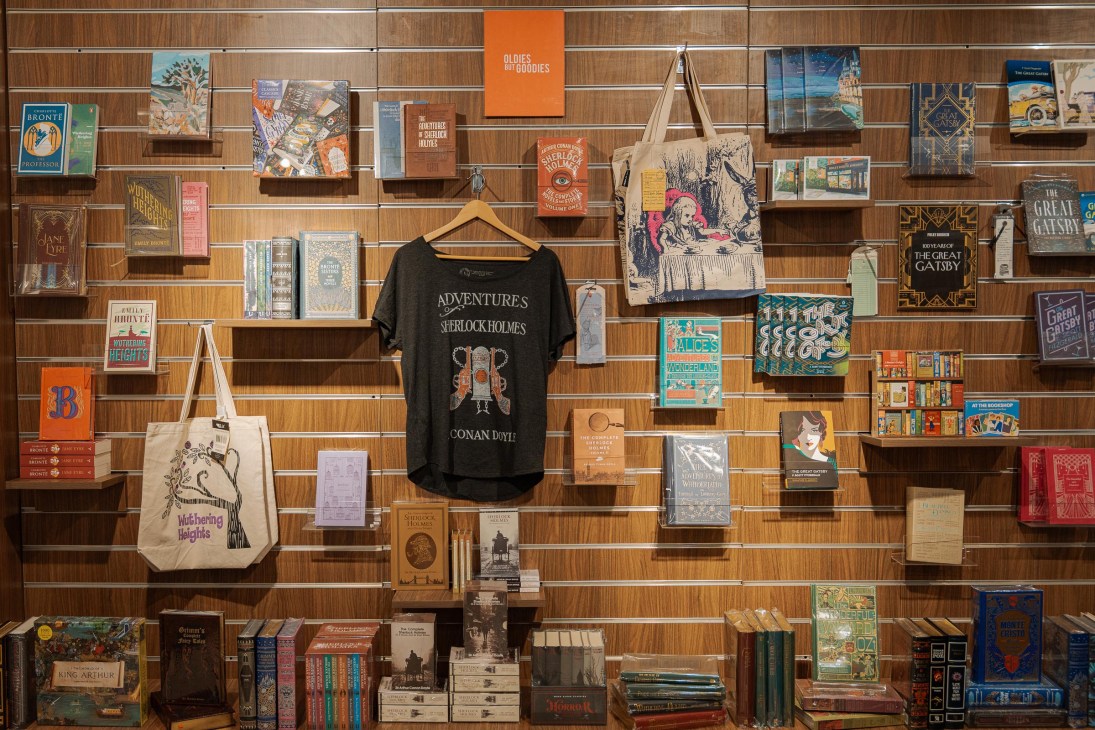

Daez is already plotting his next move: creating a suite of Fully Booked-branded merchandise. To him, the gold standard is New York bookshop The Strand, whose own branded wares are almost as well loved as the books on display. “Its shop sells so many variations of its own tote bags, T-shirts, socks and more,” says Daez.

It has been almost 30 years since that fateful fax but Daez’s zeal for what he does remains undiminished. “I put in more time working now than when I started the business,” he says. While his strategies continue to shift according to the market, there’s one constant: his love of books. “I’m a bit of a romantic when it comes to my business,” he says. “I believe that if you have passion for what you do, it can be felt in your stores.”

The CV

1994: Returns to Manila from Pamplona, Spain

1996: Starts distributing copies of El Croquis

1997: Opens his first full-fledged bookshop in Glorietta

2007: Opens the Fully Booked BGC flagship shop

2021: Fully Booked’s e-commerce business rapidly grows

2022: Inks partnership with Kinokuniya

2025: Fully Booked is on track to have 49 shops by the end of the year

Bristell Aircraft’s smooth ride from passion project to global player

About 15 years ago, Czech aircraft designer Milan Bristela saw a significant jump in the maximum speed at which small planes could travel. “But when I saw the pilots getting out of these aircraft, they would be complaining about back pain,” he says. “We realised that there was no plane on the market that was providing a speedy and comfortable ride. So we decided to focus on the ergonomics and spaciousness of the cockpit to make people feel more relaxed and safe.”

Leaving his corporate job in 2007, Milan teamed up with his son, Martin, and went on to found their own business, Bristell, to address this gap in the market. “At first, the idea was really just to build a few aeroplanes a year,” Martin tells Monocle. “We thought that it would basically be about playing with this idea – and that it would be our job, yes, but also our hobby.”

But what began as a passion project in a small, rented workshop space has become Bristell, one of the world’s premium lightweight aircraft manufacturers. Employing about 140 engineers, designers and mechanics, it now has an impressive production floor in a 10,000 sq m factory in southeastern Czechia where aircraft are built from scratch.

The company produces more than 110 two-seater planes composed of lightweight aluminium per year. The aircraft pass through a complex process of welding and assembling before being fitted with engines in a cavernous hangar. The finished planes are dispatched to customers in countries from the US to Germany, for training pilots or as private aircraft for customers looking to crisscross long distances with ease.

“Every day, when I come into work, I take a walk through the factory to see what everyone is up to,” Milan tells Monocle. “My son and I developed every plane that is being constructed here as a prototype. We know exactly how long it takes to put them together because we build all of the models first with our own hands.”

Like his father, Martin is closely involved in the day-to-day running of the company. “I make my way through this place once or twice a day too,” he says. “It means we can keep our eye on the quality and make improvements as quickly as possible.”

Creativity and ingenious engineering comes naturally to the duo. “I built my first tractor when I was in secondary school,” says Milan. “In communist-era Czechia, you would have to wait years to earn enough money to buy things such as a tractor but we needed them to grow food. So I decided to build one myself. It was a metre wide, two metres long and had a car engine and gearbox. It allowed me to help with farming our land.”

For both father and son, keeping aviation manufacturing based in Czechia is also a matter of national pride. “Our country has a strong tradition when it comes to aircraft manufacturing and design,” says Martin. “The airfield that we operate out of is owned by aircraft manufacturer Let, which was founded just before the Second World War. About 40km away, we have Zlin, which is famous around the world for how well its planes perform in aerobatic competitions.”

“Our mentality is all about creativity,” Milan says of his countrymen and women. “It allows us to develop new things quickly.”

Bringing industry back: Werkstadt Zürich’s model for city-centre manufacturing

At the edge of Zürich’s historic Altstetten neighbourhood, in an area adjacent to one of Europe’s busiest rail hubs, industry is in full bloom. Monocle is inside a cavernous brick building for a “Factory Friday” open-house event on the Schweizer Bundesbahn (SBB) Werkstadt Zürich campus. The reinvention of this former SBB maintenance hall, known as Halle Q, is the first step in a wider transformation of the former railway-operations area into a thriving urban factory that offers space for businesses of various kinds to operate right in the city centre, rather than being banished to the outskirts.

“Assembly and manufacturing can work in an urban setting,” says Christian Kaegi, whose company, Qwstion, uses banana-plant fibres to create its bags. When Werkstadt Zürich opened in 2024, Qwstion was one of its first tenants. On the last Friday of every month, members of the public are invited for a behind-the-scenes look at the design, manufacturing and repair facilities of 10 businesses. About a third of Werkstadt Zürich’s tenants now participate in Factory Friday, helping to show how things are made.

“Today there is a disconnect between the products that people consume, how they are made and what they are made from,” says Kaegi, who now runs the open-house initiative to make production more transparent to those outside the industries.

As well as Qwstion’s facilities, Werkstadt Zürich is home to natural cosmetics label Soeder, gin distillery Deux Frères and young chocolatier Laflor. Each of these companies was born and bred in Switzerland’s largest city. The development is a result of a federal mandate for SBB to generate returns from its substantial property portfolio and a policy strategy by local politicians to preserve zones for urban production in the centre of Zürich, rather than allowing it to be dominated solely by white-collar offices and housing, says Ben Pohl, an urban designer from Denkstatt Sàrl.

In 2016, Denkstatt Sàrl – now also a tenant at Werkstadt Zürich – and fellow Zürich-based urban designers kcap were commissioned to define and then design the project,” says Pohl. “One of the main reasons for their failure is a lack of a proper place to scale.” That’s why Werkstadt Zürich’s spaces range from modest 100 sq m rooms to 3,000 sq m units with eight-metre-high ceilings, giving tenants plenty of room to grow.

They held a series of workshops with nascent and would-be urban manufacturers who helped to inform the design. The idea was to build a learning ecosystem that would support planners, the owner and tenants as part of a thriving whole.

“It is a community for creation,” says Andreas Fehr, co-founder of apparel company Neumühle, another business that has joined the hub. Though factories disappeared from most European city centres decades ago, Werkstadt Zürich is encouraging entrepreneurs to base themselves in the heart of Zürich once again.

Oaxaca Aerospace’s Mexican-built plane has beaten the odds and is ready for takeoff

Based between the Mexican capital and Oaxaca City, the Fernández clan – best known for transportation business Traylfer – is developing and building a “Made in Mexico” aircraft in a country not well known for its plane-making prowess. The family’s Oaxaca Aerospace has built a series of prototypes for its diminutive Pegasus jet, with its distinctive “canard” formation (small wings at the front) and large ducted propeller at the back. The impressive PE-210A was followed by this year’s P-400T, unveiled at the Famex aerospace fair in Mexico City.

Rodrigo Fernández is the family business’s second-generation leader. The general manager says that Oaxaca Aerospace, which foresees military and civilian applications for its planes, is now ready for takeoff. The next step is to conduct further flight testing, with the goal of eventually converting the family factory that lies about a 20-minute drive from Oaxaca City into a production line for a full-fledged international plane developer.

How did Oaxaca Aerospace come about?

We’re a family business and my father is its president. For many years we specialised in fabricating trailers for transporting cargo. We have been making them for 40 years. My father has always loved aviation and has been up in those small, stripped-back Cessna planes that don’t have much technology. At some point, he wondered, “Why can’t we make a plane like this in Mexico?” and decided to do it. He began gathering together engineers and then we made our first drawings – that was in 2011. We had our first prototype by 2015 and began testing.

Was it difficult to develop and build an aeroplane in Mexico?

Yes, because there isn’t much of an industry here when it comes to making aircraft. Mexico has focused on the maintenance and manufacturing of parts, rather than on the design side. So it has been hard to find experts in aeronautics. We had to look overseas to universities and to retired people to help us keep the project moving forward. We do our wind-tunnel testing in Madrid, for example.

Have you identified a market for the Pegasus?

Our market is principally made up of emerging countries. We’re not about to take on advanced countries that have aircraft that are much more complex and sophisticated. Our proposal is more about military observation and safety missions, pilot training and things like these. There are a lot of countries in Latin America, as well as in Asia and elsewhere, that require this type of aircraft for these types of missions. If we can build a plane that has a low cost for maintenance and operation, it will be very attractive.

How far are you planning to go?

The dream is to eventually sell our planes across the globe and for the company to grow. We would also like to sell executive planes, such as a seven-seater.

aeronavespegasus.com

Steps to success

1. Believe in what you do: Passion can take you a long way. In this case, a family’s love of aviation trumped the lack of an established industry.

2. Find the right people: Don’t be afraid to look abroad. Gather experts around you wherever they are in the world.

3. Know your market: Oaxaca Aerospace knows that its offering can’t compete with advanced jets so it is creating its own niche.

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

- Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

- Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

- Eight ideas for Mexican businesses that are ripe for the taking

- Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

- The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene

Innovative entrepreneurs Ari S Heckman and Charles Brun bring fresh visions to hospitality and eyewear markets

1.

Ari S Heckman

Ash

While most US hospitality brands would be looking for big-city locations, Ash is taking a different path, opening in North American cities overlooked by larger companies. The four properties (a fifth opens this summer in Richmond, Virginia) are the work of Ari S Heckman. Part architect and part interior designer, he is also a property developer, furniture buyer and hotelier. He runs a creative studio in New York – a city where, pointedly, he doesn’t run a hotel.

Heckman seeks out what he calls “underdog” cities with overlooked building stock. In 2014, Ash’s first hotel, The Dean, opened in a former brothel in Providence, Rhode Island’s state capital. (It was renamed The Neptune in May 2025.) The Siren in Detroit resides in a 13-storey Italianate Renaissance-style skyscraper, which Ash restored to its 1920s period glory (when the city, perhaps not quite uniquely, was known as “the Paris of the Midwest”). Hotel Ulysses embraces Baltimore’s Gilded Age stateliness with a touch of camp, says Heckman, in homage to hometown filmmaker John Waters.

Ash’s shops sell vintage ashtrays, pyjamas and umbrellas, as well as a selection of custom furniture and bath products. Meanwhile, Ash Staging outfits homes for sale or rent in the hotter New York and Los Angeles property markets. Monocle sat down with Heckman to find out more.

What drew you to the hotel business?

Vibrant cities always have at least one great hotel. They become a living room or embassy for their city – they’re more than just a place for lodging. People used to go to hotels just to send a telegram. I lamented that I grew up in the era of postwar suburbanisation. I was mystified that we had vibrant, walkable urban environments all over the country – not just in New York – and hollowed them out. I found that scandalous and depressing. But I came of age during the first wave of urban revitalisation, which has been an animating force for my career. The prospect of participating in the comeback of the American city by being a hotelier excited me.

Your hotels have a cinematic quality. Was that intentional?

I want a guest to walk through the front doors and feel an all-encompassing attention to detail. Our scent is filtering through the air; the playlist matches the time of day. Every detail of the interior, from the furniture to the wall finishes, feels super keyed into the building that you’re standing in. The lighting is just so. Those attributes create this sense of fantasy and escapism, which is our value proposition. Obviously, it’s a priority that everyone gets a good night’s sleep but it should feel as though you’re going on a vacation within a vacation or on a trip within your business trip. You’re on set and living in this immersive world. I want to build multifaceted snow globes that someone can inhabit when they visit us.

Any favourite designers or furniture makers for your interiors?

Everything is custom or vintage. I love acquiring found objects and antiques, so we’re constantly shopping around the world. At our properties you can’t just identify where something came from off the shelf, other than maybe the plumbing fixtures – and we sometimes custom-design even those. For a hotel, that’s a maniacal approach. It’s why the projects take so long. Often something is particular to a hotel and it will never be made again.

Why underdog cities?

Global cities have become like expensive luxury goods. Creators and coolness have been pushed out. Underdog cities have become the places where culture is being made and nightlife is happening. Opening a hotel in Baltimore or Detroit – I like the idea of changing people’s perception and creating a sense of discovery. Then we become a partial catalyst for other new openings around us. I’m so attracted to cities because they have this unique kinetic energy: activity becomes contagious, like a flywheel effect. That’s harder in a suburb.

So no Ash country retreat?

Never say never. We are urban-focused but I am interested in other types and styles of hospitality. I would love to do an old motel project. We’re also looking at international growth and expansion to Europe and Latin America. Europe has some fascinating markets and gateway cities such as Genoa and Naples. Even Rome. We model our approach on European hospitality. We’re definitely looking beyond just underdog cities. I like underdog buildings and neighbourhoods too – places where you’re reimagining or doing something unexpected. The definition is becoming more elastic as we mature but the ethos is the same.

ash.world

2.

Charles Brun

Izipizi

“It’s a friendship story,” says Charles Brun, who co-founded French eyewear brand Izipizi in 2010 with former schoolmates Xavier Aguera and Quentin Couturier. “It’s also a family story.” The trio, who grew up together in Lyon, drew inspiration from their stylish mothers, who lamented the lack of off-the-peg but well-designed spectacles available at petrol stations and pharmacies. “Our idea at the time was to design and create cool reading glasses,” says Brun.

Now, 15 years later, the brand is setting its sights on further expansion into the US market. “We love working out of here,” says Brun as he whizzes Monocle through Izipizi’s New York office. It’s not quite as big and impressive as Izipizi House – the company’s HQ in Paris, which has a sunny courtyard – but it’s a nice space for the US arm, which has a team of eight employees. Brun used to travel frequently between France and the US but since appointing Jonathan Crespo – formerly global senior director at Oliver Peoples – as Izipizi’s North America CEO in 2024, he now visits just once a month.

Izipizi has a warehouse outside Chicago and the sunnies and specs are now stocked in more than 600 shops in the US, with more partnerships on the way (including with Goop). The brand is also testing the waters with Amazon, which will stock a core collection for a six-month trial. It’s more mass-market than usual for Izipizi, which has mostly leaned towards niche, independent stockists so far – but Brun believes that if you want to bring a European brand into the US market, you have to adapt. “We realised that everybody buys things on Amazon, including our customers,” he says.

This is all part of the plan to improve Izipizi’s footprint. “We believe that the US should be our biggest market,” says Brun. Approximately 75 per cent of the brand’s sales are concentrated in Europe but America is the brand’s largest market outside the continent. The team is meeting brokers and agents in New York to scout out locations for potential retail spaces. (Los Angeles and Miami are expected to follow.)

When the friends first launched the brand, they favoured selective distribution. “We wanted to be in the best shops around the world,” says Brun. The first major retail breakthrough came when Colette, the iconic Parisian concept shop founded by Colette Roussaux, agreed to stock their wares. “Colette understood the need for stylish options,” he says. The resulting exposure helped them to stake out space in the market. “During fashion week, tastemakers and buyers from across the globe would visit to see what products were featured,” says Brun.

Izipizi expanded into other Parisian retailers including Merci and Le Bon Marché. It secured spots in London in department stores such as Harrods and Selfridges, as well as in Asia, which now represents about 10 per cent of the brand’s global turnover. South Korea and Japan are major markets. When it launched a collaboration with New York-based Engineered Garments in Tokyo, the line sold out in three days. But Izipizi turned down many proposals from larger chains. “We didn’t want to damage the brand,” says Brun. “We were in the mindset of building it step by step and making sure that we had the best shops.”

What sets the company apart is that it offers sophistication while keeping products affordable, with an average pair costing about €50 or €60. The brand has also remained relevant by offering new riffs on classic designs, as well as dropping fresh products and collections. One big bet is a range developed with a Swiss researcher for those who struggle to fall asleep. The glasses block blue light, aiding the brain’s natural melatonin levels and helping people to doze off. Izipizi tested them on 300 insomniacs over the course of three months. “Eighty per cent of them told us that they loved it,” says Brun.

Another focus for the brand is sustainability. It has cut the carbon emissions of producing its glasses nearly in half since 2019, becoming B-Corp certified in 2023. By the end of 2025, the company is aiming for all of its eyewear to be made from bio-based materials. For the past 12 years, it has worked with a family-owned supplier in Taiwan. “We chose it because of its values,” says Brun, who sees this as one of the brand’s best decisions – not least because of the tariffs that the US has imposed on countries including China. “Our philosophy is not to overreact,” says Brun. “Step back, observe and take time before making a decision.”

Expansion is crucial for Izipizi but so is staying true to its principles. Despite being available in 90 countries and more than 7,500 shops, the brand is trying to preserve the close-knit, family-like atmosphere that fuelled its launch 15 years ago. “It has been a wonderful adventure and we want it to continue,” says Brun. He believes that a successful company is built on a strong team. “Without partners, I would be nothing. Izipizi wouldn’t be ‘easy peasy’.”

izipizi.com

Flow Hive is the beekeeping startup that simplified honey harvesting and scaled globally

Third-generation beekeeper Cedar Anderson was frustrated by the labour-intensive process of extracting honey from his hives. So, in 2015, he and his father set about developing a device that could make apiculture easier and accessible to more people. Ten years on, the Andersons are reinventing the industry with Flow Hive, a mechanism that allows honey to be withdrawn with ease.

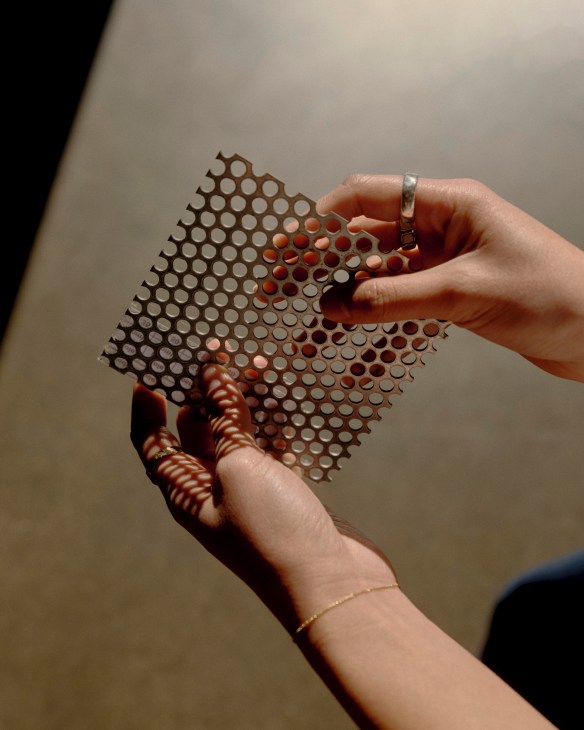

At the heart of the product is a series of rectangular plastic frames, which bees fill with wax and store honey inside, just as they would a honeycomb. To collect its contents, the beekeeper inserts a “flow key” into the top of the hive and turns it, causing the honeycomb cells inside to break. Golden honey then flows through sealed channels inside the frame and out through tubes into collection jars. Unlike conventional apiaries, which require complex equipment to extract honey from hives, the Andersons’ solution requires minimal fuss.

While the contraption was originally aimed at the commercial honey-making industry (it is capable of holding as much as 20kg), the Andersons soon realised that the streamlined process that Flow Hive offers would appeal to urban beekeepers too.

From humble beginnings in a tin shed, Flow Hive has built a global business with thoughtful design and environmental awareness. More than 100,000 Flow Hives have been installed in 130 countries, turning rooftops, balconies and suburban gardens into havens for pollinators. What began as a father-son side project now employs more than 50 staff, with its headquarters still nestled among the gum trees of their farm. Its manufacturing process has scaled efficiently, combining traditional joinery with streamlined digital production of honeycomb frames, allowing the business to meet surging demand.

The firm has also expanded its range to include pollinator-friendly gardening products, embedding itself within the climate-conscious home-and-garden movement. In redefining how we harvest honey, it has also reframed what it means to be a modern manufacturer: local, thoughtful and purpose-driven. Business is busier than ever.

How a pregnancy craving led to Dubai chocolate and a new chapter for Emirati food culture

When Dubai-based entrepreneur Sarah Hamouda was grappling with pregnancy cravings in 2021, she never imagined that she would also give birth to one of the most remarkable Emirati food-and-drink success stories in history. Dubai chocolate consists of a brick-like bar roughly the same thickness as a deck of cards, loaded with pistachio cream, tahini paste and crunchy knafeh (shredded filo pastry). The original was made by Hamouda’s Fix Dessert Chocolatier. At a relatively hefty AED68 (€16), not everyone could afford it, so cheaper alternatives to the unpatented indulgence began to proliferate, creating an entire Dubai-chocolate ecosystem.

Since then, makers from London-based chocolatiers Maison Samadi to Swiss heavyweight Lindt and German supermarket chain Lidl have come up with versions of Hamouda’s best-selling creation. Chocoart uae has launched knafeh pistachio chocolate and Chocovana Chocolaterie has taken batch orders for their pistachio-stuffed bars. Noon Minutes – Dubai’s express delivery service – has collaborated with luxury brand Vocca to make its own. Dubai Duty Free says that it sold $22m (€19m) worth of various brands of Dubai chocolate in the first quarter of 2025, equivalent to 1.2 million bars. The sweet that began as an experiment in Hamouda’s home hadn’t just gone viral – it had become ubiquitous.

What do you do when a product takes on a life of its own? Hamouda’s business partner and husband, Yezen Alani, admits feeling frustrated by copycat bars. Hamouda is more sanguine. “It’s incredibly flattering,” she tells Monocle. “It’s a testament to how influential Dubai’s appetite for creativity and innovation has become. It doesn’t annoy me. In fact, it makes me proud to have played a part in defining what Dubai chocolate means.”

Imitation bars often have little of the gooey indulgence of Fix’s original creation, mainly because these cheaper, mass-produced versions are designed to have a longer shelf life. Yet all of this activity has proved to be an inspiration for Fix.

“We’re exploring collaborations, expanding our flavours and looking into new ways in which people can experience us,” says Hamouda, hinting at plans for international expansion. She hasn’t forgotten where those first bars came from. “I think that people genuinely felt the creativity, care and authenticity behind it,” she says. “It wasn’t just another chocolate bar. Fix has become about much more than just chocolate.”

The artisans battling to keep craft alive with achingly beautiful creations

The upholsterer

Wigrens Döttrar

Stockholm, Sweden

Based in Stockholm’s Södermalm district, upholstery atelier Wigrens Döttrar is a beloved part of the city’s urban fabric. “The community around here is close-knit,” says owner Sara Lidenmark. “Locals pop by to have a chat every day and many of my clients live in the area.” That friendly, inviting rapport is central to the workshop’s reputation. “Sometimes I’m even invited to dinner at clients’ homes.”

Opened in 1926 by upholsterer Anton Wigren, the studio is now managed by Lidenmark. She joined in 2012 after completing an apprenticeship with the then-owner, making her the fifth artisan to head the studio. “For as long as I can remember, I’ve had an interest in beautiful fabric and furniture with a history,” says Lidenmark. “It’s magical to see a piece transform from something tired into a beautiful object.”

A look at Lidenmark’s order book shows locals putting in requests for the upholsterer to spruce up their armchairs and sofas. But she is also working with larger clients such as restaurants and museums. With such a variety of projects, Lindemark runs a tight ship. “Upholstering is a very creative process,” she says. “It gets quite messy when I’m working on something but I’ll have a moment after I’ve finished to stop and clean it all up. Then I’m ready to move on to the next piece.”

On the day when Monocle visits, Lidenmark is about to put the finishing touches on cushions destined for an outdoor-seating area on a roof terrace. It’s a slightly unusual job for her – but she has just as much fun with it as she does with any other project. “I love working here and having such close ties to the neighbours,” she says. “It feels so special to carry on the history of my forbearers in this spot.” Lidenmark says that she isn’t alone in that sentiment. “People know the history of this place – they want it to live on.”

wigrensdottrar.se

The weaver

Antico Setificio Fiorentino

Florence, Italy

A few minutes’ walk from the waters of the Arno, Antico Setificio Fiorentino is one of the last vestiges of Florence’s golden age of craftsmanship. The city’s old-world San Frediano neighbourhood would have once bustled with artisans. Now though, the workshops are far fewer in number and weaving ateliers like this 18th-century remnant have almost disappeared from Italy.

The team at Antico Setificio Fiorentino is determined to keep their practice thriving. “This isn’t a museum or a foundation – it’s an actual business,” says Fabrizio Meucci, a third-generation technician who handcrafts replacement parts for the heirloom equipment. “The task of keeping the company alive motivates us to work harder.”

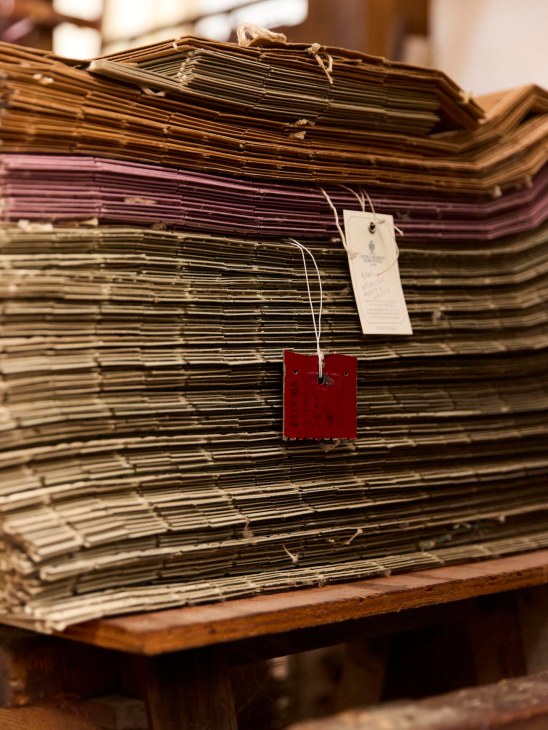

Every working day, the team weaves threads to turn out silk fabrics, from intricate fleur-de-lis jacquard to glossy satin. The more modern 19th-century looms produce 10 metres a day. The oldest wooden-framed contraption dates back to 1650 and turns out just a metre or two of fabric a day.

The space echoes with the percussive sound of the looms. Clients arrive to leaf through the fabric archive that includes Medieval and Renaissance-era designs. Some are looking to make purchases for hotels and churches. Others are drawing up plans for custom patterns or commissioning reproductions of historical materials.

The sense of how important the atelier is to the city is signified by high-end Florentine menswear brand Stefano Ricci’s decision to acquire it from locally based fashion house Pucci in 2010. “[The process was about] safeguarding the artisan techniques needed to make these fabrics,” says team member Maria Rita Agliolo Gallitto. For Pucci, it was important that the buyer was also a Florentine.

Despite the changes, the weavers have remained at the looms. And local homes and institutions will continue to shimmer with the intricacy and splendour of Florence’s ancient weaving craft for a long while yet.

anticosetificiofiorentino.com

The carpenter

Mogami Kogei

Tokyo, Japan

As the only son of a craftsman in edo sashimono (traditional Tokyo-style joinery), Yutaka Mogami always planned to join the family business. Playing in his father’s workshop from early childhood, he entered the craftsmen’s ranks at the age of 23. “In this part of Tokyo’s historical Kuramae district, there used to be workshops making sashimono furniture, platformed geta sandals, woodblock ukiyoe prints and more,” says the 71-year-old Mogami. “But now many of them have been replaced by apartment buildings.”

Despite this, makers remain central to the community in Tokyo’s old downtown area. Mogami’s workshop has been in business for more than a century – and the ability to change with the times has been key to its longevity. While Mogami’s father passed on his craft by training 12 apprentices, co-founding the Edo Sashimono Co-operative Association and paving the way for the craft’s official national recognition, Mogami has sought to merge traditional joinery techniques with modern designs. Keeping the studio open and accessible to visitors is key to its success.

“Many people arrive with an idea based on something that they’ve seen in an exhibition or in a relative’s home,” says Mogami. Sets of drawers are made to order from wood native to Japan, such as zelkova or paulownia, while family Buddhist altars and paper andon lanterns finished with urushi lacquer are also popular choices. “I’ve even been asked to make a gunbai, the wooden baton used by the referee in sumo wrestling bouts.”

Mogami isn’t shy about letting customers see him at work. Seated on the floor with his chisels, hand-planes and saws, he crafts dovetail joints and beveled edges entirely by feel. It’s a process that reinforces the value of sashimono – these meticulous details are often concealed within the finished product. “A true craftsman finishes each and every detail, even those parts unseen.”

sasimono.ciao.jp

Why selling a brand is about getting back to basics

“Terence Conran would say, ‘It’s better for customers if everything is designed with a single pair of eyes and a singular vision,’” says Mark Landini. After starting his career in London and working for the likes of Fitch & Co – and then as creative director of the Conran Design Group – the Sydney-based designer founded Landini Associates with his wife and managing director, Rikki, in 1993. Today they have 24 employees, four children and Chester, a Staffordshire terrier-sheepdog mix, who is the most vocal presence at the firm’s office in Surry Hills.

Over the course of more than 30 years, the studio has become renowned for developing cohesive brands across retail, hospitality, beauty and more. Despite its current standing, however, it had less polished beginnings. The initial idea for the practice came about after a night of drinking.

Landini, who had long worked for Conran, had been offered a partnership in an architectural design outfit in Sydney but realised within a few weeks that it wasn’t for him. “We bought a couple of bottles of cheap champagne from a shop called Liquorland,” he says. “About two bottles in, I wrote a letter to the managing director of Liquorland and said, ‘Your bottle shops are rubbish. You’ll never have any credibility in wine. You need to start a wine shop.’”

Landini never imagined that he would receive a response but the phone rang within days and a relationship began. This eventually led to him designing the company’s new fleet of wine shops known as Vintage Cellars, then reinvigorating the Liquorland brand. “We had our first clients,” says Landini.

The practice has since become renowned for reviving and reinventing brands, with a broad church of clients. Supermarket firms Aldi and Esselunga, fashion labels Glassons and Petit Pli, Australian tea retailer T2, cosmetics brand Jurlique and even McDonald’s are now on Landini Associates’ books. And while the clients and the end products are substantially different, there is a consistent approach across the firm’s creative process.

“We have this thing called the blindfold test,” says Landini. “The idea is that if you were kidnapped, blindfolded and then taken to a brand’s space, you should be able to recognise exactly where you are as soon as the blindfold comes off.”

The designer explains that to create such a space, his team – regardless of who the client might be – works to build physical spaces that are neutral in form, allowing the product to become the most important element. “If you can find a way of creating an environment that celebrates the product and the brand is immediately recognisable, then you have passed the blindfold test.”

However, the blindfold test is only worthwhile if the brand in question has a clear core idea. “The word ‘brief’ means short and precise. That’s why when you write a brief for a company, it should be brief,” says Landini.

Three projects of note

“We don’t have a fixed list of client services,” says Landini. As a result, a job might encompass everything from identity evolution and graphic design to interiors, lighting, signage, packaging and uniforms, as well as the digital experience. What does unite the firm’s projects, however, is the approach taken: identifying a single driving idea, often distilled to a few words. Here we outline three Landini Associates projects to show how the company works across scale, industries and business requirements.

1.

Esselunga

Supermarket, Italy

Driving idea: ‘Dimmi’

(Italian for ‘tell me’)

“We had worked in Canada for 15 years with Loblaws supermarket, starting with Maple Leaf Gardens, and it introduced us to the Caprottis in Italy,” says Landini. The Caprotti family owns supermarket chain Esselunga, which began in the country’s north and now comprises 192 shops. It also has the highest turnover per square metre of any supermarket globally.

“It started with the notion of dimmi, which means ‘tell me’ in Italian,” says Landini, explaining that the driving idea for the project was to show the work that goes into Esselunga’s products. “We did this by putting the bakers, pasticceri, salumerie and chefs in a glass box at the front of the shop to expose customers to the wonders of what they do.”

2.

Jurlique

Cosmetics, Australia

Driving idea: Biodynamic Beauty

Landini Associates was commissioned by Australian biodynamic skincare company Jurlique to reinvigorate the brand. “We started by visiting its flower farm in South Australia,” says Landini. “It was obvious to me that if it wanted to make the brand big, it had to celebrate the smallness of it – to tell the story of the biodynamic farm.” The Landini team went on to create a logo, packaging and shop fit-outs inspired by the shed on the farm.

3.

McDonald’s

Fast food, USA

Driving idea: Make McDonald’s cool again

Landini Associates developed “Project Ray”, which has been rolled out over the past 10 years. The first shop to be overhauled as part of the initiative was the Admiralty Station outpost in Hong Kong. One of the busiest McDonald’s locations in the world, it serves an astonishing 1,200 customers per hour.

“The brief was basically to make McDonald’s cool for millennials,” says Landini, who made a point of developing uniforms that would be equally at home in a nightclub and on the production line. “We also changed the furniture and turned the lights down.”

How to build real estate businesses from conversion, not demolition

When property entrepreneur Ben Gattie set out to restore one of his first heritage site in Singapore, he began with a disused 1920s-era biscuit factory with high ceilings and an ornate stuccoed façade. The site had been unoccupied for a couple of years and, though it was a little weathered by time and neglect, Gattie immediately saw its potential. Within a year, it had become The Working Capitol, a co-working space, complete with a lively mix of cafés and restaurants.

“Thanks to the building’s conservation status, it couldn’t be torn down,” says Gattie. “Instead, we considered how we could bring it to life. And it turned out that the site’s character made it the ideal property for the project. It helped us to attract and anchor the dream tenants that we wanted alongside the corporate ones.”

The Working Capitol was just the first of many. Today, Gattie’s Singapore-based real-estate company, Triple P, oversees more than 35 conservation properties across the island state’s Chinatown neighbourhood. Indeed, restoring heritage sites has become its principal mission.

“Adaptive reuse gives you flexibility,” says Gattie. “We can develop our layout and user experience based on a property’s unique configuration. It is exciting when you can instil your brand vision around a property, instead of the other way around.”

Part of the appeal of working with heritage sites for property projects is that, in addition to their uniquely Singaporean identity, these spaces tend to be distinctive enough to attract both international and local brands. Triple P’s constellation of heritage buildings along Keong Saik Road, for example, has enticed several global tenants, including Indonesian hospitality brand Potato Head and Canadian athletic-clothing retailer Lululemon, which sit alongside home-grown brands such as milliner Hat of Cain and restaurant La Cabane. And just around the corner at 89 Neil Road, a factory that once produced herbal pain-relief medicine Tiger Balm now accommodates bespoke workspaces for businesses that include software company Figma and concert promoter Live Nation.

For the next phase of Triple P’s growth, Gattie is focusing on residential projects. The firm has acquired two old walk-up style apartments in the Little India district, on the doorstep of the city’s business quarter. These have been repurposed into 16 individual residential units for a co-living operator, which opened earlier this year and offers easy access to the city, as well as a sense of community and security.

As an entrepreneur, Gattie saw an opportunity in a city that is renowned for its make-it-new attitude but also has a wealth of underutilised architectural marvels. “When working with heritage sites, you have to remain open-minded,” he says. “There has to be a compromise between nostalgia, romanticism and practicality for the spaces to be both special and commercially viable.”