The Entrepreneurs

The best places in Austria balancing entrepreneurial ambition with a high quality of life

SET UP HERE 01

Bregenzerwald, Vorarlberg

Aiming high

Where the Western and Eastern Alps meet, you’ll find the bucolic Bregenzerwald region – where age-old craft traditions are keeping design and hospitality thriving.

Schwarzenberg’s Hotel Hirschen is run by siblings Peter and Pia Fetz, its 10th-generation family owners. Last summer, seven years after taking over from their parents, they opened a new bathhouse and pool that complements the main building, a shingle-coated 18th-century inn. “I don’t need facilities with seven saunas and 12 pools but I want a bit of a spa,” says Peter with a smile. “I had never found a small hotel with the right features and saw a niche for us.” He beams as he shows us around the three-level bathhouse, designed in white fir by Austrian firm Nona Architektinnen.

Some in the village of Schwarzenberg saw the project as a radical proposition. It took Peter more than five years to secure the building permit, which had to be green-lit by 21 neighbours and 14 government agencies. “One neighbour asked me how I intended to prevent her cat from drowning in the pool,” says Peter, who now sees the funny side. The discussions involved lots of beer, wine and schnapps. “There was no sober solution to that problem,” he says.

But once everyone was on board, the project progressed smoothly. The companies of 37 regional craftsmen worked on the building, which was completed in just eight months, exactly on schedule.

This is the gentle pace at which business often proceeds in Bregenzerwald, which lies a 30-minute drive from Bodensee. Here, the rolling hills are kept trimmed, whether by lawnmower or grazing cow, and most buildings sport a well-kept layer of wood shingles. The population of 32,000 has a mentality of “schaffe, schaffe, Häusle baue” (“work, work, build a house”), which supports a thriving construction industry. Little by little, Bregenzerwälders are developing a new crop of small but sturdy businesses that are improving the quality of life for residents and visitors alike.

After a morning massage and swim at Hirschen, guests might head for lunch at VauLand, a quarter of an hour away in Hittisau. There, they are welcomed by Christian Vallaster, who cooks dishes using pasta that he makes by hand in the back room. The gregarious chef produces a dozen varieties, all from Austrian durum wheat.

Vallaster is originally from neighbouring Feldkirch. He admits that an artisanal business would be easier to run in a bigger city. So why did he choose Bregenzerwald? “For my wife – and for the views!” he says. But he adds that the region’s culinary scene is developing fast. “We’re famous worldwide for our craftsmanship and now our gastronomy is building a reputation. We’re not known for pasta yet but we will be.” Sampling VauLand’s freshly made ravioli with cheese and herbs, monocle finds it easy to agree.

Another business helping to lift Bregenzerwald’s culinary reputation is Gut Gereift, which operates two cheese cellars in Egg and Andelsbuch. Founded in 2020 by Hilda and Melchior Simma, it buys wheels of Alp and Bergkäse from nearby producers, matures them for as long as three years and sells them online using a self-built platform that facilitates group orders. These “order communities” extend from Vienna to Helsinki. “We have teachers, offices and pensioners,” says Hilda. “There is a social element too, of bringing people together.”

The idea came to Melchior when he was a procurator of a regional bank and worked on a voluntary basis for a small co-operative dairy. He reckoned that it wouldn’t be a struggle to sell the region’s excellent cheese, which is made exclusively from hay milk and is handmade. “We have an unbeatable product,” says Hilda. “Our philosophy is to work with what’s already there and build on it.”

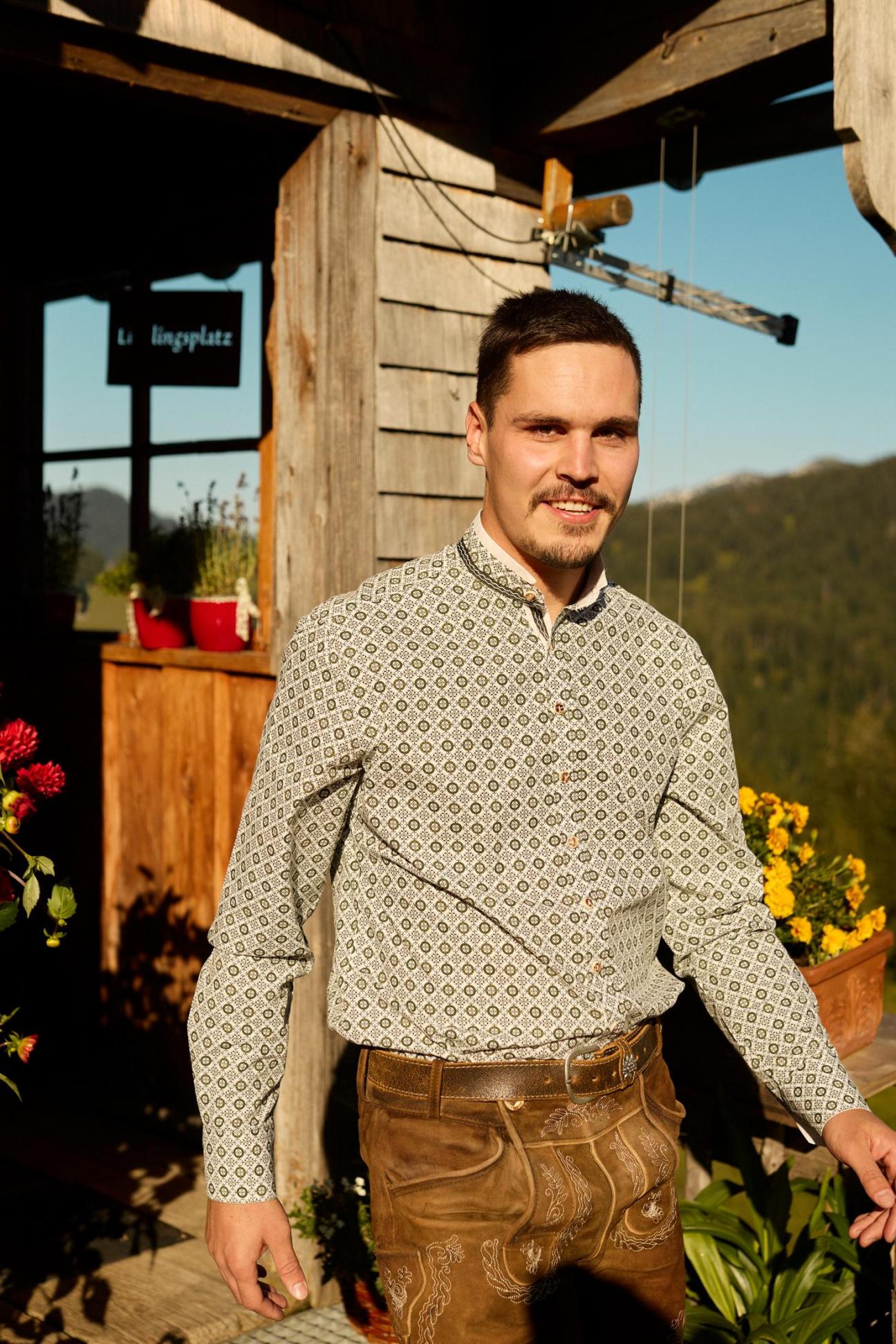

Trek up to Burgl-Hütte, a traditional mountain hut close to the German border, and you’ll find a similar approach. It was run by the same family for 60 years until 1994 and was well known for rollicking evenings when only wine and Skiwasser were served. In 2022, the now 25-year-old Thomas Mennel took it over after returning to his home region – as many are doing – following a bartending stint in Barcelona. He started managing the hut with his parents, Edith and Edwin.

Many of Bregenzerwald’s new businesses were founded by returnees. Pius Kaufmann, a native of the region, and Flora Ohrenstein relocated here from Vienna in 2020. Ohrenstein had spent a summer working at an organic farm nearby. “I swam in the river every day after work,” she says with glee. “I started asking Pius whether he wanted to move there.”

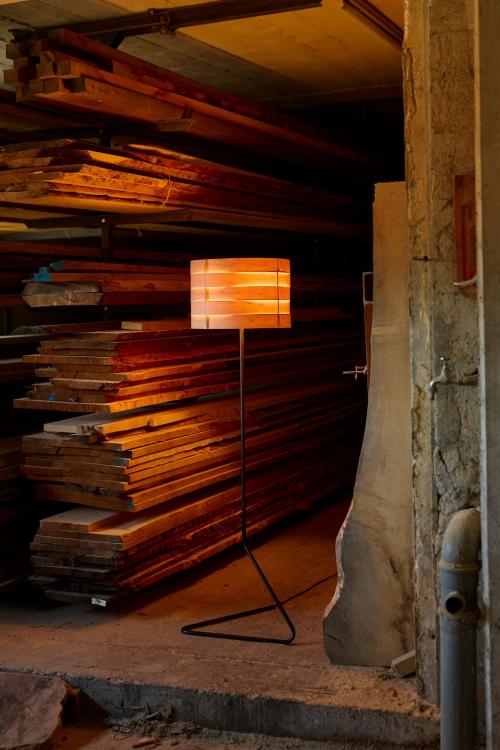

The couple rented a workshop in Egg and founded their business Lampen und Möbel (lum). Pius, who trained as a carpenter, builds bespoke commissions in solid wood for clients and has developed a line of lampshades made with bentwood veneer. The firm presented for the first time this year at Handwerk 1 Form, a trade fair organised by Werkraum Bregenzerwald.

Bregenzerwald’s new crop of entrepreneurs might not be building major industrial operations but the smaller businesses help to make the region’s tradition of impeccable craftsmanship more available to the wider world. Jürgen and Evi Haller of Tempel 74 apartment hotel, are examples of this evolution. With his eponymous architecture firm, Jürgen has built dozens of multimillion-euro homes in the area. In 2018 the couple bought a plot of land just across the street from their house in Mellau. In co-operation with their neighbours, they filled it with two interconnected buildings that host Jürgen’s office and the holiday apartment. Construction started in February 2019; the Hallers welcomed their first guests nine months later.

Tempel 74 has a double duty as a showcase for Jürgen’s practice while enabling visitors from afar to experience living in a Bregenzerwälder-built apartment. “Here, everyone’s dream or life mission has always been to build a house for themselves,” says Evi, who personally welcomes all of the hotel’s guests. “We are wilful people who want to do things properly. But the same mentality and passion is also what makes for a good host.” —

SET UP HERE 02

Graz, Styria

Driving ambition

Austria’s second city has a well-earned reputation for creativity – and is now an entrepreneurial outpost of the culture sector.

Unlike Salzburg or Vienna, Graz isn’t weighed down by the ghosts of historical figures such as Mozart or Freud. It’s an outlier among Austrian cities, a gateway between the Slavic and Italian worlds to the southeast and Austria’s heartland to the north. Perhaps this crossroads aspect is why Graz has long been a hub of creativity, not just in culture but in industry too.

The city is home to several important cultural events. Every autumn, it hosts the Steirischer Herbst arts festival; in March and April, it welcomes the Diagonale, an annual showcase of Austrian cinema. These festivals draw visitors and help to keep the hotel and restaurant scenes lively.

In terms of hospitality, Graz is again a little different from other Austrian cities. When the Radisson opened in summer 2024, it became one of only a tiny handful of international chain hotels here. The city has long been dominated by smaller hotels such as Kai36, managed by Verena Lam. “Though it’s the second-biggest city in Austria, Graz still feels a bit like a village,” she says.

Automotive and mobility firms, including avl and Magna, have traditionally driven business in Graz and its surrounding area. Weitzer Woodsolutions, based in the nearby city of Weiz, is dedicated to reintroducing wood to the mobility industry; it is now collaborating with Magna and Volkswagen in a design-development partnership.

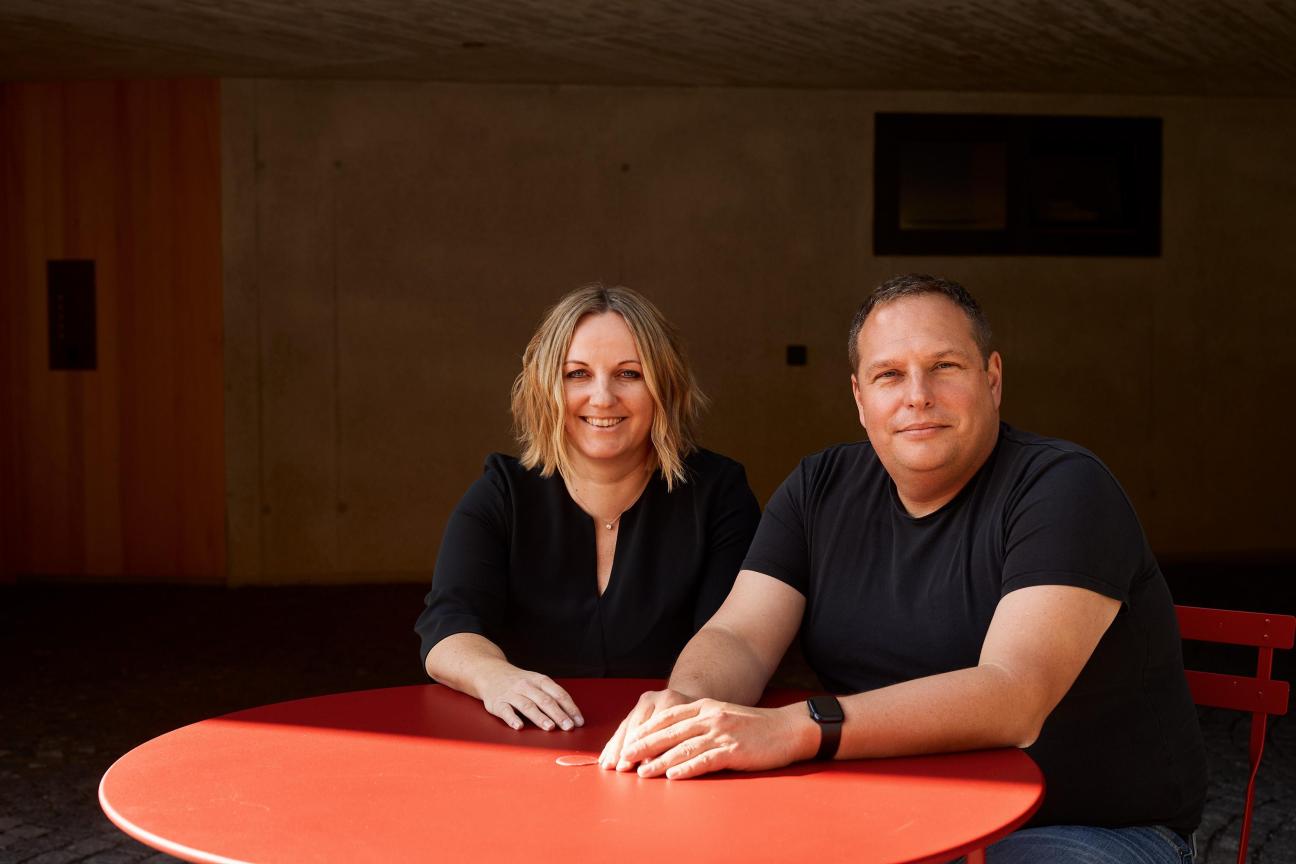

Such collaborations are flourishing in the region. Networking organisation Creative Industries Styria (cis) has nurtured the region’s entrepreneurial spirit since 2007. It is led by Eberhard Schrempf, whose name is known to nearly every business owner here.

For Schrempf, a new era began when Graz was named a European Capital of Culture in 2003. Not only did this lead to large-scale construction projects but it prompted some reflection. “There was a discussion about what lay next for Graz and it became clear that we needed something to bind together our unique mix of art, design and industry,” he says.

One key priority for Schrempf is to spread the idea that design isn’t just for the elite. “We need to see it not as a luxury but as something that creates products for everyone and for every day.”

Despite the challenges that he faces, he’s not worried about the future of the creative industries. “Creativity is in Graz’s dna,” he says. —

SET UP HERE 03

Linz, Upper Austria

Reaching out

Long a hub for trade and industry, this forward-thinking city is now raising its ambitions in technology.

For decades, Linz held a well-defined place on Austria’s economic map. Sitting on the Danube and connected to trade routes across Central Europe, it was a hub for heavy industry and woodworking. Indeed, Voestalpine, the country’s largest steel producer, and Schachermayer, a metal- and woodworking company, continue to provide jobs and contribute to the city’s infrastructure.

A new chapter began in 1979 when Linz hosted the inaugural Ars Electronica Festival, celebrating art, science and technology. A permanent Ars Electronica Center followed in 1996, with a striking glass-fronted building completed in 2009 – in time for the city’s stint as a European Capital of Culture.

Artist and curator Hideaki Ogawa first exhibited at the centre in 2006 and remembers the excitement at that time. “I didn’t plan to stay here but somehow I kept coming back,” says the Tokyo native. Attracted to the city’s focus on technology, Ogawa progressed through various research roles until, in 2019, he became a co-director of Futurelab, Ars Electronica’s r&d arm (he later became its managing and artistic director).

Unlike the centre and festival, which receive public funding from the city and state, Futurelab collaborates with businesses to drive research. In 2010, Asimo, the humanoid robot created by Japanese conglomerate Honda, was showcased at the Ars Electronica Festival as part of a project exploring human-machine interaction. “Asimo was right here,” says Ogawa, posing in the lab’s main demonstration room, which also hosts immersive installations. Another collaboration, with Germany’s Siemens and the Johannes Kepler University, resulted in the development of a body-scanning system to help medical students better understand human anatomy. “It’s crucial that our work doesn’t stay within these walls but is distributed beyond, creating new opportunities,” says Ogawa.

This technological shift has swept through Linz’s industrial zones too, transforming its sprawling former tobacco factory, the Tabakfabrik, into a major centre for business and culture. The site now houses about 250 companies and organisations, including galleries, two departments of the University of Arts Linz and even a brewery. Each of its five main buildings is named after a brand of historic Austrian cigarettes. The complex is listed, making major renovations tricky, but Tabakfabrik’s co-ceo, Denise Halak, says that the city, which owns the site, does everything possible to reduce red tape. “The city showed courage when it bought the factory from Japan Tobacco International in 2009, as there was no clear plan for its future,” she says. Step by step, the site has flourished, becoming an anchor for innovation, linking Linz’s emerging businesses with its traditional industries.

“With its rich history, Tabakfabrik and Linz as a whole are perfect hubs for creativity and innovation,” says Michaela Scharrer of Creative Region, a service hub for creatives. Scharrer and her team host breakfast meet-ups for Tabakfabrik residents and those seeking collaboration. “We have a huge network, so if someone approaches us, we know immediately who to connect them with,” she says.

Down the corridor is the Strada del Startup, a hallway lined with the offices of entrepreneurs. One of them is Florian Holzmayer, the founder of Balcosy, which creates attachable window seats designed as an alternative to balconies. “I came up with the idea during the coronavirus lockdowns when I missed being outside and the community here was instrumental in getting it off the ground,” he says, before dashing off to the breakfast room for a kipferl.

Part of this support network is mkrz Lab, which uses craft to enhance internal communication and critical thinking within companies, including product prototyping. Co-founder Tobias Zucali believes that these skills should be developed at an early age. “In school, you’re mostly focused on transferring knowledge from books into a child’s mind,” he says. “We need these hands-on methods to teach abstract thinking.” —

SET UP HERE 04

Salzburg

Hitting new peaks

Best known for its natural beauty, Austria’s fourth-largest city is worth its salt when it comes to supporting start-ups too.

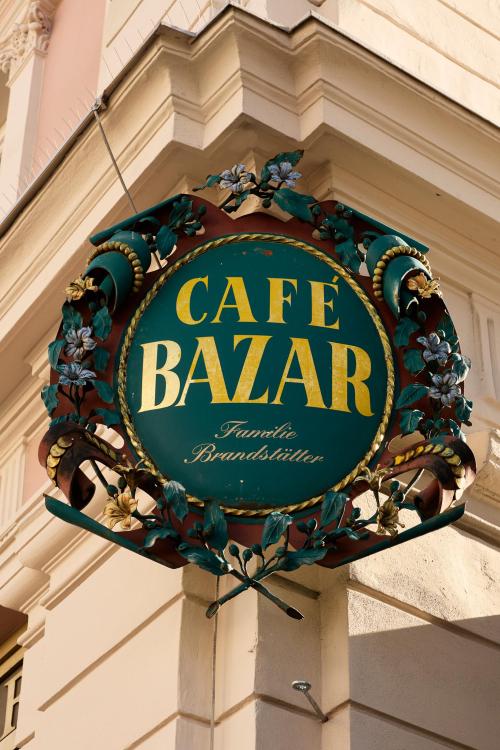

“Things come together in Salzburg,” says Evelyn Brandstätter, director of Café Bazar, from the terrace of her hostelry in Austria’s fourth-largest city. There’s a buzz among the patrons at the family business, where she has worked for 20 years. The striking scenery – with the Salzach river glistening beneath the Mönchsberg mountain – and slow pace of life are key aspects of the city’s allure.

Among those who have moved to Salzburg in search of a better work-life balance is Spanish architect Roberto R Paraja, who set up the main office of Haro Architects here with co-founder Bernd Haslauer. The pair, who work on a mix of residential projects and restorations of public buildings, are impressed by Salzburg’s strong network of craftspeople. “There are various kinds of carpenters – the Tischler for furniture and the Schreiner for construction,” says Paraja. “In Spain we don’t have Zimmerers, with their level of specialisation in wooden construction.”

Katharina Macheiner and her family run roastery and coffee shop 220Grad. One of its three sites is next to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, from where the city looks like an attractive place to while away an afternoon. “I’m from here but didn’t know that all of these cool people were here,” says Macheiner.

Her sense of optimism is echoed by Startup Salzburg, a regional business incubator co-ordinated by Innovation Salzburg. Its outpost in the Techno-Z Technology Park is abuzz with would-be founders. Though tourism and retail are the city’s biggest sectors, information and communication technology is the industry to watch, with 600 companies from across the globe now based here.

“Our network is strong in terms of the number of companies and players,” says Natasa Deutinger, the head of Startup Salzburg. “Being a one- stop shop is one of the city’s biggest strengths.” The incubator is promoting smaller companies in the technology sector, such as Sproof, which develops digital signature software, and cyber-security company Solbytech.

“Our network tries to make the best environment for innovative founders,” says Lorenz Maschke of Salzburg Economic Chamber. But he admits that competitive advantage alone probably isn’t the clincher for those considering a move to Salzburg. “You have to be prepared to pack your skis and walking boots and have some fun,” he says. —

made in austria

From designers crafting lighting, cutlery and furniture to the canny engineers behind folding bikes and skis, we round up some of our favourite Austrian firms and products that you might otherwise miss.

SKI BOOTS AND SKIS

Hannes Strolz and Kneissl

Not long after skiing arrived in Austria, Ambroz Strolz set up a shoe workshop in Lech. His leather boots became all the rage after being displayed at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris and remain at the forefront of the sector today. Another leader when it comes to Alpine essentials is Kneissl, which has made high-quality skis in Kufstein for almost a century.

hannes-strolz.com; kneissl.com

TEXTILES

Zur Schwäbischen Jungfrau

Based in Vienna’s city centre, Zur Schwäbischen Jungfrau has produced fine linens since 1720. Originally a supplier to Austria’s aristocracy, the 300-year-old business was revitalised when Hanni Vanicek took over in the late 20th century and added some modern appeal. Now, alongside her nephew Theodor Vanicek, she offers products ranging from tablecloths to items for aeroplanes and yachts.

zsj.at

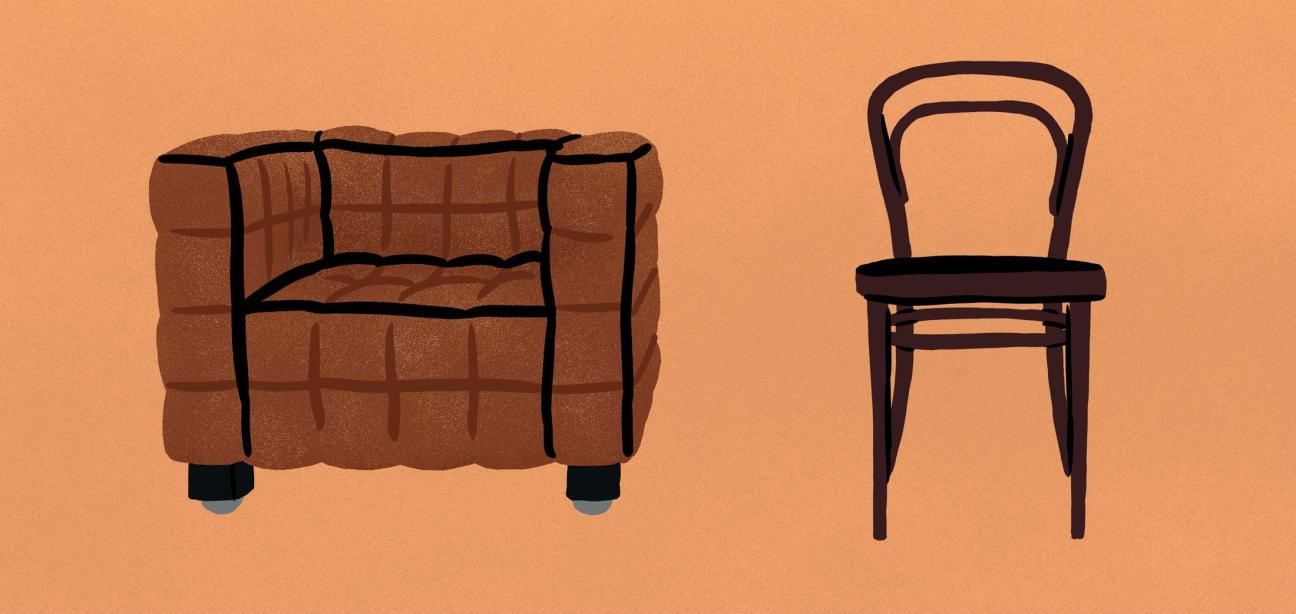

CHAIRS

Thonet and Wittmann

Michael Thonet’s bentwood chairs became instant classics when they were launched in Vienna in the mid-19th century and the chairs remain staples of Austria’s cafés. Meanwhile, family-run Austrian company Wittmann, now in its fifth generation, is best known for pieces such as Josef Hoffmann’s distinctive Kubus chair.

thonet.de; wittmann.at

WAFERS

Manner

The pink packaging bears the word “Neapolitaner” but these wafers are resolutely Viennese. Made and run between Vienna and Wolkersdorf by a company of about 700 employees, these toothsome treats are made from sustainable cocoa and sold in more than 50 countries. The timeless packaging has hardly changed since the product was first listed in the company’s catalogue in 1898.

manner.com

HATS AND SOCKS

Mühlbauer and Bolter

Austria’s eye for quality clothing is unmatched and Mühlbauer should be your go-to for handmade millinery. Its three-step steaming, blocking and trimming process plays to the strengths of its fine felt. Tyrolean hats and turbans sit beside baseball caps in the brand’s 1st district shop in Vienna. For hosiery, look no further than Bolter in Koblach for merino-wool socks to keep you warm in a cold snap.

muelbauer.at; bolter-socks.com

CARE PRODUCTS

Saint Charles Apothecary and Susanne Kaufmann

Sixth-generation pharmacist Alexander Ehrmann has been running Vienna’s Saint Charles Apothecary since 2006. The space, which dates back to 1886, stocks simply packaged products made from natural ingredients, many of which it mixes in-house. Meanwhile, Bregenzerwald cosmetics company Susanne Kaufmann shows that Austrian firms have what it takes to go global.

saint-charles.eu; susannekaufmann.com

GLASSWARE

J&L Lobmeyr, Swarovski and Riedel

j&l Lobmeyr has produced glassware since 1823 and is currently run by the family’s sixth-generation leaders, Andreas, Leonid and Johannes Rath. It originally specialised in chandeliers but Lobmeyr moved on to lighting, tableware and more, and now works with the best new designers. Glass is a clear winner in Austria – just look to Swarovski over in Wattens and Riedel in Kufstein.

lobmeyr.at; swarovski.com; riedel.com

MOTORBIKES

KTM

Originally founded as a repair shop in Mattighofen, Upper Austria, in 1934, motor-vehicle manufacturer ktm now has 21 different models in production. Its first foray into the motorbike sector in 1953 resulted in the stately r100. Today, ktm is thriving in the world of two-wheeled transport and sells more than 250,000 units across the globe per year.

ktm.com

SHOES

Ludwig Reiter and Rudolf Scheer & Söhne

Launched in 1885, shoe manufacturer Ludwig Reiter is now led by Magdalena Reiter and Anna Reiter-Smith, along with cousin Joseph Potyka-Zeiler. It’s best known for its welted soles for shoes that are now sought after across the world. Vienna’s oldest bespoke shoemaker is Rudolf Scheer & Söhne; its shop in the city is worth a visit in its own right.

ludwig-reiter.com; scheer.at

LIGHTING

Kalmar

In 1881, Julius August Kalmar founded Kalmar in Vienna. The firm, which initially specialised in handmade bronze objects, was among the first to work with architects to create lighting. Now in its fifth generation, the family business continues to produce fine lighting and bespoke pieces for clients in hospitality, commercial, marine and residential projects worldwide.

kalmarlighting.com

SKI LIFTS

Doppelmayr

Doppelmayr, founded in Wolfurt in 1893, continues to elevate the ski-lift experience for customers across the globe. It offers ropeways and chairlifts with heated seating, plus cabins that carry your kit and gondolas that climb slopes at speeds of more than six metres per second. Today it’s responsible for more than 15,000 installations across 96 countries.

doppelmayr.com

CERAMICS

Augarten

Handmade for the past 300 years, every piece of Augarten pottery is unique. The company is Austria’s finest purveyor of daintily decorated, pastorally patterned ceramics and the occasional art nouveau gem. Its reputation has never wavered. The products made at the original factory are referred to as Alt Wien (“Old Vienna”) porcelain; no trip to the capital is complete without a visit to the facility.

augarten.com

CUTLERY

Jarosinski & Vaugoin and Wiener Silber Manufactur

Led by its sixth-generation owner, Jean-Paul Vaugoin, this cutlery business offers styles ranging from classic sets to baroque decorative tableware pieces. Its wares have been forged at the same workshop in the Austrian capital’s Neubau district since 1847. Wiener Silber Manufactur has maintained a similarly august reputation for cutlery since 1882.

vaugoin.com; wienersilbermanufactur.com

STREET-FOOD BIKES

Paul & Ernst

Dreamed up by product designer Paul Kogelnig and architect Ernst Stockinger, Paul & Ernst’s customisable street-food bikes can be fully assembled in 30 seconds and have accommodated everything from people peddling oven-fresh wood-fire pizzas to cocktail carts. Ding, ding: there’s no excuse not to get into the saddle and take your business on the road now.

paulandernst.com

Editor’s letter: Andrew Tuck on adapting to change to run a thriving business

This handbook of entrepreneurship is designed to entice you to start your own venture, question the business that you already have (or find yourself employed by) and also to meet people who have managed to leap over some of the hurdles that companies inevitably encounter. We also hope that this magazine will provide you with glimpses of some of the more fun moments in an entrepreneur’s life.

Much has changed in the world of business since we first launched this annual. There was, for example, the coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent shifts in how people wanted to work (in some markets). With these changes has come a desire to find a way of working that feels more meaningful and worthwhile. The reverberations from these themes can be felt throughout the stories and interviews that appear on these pages. We look at how the office has evolved to keep staff happy and engaged, and at the macro trends that are shaping our cbds.

We then venture into urban neighbourhoods that have become start-up hubs – in cities from Kuala Lumpur to Seattle – and sit down with business leaders (and a Danish philosopher) to find out how to run a potent enterprise today.

After the 2023 edition’s focus on the uae, this year we take a deep dive into the businesses that make Austria tick. Our special nation survey looks at how the country marries a deep understanding of making and craft with a commitment to developing new technologies and trades. Our survey unpacks all that the nation has to offer investors, start-ups and people just looking for inspiration. We’ll whisk you from Vienna to Graz, Bregenz, Linz and beyond, with many Alpine stops along the way.

Over the years, this magazine and Monocle Radio’s The Entrepreneurs podcast have told the stories of numerous businesses both fledgling and established. Who knows? Perhaps your new venture will be featured here next time. If you have ideas for stories or some sage business advice to share, drop me a note at at@monocle.com. And don’t forget to listen to The Entrepreneurs, available at monocle.com and all podcast platforms. ––

10 hard-earned business lessons from car salesman Patrick Moylett

Patrick Moylett is director of Harrington’s of Fulham, a used-car dealership in west London. He has also found success selling tweed, property and condoms. Here he shares 10 of his top tips.

1.

In the beginning, sell quickly and…

When I was in property, I noticed that customers were slow to pay because negotiations took so long. If the setting-up costs are too big, you might become one of the 60 per cent of new businesses that fail. So I moved into selling cars: buy them, do them up, sell them. There’s instant reward.

2.

…buy cheap

In the mid-1980s I noticed that old Jaguars were quite cheap so I bought two to get started. I drove from London to Normandy in one and in Paris I stopped at an antiques shop. When I returned to the car there was a man waiting who wanted to know if it was for sale. Parisians loved the old Jaguars so I started driving to Paris once a month in one and parking it on the Champs-Élysées with a “For sale” sign on the windscreen. I made a lot of money.

3.

Decide whether you’re a lone wolf

As I was starting out, I thought, “I want to do this alone”. That’s just the way I am. Other people work better with partners. It helps if you realise this early on.

4.

Selling is easier if you don’t have to explain things

Take an existing product and market it for a new use. Marketing is the most expensive part of a young business. I started selling condoms during the Aids crisis, when their use was still considered largely contraceptive. I marketed them as a prophylactic but didn’t have to spend much on explaining what they were – most people already knew.

5.

Spot opportunity abroad

When I was in France at the age of 18, I realised that every apartment door had a spy hole, which they didn’t have in my native Ireland at the time. So I bought 3,000 of them and took them to Ireland in a box and went door to door in Dublin selling them.

6.

Look at horizontal ways of selling

After I started my condom business, Red Stripe, I began thinking about how the idea of protection could apply to other products. So I started selling Red Stripe-branded cycle gear and rain protection.

7.

Follow your joy

The use of condoms was still very controversial when I was getting into the business – Ireland was very conservative at the time. My girlfriend’s family was strongly against it. So I drew up a list of pros and cons. The con list was very long and the pro list had just one thing: I enjoyed it. So I decided to continue.

8.

Get out there

I was in the lobby of the Time Out offices in London when I overheard two journalists talking about a condom shortage. I told them that I had a business and asked whether they would interview me. I restarted my business the next day and was on the cover of Time Out. It was invaluable publicity.

9.

Choose the right name

When I bought my first car showroom, I called the company Harrington’s of Kensington, even though it was just a railway arch in Ladbroke Grove. I wanted people to associate the brand and the cars with an expensive area of London.

10.

Learn how to read people

As soon as someone comes into my showroom, I can tell whether they will buy a car from what they say and do. I’ve saved a lot of time by not chasing lost causes.

How three founders turned their passions into success stories

1.

Chris Tag

Founder, Defy

Before founding Defy, a maker of hardwearing bags, Chris Tag was an art director for Ogilvy. “I would work for nine months on a commercial that would disappear in two weeks,” he tells monocle. “I always wanted to make something a bit more meaningful that would last longer.”

Tag set up Defy and started taking on freelance jobs in 2008 while it got going. He challenged himself to have all of the cutting and stitching for his new brand done in Chicago. It took years to get there but Defy now ships to more than 30 countries, with a loyal following among Japan’s luggage connoisseurs. Two years ago it bought out Lee Sewing, a family-owned manufacturer based in Chicago.

Tag’s pivot from advertising began with some cast-off billboard vinyl. “I saw that you could make something from it. So I dragged it out to my Mini Cooper, put it in through the sunroof, then taught myself how to sew by watching YouTube.” He sold his first messenger bags to his co-workers. “Everyone paid cash, so I had $1,000 [€895] in my pocket.”

Defy’s materials have since had an upgrade but keeping manufacturing local has been key, allowing the brand to nimbly develop new ideas and test them out on the market. “Scaling this by going overseas isn’t appealing,” says Tag.

In switching careers, Tag set out to make something that could stand up to corporate culture. The business plan came later. “I said I’d be profitable in a year – but that became two, then three. Everyone talks about following your passion, which is quaint, but think through the economics and whether you can make a living from it.”

defybags.com

2.

Philipp Mayr and Dominic Flik

Co-founders, Kaisers Smoked BBQ

Philipp Mayr and Dominic Flik left their careers in industrial design 10 years ago to start Kaisers Smoked bbq, a barbecue stall next to the butcher’s at Graz’s main farmers’ market in Kaiser-Josef-Platz. “We just got bored with our jobs,” says Mayr, laughing.

Their design expertise stood them in good stead when they built their stall. “You can’t stop being a designer, even when you’re dealing with how food is presented on a plate or how the tables are situated,” says Flik.

When they founded Kaisers Smoked bbq in the early 2010s, there was a dearth of barbecue equipment in Europe, so the pair’s first smoker had to be imported from Tennessee. The result is quite possibly the only authentic US-style barbecue joint in Styria, the Austrian province where Graz is the capital.

Kaisers Smoked bbq opens its doors early, serving up smoky flavours until 22.30 from Monday to Saturday. The work is more demanding than in Mayr and Flik’s previous careers but they don’t mind. “Now we are never bored,” says Mayr with a smile.

kaisersbbq.at

3.

Bianca Gerber

Founder, Les Bois

From her office in Zug, Switzerland, Bianca Gerber tells monocle how her passion for interior design comes from her painter father and tailor mother. “Our house was full of incredible antique furniture,” she says. Gerber started her career as a paralegal in a Zürich law firm. But she bridled at the buttoned-up nature of the profession and the fact that she was working for a large organisation. “I couldn’t get used to the idea of being employed by someone else for the rest of my life,” she says.

She made the jump at 35, quitting her job in Zürich and moving to London for a furniture-design course at Central Saint Martins. Getting a degree allowed her to obtain the credentials that she needed to build her own company.

Back in Switzerland, she founded Les Bois, a design studio working with Swiss carpenters to create durable wooden furniture. “The brand focuses on minimalism, with a clean, honest and contemporary design that also celebrates its passion for raw material.”

Gerber’s background gave her an invaluable well of knowledge when negotiating the often-tumultuous legal road of solo entrepreneurship. “I’m by myself making big decisions and handling any issues with the producers,” she says. Les Bois now aims to open a showroom in the near future. “It’s worth the risk when you’re building something yourself. It’s the best decision that I ever made.”

shoplesbois.ch

The 20 best pieces of advice from business leaders

For many top ceos and brand founders, running a successful business is about more than just profit and loss. Here, savvy entrepreneurs interviewed on Monocle Radio provide us with top tips on everything from starting a meaningful venture and working as a team to achieving the perfect balance between productivity and play. For more advice from clever companies and people with bright ideas, tune in to Monocle Radio’s weekly business-oriented shows, The Entrepreneurs and Eureka. —

1.

Be nimble and don’t chase perfection.

“You’ll never make a perfect product. In a start-up, you have to move quickly. But that’s your unfair advantage: the ability to capture the market and show customers how exciting this journey is.”

Andrei Danescu, co-founder and CEO, Dexory, a London-based robotics company.

2.

Challenge convention.

“Given the perfume industry’s roots in France and Italy, I often get asked why I’m creating a fragrance in Spain. My answer is simple: 27 87 is about modernity and that’s what Spain represents. The country can become a new reference for innovation in perfumery.”

Romy Kowalewski, founder, 27 87, a Spanish perfume brand.

3.

Lunch is for brand builders.

“St John’s mantra is: ‘Always the same but never the same.’ We don’t know what we’ll do next or where we’ll be but our methodology always involves lunch. It’s part of the collaborative process to help our partners understand each other’s values and have fun working together on the project.”

Trevor Gulliver, co-founder and CEO, St John restaurant, a UK hospitality business.

4.

Understand public service.

“Working in public service gives you a deep sense of responsibility towards other people. It taught me the importance of helping communities to overcome challenges and of ensuring their safety. That commitment translates into the private sector, where the focus remains on serving individuals, whether through environmental programmes or consumer products. Success stems from understanding and addressing the needs of people.”

Lisa Jackson, vice-president of environment, policy and social initiatives, Apple.

5.

Set the right example.

“Be ready to change course to uphold your values. Our mission is to protect the ocean, so when we learnt that a popular fabric in our wetsuits had a higher impact on the environment than other materials, we didn’t hesitate to halt production and switch to more sustainable alternatives, despite pushback and higher costs.”

Madeleine Wallien, founder,Wallien, a Dutch women’s waterwear label.

6.

Engage in a creative outlet.

“As medical doctors, we spend a lot of time in the hospital, so we ensure that we have a creative escape. Our lives are filled with all sorts of colours and shapes, which inspires new projects.”

Paul Jaklin, co-founder with Amanda Bianca, Dazurelle, a Swiss design label.

7.

Craft a better future.

“We must set competitive prices and design quality furniture. People won’t buy from us just because we’re from Ukraine. We have to find new customers to purchase our existing models, all while developing new products that can compete in the global market.”

Julia Lisovska, commercial director, Tivoli, a family-run furniture manufacturer in Ukraine.

8.

Find your voice.

“Speakers bring their personal baggage onstage; they’re too worried about themselves. This is the biggest mistake that you can make after not having an end to your speech. It’s not about you – it’s about your audience. By focusing on them and trying to understand what they need to hear, the nerves will eventually disappear.”

Marcus John Henry Brown, founder of Speakery, a German business that trains speakers.

9.

Don’t rely on legacy alone.

“The market is competitive and to succeed in new areas you have to approach it as if you were a start-up. Heritage provides a solid foundation but to stand out you need to balance that with fresh thinking, finding ways to innovate and creating a sense of aspiration.”

Neel Bradham, CEO, Parador, a German flooring company.

10.

Play to your strengths.

“I often describe our business as the ‘smallest developer in Hong Kong’. We try to avoid direct competition with the big players by being selective about the sites that we pick.”

Keith Kerr, founder and chairman, The Development Studio, a property developer in Hong Kong.

11.

Take inspiration from the best.

“Longchamp’s Le Pliage has long dominated the global bag market but is it still cutting edge? We questioned to what extent it was sustainable and functional when designing our own bag and have since crafted the ultimate versatile tote. It’s lightweight, spacious and stylish – a Mary Poppins bag for your life. This sense of flexibility is at the heart of Vee Collective.”

Lili Radu, co-founder, Vee Collective, a sustainable brand of lightweight, versatile totes tailored to modern consumers’ needs.

12.

Leverage tradition.

“Greece has a rich history of working with silk. When we started the company, however, the nearby silk town of Soufli was all but abandoned. Thankfully, a revival took place with the advent of affordable digital silk printing and people started working with silk again.”

Vassiliki Zafiria Ypsilanti, founder, Mantility, an online silk-scarf retailer blending Greek tradition with modern fashion.

13.

Evolve your brand.

“We have been around for five years now, so we didn’t want to stagnate in terms of our designs. Our autumn collection is a reflection of this evolution. But we also have a permanent collection that our customers love and can come back to.”

Phyllis Chan, co-founder, YanYan, a Hong Kong-based knitwear label.

14.

Foster an emotional connection.

“We aim to spark joy with all of our products. If you use something every day, such as a hairbrush, it should bring you happiness. That’s why we craft luxury functional objects.”

Flore des Robert, co-founder, La Bonne Brosse, a luxury hair-care brand.

15.

Refine your ideas.

“What I love most about business is polishing rough diamonds – taking an idea, assembling the right team and fine-tuning every detail. It’s the thrill of making something shine. Once the diamond is polished and ready for the world, I’m happy to hand it over. That’s when I start thinking about the next big thing.”

Dumi Oburota, founder of Severan – a wine company – and co-founder of record label Disturbing London.

16.

Mix fun and function.

“Maintaining a personal creative practice is crucial for me. Two years ago, my company shifted to a four-day working week, keeping Fridays open to focus on creative interests. Whether it’s ceramics, photography or connecting with new people, this approach has been a game changer. It keeps the energy fresh and the balance works well for all of my employees.”

Leslie David, founder, Leslie David Studio, a creative practice based in France.

17.

Keep solutions simple.

“Our line is genderless and trend-free, focusing on timeless collections every season. This innovative approach challenges retailers, as a one-size-fits-all range can be tough to sell online. The products’ styling is oversized and you can create different silhouettes with the larger shapes. Take our elasticated trousers, for example, which are an easy product to wear. There’s no fuss. Once buyers experience the high-quality South Korean fabrics that we use to make our clothes, the effortless wear and standout style are obvious.”

Kanga, founder, Kappy Design, a South Korean fashion label.

18.

Be open to new opportunities.

“I’m a dreamer but I push hard to achieve my goals. For me, design is universal. If you can design a house, you can design a yacht, art or jewellery. I’m ambitious but once I’ve achieved something, I’m quick to move on. Been there, done that. What’s next?”

Miminat Shodeinde, founder, Miminat Designs, a London-based interior architecture and design studio.

19.

Focus on development.

“Our skincare line took more than three years to perfect in an award-winning lab in Osaka. Japan leads the way in product innovation, constantly rethinking and reinventing formulas. That cutting-edge approach was our driving force. We kept our range minimal to start with. Every detail had to be right.”

Nora Kato, co-founder, Ipsum Alii, a Zürich-based Japan-made skincare brand.

20.

Have pride of place.

“Our mission is to prove that an Africa-based brand can grow into a globally recognised luxury powerhouse by harnessing local resources and manufacturing.”

Laduma Ngxokolo, founder, Maxhosa Africa, a South African high-fashion label.

What makes a great leader? Five business minds share their vision

1.

Gen Fukushima

CEO, Sanu

It’s a balmy afternoon as Gen Fukushima inspects the greenery dotted around the new headquarters of Sanu, a Tokyo-based company that provides second homes through subscription and co-ownership models. The 37-year-old ceo points out the species endemic to various regions and altitudes, brought together to add a forest-like feel to the ground-floor café, taco stand and event space. The company’s offices upstairs are fitted out with bespoke furniture made from Japanese larch. By bringing together natural elements from far and wide to the Nakameguro neighbourhood, the company wanted to create a place unlike any other. “That’s why we called it Nowhere,” says Fukushima with a smile.

The idea of living with nature has been central to Sanu since its inception. Seeking a new challenge after roles with McKinsey & Company and the Rugby World Cup in Japan, Fukushima founded the company in late 2019 with fellow entrepreneur and outdoor enthusiast Takahiro Homma. Striving to create a nature-focused business without causing harm to the environment, the duo developed a subscription-based service providing exclusive access to their network of villas within several hours’ drive of Japan’s key urban centres. Despite the founders’ purpose-driven ethos, financing proved a challenge at first. “We were confronted by the fact that sustainable and regenerative approaches didn’t translate into funding,” he says. “The reality was that, for Sanu’s approach to be acceptable, it needed to have economic benefits and profitability.”

To overcome this, Fukushima and his team sought to demonstrate that there was a viable market. Harnessing the power of social media, they gathered a small group of members for the initial launch of five villas in two locations. “We think of our first members as a community of people working with us to change society,” says Fukushima. This approach paved the way for financial backing from the likes of property company Mitsui Fudosan and venture-capital firms Goldwin Play Earth Fund and Mizuho Capital. The members established connections through frequent visits, providing insights and introductions that aided the company’s growth.

Launched during the pandemic, amid rising discussions around remote work, mobility and the urban-rural divide, Sanu’s second-home service has gained momentum, demonstrating the value of catering to the needs of nature-seeking urbanites. The company has attracted ¥12bn (€77m) in funding and thousands-strong waiting lists. Plans are under way for 200 villas across 30 sites by the end of 2025, with a view to international expansion in the future.

In the face of this interest, Sanu has remained committed to being a role model for regenerative business, planting trees on its sites and sourcing timber locally. “There was the idea that it would be more efficient to generate wealth, then circulate it back into sustainable initiatives,” says Fukushima. “But during that process, a company can lose sight of its motives. To have a positive effect, principles need to be built into the roots of the business. From the outset, we operated Sanu based on the pillars of business, creativity and sustainability.”

In a year when Sanu has achieved B Corp certification and a new co-ownership project sell-out, Fukushima is excited by the prospect of forging deeper connections through the newly opened headquarters. “Integrity is essential to what we do,” he says. “I could have said being an entrepreneur is about dreams, curiosity or persistence. But in the end, it’s about someone who changes lives, brings people together and has an impact on society.”

sa-nu.com

2010

Joins McKinsey & Company, working on strategic planning, government projects and green energy.

2015

Founding member of Sunwolves rugby team. Works on 2019 Rugby World Cup.

2017

Joins Backpackers’ Japan as a non-executive director.

2019

Sets up Sanu with Takahiro Homma.

2.

Zanele Kumalo

Curator, Design Week South Africa

Zanele Kumalo, who started her career as a magazine editor, is now one of South Africa’s savviest tastemakers and entrepreneurs. After shifting her focus away from the media industry, she launched a content studio and joined Kalashnikovv Gallery in Johannesburg as associate director. Now she has added a new role to her CV: curator for the newly launched Design Week South Africa, which ran in Cape Town and Johannesburg in October. Here, she shares some tips on how creatives can get ahead in the country’s design scene.

Why did you decide to get involved in Design Week South Africa?

When I worked in magazines, I tried to amplify voices that weren’t usually given much space. What drives me now is helping young creatives find a firmer footing in places where they haven’t had access. There’s a wealth of talent in this country. Highlighting creatives makes me happy.

What advice would you give someone seeking a break in the design scene?

Start with commitment and dedication to your skill and story. To “put yourself in the room”, make sure that your product or service is the best quality. This will spur word of mouth. Make it easy to be discovered. Spend time immersing yourself in the industry: go to expos, talks and workshops, check out showrooms, ask questions and read publications that are connected to different industries. Understand how you can connect with diverse brands. The more people get to know you, the more they’ll give you opportunities or offer you information that will help you understand the market.

How easy is it to set up a design business in South Africa?

There aren’t many legal obstacles if you want to set up something quickly. Starting a new business is encouraged and there has always been an entrepreneurial spirit here, especially at the moment because youth unemployment is quite high. We were so closed during apartheid, blocked from importing a lot of things, that we built a healthy manufacturing system. When the country opened up, things changed and factories closed but there has since been a rebirth and reinvigoration when it comes to pride in local produce.

How important is branding?

If you don’t get it right at the start, it can be very detrimental. It’s not just about aesthetics; it’s about who you are and what you represent. It’s your first opportunity to impress people and you can always make tweaks down the line.

What are the biggest challenges facing South Africa’s design scene?Sustainability is difficult for many emerging businesses, as is maintaining quality. Getting your hands on the best materials can be so expensive. Production can also be hard to scale up. My advice is to collaborate: find a peer or mentor who you respect and admire, and who might have been in the game for a little longer than you have.

How will Design Week South Africa affect the local scene?

What’s interesting about it is that, while other expos usually ask those who want to exhibit to pay for a booth, there’s no barrier to entry here. People can also enjoy design in a way that feels more accessible. Instead of taking place in a single space, it’s spread across cities, so it presents a different kind of opportunity for the ordinary person on the street – you might walk into a restaurant and find a pop-up or panel discussion going on. The event is also an opportunity to amplify designers and give them a greater platform to share their brand internationally and create more sales.

designweeksouthafrica.co

2007

Becomes beauty editor and bureau chief at Elle SA.

2016

Opens dim sum bar Town with four co-owners.

2017-2019

Serves as a judge for the 100% Design SA award.

2023

Joins Kalashnikovv Gallery as associate director.

3.

Vorravit Siripark

CEO and founder, Pañpuri

Across Pañpuri’s range of hand creams, face cleansers and perfume oils, Andaman Sails is its bestselling scent. A blend of bergamot, green tea and moringa oil, it’s named after the sun-drenched sea that laps the southwestern coast of Thailand, the brand’s home market.

Vorravit Siripark founded the Bangkok-based fragrance and skincare company in 2003 and more than two decades later – buoyed by the aroma of Andaman Sails, along with some savvy decision making – it is winning market share from both international beauty giants and the domestic competition. “I can comfortably say that we have become the number one brand in our segment,” says Siripark, who is all smiles following a recent business trip to Japan.

At the end of this year, Siripark expects to announce a new partner that will help him to take the company to what he calls the “next level”. Annual revenues are forecast to exceed thb1bn (€27m) for the first time and the company is expanding across Asia, which is the largest beauty market in the world.

The brand’s first Hong Kong shop opened in August. It will open an outpost in Singapore next year and in mainland China in 2026 – proof that international shoppers are willing to pay a premium for Thai products. “The tide has turned,” says Siripark, who talks to monocle at Pañpuri’s flagship wellness spa in the Thai capital, close to where he opened his first tiny shop with personal savings and seed capital from his brother and sister.

The 47-year-old never really set out to be an entrepreneur. He chose management consultancy – a career that took him around the world, including a stint in New York – because it sounded more fun than investment banking. Returning home after obtaining a master’s degree in luxury goods management in Milan, he spotted a gap in the market: Thailand was known for wellness but the best hotel spas in Bangkok only used foreign products. “We don’t really have that many luxury brands coming from Thailand,” he says. “I want to build a legacy for Thailand that lasts and doesn’t just rely on me alone.”

This purpose and passion – two of his three guiding principles – have driven him ever since (his third “P” is people). Siripark credits the company’s current success to the decision that he made in 2018 to bring in a Thai private-equity firm. Lakeshore Capital’s investment enabled Pañpuri to recruit the best senior management from international brands and transform an owner-operated family business into a more professional company. “You need a good team to help you excel – to expand and to grow,” he says.

This injection of fresh capital, industry knowledge and best practice laid the foundations for a series of tough calls during the coronavirus pandemic that are now paying dividends. Chief among them was investing in physical retail, which accounts for the vast majority of sales. Money was spent on larger spaces with unique designs that could deliver the full brand experience.

“We focused on the quality of every shop and realised that we don’t have to be everywhere,” says Siripark, who plans to mirror this success overseas by moving away from department-store concessions run by third parties. “We have learnt along the way that to control quality, especially for a luxury brand, the distributor model might not be the right approach.”

Lakeshore will soon exit its investment but Siripark is in it for the long run. He and his siblings still control the majority of shares in the company and purpose still drives him in everything that he does. “Building a luxury brand is like running a marathon,” he says. “You need perseverance and patience – and when you think that the finish line is near, the race just keeps on going.” Pañpuri certainly has the wind behind it as its signature scent sets sail for the rest of Asia.

panpuri.com

2003

Pañpuri founded in Bangkok with Siamese Water Milk Bath and Body Oil.

2004

First retail concession in Bangkok.

2011

Pañpuri candle wins Japan’s Good Design Award.

2017

Launch of most popular scent, Andaman Sails.

2024

Hong Kong retail debut with scent Heaven Moon Osmanthus.

4.

Morten Albaek

Philosopher and author

According to Danish philosopher Morten Albaek, the pursuit of a work-life balance is unwise. The founder of business consulting firm Voluntãs, which has more than 100 staff worldwide, instead believes that we should be seeking meaning and a sense of belonging in all that we do – and that requires taking life as a whole. monocle met Albaek at Unleashed, a Nordic summit organised by Stockholm’s handelskammare (chamber of commerce), and quizzed him about the region’s potential, why he believes that corporate success is easy and how to do work that matters.

People often think of Nordic nations in terms of how happy they are – which they seem to be, according to the data. But you believe that there’s a better way of looking at how people’s lives, including their experiences of work, are unfolding in this region and beyond. Could you tell us about it?

First, we need to decide what we want to achieve. Do we want cities and societies that are happy because they are satisfying most of their citizens’ needs? Or do we want to create meaningful societies and cities? If it’s the former, the Nordics are doing well – on a misguided metric. But if it’s the latter, the countries in the region have quite a journey to undertake. Look at the Nordics from a meaningfulness perspective and dive deeper into their labour markets, and you’ll see that we aren’t among the frontrunners. We’re among the average-to-poor performers.

So what’s happening?

It’s important to understand the definitions of satisfaction, happiness and meaning. People feel a sense of meaning when they stand in the now, reflect upon the life that they live and, regardless of whether what they see is positive, negative or neutral, look forward to what lies ahead. If you research labour markets in the Nordics – and globally too – you’ll see the conditions that have to be in place for a person to find meaning in their life and the work that they do. They need to experience four things at the same time: purpose, personal growth, a sense of leadership and belonging.

In terms of those four drivers, the Nordics are below the global average. Indians, Mexicans and Kenyans find going to work more meaningful than Swedes, Norwegians or Danes do. That might sound pretty absurd but it’s what the data is showing us. So, of course, people have been searching for explanations. Is it because workers in the Nordic region are lacking purpose? No, not at all. We derive a significant amount of purpose from our jobs. But what we are missing here is a sense of belonging.

My hypothesis is that we are seeing the same challenge across Nordic civilisation that we’re seeing in the labour market: we are losing our sense of belonging. The interesting thing is that everybody agrees that if you don’t belong somewhere, you are lost. You need to belong to a family and a community, and you also need to feel that you belong at your workplace. But if you were to ask how many Nordic corporations or municipalities measure this sense of belonging, you’ll learn that the answer is none. To create cities and societies in this region that are existentially superior, we must understand that we are currently facing the deterioration of meaning among those who live here.

What is stopping people from finding this sense of belonging?

If you don’t believe that the life awaiting you will be a more dignified one than what you have today – that the future is more hopeful than the present – you won’t find any meaning in your life. And in the Nordics, we are probably less hopeful than we once were, though the data set to show this didn’t exist 20 years ago because my colleagues and I were the first to create it. Adults aged between 25 and 34 are struggling to find meaning in life and at work. That brings me to another thing that’s very important, probably the most astonishing thing that we have discovered in our research. Globally, an average of 49 per cent of the total meaning of life for working people comes from the jobs that they do. In Sweden, that figure is 37 per cent but, in the Nordics overall, 39 per cent of people’s ability to derive meaning in their life comes from the fact that they find their work meaningful. That fundamentally kills off the idea of a “work-life balance”.

On this topic, you have argued that you’ve got one life and that you need all of its aspects to be aligned – your work and your everyday life should be considered in the same breath.

Yes, if 49 per cent of the meaning of your life, on average, comes from whether your work is meaningful, how can you ever talk about dividing your life and work?

Should you only do work that is meaningful or is it the role of businesses or governments to think about how they can add a sense of significance to people’s lives?

Government is the last resort in this part of the world. To go back to the Nordic average, if approximately 40 per cent of the meaning of people’s lives comes from work, corporations and organisations that employ them have a responsibility to ensure that they organise and design their leadership and work processes in a way that doesn’t lessen meaning – but instead provides it. Again, what’s essential to meaning is a sense of belonging, personal growth, leadership and purpose. We have been doing our survey in different organisations for almost a decade and our global study for five consecutive years, so the data pool is getting bigger and bigger. And what is the most important contributor to meaning at work? You might assume that it’s leadership but that’s the least important factor because it can never instil meaning in the employee’s life.

A leader is a facilitator, meaning that his or her responsibility is to provide space for a sense of belonging, purpose and personal growth. Leadership is not about being a divine figure who enters the room and suddenly everything is meaningful. Instead, it’s a matter of whether you foster an environment in which people can feel that they belong and can be who they are. You don’t have to dress up and you don’t have to dress down. You don’t need to change your language or abide by norms that don’t ring true to you. And you don’t have to say things that you don’t believe. You find the purpose in what you do and you see it contribute both to your life and to a greater good. So the leader is not even a servant – just a facilitator.

You are a philosopher but you have also worked in big organisations. Was that important in developing these ideas about the world and work?

Since Kafka, there haven’t been many intellectuals, let alone philosophers, who have been so deeply involved in multinational, commercial, capitalistic organisations as I have. I spent 15 years as a philosopher, studying the capitalistic commercial system from the inside. I climbed the career ladder so aggressively because it was so simplistically primitive, so one-dimensional.

We have to understand that, ultimately, business has no complexity. It’s just about the need to control cost by ensuring that sales are higher – that’s it. You might tell me that you also need a great idea. Yes, most companies were founded by somebody who had a great idea and is no longer around. A lot of managers are just custodians of a business created, say, 100 years ago and they just do the two things that I said. That’s why it’s fairly easy to get a seat at the high table. The only thing that you need to say is, “I will now show you how you can reduce your costs and increase your earnings. Do you want to listen?”

But if I were to say, “I’ll tell you how I’m going to increase your employees’ quality of life,” the bosses would be afraid that I was suggesting that they should all do some yoga. When we enter the room, it’s with an acceptance of the capitalistic system. We just want to transform it into a humanistic version of that.

But you don’t question clients’ desire to make a healthy profit?

I want to prove – and, in fact, have proven – that you can earn more money, more quickly, by providing your employees with a higher quality of life and increasing their sense of meaning.

Finally, what are the things that you need to do as a company to start thinking about meaningfulness?

You have to understand and accept the differences between meaning, satisfaction and happiness. If you don’t do that, you will be wasting your own time – and certainly mine. Second, you must make clear what your company is and what you want it to be. How can people know whether it would be meaningful for them to work there if you have not been crystal clear about who you are and who you want to become? Then you need to make your vision of your culture scalable, bring that manifesto into your business processes and gather data. You should measure what you treasure and your organisation’s sense of meaning. Alternatively, you could just continue doing what you’re doing: you might get rich but you’ll just be repeating the capitalistic models of the past and not improving the life quality of those who work for you.

Morten Albaek is the author of several books, including ‘One Life’. His latest, ‘Falske Sandheder i Livet’ (The False Truths We Live By), topped the bestseller lists in Denmark and will soon be published internationally.

5.

Chiara de Iulis Pepe

Head of wines, Emidio Pepe

An early pioneer of low-intervention methods, 92-year-old Emidio Pepe is among the most respected names in natural wine. This year his vineyard in Italy’s Abruzzo region is celebrating its 60th anniversary. Its head of wines is Emidio’s 31-year-old granddaughter, Chiara de Iulis Pepe, who studied business at the Sorbonne and winemaking in Bourgogne. While she is carrying on her grandfather’s traditions – grapes picked by hand and pressed by feet, and wine refined by long ageing processes – she is also applying an entrepreneurial mindset and pioneering new techniques to address climate-change-related challenges. By raising Emidio Pepe’s profile, she has elevated the reputation of natural wine among connoisseurs. Meanwhile, her sustainable practices are inspiring even large-scale producers as changing environmental conditions impact vineyards of every size.

How do you change natural wine’s image to move it beyond its status as a niche product?

There are many misconceptions about natural wine – that it has defects, that it can’t be elegant, that it can’t be aged because it doesn’t have a lot of added sulphites. That’s why I don’t use the term “natural wine”. I prefer simply to explain our ethics and how we work: with biodynamic farming, manual handling of grapes, strictly indigenous yeasts and long ageing processes.

How did you rethink Emidio Pepe’s approach to sales?

We stopped doing the big wine fairs. Convention centres are not the right venue for talking about high-level wines produced with such care and craft. Now we bring buyers to us in Abruzzo. We show them the vineyards and how we take care of our land and our wines. Our communication strategy is very time-consuming but it provides a truer portrait of our product.

As an artisan producer of wines, how do you grow the business?

We can’t boost production so we’re increasing the ageing of our wines, which gives them more value. I’m building a new cellar to allow us to age more bottles. It’s an economic model that’s very different from the wider wine world’s approach of simply maximising quantities.

What challenges do you face as the third generation helming the winery?

When my grandfather was starting out, his neighbours thought that his ideas about ageing Montepulciano wines – and of manual and chemical-free agriculture – were crazy. He was very forward-thinking. I need to be the same way when it comes to dealing with global warming. Making top-level wines in a changing climate is a challenge. My generation faces weather conditions that aren’t predictable or cyclical. If I want to continue making wines for the next 30 years, I need to take important steps in the next three or four years.

How did you shake things up when you came on board in 2020?

The biggest things involved dealing with climate change: planting vines in new locations, adding water reservoirs and shade. I also devised an agroforestry technique in which grapevine rows are lined by trees and protected by their shade. It’s called the Pepe Pergola.

Some major wineries are starting to incorporate natural practices. What can they learn from you?

They need to recognise that monoculture must end, with a return to biodiversity on farms, and that spraying the soil with chemicals only brings us closer to the desertification of our farmlands. They have to stop growing only what they can sell and start thinking about being custodians for their piece of earth.

emidiopepe.com

1964

The Emidio Pepe winery is founded, using chemical-free and manual farming from the start.

2005

The winery converts to biodynamic farming.

2020

Chiara De Iulis Pepe, age 27, takes over the winemaking and vineyards.

2022

She introduces the tree-shaded Pepe Pergola method of vine-growing.

How HQs with in-built factories are keeping staff engaged and improving their products

Big clothing, furniture and design firms today tend to make their products in locations far from where they are conceived. Perhaps it was globalisation and rampant offshoring that drove this? Or maybe it had something to do with the coronavirus pandemic, which helped workers to make the case that they could fulfil their roles from anywhere? Whatever the cause, how things are created can often feel detached from a company’s day-to-day operations.

Luckily, many entrepreneurs are now seeking to bridge the gap between conception and final product by integrating manufacturing into their office spaces. Why? It offers employees opportunities to test ideas more responsively and bring better products to market at greater speed. This can help employers to cultivate a more engaged workforce, as staff are able to see the fruits of their labour almost immediately.

Here, we visit design firms that chose to bring production in-house. From the pair who followed a thread that took them from the US to Morocco and the firm seeking a competitive advantage in Japan to an Italian firm that found a fresh use for some former stables, each reimagined their workplace to help them gallop ahead with their plans. —

1.

Beni Rugs

Tameslouht, Morocco

It’s fair to call Beni Rugs’ founders, Robert Wright and Tiberio Lobo-Navia, a tenacious pair. Back in 2015, Wright was in Morocco for a photoshoot involving the shoe brand he worked for at the time. He ended up buying several handmade rugs from a shop in Marrakech and shipping them back to New York. The rugs were an immediate hit with friends but both Wright and Lobo-Navia, who had joined him for the end of the trip, had noticed that the buying process wasn’t the smoothest. “Basically, it was hard to find a design you loved in the size you wanted,” says Lobo-Navia, who everyone calls Tibs. The couple saw a gap in the market for a beautiful product sold online that was easier to buy and came in living-room-friendly sizes. They set about turning Beni Rugs into a reality.

Despite not having any experience in the rug industry and few contacts in Morocco – a country with its own set of social, cultural, religious and linguistic complexities – Wright found himself on a plane bound for Marrakech the following spring. “I found my way back to the same shop,” he says. “I approached the owner and told him we had this custom-rug idea and wanted to work with him. He said, ‘Absolutely not. This is a crazy idea! You have to understand that Moroccan weaving doesn’t work like that.’”

That sort of initial knock-back would have been enough to sink an idea for many budding entrepreneurs. But not Wright and Lobo-Navia who, drawing on their wells of tenacity, weren’t put off at all. Wright says they had a “gut feeling” about the idea and it was enough to try a different tack. They approached the owner’s cousin and tasked him with convincing his family member to hear the pair out. The plan worked and Beni Rugs officially launched with six looms and 12 weavers.

Things have come a long way since the website first went live in 2018. Its founders organised the first photoshoot at a friend’s modernist home in Michigan that same year. Wright and Lobo-Navia may no longer be married but they call each other “family” and clearly share a common vision. Indeed, their shared desire to push boundaries also led to the signing of the lease for the new headquarters in 2020, rented from artist Mohamed Mourabiti. Located about half an hour’s drive outside Marrakech in the town of Tameslouht, the HQ embodies just how far the brand has travelled. Painted in a bright blood orange that contrasts with the deep blue of the cloudless Moroccan sky, stepping through the gate feels like entering a sanctuary – or perhaps a high-end rescue centre given the number of cats milling about, all of them given “Spanish old-lady names”, jokes Lobo-Navia, such as Hortensia and Jacinto.

Walking past a garden full of olive trees, succulents and cacti, as well as a pétanque court, you arrive at an impeccable showroom which feels influenced by Lobo-Navia’s years working in New York’s hospitality scene. There’s a red 1970s Togo sofa from Ligne Roset in front of a wood-and-marble bar with a La Marzocco coffee machine perched atop it. There are Clara Porset chairs from Luteca and a stunning locally made table in square pieces of Thuya wood; on its surface a collection of weaving books and antique trinkets. Next door’s office has a pair of mid-century sputnik chandeliers in Murano glass from a vintage dealer in Marrakech, while the walls are covered in Moroccan cork. Everywhere you look there are soft, colour-popping rugs underfoot, arranged with such taste that you want to step around rather than over them.

One of the things you notice about the rugs is that the designs are contemporary and don’t immediately nod to Moroccan aesthetics. “Part of the aim was to not appropriate traditional designs,” says Wright, who adds that the idea has always been to use Moroccan weaving talent and techniques – from flat woven to knotted – to create something different. The founders knew from early on that, for several factors including quality control and consistency, they needed to bring weaving in-house and “vertically integrate” as Lobo-Navia calls it. “We learned along the way,” he adds. “Every system we’ve built from the ground up, on our own.”

Although slowed by the pandemic, the Tameslouht atelier, showroom and headquarters opened in May 2021 after extensive refurbishment driven by the founders’ desire to create the right working environment. “This building was dark and broken up, with the courtyard walled in,” says Wright. Windows were installed around the central external space, where a 150-year-old olive tree was planted and a fountain added. “Our whole idea was to have transparency between the business side and the weaving.”

Hortencia the cat surveys the Beni Rugs showroom while shaded by Clara Porset chairs from Luteca

Beni Rugs’ HQ started with about 20 weavers, all of them women, and the number has since grown to 65. A new atelier opened in Sidi Zouine at the end of September, employing 20, and with the capacity to grow to more than double that number. Wright and Lobo-Navia are also eyeing another production facility, all part of creating centres of weaving talent. And while the brand still works with the initial partner for some orders to to a growth that more than tripled in the first few years of business, and currently stands at 40 per cent year-on-year, all rugs pass through Tameslouht for final checks, as well as the washing and surface burning that are part of the cleaning and softening process. After the rugs are hosed-down, they’re left out the back of the building and on the roof to bake dry in the North African sun.

Wright and Lobo-Navia’s model clearly differs from the often-extractive relationship in which Western companies come to developing countries simply because labour is cheaper. Alongside hiring people, the pair has also clearly committed to place. Both have been learning French and Moroccan Arabic, known as Darija, with Lobo-Navia renting a villa a 10-minute drive away from the HQ and Wright based in Marrakech (when he’s not in Barcelona or New York).

Both admit that bringing staff into the office wasn’t easy at the beginning due to cultural differences. But it has also proved a game changer. Traditionally, Moroccan weavers work at home or in small cooperatives near where they live, having to source their own yarn and find a market afterwards. At Beni, five buses a day bring people from Marrakech and villages to the office, and Beni’s founders have made sure that there is a real possibility for those coming onboard to work their way up from a beginner to a maallema (master). “In other facilities it’s hard to find young people,” says Afaf Chouhaidi, Beni’s director of operations. “But in the past few months we have had 10 young weavers join. There’s a career path.”

Lobo-Navia says that the HQ is all about building a work culture. “Our vision is unusual,” he says. “It’s community, it’s collaborative.” Alongside the couscous Fridays organised for the team, and the annual go-karting attended by the hyper-competitive washing and packing men, each weaver also gets a chance to make their own rug, all part of giving back to people who are used to making for others rather than thinking about a design for their own homes. Clearly the Beni founders want people to relish coming to work and value a craft that has sometimes been under-appreciated in Morocco.

Last year, the company signed with bricks-and-mortar retailer, Design Within Reach, becoming available in its 65 outlets throughout the US. Beni had to ramp up production to provide inventory when previously the model had been entirely made-to-order. And while it was stressful, they got the job done. When the shipment was finally complete in the early hours of the morning, Lobo-Navia and Wright sent a dkakiya music troupe to the HQ to serenade employees as a thank you.

With experimentation on the horizon, including a soon-to-come denser weave – and possible extension to another building in Tameslouht as the rug collection of over 240 designs grows – Beni wouldn’t be where it is without 66-year-old maallema Rachida Ouilki, whose quietly strong gaze suggests that she may share some of the tenacious qualities of her employers. Weaving since the age of 10, she says she is happy to teach new people coming through Beni’s doors the craft. “The weaver should love what they’re doing,” she says from a shaded area in the back patio. Does she? “Too much.”

benirugs.com

2.

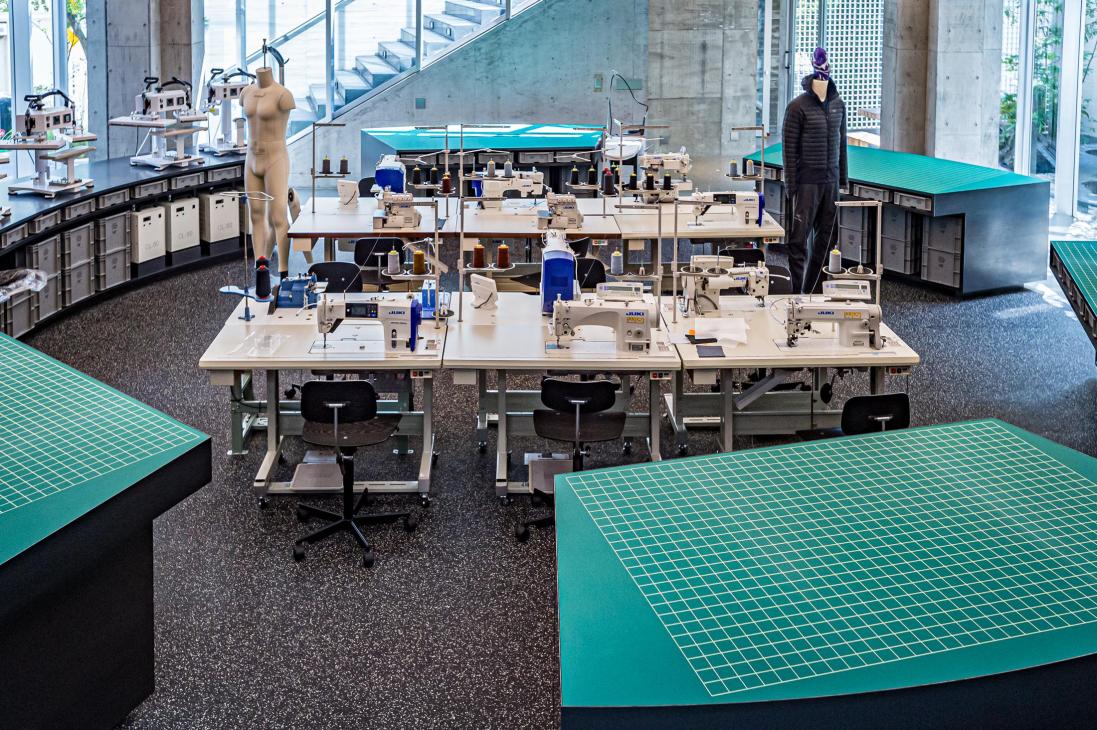

Arc’teryx

Tokyo, Japan

“There’s such an amazing connection between the brand and Japan with regards to the simplicity, beauty and innovation that we love,” says Katie Becker, the chief creative officer of Vancouver-based outerwear company Arc’teryx. She has just overseen the opening of the brand’s new outpost in Tokyo, its first overseas. Renowned for its minimalist, high-performance design, Arc’teryx worked with Torafu Architects to reimagine a concrete-and-glass building in the Daikanyama neighbourhood. Its primary aim is to function as a base for operations and community-building in Japan.

But unlike an ordinary creative workplace, the office has room for pattern makers and sewers to work on new ideas. Additionally, the basement, which doubles as an events space, contains a cutting room that’s equipped with materials and tools. Here, the Arc’teryx team can rapidly prototype and test ideas, speeding up the production process. “This is called a creation centre because we can actually make things here,” says Becker. “There are sewing machines and steam-tape machines. We can make a waterproof jacket in a day and go outside to test it right away.”

For Arc’teryx employees who aren’t out in the field exploring new concepts, the building has been designed to welcome the elements. The roof is an open garden area inspired by both the mountain landscapes of British Columbia and Japan’s rich forests. Here, seating made from Yanase cedar from Kochi prefecture has a circular form to encourage conversation and creative back-and-forth.

“We had this concept of creating a connection between inside and outside, the surrounding city and nature, as well as a place that is enriched by elements such as technology, culture and nature,” says Torafu architect Koichi Suzuno. The interior is filled with mountain-inspired artworks while one double-height wall is lined with Japanese craft and design, alongside vintage Arc’teryx jackets and mountain kit. “The wall is designed to provoke discussion and show the brand in context by displaying items from Japan with pieces that convey Arc’teryx’s history and philosophy,” says Suzuno.

arcteryx.com; torafu.com

3.

Giopato & Coombes

Treviso, Italy

“It was a classic romance,” says Cristiana Giopato, the co-founder of leading lighting company Giopato & Coombes. She tells monocle that she met her husband, UK-born Christoper Coombes, while on an Erasmus study programme in the 1990s. Today they work from an elegant 18th-century villa in the city of Treviso in northern Italy, designing and producing lighting pieces for hotel lobbies, jewellery shops and apartments worldwide.

After starting their careers in Milan – Giopato with Patricia Urquiola and Coombes with George Sowden – and working there for a decade, the duo felt that something was missing. “We wanted direct involvement in projects,” says Giopato. “In 2014 the time seemed right for us to bring everything in-house, to have a vertical model and become our own brand,” she adds, looking out over the villa’s lawns to a large former stable building that they have recently converted into a cavernous workshop and office space hosting 38 staff.