The Forecast

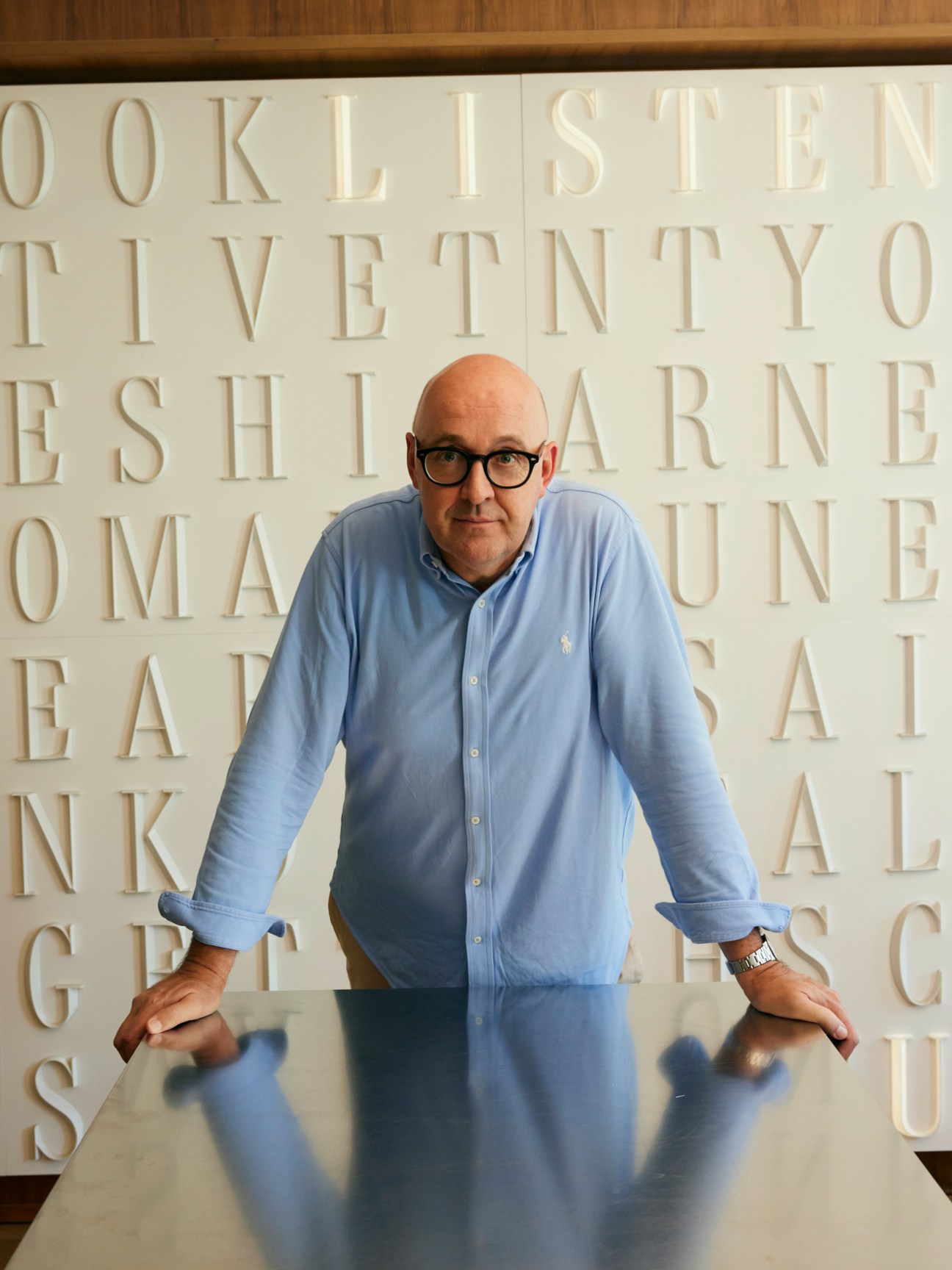

Interview: Alpine CEO Philippe Krief’s driving ambition

Waiting at a red light is a rather dull occasion – but not if you’re at the wheel of an Alpine a110 R and it happens to be playtime for the children in a nearby schoolyard. Then it becomes a moment of happy pandemonium, as excited faces swarm the fences and thrilled shrieks fill the air. As Monocle experienced on a recent drive just outside Paris, little can diminish the thrill of driving this diminutive sports car.

Alpine has been part of Renault since 1973 and is best known for its achievements in 1960s and 1970s motor racing. After remaining dormant for more than a decade, it was revived with a concept car in 2012; this led to the launch of the a110 “berlinette” five years later, attracting plenty of buzz. Then, in 2021, Renault rebranded its Formula 1 team as Alpine. With the release of a slew of limited editions and faster variants, commercial success was assured: Alpine sold 4,328 a110s in 2023, making it the bestselling two-seater sports car in Europe.

With the EU’s effective ban on new combustion-engine cars coming into effect in 2035, Alpine is now embarking on a major transformation. By the end of the decade, it hopes to offer a full range of electric vehicles (EVs) and reach revenues of €8bn. This expansion began with the unveiling of the Alpine a290 last summer – a sporty riff on the Renault 5 that will start deliveries in early 2025.

At the latest Paris Motor Show, Alpine’s CEO, Philippe Krief, set out the next steps of his plan, previewing the Alpine a390 Beta concept car, an electric SUV. Here, he tells Monocle about the road ahead.

Tell us about this new era for Alpine.

Our plan is to make six or seven vehicles by 2030, with an expansion into Asia and the US. We’ll have about one new car per year and the models will fall into two pillars. The first is that of two-seater sports cars, such as the a110 – maybe a two-plus-two-seater too. The other will be cars designed more for everyday use but still linked to the brand in terms of sportiness, exclusivity and strong design. The a290, the a390 and probably a future third car will fall into that pillar.

What guides you as you evolve into a global, all-electric brand?

When you know where you come from, you know where you’re going. Alpine’s founder, Jean Rédélé, was one of the only creators of great automotive brands not to name his company after himself. He called it Alpine to express the feeling of driving along winding roads in the Alps. All of our models have exuded this feeling of lightness, this pleasure, this simplicity of driving. On the other hand, if we want to establish ourselves in a robust, lasting way on the market, we have to increase our penetration a little bit, in terms of customers and markets. The key is to transcribe our DNA into all of our vehicles, especially those with broader appeal, and sprinkle them with French know-how, elegance, exclusivity and luxury.

What are the key challenges when it comes to creating a battery-powered vehicle that invokes all of these things?

A sports car is a car that responds well to all of the inputs of the steering wheel, accelerator and gearbox, and gives you a certain acoustic emotion. Electric technology ticks a few of those boxes but there are lingering questions about response time, lightness and acoustics. When it comes to response time, it’s possible to give an EV a completely natural behaviour through the integration of batteries low enough on the car to bring down the center of mass, and so on. The a390 that we are developing demonstrates this: it will have three motors, one at the front and two at the back. We have proof that we can give the perception of lightness despite the weight of the batteries.

The second aspect is the acoustics. Simply reproducing the sound of a combustion engine would be easy but that would amount to a refusal to enter this new era. The objective is to make the harmonics of the electric motor audible, so that you can sense the car’s behaviour through its sonic feedback.

A290 in figures

Battery range:

380km

0km/h to 100km/h:

6.4 seconds

Seats:

5

Boot capacity:

326 litres

Price:

From €38,700

As you expand into a global brand, will you stick to your model of producing all of your vehicles in France?

We will take it step by step. The a290 is produced in Douai; the a390 will be produced in Dieppe, just like the a110. So, for the moment, we are in France, both in terms of production and development. But we’re in the process of expanding our network all over Europe. We will tackle Asia too and distribute our cars there less discreetly than we do today. We sell the a110 R in Japan but it’s still quite limited.

How does motorsport fit into Alpine’s new plans?

It remains important to us. Alpine’s DNA is motor racing. It’s also a key brand vector and we use motorsport to make ourselves better known. Plus, it’s one of Alpine’s roles in the Renault Group to be at the vanguard when it comes to innovative technologies.

You’re the CEO of Alpine but also the technical director of the Renault Group. How do you see the role of software in the automotive industry?

The software revolution is, above all, a hardware revolution. Ever smaller and more capable microprocessors have made it possible to integrate supercomputers into vehicles. About 10 years ago, there were 60 to 70 “little brains” inside a vehicle.

Today we have three or four – even small supercomputers that manage everything. So we can be more responsive when we make a modification and be completely in control of what happens. Controlling three motors on a car almost in real time to make its behaviour smoother is no longer science fiction. That’s how we’ll ensure that a bigger car can offer the same feeling of lightness as an a110.

Car enthusiasts can be sceptical about technical innovations. How will you convince them to go electric?

We won’t force them. A few years ago, steering on cars was manual, so there was no assistance on the steering. When we switched to hydraulic power steering, there was pushback. But after a short while, it was over. Then we moved on to electric power steering. Again, people said, “Oh là là.” Now few still complain about it, as we kept the advantages of the old technology but added something. Here, it’s the same thing: we’ll keep the advantages of a sports car but add the more serene atmosphere of an electric car. And we’ll add performance that is incredible because the power density of an electric motor means that it uses less space and has much more force. Even the enthusiasts will appreciate it.

Alpine’s milestones

Founded:

1955

Renault becomes majority shareholder:

1973

HQ:

Dieppe, the birthplace of founder Jean Rédélé

2023 sales:

4,328 cars

Notable motorsport milestones:

World Rally Constructors Championship winner, 1973 (a110)

24 Hours of Le Mans overall winner, 1978 (a442 B)

Formula 1 Hungarian Grand Prix winner, 2021 (a521)

Paris’s top five sando shops

Bread is serious business in France. Some six billion baguettes are sold here every year – most baked in the ovens of 35,000 independent boulangeries, according to the Confédération Nationale de la Boulangerie et Boulangerie-Pâtisserie Française. On average, each of these shops serves some 300 customers a day.

France is also obsessed with Japan: it is the biggest overseas market for manga and Europe’s largest consumer of sushi. Japanese entrepreneur Michio Hasegawa and his business partners put two and two together and gambled on selling shokupan, the pillowy Japanese milk bread, to a hungry Parisian market.

On Rue Rambuteau in Le Marais, Carré Pain de Mie specialises in feather-light milk bread loaves and Japanese sandwiches. Classic sandos such as the creamy tamago egg filling and the tonkatsu (fried pork) are just some of the Western-influenced yoshoku classics that arrived in Japan following the US occupation in 1945. Its sando du jour runs the gamut from teriyaki chicken to foie gras terrine to show off the culinary confluence of two food-obsessed nations.

“The success wasn’t immediate,” says Haruki Ishiguro, the head baker at Carré Pain de Mie of the restaurant that opened in 2017. “But little by little we started to get more and more customers.”

When monocle visits, the crowd is as eclectic as the sando variations on offer: there’s a Japanese customer eager to take home a fluffy hunk of comfort food, wedged between a group of tourists and a family waiting for a table. In the pale-wood dining area, couples nibble shokupan crusts, offered as a side alongside the crustless cuboid-shaped sandos.

Carré Pain de Mie isn’t the only shokupan specialist whose fortunes are rising. At L’Atelier Sando on a quiet street in the 18th, lunchtime patrons of every stripe are similarly hungry: some in designer clothes, others in hard hats and high- visibility vests.

Louis Ricard opened L’Atelier Sando after taking over his parents’ French bakery when they retired. The site has retained a French touch but the cooking now is Asian-inspired and the window displays feature Japanese melon cakes and distinctive and colourful lychee and yuzu Ramune soda bottles.

“I worked in Japan and discovered sandos there,” says Louis, a former chef at l’Hotel Particulier Montmartre. He says that the pandemic’s shake-up of the restaurant industry made him want to reclaim the family bakery and strike out on his own with something less tested. “My brother is also a baker and pastry chef, so we recovered all the equipment here and started making sandos in-house; everything, including the bread.”

Other food entrepreneurs also saw the opportunity to follow in Carré Pain de Mie’s footsteps at that time. “My business partner already had two izakaya restaurants in Paris,” says Benjamin Trémoulet, co-owner of Soma Sando, another post-pandemic addition to the sandwich scene, referring to Japan’s version of an informal pub serving small plates. “During the lockdown, izakayas were not successful because small plates don’t travel well so didn’t work as a takeaway option.”

Going from izakaya to sandos proved so successful that Trémoulet and co-founder Marwan Rizk decided to open a cosy, wood-clad site on the southeastern corner of the Jardins du Luxembourg. Its best-seller? An award-winning Tori Sando, a karaage chicken sandwich with tartare sauce, crisp carrot and cabbage, and sharp pickles.

For other chefs, the informality of the simple sando is democratic and yet offers some space to be creative with the culinary similarities and differences between Japan and France. Chef Walter Ishizuka, who trained under Paul Bocuse and had a decades-long career in fine-dining restaurants across the world, opened Yabaï Sando near the carrefour de l’Odéon. “My father is Japanese and my mother is French,” Ishizuka, who grew up in Lyon, tells monocle over coffee at his dark-walled restaurant bedecked with paper pendants. “At school I didn’t have jambon-beurre sandwiches in my picnics; I had white-bread egg sandwiches. There’s a [personal] history there that I wanted to revisit.”

Ishizuka’s take on the sando expands beyond his childhood staple. The combination of his Michelin-starred-restaurant experience and technical mastery mean decadence in the form of his Wagyu beef sando and experimentation seen in products including his black sando bread coloured with burnt vegetables.

Success for these sorts of restaurants is never assured. “In the beginning, I doubted whether it could be accepted by French people,” says another sando aficionado, Kaito Hori, who opened Benchy on Rue du Cherche Midi. The former fashion designer still tries to bring together his branding experience with alluring shoots and visuals but it’s the quotidien joys of running a bakery that he enjoys most. “We’re happy because we have so many regulars coming nearly every day to have sandwiches.”

As with every food movement and seemingly fresh idea, many see echoes of older trends and more entrenched customs in Paris’s embrace of the sando. “The success is first and foremost about the enthusiasm of France’s younger generation for Japan,” says Michio Hasegawa. But, says the septuagenarian, there’s nothing entirely new in it. “It’s the same enthusiasm you saw for France among the youth of my generation in Japan back in the 1960s.” —

Get a slice of the action here:

Carré Pain de Mie

5 rue Rambuteau 75004

L’Atelier Sando

169 rue Championnet 75018

Sôma Sando

62 rue de Vaugirard 75006

Yabaï Sando Odéon

3 rue des Quatre-Vents 75006

Benchy

50 rue du Cherche-Midi 75006

Laser focus: How anti-drone systems are redefining warfare

In a nondescript industrial park on the outskirts of Canberra, the future of warfare is being redefined. It might be thousands of kilometres from any active conflict but the whirr of movement on the warehouse floor at Electro Optic Systems (eos) tells its own story. eos develops and manufactures a range of military and space-related technology but in recent years has become known for one thing: anti-drone systems. Its pre-eminent status in this nascent field has been underlined by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, where more than 100 eos products are in use every day. As drones become cheaper and more deadly, nations around the world are racing to secure technology that can counter the threat, meaning that eos is suddenly in high demand.

On the factory floor, dozens of anti-drone systems are packaged up ready to be delivered to customers, while others undergo testing to ensure that they can operate continuously in the most challenging of conditions: some are in temperature chambers at a balmy 60c, while others are set to a frosty minus 32c. In the early 2000s, the US was the only military with high-quality drone technology – the Predator unmanned aerial vehicle (uav), which was deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq. But since then, as the technology has proliferated, its costs have plummeted. “Now it’s an asymmetric form of warfare,” says eos’s cfo Clive Cuthell, whose thick Scottish accent belies his 30 years in Australia. “You can spend $1,000 on a drone and attack an asset that costs $10m, $100m, even $1bn. You no longer need to spend a fortune to attack high-value targets.”

Dealing with one drone is hard enough but the low cost means that an enemy can now launch 100 or even 1,000 drones at a time. “It’s very difficult to deal with that oversaturation,” says Cuthell. “You can overwhelm almost any defence system.” This is a tactic that was deployed in 2024 by Iran’s air force against Israel. One of eos’s newer systems, the Slinger, which went on sale in 2023, has seen great success in Ukraine, where 200 are currently deployed in the field, many of which were purchased by Western powers as military aid. Weighing fewer than 400kg, the Slinger can be mounted on the back of a pick-up truck and has a radar and camera system that can detect and neutralise even the smallest drone. Its demonstration video on the eos website is captioned, “No one kills drones like eos.”

Most of the company’s anti-drone bestsellers feature “multi-layered” responsive weaponry – meaning that operators have a selection of ways to take uavs out of the sky. For example, a battlefield anti-drone platform like the Slinger might have a third-party missile system to take down longer-range drones; a built-in laser to “blind” drone sensors; or a chain-gun, which acts as more conventional anti-aircraft artillery. But companies such as eos are engaged in a literal arms race when it comes to countering drones.

Initially, “soft-kill” mechanisms, such as jammers and spoofers, could easily neutralise uavs but militaries have adapted them to counter such interference, meaning that “hard-kill” methods, which destroy the devices completely, have become essential. “That provides a strong tailwind for us to commercialise our innovations,” says Cuthell. As he inspects a new order bound for Kyiv, eos vice- president of international programmes Glenn McPhee, a former Australian army officer, says that he was attracted to the company both for the “cool Australian technology” and “helping Nato soldiers defend themselves”.

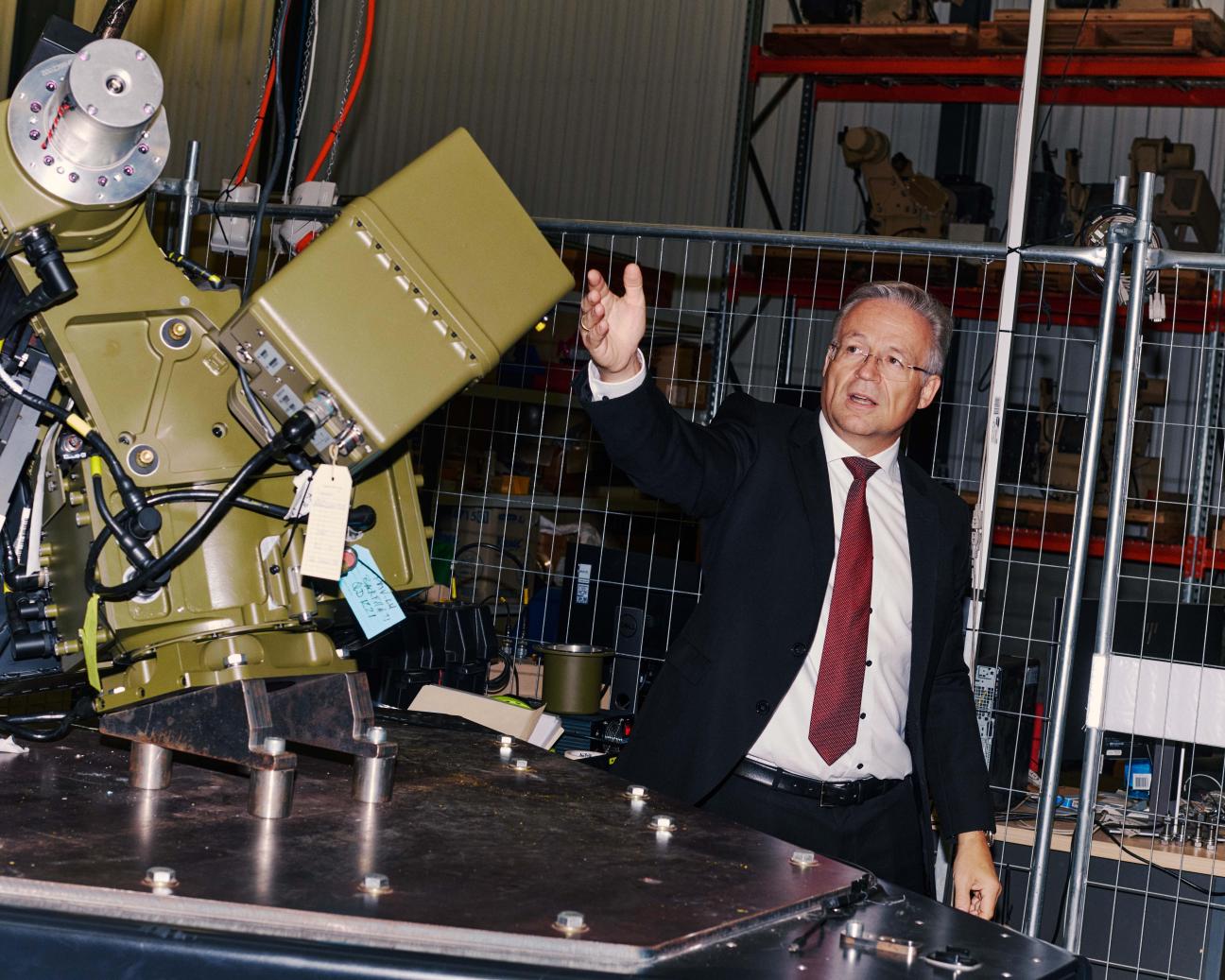

eos began life as an Australian government research institute with a focus on the space sector, including optics and laser technologies. In the 1980s the firm was incoroporated as a private company and, in the early 2000s, listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. Ben Greene, one of its original founders, is a world-leading space physicist who began working in the sector not long after the first moon landing. Today he serves as eos’s chief innovation officer. Perhaps reflecting its academic origins, eos has always excelled at research but traditionally had less success on the business side of things. “It was a strong scientific, engineering, military and academic culture that had invented many things – but not commercialised them,” says Cuthell.

The arrival of Andreas Schwer in 2020 signalled a turning point. A bespectacled German with grey hair and a firm but understated manner, Schwer has decades of experience in the space and defence sectors, including at Airbus and Rheinmetall. In 2017 he was asked by Crown Prince Muhammed bin Salman to build up his country’s defence sector by taking the helm at Saudi Arabian Military Industries, where he stayed for three years. “When I was working in Saudi, we had selected eos as the partner for high-energy laser-weapons systems and I had done a deep due diligence,” he says. “I had found out that the company had a huge innovation and intellectual property rights portfolio but is not the best in terms of commercialising it. We wanted to take what was sitting on the shelf in terms of innovation and make real-life products.”

The arrival of new management coincided with significant geopolitical shifts – the Ukraine war, later the conflict in Gaza and rising tensions in the Indo-Pacific. All have led to a surge of interest in eos’s products. “Investment in defence by national governments is higher than it has ever been,” says Cuthell. “Defence is an industry where technology really matters. The technological edge can often be decisive in conflict – and we’re at the cutting edge.”

Part of the leadership team’s ambition is to transform eos into a bigger global enterprise. The firm already has four offices around the world, operates in almost 20 countries and is growing its manufacturing operations in the US and the uae (where Schwer, who became ceo in July 2022, has a base). In 2024 it opened a laser-innovation centre in Singapore. Schwer hints that increased onshoring requirements and supply-chain concerns mean that joint ventures and localised manufacturing will play a big part in eos’s future. “Part of the strategy is to become a truly global player,” he says. Canberra is not known as a hi-tech hub but the Australian capital has a strong university sector (eos sponsors two research chairs) and a large defence industry, with the Australian military’s headquarters just 20 minutes down the road from eos. The buzz of activity on the factory floor suggests that Schwer’s mission has been a success so far. Revenue to December 2023 was up almost 60 per cent year-on-year; while in the first half of 2024, it has almost doubled again. Schwer insists that the push to take products to market is not coming at the expense of ongoing research. “Research was the core,” he says of eos’s history. “And it still is.”

eos’s anti-drone technology has the capability to be fully autonomous, though, for now, many of its customers use human operators. The company’s systems can track and identify drones within a 5km radius, drawing on a database of almost 600 drone types constantly updated by a partner firm. The technology can identify the location and model of the drone, and whether it is friend or foe – an increasingly important function as both sides in many conflicts deploy their own uavs. But armed forces are not the only users of this technology. Drones increasingly pose a domestic risk – whether deployed by local agitators or international terror groups. eos systems are being sought out by organisers of major events. “That has started and will become the standard in the future,” says Schwer. He is tight-lipped about specific civilian deployments. “That’s classified.”

Space also remains a major focus. Not far from the factory, eos shares the Mount Stromlo Observatory with the Australian National University. The firm’s laser technology can track objects in orbit down to the size of a coin, an important capability as the planet’s stratosphere becomes more cluttered with debris. “There is nobody, outside the US, that has this kind of highest accuracy tracking of objects in space,” says Schwer. “So one major application is that we track debris and provide anti-collision warnings to any kind of satellite operator. With our latest evolutions in technology, we can also move space debris, actively avoiding collisions.” Such technology also has military application. “In the long run, war will be decided in space,” he adds. Schwer pulls up a photo on his phone showing a bright-green laser beaming into the night sky. “This is not Photoshop,” he says. “This is how we use laser systems to track objects in space.” Though separate arms of the business, the anti-drone and space sectors are deeply interconnected. The success of the former builds on eos’s decades of research in monitoring objects outside Earth’s atmosphere. “We can track any object in space,” says Schwer. “So it’s easy to downscale this sensor technology, to see further and better than anyone else on the battlefield.”

It is a long way from Canberra to Kyiv. But the cutting-edge technology being manufactured at eos is playing an essential role as Ukraine seeks to defend itself. The conflict in the country has demonstrated in real-time how critical drones and anti-drone technology are to modern warfare – and is setting the tone for conflicts to come. Schwer was one of the first foreign business executives to travel to Kyiv after the war began. He vividly remembers his initial visit: crossing the Polish border at night, in the snow, on an arduous rail journey to meet Ukrainian officials. “Those times were challenging,” he says. “We spent many nights in the bunkers. Many meetings had to be interrupted because of missile alarms.” He laughs and says that the trip was almost derailed by difficulties securing travel insurance. “It was super expensive,” he says. But for eos, the demonstration of commitment to supplying Ukraine with market-leading defence technology was worth every cent. “They will never forget about your engagement and commitment in the early days,” he adds. “You came to them when you were exposing yourself to significant risk.”

Schwer and his team have been back many times since – he estimates that every second month an eos representative is in Kyiv, or often even closer to the frontlines in the east of Ukraine. “We’ve established very close contact to the leaders, to the commanders, to the officers at the frontline, to get first-hand experience and have those lessons learned introduced to our ongoing development programmes,” says Schwer. That information feeds directly into product development: eos has simplified systems to make them more user-friendly in the field. “We are learning day by day, week by week.” The eos boss cites the example of the Abrams tanks donated to Ukraine by the Americans. “The US has lost more than half of its donated Abrams in Ukraine by drone attacks,” Schwer says. The remaining tanks have been removed from the battlefield, awaiting an upgrade; eos systems are being trialled for possible integration.. Sometimes videos appear on social-media platform Telegram of eos weapons protecting key Ukrainian infrastructure from Russian drone attacks. As soldiers cheer in the background, half a world away, Schwer’s team is energised. “That makes us proud.” —

EOS’s other hot products

Part of eos’s recent success has been built on the integration of its different systems – the anti-drone technology can integrate remote weapons systems, which draw on the success of laser products.

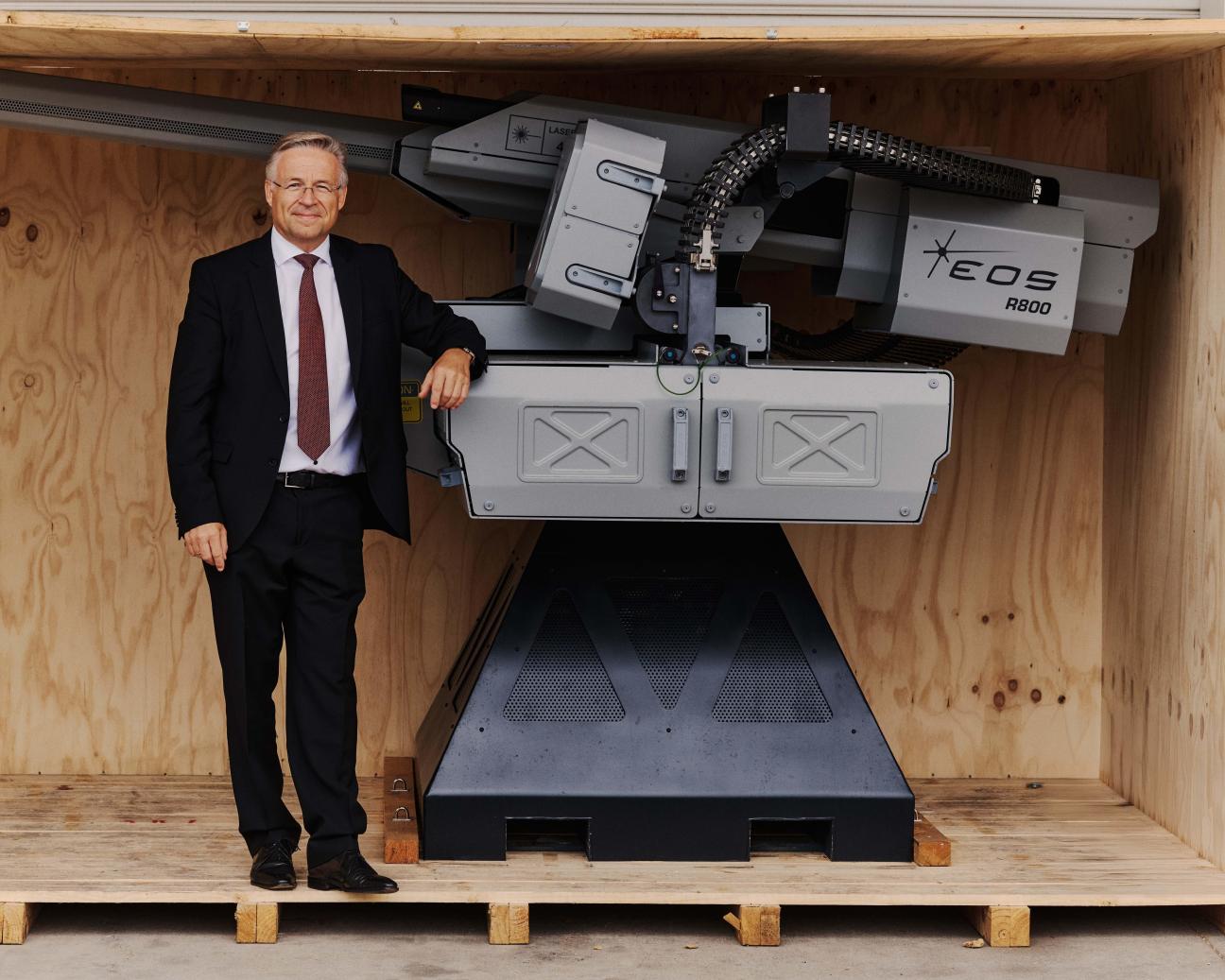

Remote weapon systems

eos’s range of remote weapon systems combine heavy firepower with advanced surveillance capabilities. These include the r400, a lightweight model that can be mounted on trucks, tanks and ships; the mid-range r600; and the heavy-duty r800, which has a cannon and machine gun.

Lasers

In September, eos announced it was finalising deals for its high-energy-laser weapons systems to two undisclosed international clients, in what is believed to be the first export sale worldwide of a laser weapon at that power domain. “We will be the first mover,” says Schwer. The laser weaponry can engage drones between 200m and 3km away.

Space

eos has a range of space-related products and services, including satellite laser ranging stations, which track satellites in orbit, and space domain awareness, monitoring objects in space. One eos brochure describes the technology as “space intelligence for battlefield commanders”.

Why small electric vehicles are making a big impression in Cuba

Havana’s traffic might be best known for its brightly coloured classic cars – stately Chevrolets imported from the US before Cuba’s socialist revolution in 1959, boxy Soviet-made vehicles that followed during the Cold War and an array of antique Fiats, Minis and others. But increasingly, commuters are opting to use a new crop of small electric vehicles (EVs). These include dinky electric cars, tricycles and cargo trucks, as well as electric bikes and scooters, which are all accelerating the shift from the classic to the contemporary when it comes to getting around.

“It is only very recently that people realised that it’s much better to have some kind of electric vehicle in Cuba,” says Mark Manger, a professor of political economy (with a speciality in contemporary Cuban history) at the University of Toronto. “Because you don’t have to rely on the infrequent deliveries of fuel or contend with volatile gas prices.”

Demand has also been fuelled by these vehicles’ relatively low price tags. “Another big selling point is that these EVs require such little maintenance,” said Manger. “Importing parts to repair a classic car in Cuba is extremely difficult; people often have to improvise and make replacement parts themselves. So it’s much better to have a relatively new electric vehicle.”

Their diminutive size means that they can be plugged into a domestic socket and charged with ease. The distance that they can cover is a draw too. “You can drive 100km on one charge, which is sufficient for wherever you need to go in Cuba,” says Manger. A recent change in import laws means that private individuals can now import electric cars. China’s canopied three-wheelers by Onebot and Lesheng’s four-wheeled, two-seater models are particularly popular, while similar four-wheelers are produced by Japan’s Kimura.

Domestic production is ramping up too. Some 23,000 EVs were manufactured between 2020 and 2022, according to government figures. At Vedca, a miniature-vehicle maker based in Havana, the growth in demand has accelerated the development of new lines. These include miniature tractors and industrial vehicles designed for heavy lifting, which are currently in their testing phases.

The green petrostate: Can Norway become carbon neutral?

It’s an unusually bright day in Bergen, Norway’s second-largest city, as monocle joins a bus of cheery government and business delegates up the North Sea coast. Our destination is the small island of Øygarden and Northern Lights, a carbon capture and storage (ccs) facility whose opening represents a great leap forward in the country’s aim to be a low-emissions society by 2050. Norway’s prime minister, Jonas Gahr Støre, has preached the necessity of cutting greenhouse gas emissions and protecting the natural environment, pitching his nation as a role model. And he’s right. In 2024, 98 per cent of Norway’s electricity grid came from renewable sources, mostly hydropower, while electric vehicles (EV’s) account for more than 94 per cent of new car registrations, compared to 12 per cent in the EU.

The problem is, depending on who you speak to, the Nordic country is either a green icon or a shameless petrostate. Though it is unarguably a green trailblazer, its decarbonisation is built on the profits of oil and gas extraction, 90 per cent of which is sold abroad, a figure that represents 62 per cent of the country’s total export value. This healthy earner has become a windfall in recent years as a result of both Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine – after which Norway became the continent’s largest supplier of natural gas and second-largest supplier of oil – and worldwide inflation. By the end of 2022, petroleum revenue surged to €125bn, five times more than in 2021; in 2024, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund hit €1.7trn. “We are proud to supply critical energy to Europe during this challenging time,” says Terje Aasland, the country’s energy minister. But pride and guilt are two sides of the same coin in Norway’s oily history and given accusations that the country is profiteering from the world’s crises, the guilty side is growing. The International Energy Agency (iea) insists that further Norwegian drilling is incompatible with the Paris Agreement. So how will Oslo comply with a treaty – that it has enthusiastically agreed to – at the same time as investing a record €22bn in its oil industry? Its answer is twofold: a hefty €1.9bn investment in ccs and a bet on its untapped resource of rare-earth minerals.

Fifty minutes after departing Bergen, 12 giant metal tanks rise up on the horizon. “This is a great day,” says Aasland, beaming as he gestures towards Northern Lights. “This project proves that we can capture co2 and store it permanently and safely under the seabed.” Opened in 2024, Northern Lights is the world’s first commercial ccs facility. The idea behind the technology is to capture carbon emissions before they enter the Earth’s atmosphere, liquify them and then pump them into the ground, or, in Northern Lights’ case, a reservoir 2,300 metres below the seafloor and 100km off the Norwegian coast.

The country’s government is pitching ccs as a redemption story, one in which Norway’s fossil fuel extraction can benefit it and the world’s green transition. “Ever since we discovered oil, our continental shelf has been mapped in great detail,” says Torgeir Stordal, director general at the Offshore Directorate, the government’s petroleum regulator agency. “Not all reservoirs contain oil and gas; some just have water. That is where we can inject co2.” Norway has already pumped at least 25 million tonnes into the crust of the North Sea over three decades and now aims to build a full-scale commercial infrastructure, selling storage to European customers to help their countries offset rising carbon taxes. “I’m convinced that in some years we will have a commercial industry in the European market,” says Aasland.

The crowd at Northern Lights agree – but is this the whole truth?

The tone is less optimistic at the Ministry of Climate and Environment in central Oslo. monocle bustles through security alongside reporters, opposition politicians and environmentalists to witness the unveiling of the Green Book, the part of the annual state budget that outlines the country’s progress towards its climate targets. When climate and environment minister Tore O Sandvik takes the stage, a sense of disappointment quickly clouds the room. Norway has set ambitious goals to reduce emissions by 55 per cent by 2030 but, if current policies continue, that number is looking closer to 26 per cent. In comparison, neighbouring Sweden has already reduced its emissions by 35 per cent. And, if there’s anything worse to a Norwegian than failure, it’s losing to the Swedes.

“We are a little delayed,” says Sandvik. “But we will reach our climate commitments together with the European Union.” The government’s rather unambitious plan lies in the EU’s Emissions Trading System, which enforces a punitive carbon cap on polluters and lets them purchase allowances from each other to balance the score. But there is a problem: the future prices and quantity of these allowances are unknown, making the strategy a gamble. Despite accounting for at least a quarter of Norway’s emissions, Sandvik is adamant that phasing out oil and gas extraction is off the table. “Europe needs all the oil and gas they can get from Norway in this situation,” he says. Terje Aasland defends this position by stressing that Norwegian oil is greener than that produced by other countries. “Thanks to strict climate policies, Norway produces oil and gas with much lower emissions,” he says. Indeed, Norway was among the first countries to introduce a carbon tax in the 1990s, and the first in the world to build fully electrified oil platforms. But whether its product is the lesser of two evils, its own forecasts highlight the need for entrepreneurial alternatives to fossil fuels. And it might already have such alternatives right under its nose.

It is a misty morning in Ulefoss, a settlement of 2,600 in Norway’s rural Telemark region. The town’s unassuming face belies a potential jackpot deep below the ground. In June, a company called Rare Earths Norway (ren) confirmed that the volcanic Fensfeltet region contains Europe’s largest deposit of rare earth minerals. These precious gems (among them neodymium, praseodymium and 15 others) are essential to green technologies such as EV batteries and wind turbines. “We are completely dependent on these minerals to achieve the green transition,” says trade and industry minister Cecilie Myrseth. With no rare earths industry of its own, Europe relies on China for 90 per cent of its supply, leaving it vulnerable to geopolitical tensions heightened by the election of Donald Trump, who has promised to raise tariffs on Chinese imports while exhorting America’s European allies to do the same. Fensfeltet is estimated to contain 8.8 million tonnes of rare earth minerals, a number that dwarves the 18,000 tonnes imported to the EU in 2022. And with this figure expected to increase sixfold by 2030, it’s no wonder many in Norway are excited about rare earth minerals’ potential to steer the country away from fossil-fuel extraction.

One might imagine, therefore, that ren is swimming in government subsidies but when Myrseth and Aasland sit down to a roundtable with stakeholders, the tone is as murky as the weather. “Where is the willingness to invest?” asks regional geologist Sven Dahlgren. “If things stay lukewarm, we won’t get anywhere.” For decades, Dahlgren mapped Fensfeltet almost single-handedly on local county funding. Since 2016, ren has conducted its work on just €14.8m of mostly private input. This modest budget means that geologist Gaute Magnushommen still manages ren’s thousands of drill samples at a defunct school. “We need impatient people,” Myrseth tells monocle, before addressing the government’s slow pace. “But we also have to do things properly.” ren did recently receive €5m in state funding for a pilot mine but there is no mention of Fensfeltet in the Green Book, and no government plan to help ren secure financial support from the EU.

Instead, the government has prioritised its deep-sea mining ambitions, which would involve extracting minerals such as cobalt, nickel and rare earths from the ocean floor. Scientists and environmentalists argue that the practice could devastate ocean ecosystems; many countries have called for a ban. Ignoring international sentiment, Norway raced ahead with plans for commercial deep-sea mining in January and the 2024 state budget earmarked €12m to accelerate things. “We have only opened our oceans for mapping and exploration, not mining,” says Aasland.

Critics fear that Norway will prioritise profit over sustainability. In Ulefoss, there is a sense that deep-sea mining is pillaging resources from a land-based industry that will be more environmentally friendly and is in greater need of state backing. “We probably have up to 10 times more rare earths at Fensfeltet than what has been estimated offshore, where the total area is 6,000 times bigger,” says ren’s ceo, Alf Reistad. At one telling moment in the meeting, Myrseth, who is responsible for the land industries, turns to Aasland, overseer of Norway’s deep-sea mining and oil. “I guess there is a bit more resistance on your side,” she says.

“There is nothing but resistance,” says Aasland, groaning.

The scene is symbolic of Norway’s struggle to become the green leader it claims it wants to be. Pressing ahead with more oil and gas drilling and a dubious offshore mineral industry, it has also adopted a timid posture towards greener ventures, while looking to ccs as a silver bullet, even though some have suggested it encourages carbon emissions rather than abating them. The debate strikes at the heart of Norway’s environmental identity crisis, and promises sleepless nights ahead for its avowedly green political leaders. —

Why the airship industry is on the rise again

You would be forgiven for thinking that the bubble had burst on the airship industry. Finnish company Kelluu, however, remains loyal to the sector. Based in Joensuu, eastern Finland, it operates what the company calls “the world’s largest airship fleet” and has a clear business case, as CEO Janne Hietala explains.

“We operate in a niche between drones and aircraft,” he says. “The former have a short flight time, while the latter are expensive, environmentally harmful and fly above the clouds.”

For what Kelluu does with its airships, clouds are a problem. Its business is imaging and instead of flying people from place to place, Kelluu’s airships photograph the Earth. With state-of-the-art cameras, they can capture incredibly detailed photographs of a wide area. “With just five of our airships, we are able to photograph the entirety of Germany with a level of accuracy that no satellite can match,” says Hietala.

In addition, its cameras can provide hyperspectral imaging, which its clients can use to monitor metrics such as humidity and temperature. The images can also be used to construct detailed 3D maps, or what the company calls “digital twins”. Clients are diverse and range from forestry companies that are keeping an eye on the health of the land and power companies monitoring the state of its lines in remote locations to urban planners who need to know how the traffic is flowing. The market that Kelluu is set to revolutionise is large. According to Hietala, the annual cost of monitoring critical infrastructure, such as electricity networks, is approximately €60bn globally.

“No other technology can achieve the same level of efficiency as airships can,” says Hietala. In an increasingly environmentally conscious world, the fact that Kelluu operates the airships with hydrogen, and thus without emissions, is another factor in its favour.

Hietala likens the company’s airships to satellites orbiting Earth. Unlike drones or helicopters, the airships don’t need human pilots and can be programmed to cover a certain area. “Their flight time is about 12 hours and all we need to do is have a flight-control centre that tracks where they fly,” he says.

But it has not always been smooth sailing, or floating, for Kelluu. It is doing something totally new and regulators are still playing catch-up. “All of our pilots have licences and have been trained to communicate with other air traffic,” says Hietala. “But sometimes the regulators still think that we just fly drones.”

The company’s airships usually fly at a maximum altitude of 150 metres and because of their snazzy silver bodies have startled the occasional onlooker more than once. “Quite often people call the energy number and claim to have seen a UFO,” says Hietala with a laugh.

kelluu.com

Other airship firms on the rise:

1.

LTA (Lighter Than Air) Research, founded by Google’s co-founder Sergey Brin, is building next-generation airships for human transportation.

2.

UK-based Hybrid Air Vehicles is developing passenger zeppelins that can stay airborne for up to five days and have a range of 4,000 nautical miles.

3.

Flying Whales is a French company developing cargo zeppelins that can carry up to 60 tonnes.

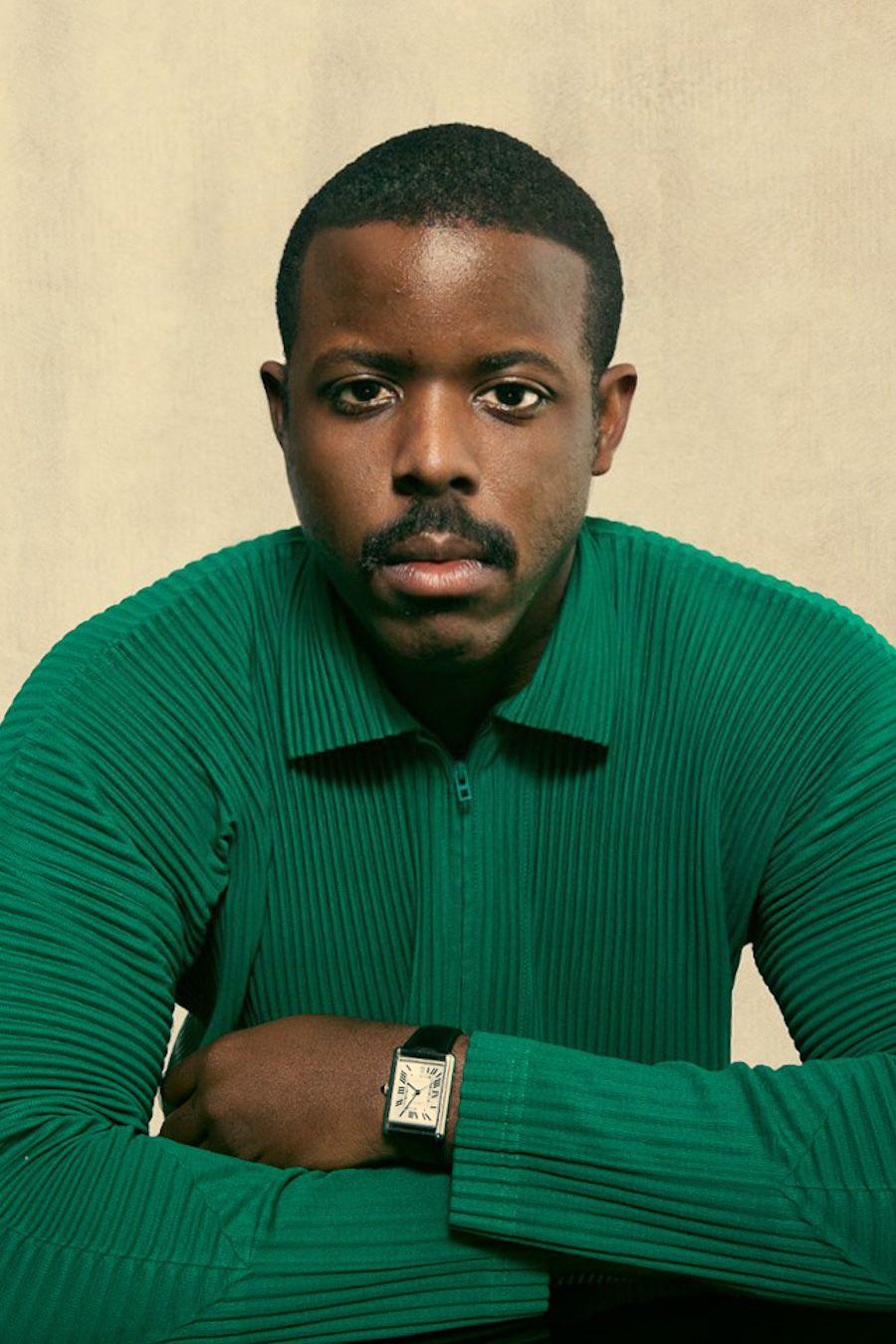

Interview: Nteje Studio’s Myles Igwebuike on exploring heritage through design

Based between the UK and Nigeria, designer Myles Igwebuike works in the field of diplomacy as a World Economic Forum Global Shaper. Through his practice, Nteje Studio, he collaborates with artisans in southeastern Nigeria to explore heritage through design – be it to reimagine a workout bench for Technogym or develop his line of sculptural wooden chairs. We talk to Igwebuike about his ambition to scale craft and design as soft diplomacy and how others can learn from his work.

Tell us more about Nteje Studio and working with artisans in Nigeria.

I work with local artisans and young designers. I’m a futurist, a young kid with a lot of ambition who thinks that he can change the world. When I go to Nigeria, I conduct a lot of design workshops and try to move the perspective of these young designers and artists from a space of scarcity to abundance. How can we replace a limiting mindset with a mindset that knows no bounds? My workshops are to do with looking at how we use materials that we have in our environment and within our locality. I am currently researching how to scale indigenous craftsmanship, especially woodwork and sculptures. From personal experience and from information that I’ve gathered on the ground, as well as from a diasporic lens, we need to look at how to scale up manufacturing, simplify it and continuously test materiality. What does it look like to replace and reuse? My dream is to create new economies within the Nigerian design industry.

Where do you position yourself within the design industry?

I like to question what design looks like by using cultural heritage as a vehicle to explore it. And this is not to say that all design needs heritage or nuance. But just making more space for it. My practise is about being around southeastern Nigeria and the social dynamics that can be found there. For example, for the last stool I made, I examined mythology and musical instruments to shape its form. My work outside creating beautiful objects is to nurture a community and explore concepts that bring people together. To reconnect with culture – and not necessarily African culture. The whole point is for you to be of any ethnicity or demographic and feel that you can create your own culture, or connect with it, wherever that is and whatever that is.

Live and learn

In a former cotton mill in the southwest corner of Venice, a group of international students has gathered in a classroom for a special guest lecture called Managing Waters. Projected onto a white screen at the front of the room, a slide reads: “The protection of Venice and its lagoon against flooding.” Francesco Musco, a professor of urban planning and deputy dean of research at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia IUAV, is keeping an eye on things through the classroom door’s round windows.

Musco has just completed a research project on the efficacy of Venice’s flood barriers, the Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico (Mose), which began operating in the lagoon in 2020 to ward off tidal surges. Off the back of these studies, he has called on colleagues in various disciplines to come and talk to his students. “The master’s programme in urban planning and transition is about making our cities more resilient to climate change,” he says, while walking Monocle through the halls of the old industrial building (the Sedi Cotonificio was renovated into classrooms, studios and lecture halls by celebrated mid-century architect Gino Valle when the university expanded in the 1990s).

It’s an educational ambition that’s seeing IUAV, which was founded in 1926 as Italy’s second public architecture school after Rome’s Scuola Superiore di Architettura, emerge as an appealing place for architects from across the globe to continue their studies. The university introduced Italy’s first master’s degree in urban planning in 1970 and today it continues to be a hub of innovation, attracting students who are keen to learn in – and from – a city at the forefront of climate change, mass tourism and cultural conservation.

At the forefront of this concept of learning from the city is Valeria Tatano. As a professor of architectural technology at IUAV, she is keen to get her students out into the city as much as possible. “Studying at your desk and at the library is all very well but in Venice there is a lesson to be learnt at every street corner,” she says. The previous week, she took a class to the Procuratie Vecchie in St Mark’s Square, a residence for public prosecutors built in the 1500s and recently restored by architect David Chipperfield. A short walk from the building, a small barrier has been erected around the square’s basilica to protect the 1,000-year-old church from moderate floods (at present the square finds itself under water some 60 times a year). “I can explain a million times how or why something is done but when students are able to see, touch, take pictures – then they have many more questions,” she says.

Seeing such work first hand is critical for architecture students who are moving into a professional world where environmentally minded approaches are key to project briefs. Built on a marshland in the centre of the lagoon, Venice has always had to find a balance between the urban and natural worlds. And it is a balance that is only becoming more important: since 2020 the Mose barriers have been raised 50 times, with some scientists predicting that, despite their effectiveness, the city could be under water in less than a century. Add to this the increased pressure on architects to design buildings that are in tune with the environment and it’s understandable why living and studying in Venice, where a changing climate is so visible, is increasingly appealing. Back on campus, Musco says that this is a key quality of the city that is attracting urban-minded architectural students. “Venice’s peculiarities make it very representative of many coastal cities.”

But it’s not just environmental problems that are strengthening IUAV’s educational offering; it’s the fact that every aspect of delivering a building poses a challenge in the city, from access to supply chains to connectivity beyond its islands. Here, buildings are battling sinking foundations (Venice is constructed on timber piles pushed into the loose mud and clay of the lagoon), while electricity, water and gas pipelines need to cross bridges and be hidden beneath pavements. Such topics are currently being unpacked in one of IUAV’s international architecture master’s programmes, where students from countries as varied as Ecuador, the US and Russia are working in groups to design an exhibition space in Ca’ Zenobio degli Armeni, a baroque palazzo. One of the challenges that students are being pushed to consider is how, in order to build the structure, construction materials would be transported through the canals. “It might seem obvious but studying in Venice is incredibly valuable,” says Michel Carlana, who studied architecture at IUAV and now teaches here, while also running his Treviso-based architecture practice. Bruno Tello Fernández, an architecture master’s student from Seville agrees. “Venice is one of the few examples of this particular way of life,” he says, while working on his design for the exhibition space. “Studying here helps you see how people adapt to different types of architecture [and ways of building].”

Building the future

Budding architects wanting to get hands-on experience and make a difference should look to these schools

For a profession with such a concrete effect on the planet, the institutions educating architects can get a little gobbled up by jargon and abstraction. Here are five schools, from Hong Kong to São Paulo, that put their students head on with real-world issues, teaching the next generation of architects and urbanists how to come up with sharp solutions – and build them too.

1.

Pratt Institute

New York, US

Good architecture depends on quality buildings and engaging public consultation and programming. The Urban Placemaking and Management master’s programme at Pratt educates urbanists of tomorrow in these softer skills, with a two-year programme that sends students out for extensive field work in neighbourhoods from New York to Havana.

pratt.edu

2.

Africa Futures Institute

Accra, Ghana

Founded by Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko in 2021, two years before she curated the Venice Architecture Biennale, the Africa Futures Institute is a place for postgraduate research with a focus on the Global South. Based in Accra, the school brings together leading practitioners from around the world who host workshops and lectures.

africanfuturesinstitute.com

3.

Aarhus School of Architecture

Aarhus, Denmark

Denmark’s only purpose-built architecture school is designed to discourage time spent in front of a computer. With open-plan studios and workshops for everything from carpentry to laser cutting, the three-year education equips students with the skills to construct not only models but real buildings too.

aarch.dk

4.

The University of Hong Kong

Hong Kong

One of the best architecture faculties in Asia is launching a new graduate programme in advanced architectural design in 2024, aimed at hands-on learning. Called The Building Society, the one-year master’s degree applies cutting-edge material and technological innovation to the construction of a building in a village in the region.

hku.hk

5.

Escola da Cidade

São Paulo, Brazil

Since it was founded in 1996 by an association of architects, artists and intellectuals, the Escola da Cidade – or School of the City – has educated many of Brazil’s brightest young urban thinkers. A key premise is the Itinerant School, which prods students to get out on the road and learn directly from the built environment.

escoladacidade.edu.br

Significantly, and important to IUAV’s plans, is the fact that the university brings urban planning and architecture together with courses in design, fashion and theatre. In the corridors of Sedi Cotonificio, as well as in the narrow streets that connect to the main university building in Sedi dei Tolentini (with an entrance designed by one of IUAV’s most celebrated former directors, Carlo Scarpa), the university’s 4,000-odd students can be seen carrying everything from rolls of sketches to architectural models and coat hangers. Tatano, who like most professors was also a student here, says that this holistic, design-oriented approach gives a richness to the university’s courses. “Being a small university means that we’re all constantly on top of each other,” she says. “But it means that someone designing a building is shoulder to shoulder with someone designing a skirt.”

In addition to learning from the city’s problems, IUAV is also seeking ways to solve them. High rents mean that most students can’t afford to live on the islands of Venice and must commute from the mainland but the ancient city is also in desperate need of newcomers: it has lost 120,000 residents since the early 1950s. Recognising that for the city to continue to be an educational tool it also needs to be a place where people want to live, the university is planning to grow in an attempt to help repopulate Venice’s main islands. A project called Venezia Città Campus has been established in collaboration with city hall and Venice’s other public university, Ca’ Foscari, which will expand teaching space and student accommodation to welcome an additional 60,000 students in the next 10 years.

“We need to show ourselves to the world not just as a mythical place to visit but also as a tangible possibility for residency and work,” said Venice mayor Luigi Brugnaro at an event presenting the project in early 2023. “Venice anticipates the problems that affect the entire country and it’s important to find solutions, like we did with Mose.” By putting its students in front of such problems, and by presenting its own ways forward by contributing to projects such as Venezia Città Campus, IUAV will play a leading role in building the Venice of the future. Other cities around the world will be watching closely.

Brothers in arms

At a time when defence forces are under increased scrutiny when it comes to recruitment and deployment due to wars raging in Europe and the Middle East, it might seem peculiar that some armed services are concerned not only with their military prowess but their image too. “The war in Ukraine changed a lot,” says Markus Gut, a partner at Farner, a Zürich-based communications agency. “Some people had doubts about whether the Swiss army was strong enough or could protect us. But the Swiss armed forces had never had a brand and so we were asked to create one. It wasn’t just a matter of saying, ‘We are competent’ or ‘We are proud’; it had to be something strong that you could feel.”

On a sunny afternoon, Gut is taking Monocle on a tour of the company’s office on Loewenstrasse, where he and a small team of branding specialists, led by Farner’s consulting director Martin Fawer, have spent the past year creating an identity for the country’s famously neutral military service. The studio has developed a logo, colour palette and typeface for use on everything from uniforms and storage containers to websites and official documents. “The goal for us was to craft something unique, Swiss and timeless,” says Gut. “The corporate design of Swiss Railways is a good example of what we wanted to build,” he adds, referring to the red-and-white logo by Swiss designer Hans Hartmann, which was introduced in 1972. “It’s very Swiss.”

But why, in a country where it is compulsory for every man over the age of 18 to serve in the military, does having a strong, recognisable and attractive identity matter? “The aim is for our soldiers to recognise themselves in the brand and to carry their experiences as ambassadors [of the Swiss army] into civilian life,” says Glenn Müller Amstutz, the head of defence communications who commissioned the project. “It is also the face that our army shows other countries, which is why it was important to do it in the Swiss style,” adds Gut.

To develop an identity that spoke to soldiers, other forces around the world (which the neutral Swiss encounter during joint training operations) and civilians, the Farner team conducted a number of consultation workshops. “We worked with the army to sharpen its profile, conducting the whole process together,” says Fawer, who led a series of interviews with male and female soldiers of various ranks at the army’s communications office in Bern. “We asked them, ‘What do you think about the army? What is important about it? What is its attitude?’ This was followed by several workshops, where we showed them how other armies’ brands – like the British army and the German army – are presented.”

The results led the Farner team to pin down four key values for the Swiss army – a military that is “stolz, diszipliniert, kameradschaftlich und kompetent” (proud, disciplined, comradely and competent) – and to the design of a logo. It was a first for the Swiss army which, until that point, had lacked one and instead, as neither a government administrative unit or an institution, simply used the Swiss flag as its official mark.

“That was one of the desires of Thomas Süssli, the chief of the Swiss armed forces. He wanted to have a logo but the design had to reflect the army’s values. You can’t just tell Martin to make a nice logo,” says Gut, nodding at Fawer. “He will reply, ‘What is it for? What are the company’s values?’”

Brand new look

The newly designed core elements including logos, guidelines, advertising executions and digital application.

To give the new logo a Swissness and respond to the values of pride, discipline, camaraderie and competence, the team turned to Helvetia for inspiration – an allegorical female figure wielding a spear and a shield with the Swiss flag emblazoned on it. “Everyone in Switzerland knows Helvetia because she is on our coins,” says Gut, pointing at a one-franc piece that shows Helvetia drawn by 19th-century German artist Albert Walch. Farner used the outline of the Walch-drawn shield on the coin as the basis for the new logo. “It made sense: the shield is a symbol of defence and the message is that the army is here to protect you,” says Gut. “No other company uses the shield in their branding.”

To further differentiate the new logo – in a country where red-and-white crosses are ubiquitous across state and private brands – the team chose black, white and red as its colours. “From Swiss army knives to chocolate, many firms here use the red and white as a sign of quality,” said Gut. “The black is actually a non-colour.”

For the typography, the studio chose Helvetica, the classic typeface that was developed in 1957 by Swiss font designers Max Miedinger and Eduard Hoffmann, which it used to display the words “Swiss army” in the country’s four national languages. This rooted the visual identity even more firmly in Swiss design tradition. “From Helvetia’s shield to Helvetica typescript, it is all very Swiss,” says Gut. “It couldn’t work for another country’s army but it is perfect for Switzerland.”

It’s a reminder that branding matters – and, at a time when the threat of war can sometimes feel imminent, it is essential for armed forces to have a strong brand identity that reflects their principles and elicits confidence in the populations that they protect.

Uniform approach

Fashion trends come and go at lightning speed, but one is proving to have lasting effect on wardrobes. Workwear has gone from being associated with the working classes to being embraced by style communities and subcultures around the world, from skateboarders to British punks. It’s a category that has been a fixture on the sartorial landscape for quite some time but today it has gained newfound momentum in mainstream men’s and women’s fashion – helping to shape the way we get dressed and set a new style agenda for 2024.

In all four fashion capitals this year, houses grounded their ready-to-wear collections in styles synonymous with workwear. Celine, Ferragamo and Brunello Cucinelli opted for suede trucker jackets in their collections, while Coach offered gabardine and denim dungarees. Versace and Prada paraded utility vests, while Fendi featured leather aprons and tool belts – an homage to the elegant uniforms worn by the workers in its new leather-manufacturing facility in the Tuscan town of Capannuccia. It joins MaxMara, where creative director Ian Griffiths looked to Britain’s Land Army with his dyed drill boiler suits and chore jackets, to inspire his collection for next spring. Designers across the luxury spectrum are referencing humble workwear archetypes, while original workwear brands such as Carhartt wip and Dickies are enjoying renewed popularity.

But why the sudden appeal? For one, people are drawn to the way that workwear whispers smart-casual, says Lucie Greene, trend forecaster and founder of consultancy Light Years. “Workwear has almost become quiet luxury for the original hipsters,” she says. “As this group reaches financial maturity, it is starting to embrace the workwear aesthetic in a more refined way, looking for indulgent materials. But core design values, such as reductionism, sturdy quality and industrial cues, remain.” Pointing to new-wave workwear-inspired brands, including Alex Mill and Studio Nicholson, Greene notes that their appeal also lies in a unisex approach, creating “a modern uniform for anyone who wants elevated comfort”.

Workwear addresses our demand for increased comfort while providing a refreshing alternative to the streetwear wave of the past decade. It also shines a spotlight on the value of embracing classic design and eschewing trends. “This reflects a broader social and cultural shift in values and preferences in which people are seeking authenticity, durability and functionality in their clothing choices,” says Carolyn Mair, author of The Psychology of Fashion. Mair notes that workwear fosters a mindset that views clothing as long-term investments. “By prioritising craftsmanship and wear-forever clothing, brands and consumers are embracing a paradigm that reduces consumption, extends the lifespan of clothing and minimises waste.”

Such is the continued appeal and success of the original workwear brands in hooking new customers, luxury designers need to elevate and move the design along to offer something fresh. Labels such as Japan-based Sacai (which has recently collaborated with Carhartt WIP), Britain’s Olly Shinder and Fendi have all been helping to diversify the market, so much so that today the swing tags of workwear garments oscillate from accessible to premium. At luxury multibrand retail outfit Matches Fashion, menswear buyer Alexander Francis has bought into workwear styles from Carhartt WIP, Drake’s, RRL and Visvim, some of which are under the £100 mark (€115) and average around the contemporary price bracket.

“All these brands offer go-anywhere, do-anything products at a selection of price points,” he says. “We are seeing customers looking for styles that can work in the office and at the weekend. It’s about buying less but buying smarter – and workwear really talks to this shift in behaviour.”

While Francis doesn’t predict a return to the head-to-toe workwear dressing of the early 2010s, he points to “die-hard” workwear style icons such as Daniel Day Lewis and John Mayer “who show that a uniform approach to workwear remains a classic look”. The uniform element of workwear strikes a chord: see the rise of the Danish fashion industry or bellwether brands such as Prada using their fashion shows to celebrate uniforms associated with the care sector and workwear (the irony of a €4,000 full-length donkey jacket noted).

For Morten Thuesen and Letizia Caramia of uniform specialist Older, a Milan-based business, “uniform means longevity”. In the decade since they left their jobs at Alexander McQueen in London to explore the artistic potential in the industrial side of uniforms (their clients include the Noma Group, Tate Modern, Château Marmont and Flos), they have become experts in the space. “Uniforms have always been a fascinating aspect for fashion – it’s to do with the tailoring and understanding proportion,” says Thuesen. “Our ideology is that the uniform is democratic and that needs to be translated in the design but also the pricing, supply chain and production.” As for Lawrence Steele, a fellow Milan-based designer and creative director at Aspesi, uniforms have gone from symbols of restriction to a form of “liberation” from the daily task of getting dressed.

It’s by the same notion that workwear is again in the spotlight. “Craft used to be seen only in terms of hand-sewn garments, while manufacturing had associations with mass production and low quality,” says Greene. “New-wave workwear highlights the intersection of hand craft and old-school manufacturing, associated with true skill in small-batch production, ingenuity in mechanical machines and pride in clothing emerging from factory towns.”

It hails a new era. As Mair puts it, this chapter in fashion won’t be defined by a trend for a change but “a fundamental shift in the psychological relationship that people have with their wardrobes”.