The Forecast

Art for the people

On workdays, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, the new director and chief curator of Haus der Kulturen der Welt, cycles from his home in Neukölln to the office in Berlin’s Tiergarten park. “Every time I cycle down Karl Marx Allee, I cross different geographies,” says the Cameroon-born curator of his commute. “You can see the people and hear the languages change when you cross. This institution must belong to these people,” he says, turning his attention back to the museum he’s in charge of.

Since taking up his post in January 2023, Ndikung and the team have made huge strides to bridge the gap between the German capital’s sometimes high-minded art institutions and the tastes and desires of the 170-odd nationalities living here. Instead of just presenting art and ideas to the Berlin public, the Haus (known to Berliners as “HKW”) has created a dialogue where exhibitions, performances and events try to properly connect people with the far-flung topics it touches. “The idea was to create an institution that reflects the different kinds of people who live here,” he says in his trademark baritone.

When O Quilombismo, a 68-artist exhibition, opened in spring 2023, the mission became a little clearer and offered a taste of Ndikung’s tenure to come. At the three-day open-house extravaganza, art lovers thronged HKW, where art adorned exhibition spaces as well as corridors, the atrium and even the building’s auditorium. Despite the serious subject matter (“quilombos” are self-governed communities founded by enslaved people in Brazil) it was the sense of levity and excitement – rather than sombre soul-searching – that was inescapable. Visitors of all ages hung out in a flag-festooned outdoor pavilion where a “kids’ disco” allowed youngsters to have fun while their parents took in the art. Sculptures, flags and installations by the likes of Ghanaian art star Ibrahim Mahama dotted the grounds and added colour and vivacity to proceedings.

On the flat parts of a sweeping roof (Berliners have long referred to the oddly-shaped building as “the pregnant oyster”), food stands served Thai, Cameroonian, Nigerian and other specialities to the sounds of live bands from across Africa and beyond. Above it all, three flags flew in black, red and green stripes, each emblazoned with a letter: together they read ddr, an acronym standing for “decarbonise, decolonise, rehabilitate”: so far so serious? Perhaps, but this pointedly also stands for “Deutsche Demokratische Republik”, the name of the former East Germany. Fluttering close to the Federal German Chancellery and parliament buildings, the flags were artist Olu Oguibe’s poignant nudge to audiences to radically rethink the notion of Germany’s own divisions and all it’s been through.

The building was erected in the 1950s by the Americans, who later donated it to the West German government. In 1989 it became a cultural centre. In recent years the space attracted a cerebral set including exhibitions on the cia’s involvement in art and conferences on art-world topics such as the Anthropocene. Ndikung’s tenure, however, meant broadening that definition of art. “Berlin is one of the most unique cities in the world,” says senior curator Cosmin Costinas, who moved to Berlin from Hong Kong to work with Ndikung. “Because [the layers of migration are] so recent, the connections between people and their countries of origin are deeper and more alive.”

HKW’s agenda is in stark contrast to conventional art-historical institutions – especially the sometimes-criticised Humboldt Forum, another Berlin institution dedicated to non-European objects and art that opened in the summer of 2021. The Humboldt Forum, like many museums today, is in flux, paralysed by questions of provenance, power and some darker parts of Germany’s history. It holds the state ethnological collections, including the Benin bronzes, which Germany has begun to return to Nigeria. While the hkw has its own history, the curators and staff aren’t looking back; they’re trying to start a new chapter including renaming all the public spaces after women who worked, often invisibly, to improve lives. One of the ponds in front of the building is now named after Chilean folklorist Violeta Parra and the hkw offices are named after Senegalese women’s rights campaigner Awa Thiam, to name just two.

Other changes were internal: instead of hiring a large staff on the art world’s precarious year-by-year contracts, Ndikung – Berlin’s first non-white museum director and a biotechnologist by training – offered longer contracts and fuller benefits but to fewer team members, many of whom hail from Africa and South America. East Germany-born Henriette Gallus is deputy director, a unique position in a system that still generates star museum directors (“No one can do this alone,” she says). After a long research phase beginning when Ndikung applied for the job in 2021 (a big decision after founding and operating Savvy Contemporary, a wildly successful project space, for more than a decade), the two restructured the HKW during a five-month closure. Teams now work across artistic disciplines, their members have more agency and the opportunity to combine family and work is not just a perk but a priority.

Forthcoming events will tackle the idea of the “Global East”, including Germany’s own past. But the HKW wants to generate some intrigue, fun and curiosity rather than shutting down conversations or tying itself in knots trying to signal its own virtue. “We want the audience to understand that this is about them: about their daily life, their understanding, love, passion and tears,” says Gallus. Just two weeks after HKW reopened, O Quilombismo was already the one of the most-visited exhibition the space has hosted in the past 25 years. The visitors kept coming – many more than once – and often for hours. The opening weekend’s kids’ disco was such a success that parents asked for more; HKW now runs it twice a month. “People feel like they’re a part of it,” says Gallus. “That’s the magic of us with the audience. Without them, these would be empty halls.”

Greek revival

Every autumn the 21km stretch of beach leading northwest from Athens to the city of Elefsina hosted a set of ancient rites intriguingly dubbed the Great Mysteries of Eleusis. Initiates, sometimes thousands at a time, take part in the secretive nine-day ritual – including toasting the dead and some walking – that was once said to promise eternal happiness in the afterlife. While a visit today might not offer a ticket to a happily-ever-after place, Elefsina (formerly Eleusis) is a great example of how being nominated a European Capital of Culture can help smaller cities jostle for cultural prominence at home and abroad.

Since its ancient heyday, the hills and olive groves have been cut through by a six-lane highway dotted with petrol stations, fast-food joints, junk yards and refineries that obscure the view of the sea from the Bay of Elefsina. The road is at once one of the most sacred of antiquity – walked by Plato, Socrates and several Roman emperors – and an industrial backwater that’s still easily missed by holidaymakers and commuters shuttling back and forth to the Peloponnese.

Monocle exits the motorway on a fair Friday and finds shade in a courtyard of a disused olive-oil mill close to the waterfront. It is the setting for an exhibition called Elefsina Mon Amour: In Search of the Third Paradise. “For Athenians, Elefsina has long been terra incognita,” says curator Katerina Gregos. Soon a well-heeled crowd of locals and Athenians fill the courtyard to toast the opening. At sunset they’re whisked off by bus to a two-hour dance performance set against the rusting hull of a stranded ship. These are just two events that have happened as part of the city’s stint as a 2023 European Capital of Culture; many here hope that this will help get this city back on its feet.

This is the fourth time that Greece has hosted a European Capital of Culture, starting in Athens in 1985. The story goes that Melina Mercouri, actress-turned-minister of culture, came up with the idea while stuck at the airport with her French counterpart Jack Lang in the early 1980s. Mercouri pitched it to the European Commission and the EU obliged by footing the bill. The blockbuster first edition included a 10-hour play and shows by German choreographer Pina Bausch, Swedish director Ingmar Bergman, jazz from Miles Davis and plenty of fireworks. In the following years, successive European cities took their turn in the limelight by hosting the cultural festival.

The definition of what makes a European Cultural Capital has shifted over time. Apart from awarding the title, the EU’s support is mostly of the moral kind and funding is limited to a €1.5m Melina Mercouri Prize. Since 2000, multiple cities have been appointed each year based on formalised selection criteria (the rotation of host countries is set by the EU parliament and cities are picked through national competitions). Instead of established cultural centres such as Athens or Amsterdam, the priority has shifted to more peripheral, post-industrial cities that could use a lift: think Timisoara in Romania and Veszprém in Hungary. Even so, many were surprised when, in 2016, Elefsina was awarded the title for 2021 (postponed to 2023 due to the coronavirus pandemic). With just 20,000 inhabitants, it’s the smallest European Capital of Culture to date and, while the archaeological site at its centre is famous among classicists, even some locals were left scratching their heads at what culture would be on offer to visitors.

If you walk along Elefsina’s central thoroughfares, you’ll see some sweeping contrasts: on one side there’s the ancient Well of Demeter, where Homeric myth puts the harvest goddess mourning her lost daughter Persephone, and on the other is a gaming parlour with street-side slot machines. The top stay is the city’s sole four-star hotel and the only cultural venue before the festivities was a rickety outdoor amphitheatre. “There was no infrastructure,” says Michail Marmarinos, artistic director of Eleusis2023. “It was a huge challenge.” Marmarinos, one of Greece’s foremost contemporary playwrights, stepped in as artistic director in 2020. He secured a postponement and herded the whole organisation into action. Marmarinos’ theme became “Mysteries of Transition”, a remix of the city’s ancient claim to fame and a hope that a new procession might spur its cultural growth beyond its Capital of Culture tenure.

The transition that Elefsina is undergoing is a version of the story shared by many European Cultural Capitals: of reviving a city built and then abandoned by heavy industry. At the turn of the 19th century, Elefsina’s shore was lined with shipyards, refineries and soap and cement factories. Immigrants from all over Greece and the Balkans arrived in search of work. In the 1970s the factories spewed so much ash into the air that Elefsinians couldn’t even hang their laundry outside. The sea was more black than blue.

“This was really a scarred landscape, in many senses of the word,” says Gregos. For Elefsina Mon Amour, she invited 16 artists from nine countries to create newly commissioned pieces (a key goal of the European Capital of Culture is to put artists to work). The exhibition is spread across three dimly lit factory halls. The show’s title is a reference to Hiroshima Mon Amour, a 1959 film by Alain Resnais. “Only the difference is, the catastrophe [here] did not come from nuclear war but from industry,” says Gregos.

The mystery of Elefsina

Elefsina lies on the Thriasio plain, which grew the wheat that fed ancient Athens. At about 600 bce, the cult of Demeter started holding annual rites around harvest season, which grew to become the most important in the Greek and later Roman Empire (nobody knows exactly what they involved thanks to a death penalty-enforced antecedent of “what happens in Vegas”).

“The city offered the term mysteries – and art itself is a mystery and the goal of a European Culture Capital is transition,” says artistic director Michail Marmarinos. Each element of the festival was titled “Mystery”, followed by a number as a nod to the ancient intrigue.

Marina Gioti spent more than three years on an artwork called “Sounding the Silent World” for which she mapped the shipwrecks in the Elefsinian gulf using sonar. The resulting abstract, amber images are mesmerising and highly political: Gioti was forbidden from publishing the names of the 12 ships she found decaying on the seafloor. The bay is still strewn with abandoned ships but the clean-up of the sea started in the 2000s and now locals happily jump in for a swim.

Artistic duo Joanna Tsakalou and Manos Flessas created “Hadal Zone”, a visual opera in five acts, which leads up to the top of an outdoor amphitheatre, where visitors are serenaded while taking in Elefsina’s industrial horizon through binoculars. The vista is memorable. Just down the coast, one of the largest oil refineries in the Balkans shoots up a flame every few seconds.

As night begins to fall, Monocle returns to the Old Oil Mill. “It looks like Manhattan,” says Yorgos Skianis as he looks out over the jumble of factory buildings. Skianis, an Elefsina local, organised the Aeschylia Festival that connected visual artists with factory spaces to exhibit their work long before the Capital of Culture crowd showed up. “We showed people that Elefsina can produce more than just pollution,” he says, drawing attention to the fact that Capitals of Culture need backing after the banners and EU funds have been and gone. He tells Monocle about growing up in the city when it wasn’t possible to access the waterfront at all. “We Elefsinians used to avoid saying where we were from. There was a stigma,” he says as the venue’s DJ strikes up and the crowd begins to move in rhythm. “They are proud,” he adds, gesturing to the people and raising his voice with the crescendo of the music. “Today nobody pretends not to be from Elefsina.”

Monocle’s Small Cities Index

Tired of the bustle of the big city? With the pace of life ever increasing in our always-on global capitals, we wouldn’t be surprised if you’re enticed by the idea of moving somewhere smaller – a relaxed, easygoing environment where things can unfold more gently. Unfortunately, such a move often has its downsides, from limited business opportunities and small social circles to poorly connected airports (if there even is one).

But what if there were pockets of urban life with populations of fewer than 350,000 inhabitants that weren’t afflicted by such problems? It’s these places that we’re highlighting in the fifth annual Monocle’s Small Cities Index. Safety, proximity to nature, an economy that supports new businesses and strong creative and hospitality sectors were among the key criteria when it came to identifying our top-25 picks for 2024. The resulting selection also includes a “best for” guide, offering some inspiration for those who need a little nudge before considering a move.

Here, we sip a vermut on the seafront of an overlooked gem in northern Spain, enjoy the catch of the day in a Japanese island city and luxuriate in the lush gardens of a former imperial outpost in Brazil. You could too.

1.

Naha

Japan

Best for island life

Increasing numbers of creatives and entrepreneurs have been returning or moving to the city of Naha in recent years. Among its draws are its fusion of cultures, a warm climate and all the perks of living on a rocky outcrop.

As soon as you step out of Naha Airport, you sense that this is Japan – but not as you know it. The air is more humid, the plants more tropical. The taxi driver is likely to be sporting a floral shirt. And then there’s the vibrant, blue sea. With a population of about 320,000, Naha is the capital of Okinawa prefecture, a string of islands at the southern end of the country that almost reaches Taiwan.

Okinawa’s history is evident today in its distinctive culture that fuses Japanese elements with those of the historic Ryukyu Kingdom, which was independent until the late 19th century, as well as a sprinkling of Americana. After the Second World War the US held onto Okinawa until 1972. American brand names linger – such as Jimmy’s, which has been baking cakes here since 1956 – as does a taste for Spam. Visit a market, however, and you’ll see the fresh food that has helped to make Okinawans the longest-lived in Japan: goya gourds, winter melons, sea grapes and a selection of fish unfamiliar to cooler waters.

The pace of life in Naha is slower than on the mainland. Some start their day with a dip in the sea at Naminoue beach. With its leafy streets, concrete modernism and small restaurants, the city is a pleasure to walk – unusual in car-centric Okinawa. Tatsuya Irei, who was born here, recently moved back from Tokyo to open Wayobu Yoshi restaurant in Tsuboya, Naha’s pottery district. “I wanted to raise my family in my hometown,” he says. “Children are too constricted in big cities.” He buys fish and fresh food from markets outside Naha in Itoman and Yonabaru; on days off, his family hits the beach. “Okinawa is compact. I can hop in the car and be in Nago in the far north in an hour.”

Nami Makishi, another returnee, co-founded interiors studio Luft in Tokyo but came back to Okinawa with fellow designer Chikako Okeda. “We love the diverse mix of native Okinawans, people who have moved here from other prefectures and tourists,” she says. Multiple flights connect the city to Tokyo from morning to night and Taipei is only 90 minutes away. Tourists throng Kokusai Street and Makishi market but residents go about their business with good cheer. “The flow of time is just different here,” says Makishi.

2.

Santander

Spain

Best for architectural inspiration

Santander enjoys a wealth of contemporary architectural treasures. The Centro Botín arts centre was designed by Pritzker Architecture Prize-winner Renzo Piano and a Banco Santander-backed art gallery by David Chipperfield is in the works.

In Santander, a city of 172,000 on Spain’s northern coast, nobody is in a rush. If you’re late for a meeting, call ahead and surrender to the pace of the locals ambling along the harbour promenade. Defined by its low- and mid-rise apartment blocks stacked up a sloping peninsular, the Cantabrian capital has narrow streets on which you’ll find an assortment of cafés and restaurants. It’s the sort of enclave where the terraces are packed with customers sipping vermut at 14.00 on a Tuesday. Historically known for its fishing and shipbuilding industries, the port city has increasingly benefited from tourism and the fact that Banco Santander has its institutional headquarters here. Young start-ups and restaurateurs are tapping into the low cost of living, the city’s cultural scene and the connectivity afforded by its international airport.

“I live here because of the quality of life,” says Berta Betanzos, a retired Olympic sailor who now co-owns Tanndem, a gym near the bay. When Monocle asks why Betanzos, who grew up in Santander, decided to stay, she says that the city’s sheltered location and mild climate lends itself to endless recreational opportunities. There are more than a dozen beaches within walking distance of the city centre and the distant peaks of the Cantabrian mountains surround the bay. Architect Jacobo Gomis took advantage of this outlook in 2012 when he opened Centro de Surf, a geometric concrete building on the popular Somo beach near Santander, which has become a hub for those in need of lockers, surfing lessons or a beer. “I grew up surfing here,” he says. “Now I take my children.”

Entrepreneurs such as Carlos Zamora Gorbeña, who runs La Caseta de Bombas restaurant with his sister, Lucía, have also tapped into the outdoor lifestyle. “People are connected to nature here,” he says. “Everything is a short walk away.” One of the restaurant’s patrons, Katherine Browne, is looking out across the bay with an aperitif. “People are friendly and there’s a good work-life balance,” says Browne, who moved to Santander from Ireland 20 years ago and owns a jewellery business. “I’m happy here. I feel safe.”

3.

Petrópolis

Brazil

Best for those seeking a subtropical enclave

Many Brazilian cities are celebrated for their beachfronts, meaning that those further inland are often overlooked. Petrópolis offers the best of both worlds: it’s an easy morning excursion to Rio de Janeiro’s best beaches, so residents can return to their city’s cool climes for a breezy afternoon.

Less than a two-hour drive north of Rio de Janeiro in the mountainous Serrana region, Petrópolis was built in the 19th century as a summer resort for the Brazilian imperial family. The factors that drew Pedro II here remain its biggest attractions: a cool climate, tranquillity and proximity to the country’s second biggest city. A popular weekend getaway from the chaos of its formidable neighbour, this city of 300,000 offers closeness to nature, lively culinary and cultural scenes, and a good choice of universities. The walkable city centre mixes neoclassical architecture with an eclecticism that reveals the influence of German settlers. It’s also just a short distance from the Serra dos Orgãos national park and Rio’s international airport.

Tourism and hospitality are important to Petrópolis’s service-oriented economy but the city is also known as a centre of organic produce and beer, with many breweries. The SerraTec technology hub attracts cutting-edge talent and there’s a lab that hosts Latin America’s fastest supercomputer. Petrópolis’s creative scene is thriving too. Rio-born furniture designer Gustavo Bittencourt moved here 10 years ago for the space and skilled labour that the city offers; his workshop is now located in a hangar in an industrial neighbourhood surrounded by a verdant forest. “There are innumerable good things about Petrópolis: safety, the climate, the people, the cuisine,” he says.

Some accuse the Imperial City, as it is still known, of being stuck in the past. It is certainly hard to escape the weight of history, whether you’re sipping a coffee in the gardens of the former imperial home or people-watching under pink-flowered sapucaia trees on Freedom Square (where the enslaved used to buy their independence). But entrepreneurial Petrópolitanos returning from bigger cities or from abroad are keen to keep their city relevant. Among them is Dani Abaut, who runs a ballet studio for professional dancers and is an enthusiastic advocate for her hometown. “My main reason for coming back to Petrópolis was that I wanted to contribute to making it a better place,” she says. Luckily, these improvements are starting to show.

4.

Newcastle

Australia

This city’s 320,000 residents have the best of the Australian east coast: sandy beaches, affordable house prices, a flourishing culture and culinary scene, and close proximity to the Hunter Valley wine region. The historical port remains busy but, beyond its industrial roots, central Newcastle has been undergoing a rejuvenation. A new light-rail system was completed in 2019, connecting outer suburbs with the waterfront, and the old red-brick train station has been transformed into a covered market hosting pop-ups and events. At its heart is Darby Street, a stretch of cafés, restaurants and boutique shops. Here, young families, established residents and students with flat whites bask on sunny terraces between beach breaks.

Best for small-scale big-city living

Though it’s only a couple of hours from Sydney, laidback Newcastle has an established sense of self, with a strong cultural and business scene.

5.

Eindhoven

Netherlands

The size of this industrial city, with a population of about 250,000, belies its technical capabilities, which are among the strongest on the continent. It’s known as the Dutch Silicon Valley due to the city’s University of Technology as well as Eindhoven-founded electronics giant Philips, which have contributed to its reputation as an EU technology hub. But it’s not all semiconductors and lightbulbs; Eindhoven also has a strong design focus thanks to the Dutch Design Academy, established in 1947, which is one of the world’s leading design schools. The annual Dutch Design Week also takes place here, while rail links to Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Antwerp are fast and frequent.

Best for design and technology

In a country with one of the world’s most open economies, Eindhoven is an ideal spot for innovation and development in fields from agriculture to architecture.

6.

Basel

Switzerland

Switzerland’s oldest university town has always had a youthful energy. The city of 190,000 is the country’s cultural capital, with more than 40 museums and galleries – most notably the Kunstmuseum, containing the world’s oldest public art collection. It’s also the home of Art Basel, the world’s leading contemporary art fair, established to give smaller galleries global prominence. More recently, life sciences have become a major industry in a city considered to be a pharmaceutical hub and a beacon of technology, attracting more than half of Switzerland’s employees in the field. This well-connected town on the Rhine has been sweeping up students, entrepreneurs and creatives in its fast-paced current for centuries.

Best for continental connections

In a city bordering three countries, residents can earn Swiss salaries with German expenses and French cultural life. What’s not to love?

7.

Victoria

Canada

Established as a trading post, Victoria (population: 92,000) is buzzing with young businesses, including award-winning furniture firm Part & Whole, established in 2018, and Shuck Taylor’s (stop by for the best oysters in town), which is shaking up the culinary scene. For its remote location, Victoria is surprisingly well-connected, with an international airport and frequent ferry trips to Vancouver (90 minutes) and Seattle (three hours). The city has a thriving media scene, with more than 10 radio stations, and magazines such as The Narwhal and Hakai. But key to Victoria’s appeal are the mountains, lakes and coastline surrounding it. You will hear of residents going skiing one day and swimming the next.

Best for going on- and off-grid

Like neighbouring Seattle and Vancouver, Victoria is a comfortable place to set up shop on the Pacific coast. But here you can be closer to nature without losing connectivity.

8.

Keelung City

Taiwan

There’s plenty to do – and eat – in Taiwan’s port city of Keelung, despite its small size. A 50-minute train ride from central Taipei, the coastal hub of about 350,000 benefits from close proximity to the country’s capital, as well as Taiwan’s strong business relationships with surrounding countries. Several easy day hikes start from Keelung, providing a great warm-up for a late feast – the city claims Taiwan’s best night market for seafood, with specialities such as swordfish, deep-fried crab and Taiwanese-style tempura. Keelung also has strong cultural significance – fortifications date from the 17th to the 20th century – while the mountain resort town of Jiufen is a short distance away.

Best for hiking and biking

Keelung’s surrounding landscape offers an abundance of walking and cycling trails along its rugged coast and through the surrounding mountains.

9.

Dunedin

New Zealand

Dunedin has a gothic vibe, to which the architecture (Edwardian) and fashion (with a penchant for black) contribute. But the city of 130,000 is also a beach lover’s paradise where residents are almost blasé about sharing their shores with seals and penguins. Despite this, music and fashion are what the city has become known for. Aspiring designers flock to Otago Polytechnic’s fashion school, while the established descend on its fashion week, with many creatives basing themselves here as a result. Dunedin’s prices are competitive, with affordable homes that enjoy sea views. The city is walkable but hilly. Residents defend their steep gradients as “good exercise”.

Best for setting up a remote outpost

Well connected to the rest of New Zealand but hidden from much of the world, Dunedin’s fashion and music scenes can be adventurous without fear of outside judgement.

10.

Toulon

France

Between the Med and the mountains, Toulon offers a change of pace with a dash of French flair. Until recently, the city’s reputation was that of a naval base overrun by drunken sailors but today the friendly port city boasts markets brimming with fresh produce, fashionable restaurants and fascinating culture. Annual events, including Design Parade Toulon – organised by the Villa Noailles in nearby Hyères – attract crowds of creatives from Paris and nearby Marseille. The city’s accessibility is also set to increase: more high-speed trains running between Paris and Toulon are being introduced in 2024.

Best for life by the Med

A mild climate facilitates morning dips in the sea, while cyclists and hikers can head into the surrounding mountains. The city’s economy is varied: fishing, winemaking and manufacturing of naval and aeronautical equipment all take place here.

11.

Patras

Greece

The port city of Patras might be one of Greece’s most densely built but it has found ways to inject stretches of open space into its bustling urban core, connecting residents to their seafront. New civic additions to this city of 220,000 include the pedestrianisation of main roads, the new North Park (opening along a stretch of seafront) and the renovation of industrial spaces. An abundance of good food and wine retailers makes it hard to leave the city but day trips are a thing of ease, with the historic towns of Nafpaktos, Mesolongi and ancient Olympia all nearby. Greece’s unsung Kalavrita ski centre is a short drive away too and ferries connect residents to the Ionian islands and Italy.

Best for budding winemakers

Patras has a long history of wine production. Nearby 19th-century castle-cum-winery Achaia Clauss is famous for sweet mavrodaphne.

12.

Salzburg

Austria

At the foot of the Alps, on the border with Germany, Salzburg isn’t lacking in charm thanks to its strong cultural pedigree and ready access to hiking and skiing. With a population of 150,000, it’s Austria’s fourth-largest city, yet remains cosy and walkable. Medical technology is big business here, with more than 60 companies combining for a €1bn annual turnover. The city is divided by the Salzach river, which flows gently through the centre – a pretty backdrop to Salzburg’s 50 galleries, numerous theatres, elegant historical buildings (such as the Mirabell Palace and Gardens) and smart cafés. And if the small city starts to feel too cosseting, Munich and Vienna are both only a short train ride away.

Best for an outsized cultural scene

Mozart’s birthplace hosts the annual Salzburg Festival, which dates back to 1920 and is still one of the world’s key events for opera, music and drama.

13.

Helsingør

Denmark

This Danish city of 63,000, famous for being home to Hamlet’s castle, offers more than a seaside setting for a Shakespearean drama. A 45-minute train ride from central Copenhagen, Helsingør has the charm of an 800-year-old medieval town while being an attractive and dynamic place to live. Residents can access a wealth of cultural destinations, from Bjarke Ingels’ maritime museum to Jørn Utzon-designed landmarks and kilometres of pristine sandy beaches. There are also efficient transport links, with regular train services to Copenhagen Airport, and neighbouring Sweden is only a short ferry ride away. Setting up shop here is a breeze too, thanks to Denmark’s business-friendly environment.

Best for cabin life

Urbanites like to spend weekends on the picturesque coast here, tucked away in wooden cabins. Helsingør’s outskirts are perfect for such dwellings.

14.

Girona

Spain

Girona’s natural landscapes and proximity to Barcelona have long attracted cyclists looking to ride along the Costa Brava. But in recent years this city of 100,000 has attracted creatives and entrepreneurial types too, with many staying for the long-haul. From independent bookshops to cafés and ceramics studios, Girona has a wealth of fresh businesses, many of which are run by newcomers. It’s an offering strengthened by a bustling food scene, which includes the likes of recently opened Restaurante Normal and the Cafè Royal. The appeal, aside from a quieter pace of life, also lies in the host of international connections from the city’s airport, meaning that Europe’s main metropolises are never far away.

Best for art enthusiasts

Girona’s seven major museums offer an ever-evolving mix of art, from antiquity to the contemporary.

15.

Coimbra

Portugal

Evenings in Coimbra, a city of 150,000, are often long and languid. And while the city’s sunny climate can occasionally be tempered by rainfall, that won’t stop residents gathering outside year-round to enjoy the beauty of its cobblestone streets and Moorish architecture over an alfresco drink. Coimbra is home to Portugal’s oldest university, the country’s second-largest library and the famed Machado de Castro National Museum. There’s a range of industries established here too, from pottery and textiles to paper production. Easy transport links to Lisbon and Porto have made Coimbra an increasingly popular location for start-ups in emerging industries such as energy and healthtech.

Best for aspiring writers

Dubbed “the city of students”, Coimbra feels like Porto’s bookish younger cousin. Its many museums and bookshops make up a vibrant patchwork of cultural organisations.

16.

Lugano

Switzerland

Nature lovers will find their calm in this city of more than 60,000, the largest in Switzerland’s Italian-speaking Ticino region. From snowy Alpine peaks to clear tranquil waters, Lugano’s surrounding scenery is all natural beauty, while the city’s proximity to the Italian border lends it a Swiss-Mediterranean flavour. Exhibition and event space Lugano Arte e Cultura houses the prestigious Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, while fashion enthusiasts can enjoy the Bally Foundation’s newly minted headquarters. Lugano’s biggest pull, however, is its namesake lake, which winds along the Swiss-Italian border, attracting a well-heeled clientele to its glamorous boutiques and hotels – only natural, given that Italy’s fashion capital, Milan, is a mere hour away.

Best for swimming and snow

Due to Swiss efficiency, Italian energy and proximity to lakes and mountains, Lugano offers year-round outdoor fun.

17.

Brescia

Italy

Located in Italy’s productive northwest, this city might have made a name for itself in metallurgy but it shows much more than just manufacturing chops these days. With a population just shy of 200,000, Brescia is less than an hour away from Milan and well connected to Verona and Bologna, as well as the Alps and Dolomites. Though other Italian cities get more press for their looks, Brescia has a stunning (and historic) centre that includes the eighth-century San Salvatore-Santa Giulia Monastery. It also has a rich creative scene, highlighted by being named an Italian capital of culture in 2023, along with nearby Bergamo. And did we mention that it’s near Lake Garda and the Franciacorta wine country?

Best for fine food

In an area that served as European Region of Gastronomy in 2017, Brescia is the main source of Italian caviar and franciacorta wine.

18.

Augsburg

Germany

This Bavarian jewel can trace its roots back to Roman times. Its modern industries range from fuselage assembly to car production and logistics, meaning that gdp in Augsburg is comfortably above the national average. As well as having a decent university and property prices below the rest of the region, the city of 300,000 is a beautiful place to wander thanks to the almost constant presence of water, from canals to fountains, all thanks to an ingenious, Unesco-recognised system that dates back to the 14th century. Augsburg’s location in the south of Germany grants it decent summers and proper winters, with easy connections, should they be needed, to nearby Austria, and Italy beyond.

Best for proximity to the big smoke

Augsburg is only half an hour from the Bavarian capital, Munich. Despite its closeness, Augsburg hasn’t become swallowed by its big brother. Rich in history, the city has its own identity.

19.

Luxembourg City

Luxembourg

Home to EU institutions and a thriving banking industry, Luxembourg City is a European capital in the guise of a liveable small town. For its 133,000 inhabitants, that’s a pretty good deal. Their home offers all the business opportunities, transport links and entertainment of big cities without excessive concrete or crowds. More than 20 per cent of the city’s surface is made up of forests. Biking and walking are encouraged; Luxembourg is investing in cycle lanes and has made all public transport free to ease congestion. Add to this the fact that it’s safe, has a multilingual population and is packed with museums and the reasons for setting up a home here are many.

Best for a European business hub

To diversify its economy, the local government launched Luxembourg City Incubator, which provides generous grants for start-ups.

20 – 25

Honourable mentions:

Six more small cities offering plenty of good reasons to put down roots.

20.

Santa Cruz, USA: This coastal city of 60,000 has a pleasant climate, vibrant beach culture, charming Victorian architecture and a dynamic downtown. San Francisco is only an hour’s drive to the north, while nearby Santa Cruz Mountains and Santa Clara Valley are teeming with wineries.

21.

Pula, Croatia: The tripartite identity of Istria, which sits across Croatia, Slovenia and Italy, is keenly felt in its capital, Pula (population: 60,000). It has a robust winemaking tradition, and a recent EU investment into a major business centre means the city’s entrepreneurial spirit is ripe.

22.

Charleston, USA: The South Carolina city has long drawn tourists to its food scene and historic pastel buildings on the waterfront. But now the city of 150,000 is enticing people to stay for good, lured by a temperate climate, breezy lifestyle and young, energetic community.

23.

Essaouira, Morocco: Perched on the Atlantic, this charming Moroccan enclave of 70,000 has always attracted a bohemian crowd. Relaxed and friendly, Essaouira’s heart is its ancient medina and the town is studded with art galleries and intriguing souks.

24.

Krosno, Poland: This city of 50,000’s strong cultural heritage has earned it the nickname “little Kraków”. Famous for its historic glassworks, a dozen smaller plants and workshops make it ideal for anyone looking to establish their own artisanal brand.

25.

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico: From its colourful colonial-era façades to the eclectic characters who live and work here, this city of 175,000 vibrates with beauty, art and intrigue. It is now attracting an international crowd looking for a place to set up creative ventures at affordable prices.

Outward shift

It’s morning in Ho Chi Minh City and motorcycles swarm the roads as office workers fill the pavements, drinking hot coffee in the sweltering heat. Amid the everyday mayhem, the first sign that something new is afoot appears in fetching cyan blue. In early 2023 a fleet of electric cabs owned by Vinfast arrived in the country’s commercial centre. For the owner of the Vietnamese automaker, starting a taxi company was a shortcut to getting these vehicles on the road in a country that has historically had low levels of car ownership.

Vietnam’s communist government opened the nation to private enterprise in the late 1980s and, after several false dawns, a middle class is at last emerging. Ho Chi Minh City is the southern gateway to this rapidly growing country of about 100 million people: skyscrapers are rising above the shophouses; two-bedroom flats are selling at New York-style prices and Starbucks has established a presence throughout the city. Michelin recently handed out its first stars to restaurants here and the French, who inspired bánh mì baguettes in the colonial era, continue to influence food retail. Though business has been bumpier than expected in the past year, one of Southeast Asia’s most enterprising cities is poised for a bumper 2024 and beyond.

Australian entrepreneur Darren Chew has had a front-row seat to Ho Chi Minh City’s transformation. Chew, who originally landed here as a tourist on his way to Europe, co-founded furniture business District Eight in 2010. “When we started out, there wasn’t a very big local market,” he says, sitting on a couch inside his company’s maiden showroom. The downtown shop opened in 2022 as a pop-up; a second, larger showroom, studio and event space will open soon. “We are leaning into the Vietnam thing a little more,” adds Chew, who oversaw District Eight’s debut at Salone del Mobile in 2023.

The business is named after the location of its original factory (Ho Chi Minh City is divided into 24 mostly numbered districts). That first building was turned into a school by the local government; the company’s second factory became a residential development. Chew must now drive for an hour to a third site in neighbouring Long An province. The journey takes him past a giant Taiwanese-owned factory that produces footwear for Nike and Adidas. Ho Chi Minh City’s largest employer, Pouyen, has laid off thousands of staff this year in response to sluggish international demand. Chew, meanwhile, has been busy adding space to meet a backlog of US orders. Once complete, District Eight’s third factory will enable the company to double its turnover by the end of 2024.

“Vietnam is a well-established manufacturing hub but the products are usually only made here, not designed here,” says Chew, who wants private-label furniture to generate half of his company’s revenue. During Monocle’s visit, Chinese furniture distributors who saw District Eight at Salone del Mobile and are interested in opening a Shanghai showroom are in Long An. This direction of travel from Vietnam to China – particularly at a time when the business news is full of stories about low-cost manufacturing moving the other way – suggests that Vietnam can be more than a substitute supply chain or a source of cheap labour. Indeed, the country is expected to become a top-10 economy by the end of the decade. Indochina Capital made its name building Vietnam’s top luxury resorts. These days the property investor, which is backed by Japanese construction giant Kajima, is developing two businesses: a hotel brand targeting 70 million domestic travellers and modern factories for European manufacturers with sustainability mandates. “Vietnam needs to define itself,” says Michael Piro, the firm’s coo and co-founder and CEO of Wink Hotels. “Ho Chi Minh City is at an inflection point, somewhere between frontier and big city.”

Foreign capital and talent has played a pivotal role in building the new Vietnam. Overseas Vietnamese are also returning to their parents’ homeland, bringing international standards, as well as an eye for design and creature comforts, from pizza to professional sports. But the need to import talent from abroad is declining across industries as a well-educated and hungry domestic workforce rises to the top.

Seoul focus

Washington might be hugging Hanoi tightly right now but it’s Seoul that is spending the most time and money in Vietnam. South Korea is the country’s biggest foreign investor and its financial commitments go well beyond Samsung’s smartphone factories, taking in sectors from insurance and mobility to pharmaceuticals and defence. Hyundai is matching Toyota here, while Shinhan Bank has replaced hsbc as the largest foreign high-street lender.

Seoul views Vietnam as a big market without the political baggage of China or Japan and it also shares certain cultural ties and customs with the country. South Korean tourists outnumber arrivals from anywhere else and can reliably be spotted heaving golf clubs through the airport, tacking 18 holes onto a business trip. According to private equity bosses in Ho Chi Minh City, most major South Korean companies have a Vietnam strategy; managers are under pressure to find investments and they tend to have a higher risk tolerance than their Japanese counterparts. Seoul also has hi-tech jobs that the Hanoi government is keen to attract.

In September, Joe Biden visited Vietnam and threw his support behind the development of a domestic semiconductor industry. Within weeks, South Korean chip manufacturer Hana Micron announced a $1bn (€950m) investment. But the Vietnamese consumer can be difficult to crack. South Korean food-delivery app Baemin seemed to do everything right when it entered the market, hiring the creative agency Rice Studios to localise its platform. But the company is now winding down its delivery business and pivoting to skincare and make-up. If Baemin’s Lazy Bee beauty products prove a hit, they could spare some blushes back in South Korea.

“Many Vietnamese who have studied in other countries are coming home,” says Chris Freund, founder of Mekong Capital, from his office in District One, where the company mostly employs local staff. Freund was an early private equity investor in Vietnam. His firm started out in low-cost manufacturing for export, before it switched to the consumer segment and struck gold with an electronics retailer. Its latest fund is betting on consumer finance and a biotechnology start-up founded by Vietnamese scientists with international degrees. “The market opportunity is great and people here are very open to foreign investment,” he says, looking out at the half-completed towers that make up the city’s skyline.

Southeast Asia’s largest steelworks is a two-hour drive east of downtown Ho Chi Minh City, close to Phu My’s deep-water river port. Inside vast factory buildings, coiled sheets of Hoa Sen’s prime hot-dipped galvanised steel await shipment to Antwerp and Leixões in Portugal. Factory bosses expect to be operating at close to capacity by April 2024, a year after production hit bottom. Vietnam’s economy came roaring out of the coronavirus restrictions in 2022, posting 8 per cent growth, before stumbling this year as a result of the global downturn and a domestic political scandal.

“It’s a bump in the road,” says Tammy Le, deputy chair of Hoa Sen Investments, during a tour. Le’s father founded Hoa Sen in 2001. The publicly listed steel company recently ventured into home improvement, opening more than 100 shops selling toilets and tiles. “There’s so much happening here,” says Le, who was educated in the US and returned home not long after Vietnam’s first McDonald’s opened in 2014. The 28-year-old joined her father earlier this year to lead the company’s diversification into various industries, including healthcare, student accommodation and entertainment. “Vietnam is the new land of opportunity,” she says, echoing the type of boundless optimism that is apparent on the ground but is rarely reflected in the international business headlines.

Export volumes might go up and down from one quarter to the next but few business leaders here appear to be basing their long-term decisions on factors such as the number of smartphone units leaving Samsung’s factory outside the capital, Hanoi. Foreign direct investment into Vietnam has continued to climb throughout the downturn and chambers of commerce are having to hire more staff to handle enquiries from their home markets, bolstered by the geopolitical trade winds blowing manufacturing away from China.

Thai company Central employs about 15,000 people in Vietnam, where it is the leader in hypermarkets. Olivier Langlet joined the company as a country CEO from German multinational retail corporation Metro at the height of the pandemic. “We want to double our number of malls to a minimum of 600,” he says, as he outlines plans to invest $1.45bn (€1.3bn) over the next four years. As he shows Monocle around one of Central’s Go! hypermarkets, he speaks excitedly about the market penetration of modern shops – in Vietnam, it is barely into double digits, which is very low compared to, say, Thailand. “We have a very nice road ahead of us to develop the business and our footprint here,” he says.

Central is considered a successful case study but making Vietnam profitable has required flexibility and patience. Langlet’s business outlook for the rest of this decade is very different to how things were when the Thais arrived in 2012 with department stores and franchised fashion brands. Most of the fashion shops have closed and there are now only two department stores. “We might come back to fashion in a couple of years,” he says.

Many businesses mistimed their market entry – and not just foreigners. Tran Thi Hoai Anh has been a trailblazer for European fashion retail in Vietnam. Starting in 2007, she opened a string of monobrand shops for the likes of Chloé, Loewe and Balenciaga, later replacing them with a multibrand shops and concept store Runway, which continues to grow. “It was too early for lesser-known labels that weren’t at the level of Gucci, Dior, Hermès or Louis Vuitton,” she says. These days, there is plenty of money in Ho Chi Minh City and the lure of Vietnam is likely to increase next year when various free-trade deals come into effect, making it easier for overseas brands to open retail outlets.

The most striking examples of Ho Chi Minh City’s economic rise can be found in property. Englishman Philip Cluer is the coo of developer Refico. He calls the current market “commercially buoyant” and for good reason. Floorspace at The Nexus, a Refico-developed office tower that is expected to open in District One in 2024, has been snapped up by a range of blue-chip foreign businesses that are clearly willing to pay Hong Kong-style rents for a prime spot in what is still a developing country. The residential sector is similarly frothy. The River is Refico’s recently completed residential tower in Thu Thiem, a greenfield area of District Two on the other side of the Saigon River. Only a few apartments remain on the market, despite a two-bed property costing about $500,000 (€475,000). The address is proving popular with South Korean and Japanese tenants, who receive a furnished apartment, fantastic views and use of an outdoor 50-metre pool for an average of $1,700 (€1,610) a month.

Thu Thiem is being marketed as Vietnam’s answer to Shanghai’s Pudong, the former rice field that was transformed into a vertiginous financial district opposite the Bund waterfront area. There’s certainly some geographic merit to this sales pitch, along with the towering ambition to back it up. A 333-metre-high Ole Scheeren skyscraper that will be Ho Chi Minh City’s tallest building is among the projects on the drawing board. That should excite anyone who has been to Shanghai.

The comparisons to China are apt in more ways than one. At the end of 2022 a Beijing-style anti-corruption drive took down one of the southern city’s most prominent property tycoons. Debt markets froze and private property firms scrambled to shore up their finances, mothballing major developments and offloading assets. Since then, jittery officials have been too nervous to grant new approvals. The extent of the fallout took everyone by surprise, hitting adjacent industries, from mattress sellers to supermarkets. Nor were international firms spared. The Mandarin Oriental Saigon was forced to put on hold plans to open at a prime address owned by the tycoon, who is still languishing in jail.

People speak about the scandal in hushed tones, strictly off the record. One common takeaway is the importance of finding a trustworthy local partner. Ultimately, no company should invest in Vietnam believing that Hanoi is fundamentally very different from Beijing, nor should they see Vietnam as a bastion of democracy, free speech or human rights. The one-party system and five-year plans deliver the same pros and cons: stability and predictability but also opaque decision-making, corruption and lack of accountability. Hanoi’s approach to the coronavirus pandemic was straight out of Shanghai’s playbook: workers lived in their factories for months, supermarkets were shuttered and the army delivered groceries. With the poor health of Vietnam’s most powerful leader a matter of public record, another major political earthquake is expected.

The effect of placing Ho Chi Minh City on ice for a year has been to create an even bigger property-development pipeline. One executive referred to 2023 as the year of paperwork, implying that when the political frost eventually thaws, companies will be ready to get going.

Some cranes and construction vehicles are already moving on the skyline but the biggest ribbon-cutting will arguably happen underground. A Japanese-funded metro is finally ready to begin operating, six years behind schedule. Though one line won’t change the daily commute for everyone, the new public transport infrastructure is a milestone. Shanghai reached this point in the 1990s and Bangkok followed at the end of that decade.

In this respect, Vietnam’s largest city is trailing behind its peers by at least 20 years. “What Thailand has now, Vietnam will need: the basics of any developed country,” says Hoa Sen’s Tammy Le. According to the World Bank and imf, the country’s economy will grow by about 5 or 6 per cent a year in the near term but those numbers are likely to be revised up as Ho Chi Minh City gets back to business. The next decade will bring more luxury apartments and modern shopping centres, as well as a prestigious design school, arenas and a proper conference centre. The longest highway in southern Vietnam will open and a huge international airport will replace the poky Tan Son Nhat – a frequent source of frustration for arrivals, who have to endure its tiresome queues. All of that construction should mean bigger commercial opportunities, a far better lifestyle and plenty more mayhem.

Second wind

If it takes a long time to turn a cargo ship around, try getting the entire shipping industry to change course – to a cleaner future. Having spent 200 years burning the dirtiest combustibles, some ship owners are discovering that the most promising technology for their industry is one abandoned years ago: the abundant, free fuel called wind. That’s why cargo decks are sprouting all manner of breeze catchers, each an ungainly prototype, competing to see which is best at augmenting grubby engine power with wind-assisted propulsion.

While these eye-catching experiments make headlines and win investment, a smaller fleet of wind-powered pioneers is sometimes overlooked. These heritage wooden schooners and newly designed sailing ships have formed a loose global alliance that’s attracting venture capital and enjoying a told-you-so moment. The maritime industry has agreed to quit carbon by 2050 but this vintage fleet is proving that, for some cargo, emissions-free shipping is available now. It might seem that the giant cargo carriers revisiting sail power and their tiny brethren who never deserted tides and trade winds sit in opposite camps. But differences aside, their combined efforts are shaking up an industry that has long been resistant to change.

It took the hottest summer in history for the UN’s International Maritime Organization (IMO) to finally commit to quitting carbon “by or around 2050”. While the finish line remains maddeningly vague, the starting gun has fired. Few sounds are sweeter to John Cooper, veteran of both McLaren Formula 1 and the Americas Cup. Now ceo of maritime innovator bar Technologies, he’s confident that ocean carriers will be transformed by sail power. Or at least, by the sail his team is designing: Windwings.

These giant steel and glass-composite contraptions can be raised to provide propulsion, lowered in a storm and manoeuvred according to the direction of the wind. The Pyxis Ocean, a bulk carrier, was the first ship retrofitted with this new technology. Owned by Mitsubishi Corporation and chartered by agricultural powerhouse Cargill, the Pyxis Ocean emerged from its dry dock in Shanghai with two huge Windwings lashed to its deck. Though they might not be pretty, these sails do look like they mean business.

We catch up with Cooper during his early morning drive to bar’s Portsmouth HQ. He’s cautious of making too many promises about Windwings’ performance. Don’t expect headlines, he says, like: “Technology provider stuns the world with their own figures.” What he does claim, however, is that his sails “have substantially more thrust than anybody out there”.

The Pyxis Ocean has already completed its first voyages – from China to Singapore, then on to Brazil and Poland – with Cooper commissioning independent experts to publicly report on its emission reductions. “No other wind-propulsion company has ever done that,” he says. “And I’ll tell you why: because they’re not making the savings that they claim. We will be dominant in this market.”

But market domination won’t come without a fight. Along with competing rigid-wing designs entering the fray, a dizzying variety of novel wind-propulsion ideas are taking shape. While cleaner fuels will also contribute to greener sailing, the surest way to reach the IMO target – and minimise looming carbon taxes – is to find the best wind solution. As a result, a parade of varied sails is dotting the horizon.

Tyre-maker Michelin is developing – what else? – inflatable sails. A couple of its Wing Sail Mobility models already help to propel the 12,000-tonne carrier MN Pelican between the UK and Spain. Modelled after aircraft wings, the retractable sails allow for navigation in ports and under bridges, and are in sea trials to assess savings. Not to be outdone, French designer Airseas looked to kite surfing for inspiration. It wants to help pull cargo ships by using flying sails, which would be attached with cables to the bow. Transatlantic tests are under way.

Meanwhile, Norway’s Hurtigruten is designing an eco cruise ship. Sketches show a classic floating hotel: bulging prow, gleaming decks and three massive smokestacks amidships. But instead of smoke pouring from the chimneys, giant sails pop out, covered in solar panels.

Whichever design wins out, the reward might be substantial. Out of about 60,000 carriers worldwide, few are currently using wind-assisted propulsion. But according to non-profit International Windship Association, that number could skyrocket to one in every six ships by this decade’s end. Yet even if this very optimistic forecast is achieved, it will still be a far cry from – and 20 long years until – the IMO’s emissions target is met. This is where the smaller wooden ships are making a mark as successful examples of zero-carbon mobility that the mainstream industry has pledged to meet.

The same week that the Pyxis Ocean set off for Europe, another sail-powered pioneer, the Tres Hombres, docked in Copenhagen. The ship’s arrival stopped traffic as, one after another, the city’s famous bridges opened to let it pass. Like the Pyxis, this ship is a remarkable sight, having crossed the Atlantic on a breeze, laden with food bound for Europe. But that’s where the similarities end. While the huge Pyxis is cautiously attempting its first deliveries under sail, the smaller Tres Hombres has completed hundreds. And though bar’s experimental wings do reduce fuel use, Tres Hombres makes the 9,000km trip without a fuel tank. After all, it’s an 80-year-old wooden boat carrying cargo the traditional way: by wind alone.

The Tres Hombres is not the only boat demonstrating how solutions from an earlier maritime age can benefit our present one. From schooner Apollonia navigating the Hudson River in New York to Sail Cargo London plying the Thames, and from France to Fiji, a growing number of entrepreneurs are putting sail heritage back to work.

It’s a rich history for Netherlands-based Fairtransport. Now in its 17th year, the company is profitable and expanding at pace. “At the beginning, we were laughed at,” says CEO Sabine Fox. “Now everyone is trying to copy us.” And it’s easy to see why. With demand increasing for climate-friendly ways to convey cargo and passengers, Fairtransport has seen its fortunes rise, even during the pandemic, various global conflicts and other ill winds. Though Fox grew up near the sea, she never expected to make it her future, training instead for a career in law. By chance, her first job was at Rostock’s Hanse Sail maritime festival. She hasn’t looked back since. At another harbour fair, she picked up a flyer from three friends – the “tres hombres” of their flagship’s name – seeking partners to find a ship and revive sailed cargo.

The boat that they found was a wrecked Second World War-era German minesweeper, destined for the scrap heap. Instead, they gave it a new lease of life as a champion of zero-carbon trade. Starting with just one vessel, Fairtransport is now a shipping agent for three more. Imports include organic cocoa, coffee, rum and other delicacies from the Americas. With a crew of 15, Tres Hombres also transports salt from France, olive oil from Portugal, honey from Spain and wine from all three. “Our customers have grown with us,” says Fox, mentioning several, such as Switzerland’s Atinkana Kaffee and Chocolatemakers from the Netherlands. “As they get bigger, we’re able to put more cargo on more ships, including new ones we’re developing.”

Asked about the new vessels and clients, Sabine demurs. “I am a little hesitant to name them because so many new shippers want our customers,” she says. “Sail cargo is definitely growing. There’s enough for everybody if we’re not all importing the same goods to the same people.” However, she is able to reveal that Fairtransport is expanding into Sweden and increasing deliveries to Denmark.

And it’s here in Copenhagen that wine merchants Rosforth & Rosforth welcomed the Tres Hombres for its third visit this year. The ship docked just past Knippelsbro bridge, which is in the heart of the Danish capital. As masts creaked and canvas stirred, the snug brigantine was thronged by locals, snapping selfies with this vision from their city’s past. Some passers-by even volunteered to help unload its 20,000 bottles of Loire Valley vintages. The boxes were then stacked on freight bicycles, which ferried them off to the city’s restaurants.

As customer demand grows, the company is helping to fill the holds of similar ships in France and Germany. Those boats are also busy with their own clients. As word spreads about truly climate-friendly transport, all sorts of requests flow in. One is from artist Olafur Eliasson’s studio in Berlin, reserving space for artwork bound for Manhattan.

While these green journeys need no fuel, they do require plenty of elbow grease. To provide it, the ships welcome passengers who pay for the privilege of being trainees and stevedores while travelling the world carbon-free. Some of these paying guests find ship life so appealing that they stay on as paid crew, with one even becoming captain. Those who sail the Tres Hombres all the way to Martinique might end up doing the frog kick, swimming with barrels of rum from tropical beaches to the side of the ship. These long winter journeys are so popular, berths sell out more than a year in advance.

For those who might prefer getting their Caribbean liquor faster, Fox suggests a visit to the German Rum Festival. At this annual Berlin conclave, the world’s finest spirits are blind-tested by experts. “There has been no year we entered when Tres Hombres rum did not win a medal,” says Fox. “Last time, it was a gold and two bronzes.” The secret? Months spent under sail. Deep in the holds of traditional ships, rum inside wooden barrels gently moves with the waves, deepening, maturing and interacting with tannins in the oak staves.

These vintage rum runners might soon be joined by a modern steel incarnation of the classic clipper ship, launched by France’s TransOceanic Wind Transport (TOWT). “What we’re creating here is a new generation of 21st-century vessels, inspired by the heritage of sail propulsion,” says ceo Guillaume Le Grand.

Seeing the advantages of both a zero-carbon fleet and mainstream carriers, towt hopes to create a niche somewhere in between. “We’re cherry-picking technologies from all the sectors: fishing, regatta, cargo,” says Le Grand. “Our boats, which are 90 per cent sail-powered, are using carbon masts and will be the sons and daughters of the old ships.”

Anemos – which is Greek for “wind” – will be the first TOWT ship, one of two set to launch in 2024. Aiming for a maiden voyage in April, Anemos is designed to have more freight capacity and passenger berths than the Tres Hombres, but only half the crew. towt also hopes for shorter crossing times thanks to mechanised sails. “We’ve got tremendous commercial traction at the moment,” says Le Grand, pointing to their ability to negotiate long-term contracts. “We’re telling customers that one hop across the Atlantic for greenwashing PR is not what we do. If you want to load your cargo on board, you’ll have to sign a contract that commits you to several crossings.” So far, TOWT has firm cargo commitments from wine and spirits seller Pernod Ricard and other leading French brands.

This is still a period of experimentation, development and investment for both sectors: the sail-only fleet and its giant cargo cousins. And there are opportunities for co-operation. One example is the crucial last mile of carbon-free delivery. Many mega-freighters can only squeeze into huge container terminals. Agile smaller craft can meet them dockside, cross-load cargo, then navigate it to downtown Hamburg, Amsterdam, London and countless other harbours.

Wind-assisted propulsion might also lead these different fleets to sail the same routes. Standard cargo ships, using engine power alone, could sometimes ignore breezes when mapping a journey. But as they adopt hi-tech sails to reduce emissions, that calculus will change. According to Cooper, it might even prove economical for sail-assisted carriers to stop going back and forth across the Atlantic. Instead, it could be smarter to sail continuously around the globe, following the trade winds. In that scenario, the heritage cargo fleet – along with racing teams and other open-ocean mariners – will have valuable experience to share about optimising routes and logistics for wind. So like sharks and remora fish, the massive cargo carriers and small sailing vessels might find ways to assist each other as maritime commerce goes green.

But what has been most important to both fleets is that vintage ships are proving themselves powerful ambassadors for wind-powered transport. They’re building global awareness and a loyal customer base, which is willing to pay the sometimes higher cost of transitioning to clean ocean shipping.

Whether the two sectors choose to compete, co-operate or ignore each other, one thing is clearly on the horizon: more sails. Lots of them – steel ones bolted to giant carriers and canvas flapping on ships such as the Tres Hombres, returning the richness of slow-sailed coffee, cocoa and rum to Denmark’s capital.

But for Danes, the most exciting taste these ships are delivering might be something else. By reviving dockside flavours and accents, clamour and commerce, visitors such as the Tres Hombres are also bringing back the original meaning of the name Copenhagen: Merchants’ Harbour.

Ways of seeing

Scott Young on …

How geopolitics will shape the manner in which AI will change the job market. Amid the uncertainty, there are things that we know and even some reasons to be cautiously optimistic.

Technological prognostications often fall prey to what’s called “Amara’s Law”, a phenomenon suggesting that we tend to overestimate a technology’s near-term impact while grossly underestimating its effect over the long run. Artificial intelligence (AI) is having just such a moment, with generative AI rocketing from obscurity to ubiquity in less than a year. But for all of the headlines, our understanding of AI suffers from farsightedness: the future seems clearer the further away it is, while we struggle to see what’s right under our noses.

Authors Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans and Avi Goldfarb describe this moment as the “between times”, in which we have only begun to understand the technology’s future potential but have not yet seen its widespread adoption. Make no mistake, Chatgpt is only the Ford Model T of AI. It’s the popular, early precursor foreshadowing the discrete and world-changing movement revolution to come.

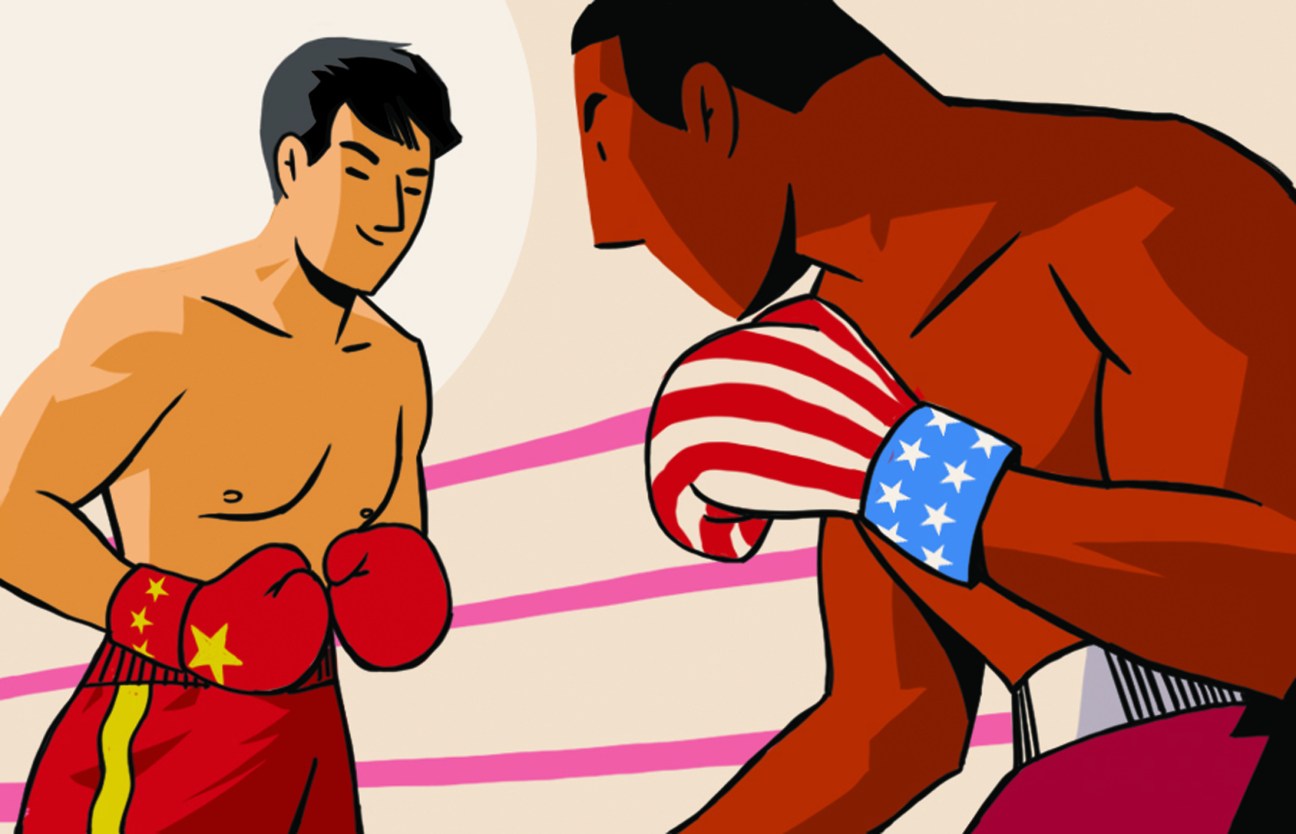

One underestimated fact is how global politics – the decisions being made by governments today – will influence AI’s trajectory; decisions that in turn will determine the future of work and jobs across the world. While some countries are scrambling to secure advantage, others are seeking simply to stymie opponents. At the end of 2023 this is most apparent in the worsening US-China relationship, where critical and emerging technologies are a key battleground. The US-China economic decoupling is in turn upending longstanding assumptions about globalisation and co-operation and giving way to new rules.

There are four elements to watch for geopolitical competition when it comes to AI. They are data, computing power, energy and talent – and here’s why they matter.

1.

Data is the rocket fuel powering AI training – the process by which a model is taught to perceive and analyse information. The more quality data that a model is given, the greater the effectiveness and accuracy of machine learning. However, efforts by governments to keep data “local” will saddle companies with burdensome compliance rules and slow progress.

2.

Computing power is the ability to process information at scale. AI training depends on the use of the most hi-tech silicon chips. Developments in computing power have been the main driver of AI’s rapid progress over the past decade. The US has temporarily curbed Chinese access to advanced chips and chipmaking equipment, while China has sought workarounds and poured money into domestic r&d.

3.

Energy is an often-overlooked geopolitical factor, but AI’s future energy requirements will only grow. Computing power is projected to reach 21 per cent of global electricity consumption by 2030 (up from less than 2 per cent in 2018). Training OpenAI’s gpt-3 required a staggering 1,285 mw/h in electricity and emitted more than 550 tonnes of carbon dioxide, which only hints at further questions about AI’s environmental cost.

4.

Finally, the global AI talent pipeline will establish which countries and companies get ahead. Talent takes investment and time to grow. While the US has the greatest concentration of skilled top AI researchers, China has intensified its talent attraction, retention and training efforts. Today more than 440 Chinese universities offer AI degrees.

These four bottlenecks will influence how rapidly AI can scale in future. What’s clear – regardless of which countries get an edge over others or the speed at which it happens – is that a growing percentage of workers will be displaced by AI. Who and how are only just starting to become visible.

The Hollywood writers and actors strikes offer an early clue for how AI will soon affect jobs.

A decade ago, the narrative about the future of work was that automation would replace routine prevailing and administrative roles, leaving humans to focus their energies on more creative and complex tasks. In a 2013 study, Oxford economists Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne estimated that 47 per cent of jobs in the US were at risk from automation, noting that highly skilled jobs were likely to be the least susceptible to disruption.

But generative AI’s deftness in tackling the creative industries through high-quality text, image and even video generation has spun that assumption on its head. Generative AI can outperform humans in computer coding and can even predict sophisticated protein structures, the latter of which could only be done previously through experimental deductive techniques. In fact, Frey and Osborne recently acknowledged that lower-skilled workers might stand to disproportionately benefit from generative AI by levelling the playing field. In contrast, highly-skilled incumbents may soon find their advantages – and wages – whittled down, overwhelmed by a tsunami of AI-enabled competition.

It isn’t all good news for low-income workers, though. There is already an AI underclass in places such as Kenya, India and the Philippines. In these countries, armies of so-called “data annotators” – workers tasked with supplying algorithms with brutal and graphic content to moderate – are subjected to poor conditions and frequent assaults on their mental health, in exchange for low wages and little support. A recent Pew study also found that one in five US workers have “high exposure” to the effect of AI, whether negative or positive – with female, Asian, college-educated and higher-wage workers all particularly vulnerable.

Nevertheless, humans are notoriously resilient and resourceful. We can spy hope in places such as a recent study from mit economist David Autor, which draws attention to the common-sense observation that 60 per cent of workers today are employed in jobs that didn’t exist 80 years ago. So perhaps it’s a matter of perspective. Rather than focus on the loss of jobs today, we should perhaps focus on new avenues for jobs – ones we have yet to invent or imagine. And if Amara’s Law is anything to go by, we still have a little time to think it through.

About the writer: Young is a senior geo-technology analyst with political risk consultancy firm Eurasia Group and a juror for the Balsillie Prize for Public Policy.

Ahmed Al Omran on …

Why, even though Saudi Arabia is longing to tempt foreign investment and has cut red tape for start-ups, its powerful public sector is crowding out private business.

US tech giants such as Google, Amazon and Microsoft dominate the world’s attention and the global economy. But what do they have in common? Among other things, they all began in garages: a founding myth that’s given them a special place in the imagination of would-be entrepreneurs.

Saudi Arabia took that precedent literally and decided to build one of its own to help tune up the national economy. The Garage is a co-working space in a revamped car park in Riyadh’s King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology. There are shared office spaces, conference rooms, an events area and even sleeping pods for naps. Launched in 2022, the project was expanded in September 2023 and is an illustration of the country’s desire to wean itself off its dependence on oil revenues by tempting technology start-ups to the country.

Seven years ago, Saudi Arabia unveiled its plan to supercharge the economy by limiting the role of the wealthy public sector, letting the private sector lead economic growth. It restructured government departments to attract foreign investment, updated its laws and regulations and sent delegations around the world to entice investors with incentives. Red tape was cut: waits for business visitor visas were shortened to 72 hours. There are reasons to be positive too: neighbours with larger populations, such as Iran and Egypt, are drowning in political and economic turmoil, while the populations of Gulf neighbours including the uae and Qatar are too small to support growth. Despite its social conservatism, Saudi Arabia is one of the world’s biggest 20 economies and has a young and affluent population. In truth, the slow speed of growth is partly self-inflicted. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has overseen some easing of strict social laws but his anti-corruption clampdown in 2017 and the killing of Jamal Khashoggi the following year have scared some investors away. Foreign direct investment fell 59 per cent in 2022 to €7.5bn, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

While foreign investment has faltered and oil prices bounced, Saudi Arabia chose to lean into its own resources: the Public Investment Fund (pif). The state’s sovereign wealth fund started more than 70 companies with hundreds of billions of euros in investments, ranging from a science-fiction grade futuristic city called Neom (to be built from scratch in the country’s northwest) to a dairy firm specialising in camel milk, among others.

The rise of the sovereign wealth fund, with its expanding list of investments, has raised eyebrows among some investors who say that the fund – and its sizable war chest as a result of transfers from the state treasury – is crowding out the private sector that the country says it is keen to bring in. Officials say that the pif focuses on risky and strategic sectors that private investors have little appetite for. That argument holds water for defence or infrastructure, it’s less convincing when it comes to camel milk.

Authorities claim that the overhaul of laws and regulations is working. The Saudi Ministry of Investment says that it issued 4,358 investment licenses in 2022, a 54-per-cent jump on 2021. How many of those licences will turn into sustainable businesses, however, remains unclear.

As much as the kingdom yearns for the private sector to take the initiative and lead the economy, the public sector continues to dominate – and while it does, entrepreneurs are at a relative disadvantage. The Garage’s relaunch event in 2023 was a case in point. Images from the opening bash feature far more government officials than venture capitalists or start-up founders. If the kingdom is to become a genuinely competitive place to do business, it needs to strike a better balance in 2024.

About the writer: Al Omran is a Saudi journalist. He is a former Knight-Bagehot Fellow at Columbia Journalism School.

Joanna Chiu on …

The US-China trade war and why American aggression in guarding chip technology is heightening tensions around Taiwan. Is 2024 the moment to tone down the chip chat?