UBS-sponsored-content

Tailored to every client

Dylan Chong

Director and trouser-cutter, Dylan & Son

Whether you are there to fix a button or commission a bespoke suit, Dylan Chong will attend to you. The Dylan & Son director’s highly personalised approach is central to his business. “The very nature of tailoring is a long-term relationship built on familiarity,” he says. True to his word, Chong sees every client personally – and only takes up to three appointments in a day.

In a world where personal connections are rare, Chong’s dedication to understanding his clients stands out. He offers two services: made-to-measure or bespoke.

Since taking over his father’s business in 2010, Chong has maintained a tight-knit operation: a three-person team, each specialising in cutting trousers, shirts and jackets. This division of labour ensures precision and expertise, allowing Chong to focus on his customers. “Do you make a suit for your client or make a suit that pleases you as a tailor?” he says. “You have to let go of your ego as a creator because the suit is not for you.”

Like many in Singapore, Chong believes the value of his craft lies in offering bespoke pieces that differ from what’s readily available in other parts of the world. “The feeling of having something made just for you is invaluable because you don’t find it easily,” he says. “You really need a relationship with your tailor to experience this feeling.”

The right tailor is not easy to find, admits Chong. “Sometimes a person comes to me and says that they’ve gone to 10 tailors and still cannot find anything they like or enjoy wearing,” he adds. “If I can identify and solve the issue then I could be their eleventh – and last – tailor.”

If you’ve been searching for the perfect fit, reserve an appointment with Chong at his workshop at 161B Telok Ayer Street, Singapore 068615.

dylanandson.store

Room to grow

Richard Hassell

Co-founding director,

Woha Architects

The raison d’être for Woha Architects is building a better future. This is underpinned by the studio’s unerring ability to find connections between different systems, whether that’s creating habitats or reducing urban heat. “Our projects are interventions into the physical environment so we always try to see how we can create as much good out of them as possible,” says co-founding director Richard Hassell.

As global cities continue to grow, Hassell believes that integrating greenery into the built landscape is key. “We can be unaware of what’s going on beyond the city, the parts of the planet that are being degraded or destroyed,” he says. “Bringing nature into urban spaces helps foster people’s appreciation for it.”

Woha has achieved this to great effect at Pan Pacific Orchard in Singapore. Four open-air garden terraces with more than 10,000 sq m of foliage comprise three times the footprint of the 23-storey building. These green spaces play a role in elevating the guest experience. “Set in a city where most buildings are struggling to find enough room, these multi-purpose park spaces are a canvas for unique experiences to emerge, as they have not been tightly programmed,” says Hassell.

Woha has an established interior design practice too. Woha Being collaborates with best-in-class makers around the world, including The Rug Maker and Industry+.It feels like a natural extension of Hassell’s passion for craftsmanship, an affinity that was nurtured from young by his woodworker father. “There’s a real value in making things beautifully with care,” he says. “It’s part of what makes us human.”

Book into one of several Woha-designed properties when you’re in Singapore: Pan Pacific Orchard, 21 Carpenter or Parkroyal Collection Pickering.

woha.net

Playing to your strengths

Morgan Yeo

Co-founder,

Roger&Sons

When Morgan Yeo took over his father’s carpentry business in 2014 with his brothers Lincoln and Ryan, the trio had their work cut out. The business wasn’t fulfilling its potential so Yeo gambled on a change of tack. “We wanted to take on projects that most local carpenters would have rejected,” he says. As much of the industry focused on applying laminates over plywood structures, he saw an opportunity to create bespoke objects.

Roger&Sons has since created everything from a levitating shaving brush to a wooden playground, each afforded the same care and intention. Yeo’s creative process is built around collaboration: listening to his client’s needs and bringing their vision to life. He likes to guide his client on this journey, making something that holds deeper meaning to them.

This approach led Yeo to create The Local Tree Project, a ground-up initiative that salvages trees felled for urban development. He saw a through-line towards constructing sustainably: utilising these discarded timbers for his projects would mitigate an industry-wide reliance on wood imports. Today, 80 per cent of Roger&Sons’ work involves wood from Singapore including Tembusu and African mahogany.

A decade on, the family business is in a vastly different shape but the Yeo brothers have remained faithful to their core mission. “My dad instilled in us a belief to be a better carpenter every single day,” says Yeo. “We’re continually pushing our craft forward and making everything with love.” A difference that hasn’t gone unnoticed among their clients.

Roger&Sons’ creations are found across Singapore, including tables in The Macallan House and furniture at Italian restaurant Fico. Visit the showroom and workshop at 115 King George’s Avenue, Singapore 208561.

rogerandsons.sg

Heritage and innovation

Hans Tan

Founder,

Hans Tan Studio

What seemed like a weakness in university shaped the pathway for Tan to think conceptually and tinker with innovative techniques, like the Pour Table, a resin side table created without using a traditional casting mould.

After months of experimenting with additives that altered the resin’s viscosity, he developed a method to achieve a seamless surface. Tan’s inspiration was a quotidian Singaporan scene – the making of kueh lapis sagu, a traditional steamed pastry – which demonstrates his unwavering vision to uncover everyday processes and objects in a new light.

Tan’s groundbreaking inquiry into porcelain design caught the eye of the team at Mandarin Oriental Singapore, who commissioned him to create their signature Lion City fan emblem for the hotel’s lobby.

While Tan is continually seeking new ways of making, heritage and culture still stand at the heart of his oeuvre. “Design goes beyond utility,” he says. “It shows us how people in the past have lived and, ultimately, tells us who we are.”

Tan’s knack for melding the old and new provides a glimpse into where Singaporean design and creativity is headed. He puts it perfectly: “We may be a young nation without ancient traditions, but we’re great at reimagining and reinventing the old for the generations to come.”

Find Hans Tan’s works at the Supermama flagship shop at 213 Henderson Road, Singapore 159553.

hanstan.net

Finding a common language

Johari Kazura

Founder,

Sifr Aromatics

Johari Kazura smells great. The third-generation perfumer hails from Singapore’s Kampong Gelam, a cultural enclave with enduring ties to the early 20th-century spice trade. It was this neighbourhood that laid the foundation for traditional aromatics to bloom in Singapore.

While his father still has a shop rooted in Arabian perfumery, Kazura decided to create an offshoot brand, Sifr Aromatics, that distils the best of Eastern and Western approaches. “I wanted to step out of the confines of a family business and try different ideas,” he says. This venture was the fruit of his European adventures, where he trained in Grasse, France – the perfume capital of the world.

Sifr, which means “emptiness” in Arabic, was his way of starting anew.

Perfume-making at Sifr is a boundlessly customisable experience, where Kazura will help sift through your favourite olfactory memories, preferences and ingredients. It’s a tailored process where he iterates with intention, a skill he picked up from his father but honed with time. “‘Fresh’ could be used to describe different things to various people,” he says. “It can refer to mint, citrus or even fresh bed sheets, so I always seek to find a common language.”

One thread that binds the experience is Kazura’s quality natural ingredients. His family ties means access to premium raw materials. “Great ingredients have long flowed through this island,” he says. “That was how my grandfather got some of the best patchouli and vetiver.” This city-state may be a tiny island, but it’s a greenhouse where ideas and ingredients converge – the perfect nexus for Kazura to sniff out new traditions of scent-making.

Create your own bespoke fragrance at Sifr Aromatics, 42 Arab Street, Singapore 199741.

sifr.sg

Creativity without boundaries

Ng Si Ying

Rattan weaver,

atinymaker

It is fascinating to watch Ng Si Ying as she weaves: the rattan strips passing this way and that, feeding one under here and crossing the other there, as vine becomes weft, warp, knot, geometry and then beauty.

Ng’s foray began with an apprenticeship at Chun Mee Lee, one of the last remaining rattan shops in Singapore, where she worked on chair restorations. “I felt that there was a lot more that could be done with rattan than what we were doing in the shop,” she says of the dying trade.

“I wanted to know how much I could push the material so I began wondering how many ways I could weave using rattan and how many ways there were to wrap an object.”

This curiosity led to the Rattan as Wrap and Rattan as Weave projects, where Ng, who also works as a digital UX designer, creates intricate designs. She often begins by looking for a weave to replicate. “If I can’t find instructions, I will reverse engineer it from the image,” she says. Once figured out, it becomes a base for further exploration. Ng experiments with variations in colour, layers, width and design, discovering new compositions both by instinct and by chance. In documenting her explorations, she is helping to not only preserve this ancient craft for future generations but also show its true possibilities.

A wide range of clients have taken notice, from luxury houses such as Hermès to an individual from London who sought a repair to a beloved figurine. These surprising requests are nicely expanding Ng’s passion project of finding new uses, aesthetics and meanings for rattan. “I love that there are no boundaries,” she says.

Make an appointment with Ng at her home studio in Jurong East to see her latest handiwork, including the ‘Rattan as Weave’ collection.

ngsiying.com

A hunger for knowledge

Lee Yum Hwa

Founder and chef,

Ben Fatto 95 and Forma

Anyone strolling down leafy Tembeling Road in Singapore’s Joo Chiat neighbourhood might stop to gaze through a window at a small team of white-clad figures measuring flour and rolling out dough. This is Forma, the first restaurant by chef-founder Lee Yum Hwa, who made his culinary name with private dining establishment Ben Fatto 95. Both focus on fresh, handmade pasta in all its glorious forms, from classics such as spaghetti to obscure, hyper-local shapes that Lee discovers on research trips and apprenticeships in Italy.

Ten years ago, Lee was an accountant; a fateful meal in Bologna – fingernail-sized tortellini, shaped with more finesse than anything he’d seen in Singapore – convinced him to retrain. “The manual aspect really drew me in,” he says. “Every piece is made by hand, and the beauty is that it differs from each pasta-maker.”

Forma’s menu includes a changing array of pasta dishes that many Singaporean diners will be encountering for the first time. For patrons who reserve an evening at Ben Fatto 95 – a private, fixed-menu dinner where Lee cooks, serves and pours the wine – the experience is even more immersive, with an interactive session allowing guests to try making their own pasta.

Lee’s dedication is palpable – he kneads pasta dough every day to ensure perfection. And while he has a near-encyclopaedic knowledge of his craft, the sheer richness and diversity of the pasta world spurs him on even further. “The learning aspect was really driven by my hunger and my curiosity to learn every shape there is,” he says. “You can never be a master of pasta. There’s always something to learn.”

To sample Lee Yum Hwa’s pasta skills, visit Forma at 128 Tembeling Road, Singapore 423638 or make a private dining reservation at benfatto95.com

A hands-on approach

Michelle Lim and Ng Seok Har

Founders, Mud Rock Ceramics

“When you pick up one of our pieces, you know it was made by a person not a machine,” says Michelle Lim, co-founder of Mud Rock Ceramics. “It would never be so refined otherwise.”

The studio’s work is, quite literally, fit for a queen. Mud Rock Ceramics made a tea set as a state gift for Queen Elizabeth II’s 90th birthday. Nevertheless, when Lim and co-founder Ng Seok Har left their careers in design and banking to set up the studio in 2013, they could hardly have imagined that their craft would one day contribute to the delicate work of international diplomacy – or that so many of Singapore’s best restaurants would use their handmade tableware.

“What we need now more than ever is the human touch,” says Lim, who holds a degree in ceramics from The Australian National University. Mud Rock’s philosophy of making things by hand resonates with many Singaporeans who attend their pottery classes, which are held in the studio’s new space at Tan Boon Liat Building, the city’s unofficial furniture hub. The industrial unit is furnished with Mud Rock originals and fronted by a stunning tadelakt wall – a textured Moroccan plaster finish that speaks to Lim and Ng’s earthy, hands-on approach.

In a city as fast-paced and modern as Singapore, the pair’s commitment to slow-making is a refreshing counterpoint to the hectic nature of daily life. “Craft teaches discipline and patience,” says Ng. More than just beautiful objects, Mud Rock’s work is a physical reminder of the value of taking a more considered approach to the world.

Get to grips with clay at a class or course in Mud Rock Ceramics’ new studio at Tan Boon Liat Building, 315 Outram Road, Singapore 169074.

mudrockceramics.com

The craft of what comes next

Dr Laura Sutcliffe

Healthcare analyst

Based in Sydney, and with UBS since 2019, her role as head of Australian healthcare equity research involves deep analysis and number crunching. She might be listening to a big reveal at a medical conference or talking with doctors, all of which helps her form an expert opinion from the deluge of data about what trends to follow and where stock prices are going.

What does your day-to-day role involve?

Helping our investors identify opportunities, either to buy or sell a stock, in the healthcare space in Australia. My day-to-day job involves looking at pipeline technologies and seeing how they are gaining traction in the healthcare community. We might talk with physicians or patients, and also work with companies that make these things, to understand how they’re making decisions about the future, how they might look to develop new tech or drugs, and then form an opinion on the share price based on that.

It sounds like a balancing act, no?

Stock picking is a balance between the science end and the art of understanding how those technologies are going to impact the market, knowing how to interpret the signals for what people might want, and where the need is. So how are these things going to sell? There is a certain angle to it that is an art and not a science, so I’m balancing both.

Your job is to analyse statistics but there must be an important element in building relationships?

Ultimately making these judgments is about the relationship between the technology and the people. You can have fabulous technologies – we often see this in med tech – but if people don’t want them, there’s a limit to how much impact they ultimately have. Trying to get into the weeds of the relationship between the people and the science is something that’s unique to individual analysts as well. So, if you were to look at my peers across the healthcare space, the way they choose to go about evaluating those opportunities is very individual. So maybe you get people who really can discern the signal from the noise by being heavily numerical. Other people lean more on what they hear from doctors.

What makes you stand out as an analyst?

I’ve now covered major stocks in the US, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region so the first thing that I bring is a global view. But it’s not just about what I bring; I’m also part of a healthcare ecosystem or family here. What I bring to my team – and what we do together – is a kind of craft.

What are some of the new frontiers in healthcare?

The healthcare space has a lot of work to do in neurodegeneration and that’s one of the next frontiers that we’ll be confronting. You can see some of the work that’s been done in things like Alzheimer’s disease but we’ve still got potentially quite big strides to make before we can declare any kind of victory.

So, your job is to speculate on the future?

It’s an art form because it’s about learning to distil things that are complicated in a way that is not only understandable and meaningful, but also investible. And sometimes a concept can be very intriguing and very satisfying to understand – but it’s not necessarily an investible one.

The craft of shaping evolution

Dr Jordan Nguyen

Biomedical engineer and inventor

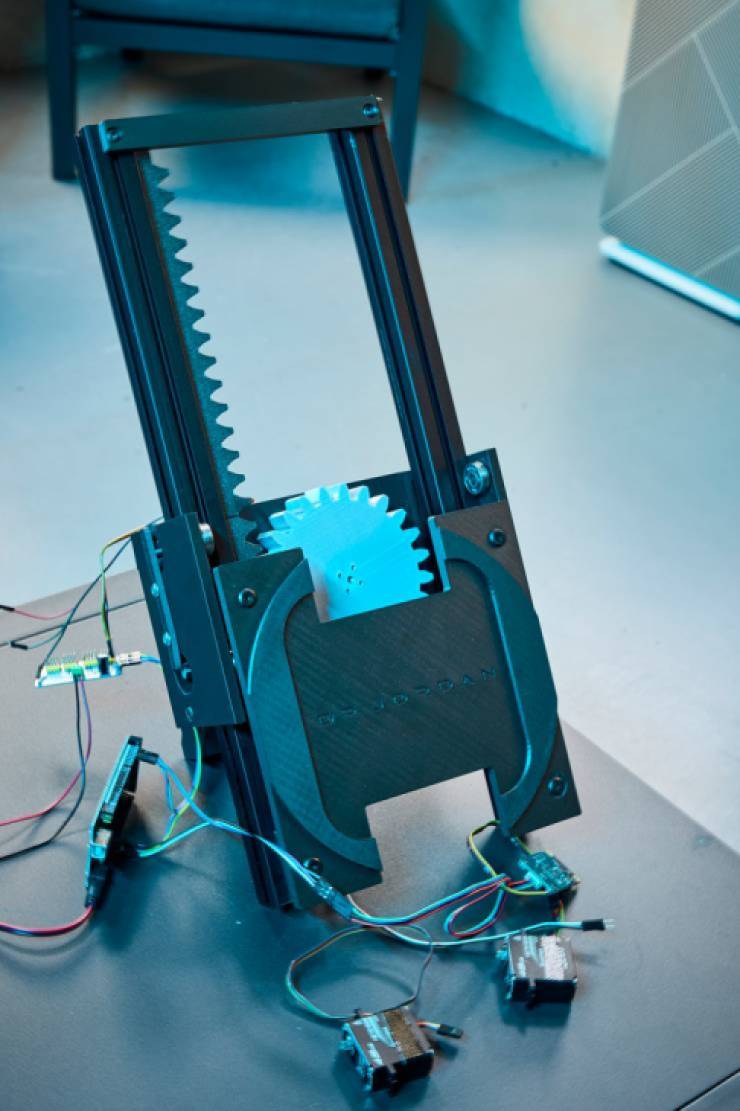

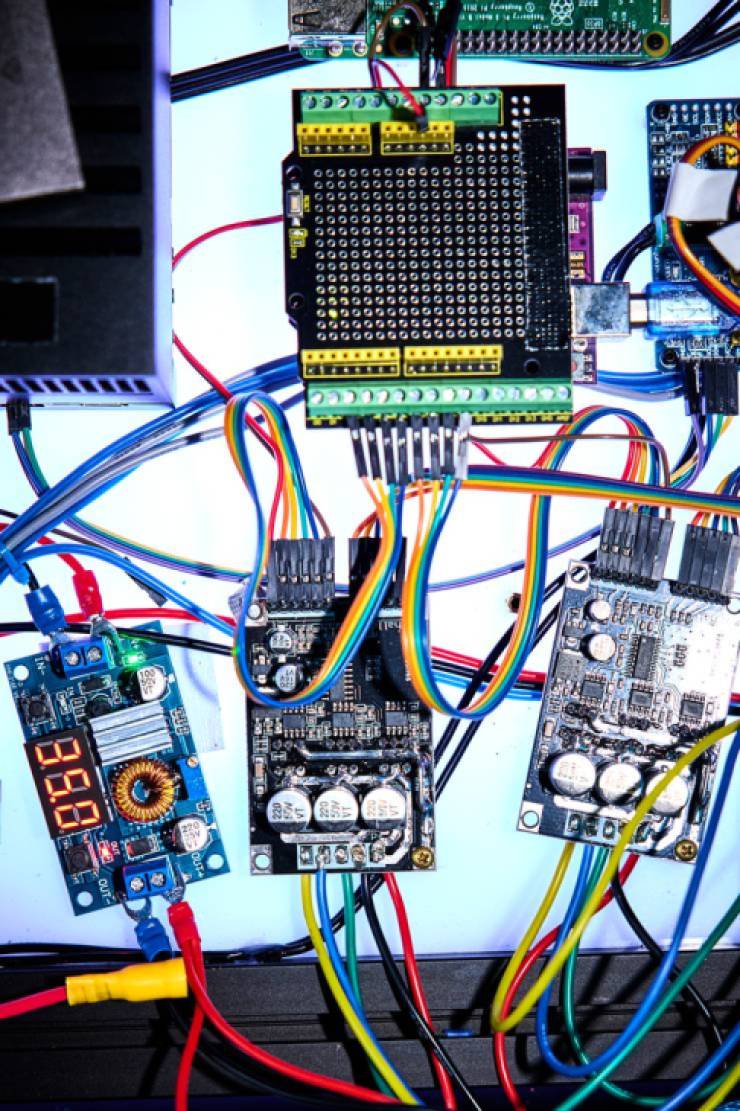

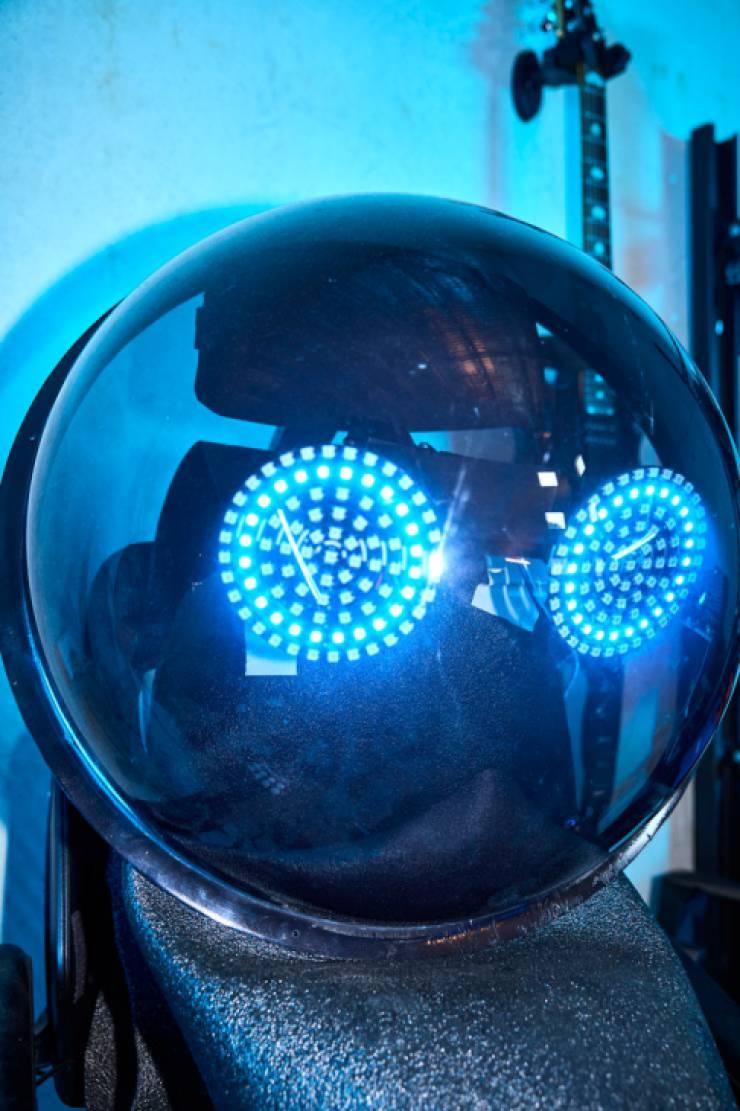

Born to an engineer father and artist mother, Australian-Vietnamese futurist Dr Jordan Nguyen grew up surrounded by robots and paintings, leading to a deep understanding of how science and art can work together to make something extraordinary. Nguyen is the founder of Psykinetic, a technology company that uses AI, robotics and a keen sense of design to create accessibility-enhancing devices such as mind-controlled wheelchairs.

When you’re working on a new project, do you start with the research first or envisioning the final product?

I was always a daydreamer and told I needed to stop daydreaming in class at school but it turned out to be a really great skill. I can visualise entire ideas and how they’re going to be at the end. Even now, with all the different things that I’ve built, I will still start projects where I know about 10 per cent of how to do it. I always do a little bit of research. But usually I know that the projects I’m building are pretty ambitious and they haven’t been done before. So I form my own idea of what I want to be able to build – and I just get started.

How has the advancement of technology helped your design process?

The tools available are more abundant and the knowledge is more open. We’ve got things like open-source code now and it feels a lot more like an artistic outlet than before. When it comes to the electronics, the software, the construction and the mechanical side, all of it feels like creative expression now. With things like my robots, it’s not just individual components all moving together; you also want to be able to give it a soul. The ideas come from a level of purpose, which comes from inspiration. And inspiration to me always comes from seeing things in the world that I would love to see – a solution that could improve quality of life, whether that be for friends and family, or for something bigger.

What roles do craft and design play in your engineering?

The commercial version of our eye-controlled keyboard looks like an absolute space-age device; it’s so beautiful. There’s so much to the aesthetics and the flow of the design. Traditionally, a lot of accessibility devices have been pretty terrible-looking, and they’re very expensive and clunky. What we’re going for is something that is so adaptable and is so able to be personalised – you can change the colours, the lighting, the fonts – that it allows you to express yourself the way you want. A beautiful device can completely change the paradigm of assistive or inclusive technology. It’s much more than an add-on or afterthought. It’s something that can be built into the core of a product, and it really helps with getting across the vision, the dream and the message of why you’re doing what you’re doing.

How can aspiring inventors cultivate a sense of innovation?

There are so many things that have already been built and tools that we can harness, so to achieve new ideas you can often start by piecing together things that are already there and then add that extra leap. Invention, which is pure creation, is more difficult. But innovation opens up new spaces of opportunity for people to come in and try new things. There is an amazing wealth of tools available for us to achieve any idea that we set our minds to. The truth is, I’m not surprised by things any more. Anything is possible.

© UBS 2024. All rights reserved. Disclaimer: Dr Jordan Nguyen is not affiliated with UBS AG.