UBS-sponsored-content

The craft of making better decisions

Niall Macleod

Research leader

Global financial markets never sleep so investing in them successfully requires an agile, proactive approach based on international research and insight. Niall MacLeod has been honing his craft in this respect for more than three decades. Having joined UBS in 2008, he is currently APAC head of product management, UBS Research. “We’re trying to interpret what’s going on in the world in a way that helps our investing clients make better decisions,” he says.

When you talk about innovation in finance, how much of that involves predicting the future?

It’s a combination of things. Part of our work is trying to assess what is going to happen in the future. Part is about providing roadmaps, a thought process and a framework that helps our clients reach better investment decisions. We innovate a lot in techniques that will help us make better decisions and think about what our clients are going to need. UBS was very innovative about 10 years ago in creating UBS Evidence Lab, which collects all sorts of non-traditional information such as geospatial analysis, surveys or uses other novel techniques to help assess pivotal investment questions in a market or sector, for example: tearing down an electric vehicle, to better understand the supply chain and help identify who the winners might be from the rise in EV penetration.

How do you balance introducing innovations with maintaining a corporate framework?

We don’t want to be an organisation that doesn’t allow for challenge because if everyone just believes the same thing and turns out to be wrong, you’ve got a very serious problem on your hands. Challenge is critically important to the sustainability of a good financial services organisation.

How important is knowledge sharing?

One of the incredible strengths of UBS is the fact we have extraordinarily good communication and collaboration between people. It’s really part of the DNA of this organisation. Within research, we have 700 analysts, strategists and economists around the world with whom we have a very open dialogue. Trust is a critical part of communication. I don’t fear if a colleague in the US or Germany or India calls me out on a view, I don’t feel that it is a personal affront. I know it’s being done because we’re trying to reach a better decision.

What is the most underappreciated aspect of the craft of banking?

Financial services and banking in general involve risk and often high degrees of complexity. Managing that sustainably is all about having the right culture. What is underappreciated are the enormous lengths to which we go to ensure that we have the right culture; one that focuses on the long term, encourages collaboration and innovation, fosters challenge, and, most importantly, puts our clients at the heart of what we do.

Away from banking, where is the greatest potential for innovation?

AI has created enormous excitement. While there will be huge innovations in critical areas like the environment and tackling climate change, I’m particularly excited by what it could do for healthcare: more rapid drug discovery, enhancing our understanding of our physiology and exciting breakthroughs and insights into our own minds. And ultimately, people being able to live healthier, happier and longer.

The craft of enhancing human experience

Dr Amy Kruse

Neuroscience investor

As our understanding of the brain advances every year, Kruse leads the way in identifying new opportunities while investing both capital and expertise to help them flourish.

What brought you to neuroscience?

It was a personal interest. My parents were English teachers but I was a real scientist. They got me a microscope and the rest is history. I think biology is romantic. It’s all about discovery and the natural world, right? And we’re developing all these tools to understand it.

Why did you decide to move into the investment side of things?

I’m a very curious, expansive person. There are people for whom working on one research problem is quite satisfying but I always found myself drawn towards those broader perspectives where you can connect the dots. And then, as an investor, I do believe that neurotechnology is such an incredibly explosive and growing area. This is the right time to be deploying capital in this space.

What is your investment priority: transformational potential or financial gain?

I try to hold all those things together. When you’re looking at venture investing, you are looking for outsized returns and so there’s a kind of calculus between market potential and a transformative or unmet need in that space. And then it’s really an engineering question: can we take this concept or this thing that we’ve proved in the lab and turn it into something that would be scalable?

How have some of your investments helped to enhance the human experience?

There are a couple of different types of investments that I’ve made that do that. Some are in the mental health space but relate to what’s happening in psychedelic medicine. When I was a graduate student, it was thought that the adult brain was quite fixed and it really couldn’t be changed very much. And now we know that there are myriad ways of inducing neuroplasticity and helping the brain to change. So, we’ve been looking at techniques and tools that that help us heal, learn new skills or work on cognition.

How have you honed your instincts for a good investment?

I’m seeing what’s coming along, I have other CEOs in my network who are introducing me to folks, and I’m very fortunate that there is a flow of opportunities and ideas.

You’re an avid gardener. What lessons learned from nurturing plants have you applied to your day job?

The reason I garden is because I like putting my hands in the dirt, it is really one of the only things that calms me down. We all need things that keep us grounded. Certainly, that’s the case in investing, where things can get pretty out of control. I also love the fact that there are cycles and seasons – there are absolutely ebbs and flows to investing in companies. And if your plant dies, you simply start over with another seedling. It is truly one of the things I love about gardening: “It didn’t work? OK, tomato, we’ll give it another shot.”

© UBS 2024. All rights reserved. Disclaimer: Dr Amy Kruse is not affiliated with UBS AG.

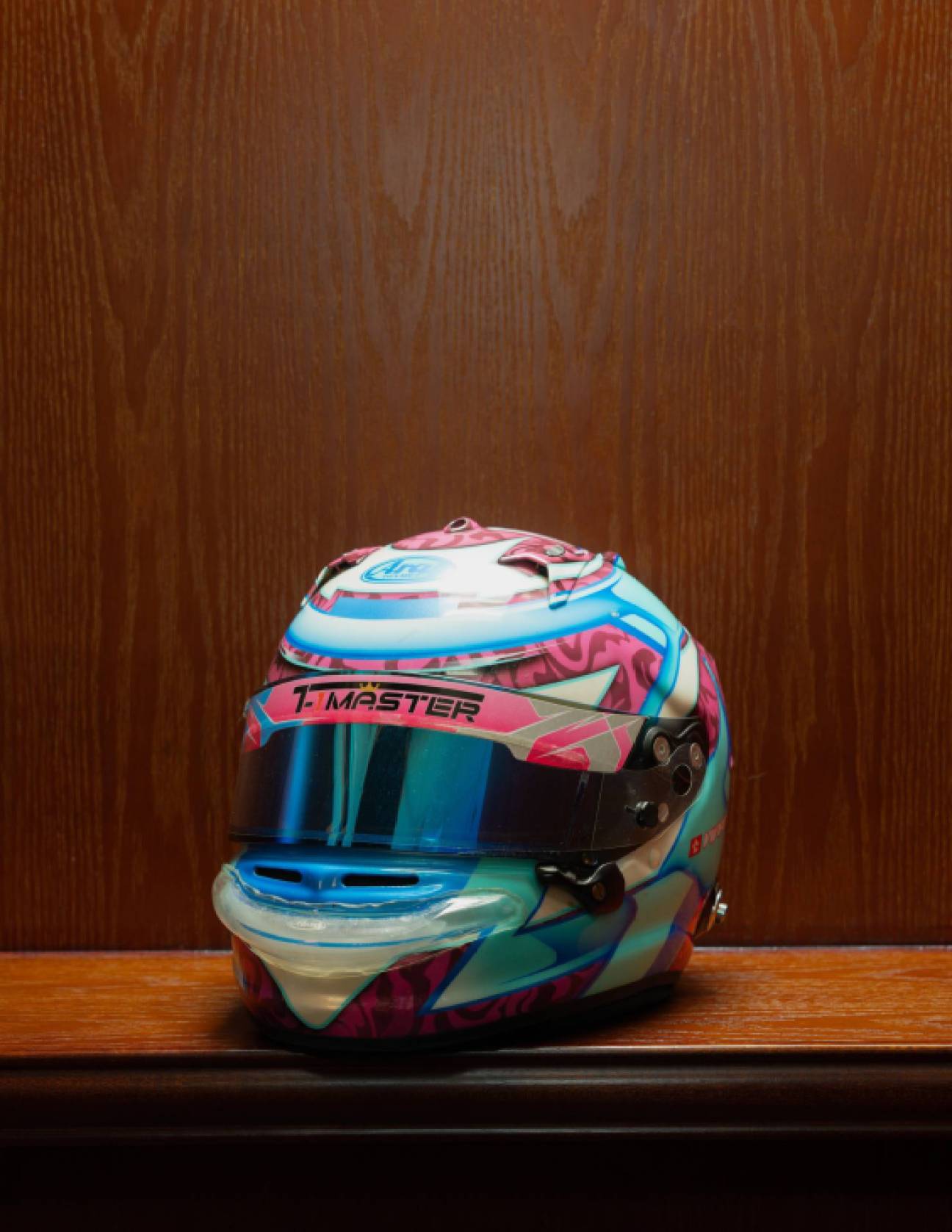

The craft of blazing a trail

Vivian Siu

Racing driver

Hong Kong-based Vivian Siu is a director of hedge fund origination sales at UBS. But that’s not the only place where she’s been testing her quick wits. Last year, Siu decided to fulfil her childhood dream of becoming a Formula 4 driver, despite having no prior racing experience. Training in her spare time, she set her sights on competing in the Macau Grand Prix. Her story has been turned into a forthcoming documentary, Zero to Macao.

What suddenly made you decide that becoming a racing car driver was something that you needed to do?

I’ve always been into cars but I never had the chance to explore racing. When I was younger, I couldn’t afford to try out motorsports so I didn’t think about exploring this hobby until now, with the finance career that I have. During the pandemic, we didn’t get to travel outside Hong Kong for three years. So, when the borders reopened last year, I just wanted to do everything at once. That’s when I decided that I really wanted to give it a try and test the waters with the help of my team, T-1 Racing. When I first started testing the car, I didn’t expect the trajectory to end up the way that it has. Everything happened by chance and whenever there was a new opportunity, I just seized it.

Are there crossovers between the worlds of Formula 4 racing and finance?

Finance is a male-dominated industry, just like racing. I was the first female Formula 4 racing driver in China so I definitely saw some similarities with the world of finance. There are a lot of other perspectives as well. For example, in finance there are a million bits of information being thrown at you at the same time. When you are communicating on the radio in the car, there are a million bits of information being thrown at you too. It takes a lot of skills to listen properly and adapt on a very quick level. That’s what my job in finance also requires me to do.

Are you hoping to inspire other women to follow in your footsteps?

When I first started the journey, I did not expect someone like me to be a person who could open pathways for others. That comes with pressure, yes, but at the same time I wanted to give my all out there and not really care about the outcome too much. Representing is what I am trying to do.

Motorsport – the power of a machine with the precision of the human touch – is a craft in its own right, isn’t it?

Formula driving is another level, compared to other types of racing. It is the one that’s the most technical and requires the widest skillset. When we talk about racing, and the craft of Formula racing, it’s definitely the pinnacle of motorsports. Because one tiny mistake – let’s say you step on the brake a little harder than you’re supposed to – and you could lose the car. It’s a no-margin-of-error type of driving and it requires a lot of focus.

Is there more that you want to achieve in motorsport?

From the first time that I sat inside a Formula 4 racing car until the Macau Grand Prix last year was a span of just six months. And I haven’t done any racing since that time because I think that was the climax. It has been an incredible journey.

The Story of Craft: Shaping A New World

In our latest series, we are widening that scope to industries as varied as healthcare analysis and neuroscience. These are designers of a different sort: innovative leaders in their respective disciplines who are mapping out the world and equally invested in shaping its future.

Indeed, when you distil craft to its essence, that’s what it is all about: forging a unique path, no matter the challenges along the way. Whether it’s seeing patterns in complex data or navigating the perilous corners of the Macau Grand Prix circuit, our interviewees are united by their ability to take technical rigour and turn it into an art form. They are the very embodiment of craft.

The craft of blazing a trail

Hong Kong-based Vivian Siu is a director of hedge fund origination sales at UBS. But that’s not the only place where she’s been testing her quick wits.

The craft of enhancing human experience

With a PhD in neuroscience, Dr Amy Kruse is the chief investment officer of Satori Neuro, a division of the Texas-based hedge fund Satori Capital, which invests in innovative neurotechnology companies transforming how we…

The craft of making better decisions

Global financial markets never sleep so investing in them successfully requires an agile, proactive approach based on international research and insight. Niall MacLeod has been honing his craft in this respect for more than…

The craft of shaping evolution

Dr Jordan Nguyen is the founder of Psykinetic, a technology company that uses AI, robotics and a keen sense of design to create accessibility-enhancing devices such as mind-controlled wheelchairs.

The craft of what comes next

Dr Laura Sutcliffe’s job involves advising investors about where the healthcare industry is heading.

Monocle and UBS, a bank tracing its history back more than 160 years, have been jointly exploring the notion of craft and what it means in today’s world.

Pushing the boundaries of flavour

Basil Willi, Flurin Willi, Tim Gebhardt and Timon Wolf

Founders, Kollektiv Eulenspiegel

Despite diverse day jobs, the former school friends who make up Kollektiv Eulenspiegel really shine when they cook together in their “Food Lab”, a former bakery in Basel’s Gundeldingen district.

“We craft culinary experiences,” says Flurin Willi (pictured above). “We’re not just serving food; we want to tell stories with what we serve, through presentation, preparation methods and flavours. Our favourite events happen in intimate settings.”

The young culinary group plan collaborations with local restaurants, concoct workshops and cater to private events. Building such experiences, says Willi, means adopting different roles.

“We forage for produce in the nearby forests with our truffle dog, Vayra; become handymen if we’re hosting guests somewhere without a kitchen; and, of course, there’s the culinary stuff.”

Describing themselves as detail-driven artists, the collective focuses on local ingredients and experimenting with specialist processes. “We’re nerdy about fermentation and preservation,” says Willi. “We always play with the unknown: go to the market, buy an interesting-looking vegetable and throw it in a jar with water and salt to see what happens. Maybe it explodes but perhaps it will give you the subtle tangy flavour that you’ve been missing on your cheese sandwich.”

That experimental approach is appreciated by the guests. “Isn’t it the very best feeling,” adds Willi, “to see people smile and enjoy your food?”

Images: Philip Frowein, Lukas Wassmann, Annette Fischer

Modernising a time-tested craft

Matteo Gonet

Founder, Glassworks

“Glassblowing as a craft is at least 2,000 years old,” says Gonet. “I was attracted to that tradition and to the physical aspects of it. It’s difficult to invent new ways with such an old material so it’s more about reinterpreting the techniques and shapes. And using new methods to heat the kilns.”

Much talk in the glassblowing industry today centres on the energy that you’re using, but Gonet says that this has always been important. “Today we’re moving from gas to electricity and in Switzerland we have the chance to use up to 80 per cent green energy. We have to make our process as clean as possible – that’s really important.” Glassblowing, says Gonet, needs patience and a commitment to the material. “It gives you a good reason to get up in the morning,” he adds. “I started glassblowing when I was 15 and, even now, with a full-time team of 10 people, I’m always happy to spend half my time in the workshop. “It structures your identity and your life – at least for me.”

Improving on tradition

Andreas and Charlotte Kuster

Owners, Jakob’s Basler Leckerly

Founded in 1753, the biscuit-maker Jakob’s Basler Leckerly is one of Basel’s – and, indeed, Switzerland’s – most historic companies. The core product, a gourmet gingerbread cookie, has stood the test of time, its delicately spiced variations reflecting the expansion of Swiss trade routes over the centuries.

Jakob’s Basler Leckerly’s fortunes, however, haven’t always been quite as sweet. That is, until the Kusters revitalised the company and brought in the award-winning and playful new packaging, which is proof that, sometimes, it’s not just what’s on the inside that counts.

“This all came about from a cold call,” says Andreas, of the decision to buy the business. “We were both born and raised in Basel, and when we came back to the city 10 years ago, we started looking for companies with development potential. We found Jakob’s Basler Leckerly by pure luck. It was very rundown, there were only five employees left and they didn’t own a computer. But it did have such a rich history.”

The Kusters took over in 2017. They found no consistency to the branding so set about preserving some of the original design features while creating an exciting new packaging scheme. This includes tin boxes that reference figures and sites that you can see around Basel. Quirky interactive mechanical features have made the tins as unique as both the places they invoke and the gingerbread inside.

You can find Jakob’s Basler Leckerly at Spalenberg 26 in central Basel or head to the larger branch on St Johanns-Vorstadt 47, where you can get a glimpse of the factory next door.

Defining good taste

Bettina Ginsberg and Alexa Früh

Owners, Grimsel

“In one word, Grimsel is a platform,” says co-owner Bettina Ginsberg. “We run a furniture gallery and complement our range with textiles, glass and ceramics. We’ve also started to produce our own designs with small artisan workshops, as well as sourcing unique vintage pieces. We also offer consultation on colour and interior design.”

The duo’s light-filled premises on the Rhine is the perfect setting to display their cultivated connoisseurship: they are united in their intuitive approach to quality in design and workmanship.

“Current and classic designs often reinforce each other,” says Ginsberg. “A mix should always work in a natural, spontaneous way. We have many overlapping interests but it’s always helpful to have two pairs of eyes looking at something from another angle.

“Our ideas are enriched by our different backgrounds just as Basel, a border city, is enriched by different cultures and languages. It has a certain openness.”

Ginsberg and Früh are much less guided by trends and favourite eras than they are their personal preferences. It’s perhaps why they have become Basel’s unofficial arbiters of taste.

Look out for ceramics from Thomas Bohle and Cécile Daladier, as well as hand-forged Fuschina da Guarda knives in the gallery at St Johanns-Vorstadt 38, 4056 Basel

Designs for life

Emanuel Christ

Co-founder, Christ & Gantenbein

That thinking is also evident in the elegance of the many buildings that they have created, such as the Swiss National Library and the extension of the Kunstmuseum Basel. “As our experience grows, our commitment to staying hands-on remains unchanged,” says Christ. “Hands-on work sustains our connection and relationship to the craft of architecture – and our team builds beautiful models that are integral to our design process.”

Founded in 1998, Christ & Gantenbein’s Spitalstrasse studio is no stranger to cutting-edge technology, as shown by the LED-light frieze that wraps around the new Kunstmuseum Basel building. Academic research influences the practice too and they take a holistic approach to innovation. For a new social-housing building in Paris, the team’s research on housing typologies led them to find ways to optimise light and ventilation.

Christ also remains fascinated by the technical challenges that architecture presents. “Its creative expression, its social implications, the challenges of making sensitively, sustainably and innovatively, and, of course, the need to understand both function and aesthetics.”

Christ & Gantenbein’s Basel buildings

Kunstmuseum Basel: LEDs create a striking ‘intelligent light frieze’ on the museum’s Neubau building.

Café Zum Kuss: A concrete bar pays tribute to its former life as a storage facility, while an opening connects it to greenery.

Designing a world of possibilities

Stefan Senn

Founder, TinyKüche

The driving force behind Stefan Senn’s designs has always been what the carpenter has been missing in his own life – and the realisation that others might be in need of those things too. TinyKüche, his new petite-but-complete modular kitchen system, is the latest such nook filler.

“My great-grandfather, grandfather and father were all cabinet-makers but they all came to it themselves,” says Senn. “My father went into restoring antiques and so I felt as though I already had a museum at home. I was more interested in nice, clean design – and I still am.”

TinyKüche started about a year ago when Senn needed a compact kitchen. “I couldn’t find it, so I made it,” he says. Despite the wealth of kitchens on the market, the designer felt that none was suited to a small space. Unwilling to sacrifice any of the amenities of a larger kitchen, he set about fitting everything that he could into the smallest arrangement possible. The outcome is a world-first object. “There was lots of trial and error along the way,” says Senn. “Our first sink was so small that it didn’t fit a dish.”

TinyKüche demonstrates the immense possibilities that wood provides for original design. “It’s a privilege to work with the material,” says Senn. “It brings me so much happiness. Apart from build a rocket to the moon, you can really do anything with it.”

Take a behind-the-scenes visit to Senn’s workshop overlooking the Rhine. Visit St Alban-Vorstadt 15, 4052 Basel