The deadly crash of an Air India Boeing 787 Dreamliner in Ahmedabad on 12 June – just days before this year’s Paris Air Show – ensures that the mood at Le Bourget on the opening morning is at odds with the sunny weather. Since Boeing’s CEO, Kelly Ortberg, cancelled his plans to attend and the corporation ruled out making any business announcements, attendees know that the event won’t be dominated – as it usually is – by the competition between the US manufacturer and its main European rival, Airbus. With that arm-wrestle momentarily paused, what are the great and the good at Le Bourget going to talk about this year?

As always with big commercial fairs, it helps to follow the money. With major geopolitical turbulence buffeting Europe, a huge rearmament effort is releasing a lot of money into the aviation sector. Indeed, pride of place on the tarmac has been reserved for two military planes – an Airbus A400M Atlas and Dassault Aviation’s iconic Rafale fighter jet – and some parts of the fair feel like an air-force base. Officers sporting aviators move among sprawling stands devoted to drones, missiles and radar systems, which wouldn’t have had such prime real estate a few years ago. Here’s what else is being discussed above the din of roaring jets.

Unmanned aerial vehicles

The threat and opportunity of uavs and drones hover over most conversations at the air show. “A €100 toy can now destroy a €100m aircraft,” as a European air-force officer tells Monocle. That cost-benefit analysis is reshaping procurement strategy. Drone swarms have already been tested as defensive shields for fighter jets – and are, if conversations here are to be believed, likely to become a standard operating procedure across the world’s air forces. Even as militaries scramble to adapt to the game-changing warfare being pioneered on the battlefields and in the skies above Ukraine, UAV technology is changing. “Ten years ago, we couldn’t detect anything slower than 50 metres per second,” says Eric Huber, Thales’s vice-president for surface radar. “Now we can see targets at 10 metres per second.” His company’s Ground Fire 300 radar tracks up to 1,000 simultaneous targets – an indication of how big drone swarms are expected to become.

During a Strategic Aerospace Seminar at the Hôtel de Bourrienne,Taras Wankewycz, the CEO of hydrogen start-up H3 Dynamics, argues that hydrogen-powered UAVs will redefine our understanding of stealth and endurance. “Electric UAVs are quiet and low signature but battery limited,” he says. “Hydrogen expands range dramatically.” Wankewycz tells Monocle that mobile units enabling liquid-hydrogen UAV supply will be a battlefield reality in the near future. Big players such as Airbus and Lockheed Martin are now pushing into unmanned systems, either through in-house development or strategic acquisitions. Yet many significant advances seem to be coming from software firms such as Helsing, which are marrying rapid deployment hardware with AI to speed up decision-making and co-ordination.

What was once a novelty is now a necessity. The organisers of this year’s show invited more than 100 start-ups to present what they are working on in a dedicated space. Many, such as France’s Aerix, are developing “dual-use” technologies for defence and civilian needs – from medicine deliveries and pipeline inspections to flying taxis. In the civilian space, there are still a lot of questions about regulation: how can drones and traditional aircraft share airspace safely? To what extent will authorities allow the buzz of delivery drones overhead to pervade urban life? One thing is clear: unmanned aviation, military and civil, isn’t on its way – it has already landed.

Manufacturing

With Boeing less present, Airbus is dominating the backrooms: the European giant has taken off with almost $20bn (€17bn) in deals, including prominent contracts with Saudi Arabian players such as Riyadh Air. But there are signs that the traditional duopoly is broadening as the Airbus-Boeing duel gives way to a more fragmented and dynamic landscape.

Brazil’s Embraer, already a leader in the regional jet space, is making headlines with its urban air-mobility arm, Eve, which has inked a $250m (€217m) deal for 50 Evtols (electric vertical take-off and landing aircrafts) with São Paulo-based Revo. China’s Comac C919 narrow-body jet – which has been flying over the People’s Republic since 2023 but is absent from Paris due to its lack of European certification – is courting Southeast Asian operators and quietly positioning itself as a viable third force. When it is certified in the next few years by European regulators, it could become a major player in the West, given the aircraft shortage that continues to blight the civilian flight industry. According to McKinsey, just 7,000 aircraft were delivered globally from 2019 to 2024, 5,000 fewer than projected before the pandemic. As a result of supply chain snarls, labour shortages and material delays, manufacturers and their suppliers are under immense pressure to catch up. This lag benefits leasing companies (rates for the 737 Max 8, for example, have soared by nearly 60 per cent since 2021) but hampers airline expansion.

Complaints from carriers, such as Air France, that European regulations are putting them at a structural disadvantage against state-backed competitors – combined with the fallout from transatlantic tariffs and geopolitical tensions – mean that it’s likely that governments will increasingly offer to prop up their national flag carriers when it comes to manufacturing and procurement. France has floated incentives to reshore aerospace production, while India and the UAE are tying purchases to local assembly deals, further complicating the equation for manufacturers that are duty-bound to ensure consistent production standards.

Monocle swings by the invitation-only Strategic Aerospace Seminar on the sidelines of the show, organised by Belgian think tank Premier Cercle. Here, one industry analyst tells us that commercial traffic will continue to grow by up to 5 per cent a year for the foreseeable future. With Nato countries ramping up defence spending, orders for commercial and military aircraft will rise – so building faster and delivering more reliably presents a big opportunity for anyone who can take advantage of this. But, as ever, a single weak link in the supply chain or safety concern can hold up the delivery of an entire aircraft. Nurturing the vast ecosystem of suppliers on which manufacturers rely is crucial, as going it alone is not an option – even for the giants.

Civil aviation

Airbus’s sale of 25 A350-1000s to Riyadh Air, a Saudi airline that hasn’t even flown yet, shows both industry-wide confidence in air travel and continued state support for the sector in the Gulf region. At this year’s event, Qatar Airways has been named the Skytrax World’s Best Airline for the ninth time. Emirates has come fourth this year; it has won the award four times since the inception of the prize in 2001. That’s a lot of visibility and prestige for two countries with a combined population of just 14 million. Saudi Arabia is looking to emulate their success at establishing brands that are admired for the quality of their service.

Meanwhile, low-cost carriers continue to gain ground across the globe (a notable exception is North America), creating a market that’s polarised between premium and budget experiences. “I wouldn’t be surprised if aviation ends up like fashion, dominated by low-cost carriers on one end and luxury brands on the other,” one industry insider tells Monocle at the Aéroports de Paris chalet.

Besides the shifting business models reshaping the carrier landscape, the future of civil aviation largely depends on logistical advances. Airspace is overcrowded, ground staff are overwhelmed and airport logistics are strained, as evidenced by the travel chaos in Europe this summer. Meanwhile, newer, lighter aircraft, such as the Airbus A321 XLR, are capable of bypassing traditional hubs, so airports will need to expand or adapt to increasingly crowded operating conditions. On top of congestion and less predictable weather due to climate change, conflict in the Middle East and Ukraine is restricting the available airspace. It all adds up, leading to lengthy delays, frustrating customers and costing airlines almost €90 per minute.

Alternative fuels

In a year dominated by big guns, the lower profile, less headline-grabbing booths dedicated to clean technology can be easy to overlook. Perhaps that belies a lack of momentum in sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), even though EU mandates, which came into effect in January, impose minimum quotas for the use of sustainable fuels. The atmosphere is sluggish. With that deadline looming and lofty 2050 objectives of carbon neutrality still in place, both availability and the cost of SAFs remain a challenge. SAFs made by recycling food or agricultural and forestry waste can be used as a like-for-like replacement for kerosene (the primary ingredient in jet fuel) while producing up to 80 per cent less carbon emissions. That transition, if it happens, will make a significant dent in the aviation industry’s 2.5 per cent share of global emissions.

Production of SAFs doubled between 2023 and 2024 and is expected to double again by the end of 2025 but the International Air Transport Association has dubbed global progress in replacing fossil fuels as “disappointingly slow”. At fault is the continued abundance of fossil-fuel subsidies, as well as worldwide backtracking on sustainability goals, led by a shift in US policy.

With airline profit margins already razor-thin, few want to spend extra cash on greener fuel without government support. Partnerships between the public and private sector will be crucial in the SAF transition. Given the current economic and geopolitical headwinds, this doesn’t seem likely to be a top priority in a world of conflicts and tariffs.

Kevin Noertker, co-founder of Ampaire, isn’t making promises about net-zero moonshots. He’s starting small, with a combustion engine conversion that turns engines for Cessna Grand Caravans into efficient hybrid propulsion systems that cut fuel use by 50 per cent. “Like the Prius did for cars, they eliminate range anxiety, work with current infrastructure and are available now,” he tells Monocle. The solution that he is developing could eventually encompass passenger-jet engines but clearing regulatory hurdles and convincing the risk-averse to gamble on new technology will take time and effort. As long as SAFs still cost between three to ten times more than conventional fuel, it’ll remain a matter of baby steps where giant leaps are needed.

Space

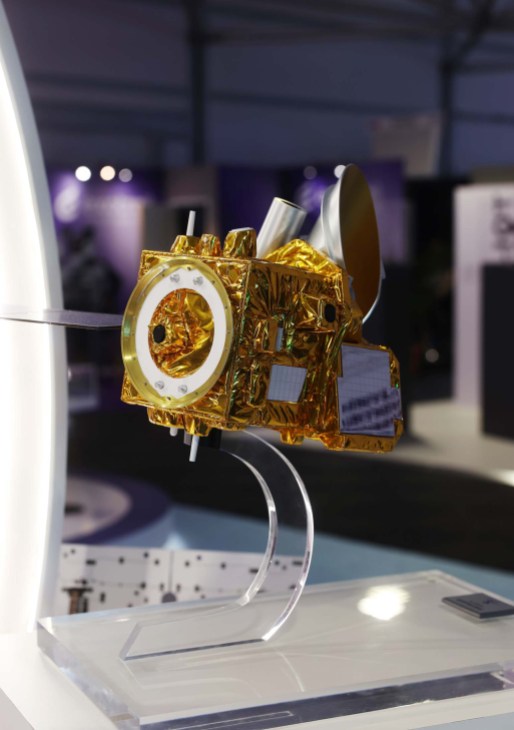

While an F-35 roars overhead and commercial- aircraft deals are being struck below, there’s a quieter kind of aerospace ambition at the air show’s space pavilion. Monocle spots France’s prime minister, François Bayrou, making a hushed visit to the ArianeGroupe stand. Government efforts to reach and navigate space are nothing new but the interest in it as a place to do business is. “Satellites used to weigh 10 tonnes and cost $500m [€438m] to launch into orbit,” says Stanislas Maximin, a co-founder of the Reims-based rocket company Latitude. “New small satellites now cost less than €1m, so we’re seeing massive growth in launches.”

According to a recent report by Goldman Sachs, the satellite market could grow from $15bn (€13bn) today to $460bn (€400bn) in the next decade, with 70,000 low-Earth-orbit launches expected in the next five years. Latitude builds rockets for small satellite launches that Maximin promises are the cheapest on the market. “We just need a concrete slab and electricity,” he says. “Everything else – launchpad, rocket, even facilities – we can bring ourselves.”The main target market? Not governments or their armed forces but commercial clients. “It’s all about data,” says Maximin. “How do we understand our planet better? How do we build services that enable us to track containers or detect tanks?”

With generous public funding, home grown engineers and access to a world-class spaceport in French Guyana, France’s space start-ups are well placed. Latitude’s goal is to work up to 50 launches a year but early failures are expected, including at its first rocket launch, scheduled for the end of 2026. “I just hope that we don’t blow up the $4m [€3.5m] launchpad,” says Maximin with a laugh. As satellites become more accessible, space will become a marketplace – bringing with it unglamorous cargo, including regulation, waste-management procedures and maintenance headaches. Such things have yet to bring entrepreneurs back down to Earth and the optimism here is stratospheric.

Imagine boarding your zero-carbon emissions commercial flight of the future. Is it a curvaceous wide-body jet powered by hydrogen fuel cells? A helicopter-like craft with several rotors fuelled by advanced batteries and piloted by a computer? An airship filled with gas, like it’s 1922 once again? It could be any or all of these. Or none. The truth is that very few people have truly grasped what emission-free flying might look like, let alone how to make it commercially viable enough for it to be an alternative to what we have now. What almost everyone agrees on, however, is that it’s vital to figure it out – and soon.

While there are all manner of promising developments and innovations in the sector, with hundreds of companies large and small working on answering this question, one sticky issue remains: the energy density of jet fuel – the amount of energy held in a given volume – is many times greater than just about everything else we can currently come up with. That is, at least among fuels we can hope to produce and deliver to aircraft, store and use safely. So far there have been lots of lofty promises but not much to show for them.

“It’s not around the corner,” says Henrik Littorin, programme manager at electric aviation development project Elis in the north of Sweden, when we ask about when zero-emissions commercial aircraft will be up and flying. “It’s obvious that the industry is struggling. Existing aviation systems and regulations were developed over many, many years and now you have to do that all over again. And you have to make sure that everything is super safe. That’s on top of the challenges of battery technology and sourcing clean energy. When you start developing something new, such as an electric aircraft, when you start to build and develop it, that’s when you really discover the challenges.”

Littorin says that there is still optimism in the industry but it comes with a sense that expectations will need to be managed. This means a revolution for the entire sector, from the aircraft themselves and the infrastructure to the politics and regulatory frameworks. Everything needs to change. That is disruptive, of course, but there are opportunities too. And for any of this to be viable in the kind of time frames being talked about, every stakeholder needs to be working in concert, pursuing the same goals with the kind of efficiency and co-ordination that is rare on the scale that is needed here.

Yet outfits such as Elis are not waiting for all of that to come together. It has partnered with manufacturer ZeroAvia, the airline Braathens, flight school Green Flight Academy and power company Skellefteå Kraft to launch a demonstrator project to not only fly an aircraft powered by hydrogen fuel cells but also showcase that this can be done within an entirely “green” ecosystem. This means producing so-called green hydrogen, transporting it to the airport and storing it, fuelling an aircraft and flying it to another airport and back. The idea is to show that it’s all possible, even if at a small scale for now.

If you want to look at just about every possible technology we might end up with, it makes sense to look at manufacturers such as Airbus, which has gone all in on figuring out the sustainable aircraft of the future. The company knows that this is an existential question, and with its size and resources it can afford to pursue a number of avenues at once, even if some end up as dead ends.

Until recently, the aviation industry has been on a steady path of incremental improvements in efficiency. Manufacturers point to the fact that since 1990, co2 emissions have been reduced by 50 per cent per passenger. This has been achieved by reducing aircraft weight, improving aerodynamics and boosting engine efficiency. However, because the number of flights has continued to grow, total emission figures remain high. “Today, these three parameters are not sufficient,” says Karim Mokaddem, vice-president Airbus Group Hybrid & Electric Strategy. “If we continue like this, we’re pretty sure we won’t reach the 2050 [net-zero] target.We need another parameter in the game – and that’s the fuel.”

Mokaddem explains that there are two ways to do this: either use electrons as the fuel, stored in batteries or hydrogen fuel cells, or use a different form of fuel, which right now means sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) made from non-petroleum feedstocks.

Batteries are comparatively simple, delivering electricity to engines. But they are heavy and their energy density is low. Hydrogen has a high energy density and zero emissions when used as a fuel but it comes with several complications. It can be very energy-intensive to produce and that production process can create emissions. Hydrogen could either be used directly as a fuel to run aircraft engines or in hydrogen fuel cells, which then produce electricity to run the motor.

“For the moment, we don’t know what will be a viable technology in terms of maturity and the ecosystem,” says Mokaddem. “There’s no silver bullet. Speaking as an engineer, what we have today are only problems. Nothing is really working. We have difficulty finding the right electric motor. There’s no battery that can fulfil what we need.” Increasingly, it looks like different technologies might suit different segments of aircraft, so it makes sense to work on multiple avenues to achieve emissions- free flight. For instance, the current battery technology can be used viably on aircraft that have up to nine seats. That’s not a lot of capacity so it ends up being mostly the domain of “urban air mobility” or evtol aircraft (electric vertical take-off and landing).

As a result, manufacturers are turning to hybrid aircraft models for the regional aircraft segment, which can carry 20-plus people. One example is Heart Aerospace, which is developing a 30-seater aircraft capable of flying 400km. Jet fuel-powered turbo generators charge the batteries that power the engines. It has purchase commitments from major airlines such as Air Canada and United, but for the moment, these commitments are mostly a matter of PR. Its first flight isn’t scheduled until 2026 and that date could well slip.

Some remain optimistic about putting an all-electric aircraft into service using existing technology. Cosmic Aerospace is working on the Skylark, a 24-seater electric plane that can fly 1,000km emissions-free thanks to an ultra- efficient wing, a lightweight structure and other refinements. The company hasn’t waited for a breakthrough in battery technology and says that it can have the plane in service for 2029. “Nothing has changed for us,” says its founder, Christopher Chahine, when asked whether the firm has faced setbacks. He believes that battery-powered aircraft have an advantage because of the inefficiencies and potential emissions of power sources.

“Full-system energy efficiency, from generation to usage, is crucial to ensure that the overall energy needs stay within reasonable limits,” he says. “Hydrogen and SAF generation requires many energy conversion steps, each introducing losses and additional costs. This all adds up to an inefficient use of energy overall. Battery-powered electric systems have a much higher energy efficiency, so there is less valuable energy lost between generation and usage. Energy needs directly translate to operating costs and ticket prices. If flying is to remain affordable and accessible for most people, efficient energy usage will be paramount for as long as clean energy isn’t abundantly available.”

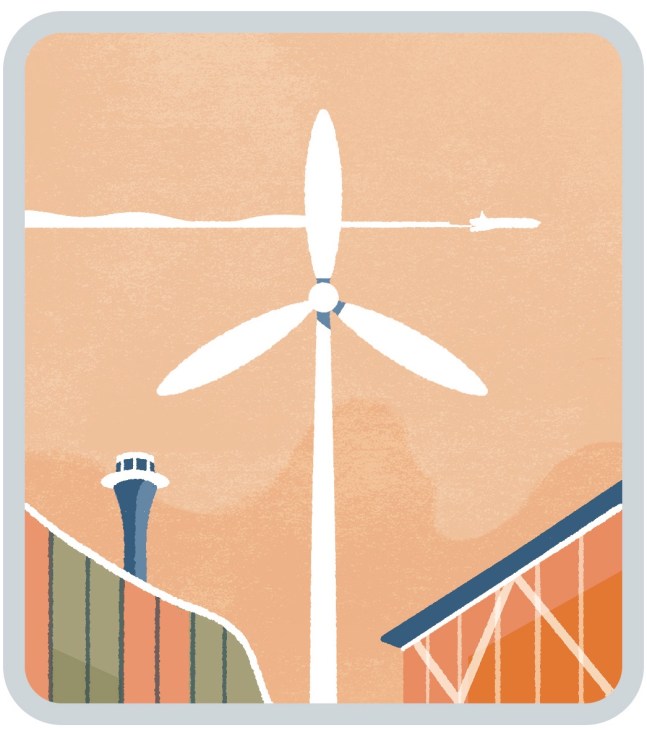

The availability of clean energy is a critical point and is often left out of the discussion. Even once these aircraft are designed and proven to be airworthy and economical, one burning question is where all that clean energy to power them will be sourced. Elan Head, who covers the sector for industry news website The Air Current, points to a recent research paper, which estimated that 9 per cent of the world’s renewable electricity and 30 per cent of “sustainably available biomass” would be required for aviation to meet its net zero targets in 2050.

“Some have proposed that airports should be rethought to become energy farms,” says Head. “If you have an industry that requires massive amounts of renewable energy, then maybe the industry should be responsible for providing some of that energy.”

That leads to another intriguing question: what will the airport of the future look like? Large airports might find that they need to provide multiple fuel sources at the same time, including hydrogen in gas and liquid form, sustainable aviation fuels and megawatt chargers for battery-powered aircraft. How will all these fuels be efficiently delivered to the aircraft that need them? Where will they be generated and stored? The answers are unclear, but these questions will no doubt reshape how we think of building and running airports in the decades to come.

Then there are the wilder ideas for aircraft development. Magpie Aviation is working on a system for enabling longer-range, emissions- free flights without having to invent a more efficient fuel source. According to its vision, a hybrid electric aircraft takes off under its own power and then hooks up to a second or more aircraft with their batteries fully loaded, which tow the passenger aircraft towards its destination. This means that its range can be extended to well beyond 1,500km. The company says that it sees this as the only way to replace commercial flights without advances in technology that we have yet to make.

The general attitude in the industry seems to be that, for now, any and all ideas are welcome. “Working together is the way to get past this,” says Mokaddem. He explains that Airbus is pursuing every possible avenue to see what works, from large hydrogen- fuelled aircraft to small battery-powered demonstrators. And it’s doing this by working not only across the whole Airbus group but also with key players across all transportation industries, from French aerospace giant Safran to automobile company Renault. “For the first time we are not alone,” he says. “Today there are synergies across different transport industries. It took a century for the auto industry to enter into electric mobility. We are willing to do it in less than 20 years.” In the end, Henrik Littorin puts it best. For now, he says, “it’s just really important to get things up in the air”.

Half

Average reduction in co2 emissions per airline passenger since 1990, thanks to improvements in aerodynamics and fuel efficiency.

4.6bn

Annual passenger numbers before the coronavirus pandemic, nearly four times as many as the 1.2 billion in 1990, according to the International Energy Agency.

400km

Maximum predicted range of Heart Aerospace’s electric-hybrid 30-seater plane by its launch in 2026.

9 per cent

Proportion of world’s sustainable energy required by aviation to meet net-zero emissions by 2050.

A third

Approximate amount of the world’s sustainably available biomass that would be needed to power aviation if net-zero is to be reached by 2050.

About the writer:

Stockholm-based Leigh is Monocle’s transport correspondent.

Illustrations by Yo Hosoyamada

Etihad Airways’ first Airbus A321LR enters commercial service today, 1 August, debuting on the Abu Dhabi-Phuket route before expanding to Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Copenhagen, Milan, Paris and Zürich.

The aircraft represents a bold step for the company, being the first single-aisle jet in the world to feature a dedicated first-class cabin. It introduces long-haul features such as lie-flat beds and private suites into shorter-distance markets previously served by more basic cabins. The move is a calculated bet on the future of luxury travel.

Monocle’s transport correspondent Gabriel Leigh joined the Middle Eastern airline on the passenger jet’s delivery flight from Hamburg to Abu Dhabi, and Georgina Godwin on The Globalist to report on the “premium-heavy” onboard atmosphere.

“They’re trying to give premium-level passengers a seamless transition from long-haul widebody flights to these new routes, where they still get lie-flat beds, privacy – even closing doors in first class,” he says. “It’s a very beautiful aeroplane on board.”

The A321LR, which is part of the A320neo family, is configured with two private First Suites offering wireless charging, Bluetooth pairing and space for a guest. Business class is comprised of 14 herringbone seats that convert into lie-flat beds – a layout usually reserved for the likes of the A380.

The airliner’s long-range capability allows companies to operate longer and fly less conventional routes that wouldn’t have been practical before. “Airlines such as Etihad can experiment a bit,” says Leigh. “They couldn’t fly to many places – say Krabi, Medan or Phnom Penh – with wide-bodies, but this aircraft lets them reach those destinations and see how the routes perform.”

Aviation experts agree. Paul Charles, CEO of the PC Agency and former director at Virgin Atlantic, says the move signals a shift in how high-end travel is delivered, and a big step ahead of competitors. “Etihad is saying, ‘This is the new battleground for us,’ and they’re determined to make it a success, especially with rising competition from new carriers such as Riyadh Air. The food quality is superior too.”

The new jet arrives amid the air carrier’s growth spurt, with 27 new routes launched or announced in 2025 alone.

The UAE airline’s gamble is clear: that premium passengers will pay for comfort, even on mid-length flights. “Most travellers don’t even think about aircraft type,” says Leigh. “If the seat, space and privacy feel the same, Etihad may convince them that single-aisle luxury can match long-haul expectations.”

If customers are willing to pay more for a better experience, even on shorter routes, Etihad is making sure that it meets the mark. Will other airlines rise to the pressure and catch up?

Listen to the full report from 51:10, below:

About 15 years ago, Czech aircraft designer Milan Bristela saw a significant jump in the maximum speed at which small planes could travel. “But when I saw the pilots getting out of these aircraft, they would be complaining about back pain,” he says. “We realised that there was no plane on the market that was providing a speedy and comfortable ride. So we decided to focus on the ergonomics and spaciousness of the cockpit to make people feel more relaxed and safe.”

Leaving his corporate job in 2007, Milan teamed up with his son, Martin, and went on to found their own business, Bristell, to address this gap in the market. “At first, the idea was really just to build a few aeroplanes a year,” Martin tells Monocle. “We thought that it would basically be about playing with this idea – and that it would be our job, yes, but also our hobby.”

But what began as a passion project in a small, rented workshop space has become Bristell, one of the world’s premium lightweight aircraft manufacturers. Employing about 140 engineers, designers and mechanics, it now has an impressive production floor in a 10,000 sq m factory in southeastern Czechia where aircraft are built from scratch.

The company produces more than 110 two-seater planes composed of lightweight aluminium per year. The aircraft pass through a complex process of welding and assembling before being fitted with engines in a cavernous hangar. The finished planes are dispatched to customers in countries from the US to Germany, for training pilots or as private aircraft for customers looking to crisscross long distances with ease.

“Every day, when I come into work, I take a walk through the factory to see what everyone is up to,” Milan tells Monocle. “My son and I developed every plane that is being constructed here as a prototype. We know exactly how long it takes to put them together because we build all of the models first with our own hands.”

Like his father, Martin is closely involved in the day-to-day running of the company. “I make my way through this place once or twice a day too,” he says. “It means we can keep our eye on the quality and make improvements as quickly as possible.”

Creativity and ingenious engineering comes naturally to the duo. “I built my first tractor when I was in secondary school,” says Milan. “In communist-era Czechia, you would have to wait years to earn enough money to buy things such as a tractor but we needed them to grow food. So I decided to build one myself. It was a metre wide, two metres long and had a car engine and gearbox. It allowed me to help with farming our land.”

For both father and son, keeping aviation manufacturing based in Czechia is also a matter of national pride. “Our country has a strong tradition when it comes to aircraft manufacturing and design,” says Martin. “The airfield that we operate out of is owned by aircraft manufacturer Let, which was founded just before the Second World War. About 40km away, we have Zlin, which is famous around the world for how well its planes perform in aerobatic competitions.”

“Our mentality is all about creativity,” Milan says of his countrymen and women. “It allows us to develop new things quickly.”

Based between the Mexican capital and Oaxaca City, the Fernández clan – best known for transportation business Traylfer – is developing and building a “Made in Mexico” aircraft in a country not well known for its plane-making prowess. The family’s Oaxaca Aerospace has built a series of prototypes for its diminutive Pegasus jet, with its distinctive “canard” formation (small wings at the front) and large ducted propeller at the back. The impressive PE-210A was followed by this year’s P-400T, unveiled at the Famex aerospace fair in Mexico City.

Rodrigo Fernández is the family business’s second-generation leader. The general manager says that Oaxaca Aerospace, which foresees military and civilian applications for its planes, is now ready for takeoff. The next step is to conduct further flight testing, with the goal of eventually converting the family factory that lies about a 20-minute drive from Oaxaca City into a production line for a full-fledged international plane developer.

How did Oaxaca Aerospace come about?

We’re a family business and my father is its president. For many years we specialised in fabricating trailers for transporting cargo. We have been making them for 40 years. My father has always loved aviation and has been up in those small, stripped-back Cessna planes that don’t have much technology. At some point, he wondered, “Why can’t we make a plane like this in Mexico?” and decided to do it. He began gathering together engineers and then we made our first drawings – that was in 2011. We had our first prototype by 2015 and began testing.

Was it difficult to develop and build an aeroplane in Mexico?

Yes, because there isn’t much of an industry here when it comes to making aircraft. Mexico has focused on the maintenance and manufacturing of parts, rather than on the design side. So it has been hard to find experts in aeronautics. We had to look overseas to universities and to retired people to help us keep the project moving forward. We do our wind-tunnel testing in Madrid, for example.

Have you identified a market for the Pegasus?

Our market is principally made up of emerging countries. We’re not about to take on advanced countries that have aircraft that are much more complex and sophisticated. Our proposal is more about military observation and safety missions, pilot training and things like these. There are a lot of countries in Latin America, as well as in Asia and elsewhere, that require this type of aircraft for these types of missions. If we can build a plane that has a low cost for maintenance and operation, it will be very attractive.

How far are you planning to go?

The dream is to eventually sell our planes across the globe and for the company to grow. We would also like to sell executive planes, such as a seven-seater.

aeronavespegasus.com

Steps to success

1. Believe in what you do: Passion can take you a long way. In this case, a family’s love of aviation trumped the lack of an established industry.

2. Find the right people: Don’t be afraid to look abroad. Gather experts around you wherever they are in the world.

3. Know your market: Oaxaca Aerospace knows that its offering can’t compete with advanced jets so it is creating its own niche.

Read more from Monocle’s 2025 Mexico Survey:

- Inside Mexico’s creative gold rush: four high-growth industries to watch

- Three game-changing developments about to transform Mexico City

- Entrepreneurs to watch: the forward-thinkers making new paths in Mexican industries

- Eight ideas for Mexican businesses that are ripe for the taking

- Meet the self-starters behind the clever hospitality boom in Oaxaca City

- The entrepreneurial trailblazers revitalising Guadalajara’s art scene