In search of Australia’s natural bounty: A guide to the Grand Pacific Drive

Heading south from the Sydney sprawl, the nation’s seemliest highway wends its way along a rugged coast to reveal lesser-seen treasures.

Flying to Australia from almost anywhere can be daunting: it’s about 20 hours from Europe, 13 from the US and 10 from northern Asia. But the journey has its rewards. One of the world’s most diverse countries, it is home to coral reefs, expansive woodlands, red deserts, snowcapped mountains and lush rainforests – and some interesting inhabitants.

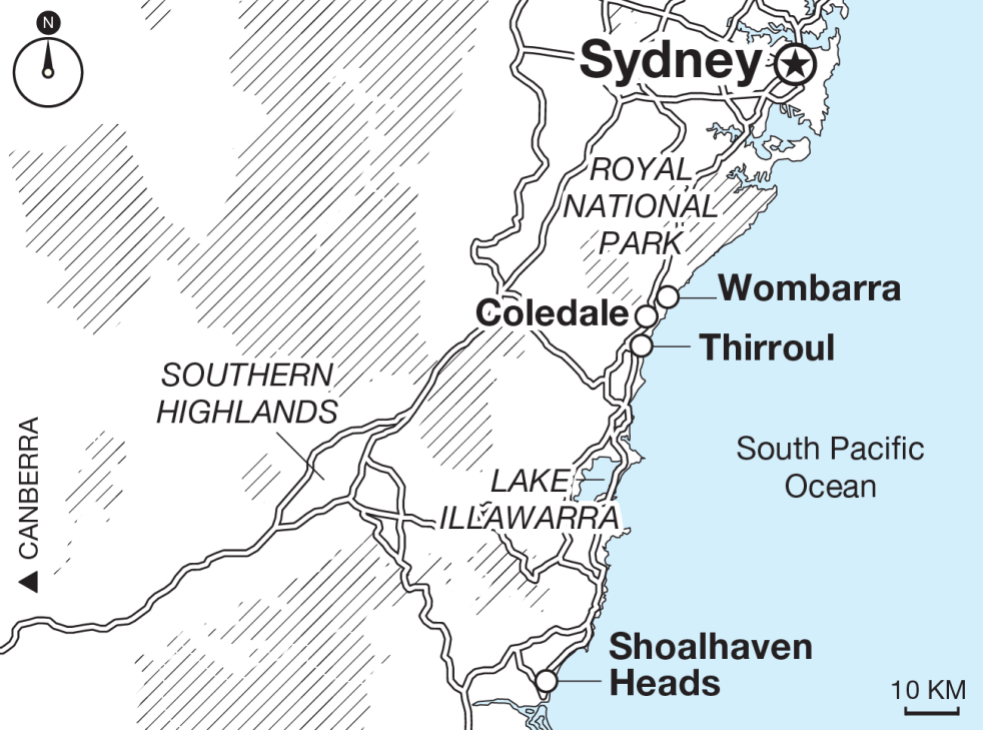

The continent’s scale makes experiencing it all a challenge. South of Sydney, however, there’s an opportunity to glimpse much of what Australia has to offer in a single, swift journey. Cutting through Illawarra, Shoalhaven and the Southern Highlands, you’ll spy dramatic coastlines, peaceful estuaries and rugged mountain ranges.

The richness of these landscapes is reflected in the stories of the Aboriginal people – the Dharawal, Yuin and Gundungurra – who long lived off the abundance of food around the lakes, waterways and ocean. Later, European settlers used the same natural bounty to establish powerful industries, from coal and timber.

This unique combination of geographies is best explored by hitting the open road – namely the Grand Pacific Drive, which starts in Sydney and tracks south. Combined with a stretch of the Hume Highway, it makes a neat 500km loop, weaving through small country towns and beachside cities, where family-run shops and independent wineries dot the landscape.

Sydney to Illawarra

The six-lane road that takes drivers from Sydney onto the Grand Pacific Drive starts by cutting through the Royal National Park at the New South Wales capital’s southern edge. Here, the road dips and walls of eucalyptus trees rise, signalling your departure from the city. A sign directs you onto the 140km coastal route: a brown background with a landscape stylised with streaks of blue (representing the ocean), yellow (the coast) and green (nature). It’s a fairly accurate representation of the Illawarra, a flattish strip tucked between the escarpment and ocean.

Here, suburbs and villages such as Wombarra, Coledale and Thirroul punctuate the coast leading to the regional centre of Wollongong. Pubs sit on steep cliffs beside mass-made post-Second World War Fibrolite (or “Fibro”) beach houses, from which rolling surf breaks are visible. In Austinmer, large swimming pools hewn from coastal rock are flanked by Norfolk pine trees; in Coalcliff, another rock pool offers unrivalled views of the escarpment.

Access to these communities is via the Sea Cliff Bridge and the adjoining Lawrence Hargrave Drive Bridge – two roads that cling to the rock face. The views are well known, even to Aussies who have never visited, as the backdrop to seemingly every car advert on TV. Make a pit stop at any café and you immediately feel that, though we are within 75km of Sydney, there’s a much stronger sense of community here. “How are you doing?” calls one person to another as Monocle passes the Moore Street General Store. “Good,” comes the reply. “Is it your birthday? I drove past and saw you carrying a big bouquet of flowers.”

It’s the sort of atmosphere that pulled designer Orlando Hayes back to the region after a stint in Sydney. “You couldn’t pay me to return to the city,” says Hayes. The appeal, he says, is the laidback lifestyle – but this disguises the reality that, for much of the early 20th century, these were hard-working blue-collar towns. For decades, the local economy was driven by the Australian Iron and Steel plant, which opened in 1928 and was powered by coal mined in the region. Efforts have since been made to diversify. A state government plan has identified precincts for housing and job growth, with money being pumped into tourism, education, business and healthcare.

Shoalhaven

A little further south, our next stop is Shoalhaven, 150km from Sydney. We spend the night at Paperbark Camp, which offers pared-back, tent-like accommodation and an excellent dinner at Gunyah (an Aboriginal word meaning “meeting place”). The restaurant is designed by Sydney architects Nettleton Tribe and is built high off the ground to take advantage of the sea breeze and the rustle of leaves amid the treetops.

Shoalhaven is very different to Illawarra: the land is flat, the population is sparser and the pace of life slower, with the coastal portion of the Grand Pacific Drive terminating here and cutting inland at the town of Shoalhaven Heads. The beaches are a little wilder and so is the range of activities on offer. Monocle stops at Summercloud Bay in Booderee National Park and chats with a surfer. People also fish off the rocks here. “Nothing’s biting,” one of them tells Monocle. That’s perhaps a good thing for the surfer, as white sharks often prowl these waters.

“It’s a stunning bay, lined by sandstone cliffs, with white-sand beaches and more than 60 dive sites,” says Lara Boag, who runs the diving outfit Woebegone in Shoalhaven’s Jervis Bay with her husband, Dylan. When we visit, they’re getting ready to lead a snorkelling excursion and making repairs to their boat in preparation for the summer crowds. “Throughout the year we have these major seasons with different marine life,” says Boag. “So it’s never the same. We have whales, seals and sharks at various times of the year.”

In addition to the coastline, Shoalhaven also has an estuarine landscape created by its eponymous river, which supplies some of the region’s best seafood. It’s reflected at the mouth of the Crookhaven river at Greenwell Point, where you’ll find several oyster farms. Perhaps the best known is the small, family-owned Jim Wild’s, which was established in 1979. Visitors are greeted with an enormous fibreglass oyster shell. The farm is named after the national champion shucker, whose daughter Sally McLean has followed in his footsteps and has won the Australian women’s title five times (most recently in 2025).

Jim Wild’s offers Sydney rock and Pacific varieties, depending on the season, and visitors can eat the fresh oysters on the waterfront deck. “We have pristine waters with the right conditions for oysters, so people come here for that,” says McLean, who, having moved away after finishing school, returned to Greenwell Point in 2012 to run the business. “But they also come just to say, ‘G’day.’”

The area’s cultural clout is equally strong. Bundanon art museum is one of Australia’s nine National Collecting Institutions, responsible for preserving and sharing the country’s heritage, and the only regional outfit. It was established in 1993 after artist couple Arthur and Yvonne Boyd gifted their property in Shoalhaven to the Australian people. “In the 1970s they came to see friends who lived in the area and they were just blown away by the landscape,” says the museum’s CEO, Rachel Kent. “So they said to their friends, ‘If any land comes up for sale, tell us.’”

Eventually, a plot became available – and then another. The Boyds soon assembled a patchwork of properties. Kent’s responsibility now is to maintain both the creative legacy and the environment. “One of the things that Arthur always said is, ‘No one man can own a landscape,’” she says. “It was this idea that Bundanon was not theirs for keeping but rather that it should be shared with everyone.”

In addition to presenting exhibitions and housing art, the organisation runs artist retreats, as well as educational and cultural programmes with facilities spread over two sites. The first is at Arthur’s former homestead and studio, while the other campus, which sits at a bend in the Shoalhaven river, has a 32-bed dormitory completed in 1999 to the design of a team including Pritzker-winning Australian architect Glenn Murcutt.

This is complemented by a subterranean art museum and collections store, partially buried in the landscape to protect the works from fire and flood. There’s also The Bridge, which houses the creative learning centre for schools, a visitor information centre, accommodation and a café. “These buildings are about being in conversation with the landscape,” says Kent of the structures, which were completed in 2022 to the design of Melbourne-based architect Kerstin Thompson.

The Southern Highlands to Sydney

A straight shot inland from the Shoalhaven is the Southern Highlands region. To reach it, you can take any number of routes that cut through agricultural landscapes and Morton National Park. Monocle passes Fitzroy Falls, an 81-metre drop accessed via a gentle bushwalk. Nearby is Kangaroo Valley, which is known for its lush, green landscapes, rolling hills and charming homesteads.

Its flagship structure is Hampden Bridge. Built in 1898, it’s Australia’s last surviving wooden suspension bridge, with its gothic sandstone towers offering picturesque views of the Kangaroo river – a superb setting for spontaneous swims. That’s where Monocle meets Ellen Green and Tim Jayatilaka. “It’s the most magical place on earth,” says Green, whose family has long holidayed in the area. “The community makes it special. Even just meeting people down at the pub.”

This bonhomie comes to the fore at Osborn House. “There’s a strong sense of community in the Southern Highlands,” says the hotel’s general manager, Caitlin Walter. “Visit any shop or restaurant and you’ll feel as though you were being welcomed into someone’s home.” Established in 1892, it features 15 unique guestrooms and a cluster of 12 cabins, with views of Morton National Park. “It’s why everyone should visit the region, even just for a few days. If you want to see Australia, this is the best place to come. The bush and countryside are amazing.”

While it’s tempting to stay on the grounds of Osborn House – which has a century-old botanical garden, a 25-metre swimming pool, steam room, sauna and spa facilities – it’s worth paying a visit to the regional hub of Bowral, where you can browse a smattering of antique shops and smaller galleries. It’s a polished counterpoint to the more bohemian cafés and businesses that can be found in Illawarra – proof that the region’s retail, hospitality and culture are as varied as the landscapes.

This is something that’s further illustrated by one last major landscape shift that’s visible on the return leg to Sydney. Visitors can pass through the remnant of a rainforest that once stretched across the region. Stopping off at Budderoo National Park, you can find walks that snake beneath the verdant canopy. By the time you reach Sydney’s outskirts, the 500km loop comes full circle with the rarest of Australian delights: diversity delivered without the tyranny of distance.

Where to stay, eat and drink along Australia’s Grand Pacific Drive

Stay

Paperbark Camp and Gunyah

Luxury tented stays nestled in bushland, with open-air baths and elevated dining.

paperbarkcamp.com.au

Stay

Osborn House

A restored 1892 guesthouse with spa facilities and excellent food, overlooking Morton National Park.

osbornhouse.com.au

Visit

Bundanon art museum

A gallery celebrating Arthur Boyd’s legacy on his former estate.

bundanon.com.au

Visit

Ngununggula

The place to come for rotating exhibitions with a focus on Aboriginal art.

ngununggula.com

Eat

Rosie’s Fish and Chips

Impeccable seafood, locally caught.

rosiesfishandchips.com.au

Eat

Blak Cede

Indigenous flavours run through this café that’s known for its outstanding loaves.

blakcede.com.au

Drink

Sutton Forest Inn

Local wines, beers and meals in cosy interiors or sprawling gardens.

suttonforestinn.com.au

Drink

Finbox

Get your caffeine fix – and surfboards – at this coastal coffee outpost.

finbox.com.au

Read next: How to explore Australia’s Great Southern