How Sofia’s comeback is shaping a new cultural identity for Bulgaria

Communism’s shadow has been slow to fade in Sofia but today a new generation of young hospitality players is welcoming visitors to a city full of opportunity and Old World charm.

Most of us have – at least once – imagined our hometown or another city as a person. What are they like? Old or young? Male or female? Impeccably groomed and besuited or scruffy and bohemian? Do they wake up early and jog or dance until dawn? Or all of the above?

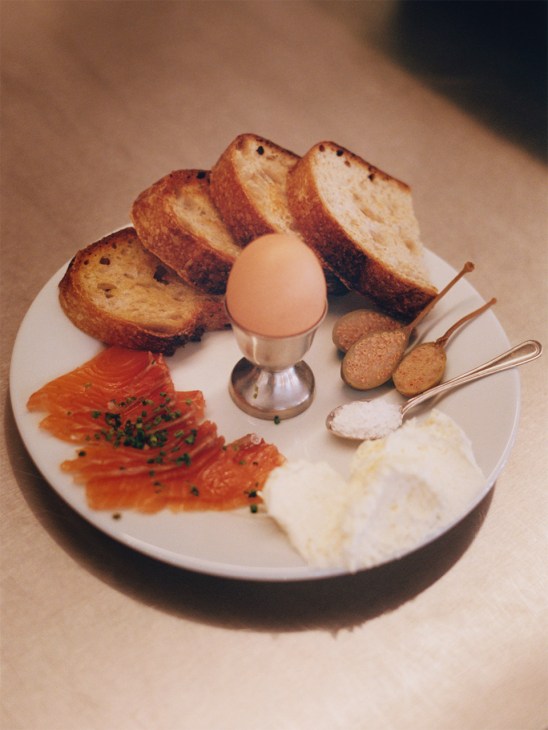

The game is irresistible in a place such as Sofia. For a start, the character’s name is already chosen. Some residents refer to Bulgaria’s capital as “she” or “her” in casual conversation. When Monocle sits down with Kristin Radoilova for some smoked salmon and omelette at her restaurant, Sabale, she has a few thoughts on the matter. “If Sofia were a person, she would be dressed in an aristocratic coat and own a few rentals around town,” says Radoilova. “She has seen a lot – and suffered a lot – but has managed to stay sweet.”

The tough times include years of Communist rule, which lasted from the 1940s to the fall of the Berlin Wall. But Sofia doesn’t bear many scars: walk down its stately streets and you’re more likely to be reminded of Vienna or Munich than a bleak post-Soviet city. The skyline is still punctuated by the spires and onion-shaped domes of the Orthodox churches wedged between art nouveau palaces and well-tended theatres. At first glance, the impression is one of turn-of-the-century splendour.

But political and social turmoil can lurk behind even the most scenic façades. Bulgaria has seen a lot of it since the end of the Soviet era. Most people we speak to remember the 1990s transition to democracy as an Eastern European version of the Wild West and a time of mass exodus from the country. The long fight against corruption continues amid fast-changing governments but if the city has reasons to be optimistic, it’s thanks to people such as Radoilova who are taking matters into their own hands.

Radoilova quit a corporate job in advertising three years ago to start a bakery specialising in cinnamon rolls. She did so without any prior experience; there was no one else in the city making the kind of sweet treats that she loved. “A year later I thought, ‘What else do we need in Sofia?’” she says. “The answer was a breakfast place serving the best ingredients in a minimalist interior.”

The result is Sabale, set in a former tea warehouse. Radoilova sources most of the produce used in its breakfast classics from independent Bulgarian farms. Rather than dwell on the drawbacks of being in the country, she likes to focus on the advantages. “It’s very easy to make your dreams come true here,” she says. “If I wanted to open a spot like this in Amsterdam or Copenhagen, there would be hundreds of similar places. In Sofia, you can be the first. It feels almost like a blank slate: you can do whatever you want.”

That’s especially true of Sabale’s surroundings – the former Jewish quarter, just north of the cumulus-shaped St Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. Residents have taken to referring to it simply as the “Kvartal” (Bulgarian for “the neighbourhood”). Here, the buildings are a little shorter and scruffier than in other parts of Sofia, and the streets are leafier. It’s a place that lends itself to strolling.

Yordan Zhechev is behind some of the Kvartal’s most appealing outposts and, though he denies it, is at least partly responsible for its upward trajectory. “I just don’t like saying no to stuff,” he tells Monocle from inside ZH Jazz Room, which was his first outpost in the area. “I like doing things that I have never done before and seeing what happens.” Using funds raised during his previous career in advertising, he launched the listening room and café in 2020. It quickly became popular and today we’re lucky to find room on its velvet armchairs. A Miles Davis record plays as Zhechev pours us a salep, a sweet Turkish drink made from orchid root and milk. He offers us some chocolate truffles by La Fève, a Bulgarian brand in which he has invested (he’s also, it turns out, a partner at Sabale).

As we talk, the list of Zhechev’s neighbourhood projects seems to grow and grow. He has helped to open nearby bakery &Bread (the happy consequence of the founders’ lockdown passion for sourdough) and the Sezon grocery shop opposite. His newest location is Mahala, an airy bookshop that he created with translator Maria Zlateva in 2023. A sense of spontaneity is what he appreciates about this neighbourhood and Sofia as a whole: though a festival has been launched in the Kvartal to celebrate all of its businesses, the area still feels as though it eschews excessive planning. “What I love about this place is that you can call anyone at any time and ask, ‘Do you want to do this?’” he says. “And the chances are that they’ll say yes.”

According to Zlateva, Mahala was born almost on a whim. “One of us said, ‘Why don’t we start a bookshop?’ and that’s how it started, without thinking too much about it,” she says. On the shelves are translated books by Bulgarian authors and English-language titles, hinting at a growing community of expats in Sofia.

Dmitrii Efanov, who we meet as he walks his dog, is one such newcomer. The Russian graphic designer left St Petersburg when the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in 2022 and is happy with his choice. “I think that the coming decade will be that of the Balkans,” he says. “People will be happy not to be in Western Europe. It’s very chill and super-safe here.”

A balance between busyness and calm – the cultural calendar of a European capital but the size of a second city at about 1.3 million inhabitants – is the reason why many creatives are staying or returning here, rather than seeking higher wages further west. Since 2020, the annual number of Bulgarian returnees has surpassed that of those leaving. Fashion consultant, buyer, designer and curator Julian Daynov is one of them: though he still keeps a foot in Berlin and Athens, he fell back in love with his home city and is now an evangelist for it. “I’m from a generation of Bulgarians who thought that they had to leave the country as soon as they were of age to build their own life,” he says, his long, dark hair slicked back in a bun.

“We grew up with the scars of Communist Bulgaria, where we were limited in our choices and visions. We knew that there was a big world beyond the borders and wanted to see it.” Daynov left in 2003 and lived in Germany, Switzerland, the UK, the US, Denmark and Greece, working for companies from Saks Fifth Avenue to Prada, before he started to come back on production trips to Bulgarian factories. “I saw many of my peers who had lived abroad returning, building their businesses and families here.”

For Daynov, Sofia’s appeal lies in the fact that it’s “sort of an underdog city”. “That’s what makes a place interesting: when there’s so much that’s still undiscovered and you have the possibility to shape it. It’s liberating to experiment.” There’s also an element of delayed recognition. “People have a lot of pride about the country, its history and nature. It’s paired with the idea of turning this into something cooler, greater and bigger. It’s very Bulgarian to want to prove something to the world. Being suppressed for years, living behind the Iron Curtain, we didn’t have an equal start but we can make it through.”

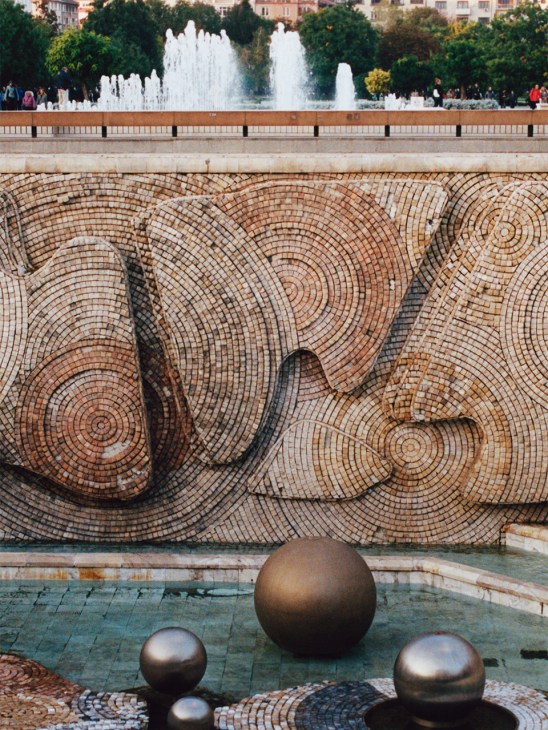

The Communist years remain a big part of Bulgaria’s cultural conversation, says Dimitrina Ivanova, the culture editor of Dnevnik newspaper. “In the Balkans, we have a specific relationship with the past. There’s a darkness in us that’s reflected in Bulgarian movies and literature.” Tonight, she’s rushing to catch screenings that are part of the Cinelibri film festival in the National Palace of Culture, a hulking reminder of the Soviet years. “Last weekend we had the Sofia Art Fair, with contemporary galleries from all over the world,” she says. “We had a big jazz festival in the summer – totally free. Sofia is a really cosy town but there’s lots happening at the same time.”

As for a glimpse of the future, a stay at Dot Sofia is a good way to understand where the city’s high-end hospitality scene is heading. Clad in russet-hued Corten steel punctured by tiny dots, the hotel was designed by Bulgarian firm I/O and sits like a spaceship in the oldest part of the city – a long-neglected area west of the Kvartal, close to the Women’s Market. Its owner, Pancho Georgiev, is a management consultant who was born in Bulgaria, grew up in Switzerland and is now based in Dubai. He comes back to his home country almost every month and admits that he took a punt on the site.

“My Bulgarian friends asked me, ‘Are you crazy?’” he says over a glass of Bulgarian dimyat wine at Komat, the hotel’s restaurant, which is run by returnee chef Todor Grublev. Georgiev’s desire to create the kind of place that he enjoys elsewhere is coupled with a sense of responsibility towards his hometown. “I thought, why not create a place where we can host people and contribute something to the city at the same time?”

Gallerist Vesselina Sarieva joined the project to look after two exhibitions per year while directing its broader programme. Sarieva has made it her mission to elevate her country’s art scene. Inspired by a visit to Berlin and its Long Night of Museums, she created a similar festival in her hometown of Plovdiv, started a foundation to educate the public on national art history and presented Bulgarian artists at international fairs.

“Development doesn’t come if you’re the only one who develops; it comes when everyone around you does too,” she says, her features framed by the boldest of micro-fringes and a sharp bob. Disappointed by the institutional cultural system, she had already moved to Sofia and started a contemporary art gallery here when Georgiev came calling. “He told me that a new age was coming,” she says. “Pancho and this building helped me to believe that we can do things. Now enthusiastic Bulgarians are coming back and they ask me, ‘What have you been doing all these years?’ And I say, ‘I was here, waiting for you to return.’ I was waiting for this to happen.”

Where to eat, drink, shop and visit in Sofia

Eat

Sabale

This laid-back restaurant at the edge of the Kvartal is the best spot to start your day in town. The menu is all Scandi-inspired breakfast classics: order the house-cured salmon platter with pickles or the omelette. Georgi Benkovski 11

Eat

Cosmos

Fine-dining restaurant Cosmos pushes the boundaries of what’s considered “local”. Working with small Bulgarian producers, it shows “traditional recipes twisted to our cosmic view”, says its executive chef, Vladislav Penov. cosmosbg.com

Drink

ZH Jazz Room

The first of Yordan Zhechev’s projects in the Kvartal, this listening bar is best at night. In winter a fireplace adds to the charm; once a month, there are live music sessions – and the cocktails are excellent. zhsofia.com

Drink

Rooftop Bar

The view of St Alexander Nevsky Cathedral from this bar at the top of Sense Hotel might be the best in the city. It serves an inventive drinks menu. sensehotel.com

Shop

Mahala

The selection of books in this handsome space is compact but smart. Most titles are international; there are also highlights of contemporary Bulgarian literature. It hosts events, book-club discussions and open-mic nights. mahala.bg

Shop

All-u-re

Across two locations, All-u-re’s selections span Alaïa and Marni to Saint Laurent, jewellery from Bulgarian-born designer Milko Boyarov and photographs by Elina Kechicheva. all-u-re.com

Visit

National Palace of Culture

Opened in 1981, this building is the most striking architectural reminder of Sofia’s Soviet past. Its auditorium hosts concerts, plays and festivals. ndk.bg

Visit

Plus 359 Gallery

This contemporary gallery hosts site-specific performances and installations by artists from Bulgaria and beyond, fostering the emerging art scene. plus359gallery.com

Stay

Dot Sofia

The building’s unusual perforated Corten façade hints at the impressive architectural quality of the structure within: sleek, minimalist and clad in concrete but warmed by wooden details. dotsofia.com