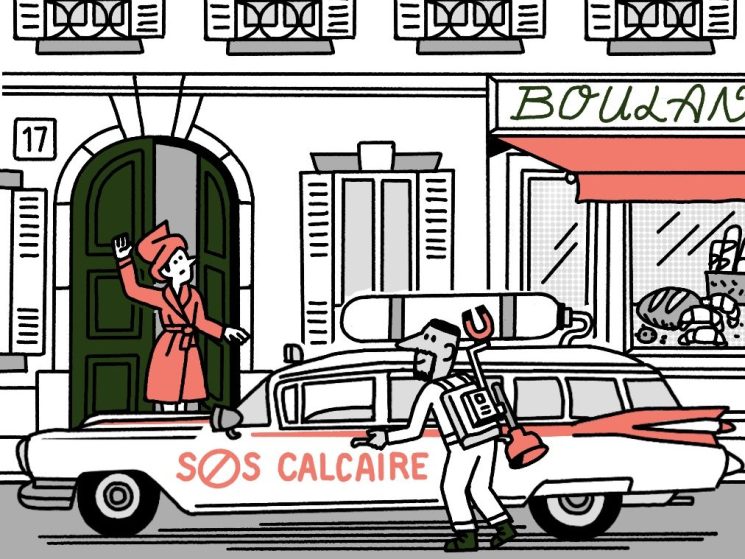

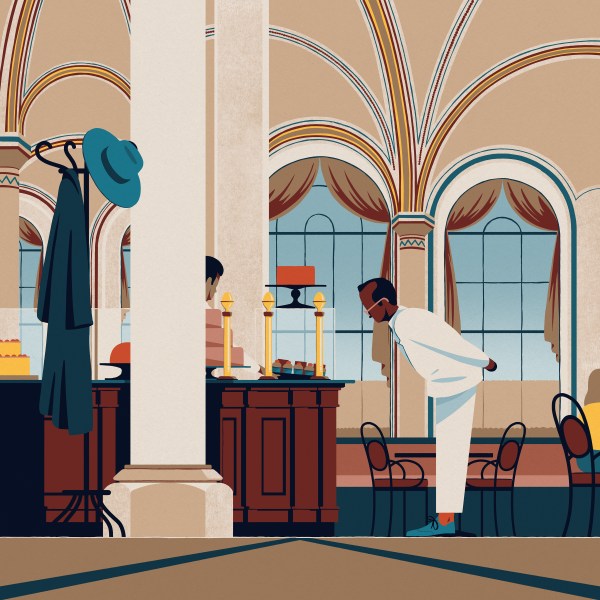

‘In turbulent times, the bistro is a tonic.’ Can Unesco save this famed Paris institution?

France’s bistros are on the decline but a new generation of young restaurateurs in the capital is proving that the appeal of the bistro remains in its dependability.

DESIGN

see all

How Maison Kitsuné’s Gildas Loaëc keeps his second home flourishing through the year

When French entrepreneur Gildas Loaëc commissioned a residence in Bali, he intended it to serve as a second home that he would occupy for two weeks every two months. But once it was completed,…

FASHION

see all

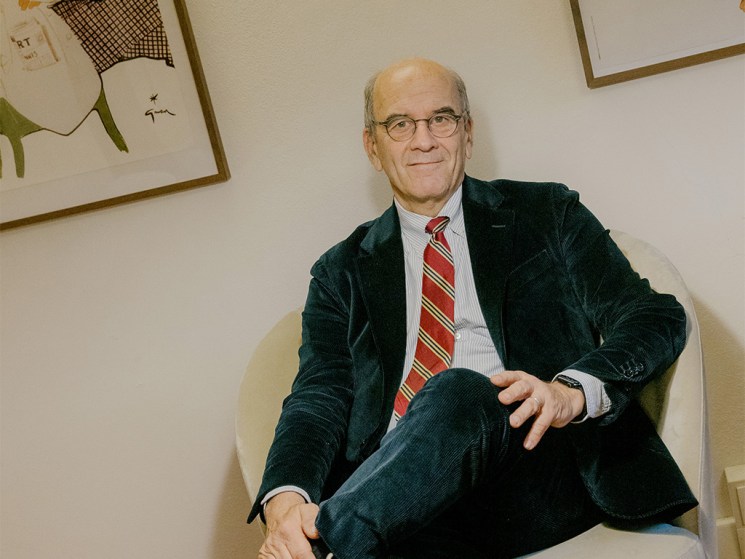

‘I’ve never bought anything because it’s fashionable’ – Pitti CEO on dressing the part

Presiding over Pitti Immagine Uomo since 1995 is the affable Raffaello Napoleone. As CEO, he oversees the trade fair’s organisation and ensures its continuing relevance in Italy and beyond. He tells us more about…

TRAVEL

see all

Discovering Gora Kadan Fuji, a new luxury Ryokan built to frame Mount Fuji

Fujisan’s iconic outline is familiar to all – but a stay at the new Gora Kadan Fuji hotel offers beguiling views of Japan’s highest peak that will make you see it anew.

EVENTS

The Monocle Pop-up Shop, St Moritz – 4 December 2025 –– 31 March 2026

Drop by for a warming coffee or hot chocolate and explore our edit of Monocle products and reads for the colder months.