“The sun will come out again,” says costume designer Catherine Martin in a theatrical voice, as the brief spell of summer rain subsides and the sun begins to emerge through the tall windows of her suite at the Hotel Martinez in Cannes.

The French-Australian Oscar-winning designer has spent much of her life by the beach and seems to embody the optimistic, carefree spirit of the season. “During summer, you’re costuming yourself for what you hope will happen: to find yourself in a nautical place or inside a Raoul Dufy painting,” says the designer, who is dressed in a striped marinière Miu Miu tank top and a navy blazer thrown over her shoulders. “You want to feel connected to the seaside and the warm air. Prints become much more desirable at this time of year – a dress that slips over a swimsuit, a reclaimed-cashmere jumper that you can throw on when it gets chilly at night and beach clogs that you slide on after walking on the sand. It’s all about the feeling of barefoot luxury: simple and optimistic.”

It’s no surprise that Martin can instantly paint a picture of the idyllic summer wardrobe, imagining the characters and the worlds that they inhabit. She has been designing costumes for films such as Romeo and Juliet, The Great Gatsby, Moulin Rouge and Elvis for nearly three decades.

This summer, however, she has been spending time outside the costume department, conceiving her very first off-screen capsule collection with Miu Miu (its founder, Miuccia Prada, is a longtime friend and collaborator). She built the new range, which features deadstock fabrics, around an “imaginarium”: a visual diary of a trip to the south of France in the 1920s and 1930s, complete with archival images, collages and written artefacts. The result is a collection of sharp rowing blazers, featherlight slip dresses, cotton beach trousers and striped tops that will have you embracing nautical dress codes – and maybe even planning a trip to the French Riviera. It launched exclusively at the label’s newly-refurbished London flagship on New Bond Street, with a worldwide launch set to follow on June 21. A short film accompanying the collection’s launch, dubbed Le Grand Envie, marks Martin’s directorial debut: her partner, the director Baz Luhrmann, encouraged her to take the leap. It is set in a southern château and captures the hedonism associated with the region.

“What is it about the south of France?” asks Martin. “I understand why people have been coming here since the 19th century – or even earlier. There’s a softness to the light and the landscape is beautiful. When I first came to Cannes in the 1990s, it was the place to watch and to be seen. It’s different today but there’s still [an appeal], whether you are just sitting at a café sipping an Aperol spritz or at one of the exclusive beach clubs on the Croisette.”

References to the 1920s also encourage the wearer to look back and reflect – something that the slower months of summer call for. “This was a really interesting period: the computer, the telephone and the radio were all rapidly evolving during that time,” says Martin. “It was also a period of social freedom, with women really starting to express themselves. Yet there were also these dark political forces on the horizon and a desire to return to ‘traditional values’. We now find ourselves in a very similar period. But you have to maintain a sense of joy and optimism, no matter how bleak everything seems.”

You can do that by taking cues from Martin and immersing yourself in the romance of summer and its playful dress codes. “Glamour is romance and I’m a secret romantic – I believe in joy, connection and beauty,” she says. “Getting dressed and creating a character for yourself every morning is a primal human urge. We were decorating ourselves before we painted cave walls.”

You can listen to the full conversation, recorded live in Cannes, on Monocle on Fashion below.

As Israeli and Iranian artillery continues to roar over the Middle East, and the world’s attention narrows in on military manoeuvres and nuclear threats, a diplomatic alternative is unfolding in the Arabian Gulf. In air-conditioned halls, behind closed doors in private majlises (sitting rooms) and through discreet backchannels, Gulf states are working overtime to contain the fallout from Israel’s strikes on Iran. At the centre of this effort is the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – a country uniquely positioned between two combatting capitals: Jerusalem and Tehran.

Israel’s initial attack triggered a wave of condemnation from regional neighbours. Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, Doha and Muscat have all issued carefully worded statements calling for restraint and warning of the dangers of escalation. On the surface, these reactions appear to be standard diplomatic protocol but beneath the language of international law and peacebuilding lies a more pragmatic aim: self-preservation. “The Gulf is scrambling to avoid a war between Israel and Iran,” says Mahdi Jasim Ghuloom, a junior fellow in geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation. “These public condemnations are not just about principle. They’re about protection, distancing Gulf interests from Israeli actions in the hope of avoiding retaliation from Iran.”

The concern is well-founded. Israel’s campaign, which prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu has described as “ongoing,” has already claimed the lives of high-ranking Iranian military officials, including the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the chief of staff for Iran’s armed forces. While the intent might be clear, the consequences are anything but predictable. “If Israel is serious about this being a longer-term operation, then the Gulf is right to worry,” Ghuloom warns. “There’s always the risk that Iran, feeling cornered, shifts into a regime-survival mindset. That’s when things become dangerous, when you start seeing unconventional retaliation, proxy activation or even nuclear miscalculations.”

In this increasingly volatile landscape, the UAE’s approach stands out. As one of the only countries in the world that is maintaining diplomatic relations with both Israel and Iran, the UAE occupies a rare position – not as a passive observer but as a potential bridge. While no formal mediation has been announced, diplomatic sources suggest that the Emiratis have been quietly keeping communication channels open with both sides, even during the peak of the ongoing Israel-Hamas war.

This balancing act has not been without friction. Israel’s recent decision to temporarily shutter several of its embassies in the Gulf, including in the UAE, to prevent Iranian retaliation, has raised eyebrows in the region. “It’s frustrating for Gulf leaders,” Ghuloom says. “Closing embassies signals a lack of trust in Gulf security and risks alienating countries that could be vital conduits for dialogue. If Israel wants de-escalation, the Abraham Accords can’t just be economic – they have to function diplomatically too.”

Signed in 2020 with great fanfare, the Abraham Accords promised peace dividends: trade, tourism, technology. But their true test is now. Can they deliver stability in a moment of rising danger? “The accords were never just about flights and free-trade zones,” says Ghuloom. “This is when they have to work, to channel frustration, to communicate red lines and to quietly nudge both parties toward restraint.”

Beyond the UAE, Oman condemned the strikes as “reckless” even as it remains a vital interlocutor in US-Iran nuclear talks. Should Muscat’s influence wane, Washington might turn to Abu Dhabi. “If Iran becomes unresponsive,” Ghuloom says, “the UAE could be the next best bet.” Saudi Arabia, too, is treading a thin line. Having restored diplomatic ties with Tehran in 2023, it has issued strong condemnations of Israel’s actions while signalling a more pragmatic posture – one grounded in a desire to reduce regional tensions rather than inflame them. This isn’t just diplomacy for diplomacy’s sake. The Gulf’s proximity to potential conflict zones (and its enmeshment with global markets) makes it particularly vulnerable. The largest US base in the Middle East is in Qatar, while thousands of US troops are stationed just outside Abu Dhabi. Any escalation risks pulling the Gulf directly into the fray.

Then there are the economic stakes. “Even without a full-blown war, the perception of instability will spook investors,” warns Ghuloom. The Gulf’s financial and aviation sectors depend on global confidence. If the region is seen as unstable, that flows straight through to currency pressures, trade dips and nervousness in the markets.” Airlines such as Emirates and Etihad rely on calm skies. Dubai’s booming property market is fuelled by foreign capital that thrives on certainty. Sovereign wealth funds from Abu Dhabi to Riyadh are now deeply exposed across global markets. For the Gulf, even a whiff of instability is bad for business.

In other words, it is pragmatism, not ideology, that is the guiding force behind Gulf diplomacy today. And as the region teeters on the edge of wider conflict, it might fall to the UAE, Oman and Saudi Arabia to keep it from tipping over. Not because they are neutral but because they are interconnected – and because, in a fractured region, they are among the few voices that are still speaking to both sides. For now, diplomacy remains discreet. But the stakes are anything but subtle.

What makes a good city? That’s a question that Monocle has grappled with since its launch. Why? Well, in 2007, as we surveyed the multiple city surveys that were already in existence, we were suspicious about whether the people who compiled them had ever visited the places that they scored so highly. While we all love a diminutive, wealthy city where ambulance-response times are short and the education system only churns out geniuses, what about having some unalloyed fun in the urban mix? A sense of freedom? A bit of sex too, perhaps (all rather curtailed in places where folks are in bed by 10pm).

Rather than just harrumphing about this state of affairs, we made our own survey, underpinned by hard data and including statistics for the softer elements of city life too, such as the ease with which you can expect to grab a glass of wine in a bar past midnight or buy food on a Sunday. We also had plenty of input from our correspondents, a wise but entertaining crowd. Over the years, the metrics have evolved with the times – for example, we have focused more on nightlife and the health of high-street retail since the coronavirus pandemic. But in truth, even in our survey, a relatively small set of wonderful cities has consistently triumphed as other places that we love have stumbled at the final hurdle – a city that scores highly for personal safety, say, might miss out because its public-transport system is kaput.

So, this year, we’re deviating from the old format and shaking things up. The 2025 Monocle Quality of Life Survey names not one but 10 winners: nine category champions and an overall star. The issue drops this week – it’s on newsstands from Thursday – so I won’t give the game away now. But here are five ideas that we put front and centre and how they led us to some interesting choices.

1. Safe streets

Everyone wants to live in a safe city – but at what cost? In some places where the crime rates are low, your every move is tracked by the authorities. Even your phone messages are available to prying eyes. Other cities are safe and have tight social cohesion but are terrible at making outsiders feel at home. So how come this thriving – but not the richest – European city is welcoming, multicultural, low on surveillance and super safe? I think that you’ll agree that it deserves its prize.

2. Health

Why are some cities blessed with such impressive longevity statistics? And believe me, it’s not because everyone is at the gym all day and living abstemiously. As we looked at the topic, we were led to a city where people like a drink and often smoke, yet stick around longer than their European city rivals. How? We’ll reveal all.

3. Housing

The lack of affordable housing has become a pain point in every city. Migration, tourism, local governments that have failed to invest – the issue has a long list of causes. But it’s possible to fix this. We have found a city that has stayed ahead when it comes to housing its residents.

4. Cleanliness

Again, this is something that we can all agree is a good thing (well, some people still think that graffiti is cool but they can stay out of this bit). Now, while you need the basics – regular rubbish collections, successful recycling programmes – there’s nothing that beats having engaged residents who care. In Monocle’s survey, you’ll discover a city that has almost no public bins – or dropped litter.

5. Good for start-ups

How can a city welcome entrepreneurs and create an environment where some risk-taking and experimentation are supported? And be a fun and affordable place to operate from too? Well, this plucky city, never ranked in any Monocle survey before, has taken the top spot because it has the answers.

You can read the Monocle Quality of Life Survey in our July/August issue, which is on sale from Thursday. Also make sure to visit monocle.com for a whole week of city-making debates.

A balmy evening and a picturesque setting provide the perfect backdrop to watch a film alfresco. Here we round up three upcoming cinematic events worth keeping on your radar this summer.

1.

Il Cinema Ritrovato

Bologna

Every June, Bologna becomes a must-visit destination for cinephiles as Cineteca di Bologna – a film library and foundation that plays a crucial role in the restoration and rediscovery of historic cinematic masterpieces – holds its annual film festival, Il Cinema Ritrovato.

Three open-air venues in Bologna – Piazza Maggiore, Arena Puccini and Piazzetta Pasolini – along with eight theatres will be screening a programme of 454 films spanning every era of cinema. One of the highlights of the event are the all-day “cineconcerts”, which pair silent films with live musical performances.

This year’s edition will feature works by pre-war Japanese filmmaker Mikio Naruse, a cinema retrospective by Austrian screenwriter Willi Forst and a selection from the Scandinavian norden noir film movement. There will also be a celebration of cherished Italian classics from Luigi Comencini.

festival.ilcinemaritrovato.it

Il Cinema Ritrovato runs between 21 and 29 June in Bologna, Italy.

2.

Film Noir au Canal

Montreal

Film Noir au Canal is a free, six-week film screening programme dedicated to cult crime classics and takes place every Sunday at 19.30 in Saint Patrick’s Square. Crowds of families, couples and lovers of old films attend to share the social experience. To ensure that the surroundings stay picture-perfect, the festival team has organised more than 60 clean-ups of the Lachine Canal area since 2008.

To maintain the noir mystery, the programme is not released until a week before the festival, which also includes musical performances and impassioned talks from genre experts.

Film Noir au Canal runs from 13 July to 17 August in Montreal, Canada.

3.

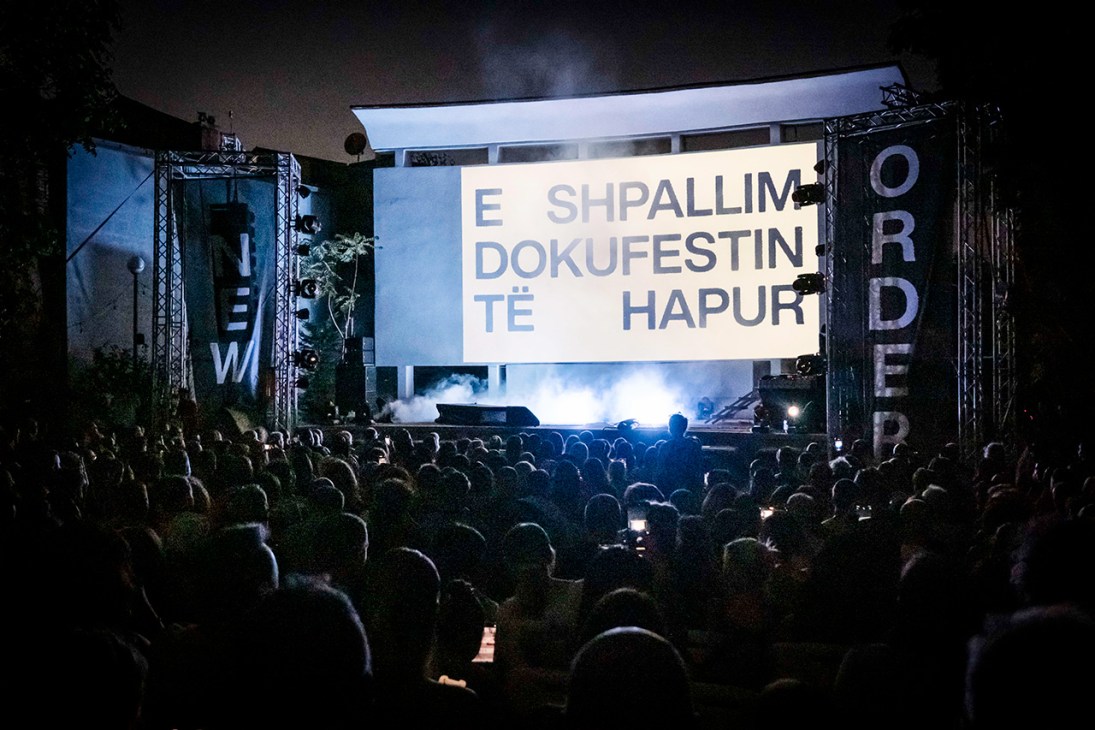

Dokufest

Prizren

For more than two decades, international documentary and short-film festival Dokufest has been one of the most significant cultural events in the Balkans. There are eight screening locations around the city, ranging from the open-air Lumbardhi cinema to the walls of Prizren’s historic fortress. A screen is even set up on the Prizren Bistrica river.

More than 200 films will be presented during the week-long event, most of which will loosely share a central idea. Though the theme is yet to be announced, you can expect the selection to include some of the best in documentary and short film. Last year, five of the screened titles were later nominated for Academy Awards. This year the programme will also include a new short-film forum for the first time, in which cinema centres in Kosovo, Macedonia and Albania will be brought together to help encourage funding and co-production opportunities in the region.

Dokufest also hosts panel discussions, masterclasses and musical performances, as well as workshops to introduce children to the art of filmmaking. “We strongly believe that the medium of documentary and short films are powerful,” executive director Linda Llulla Gashi tells Monocle. “They can change people and they can change politics.”

dokufest.com

Dokufest runs from 1 to 9 August in Prizren, Kosovo.

Another aviation accident, another three-digit coded Boeing airplane. After years of bad press dogged Boeing’s 737 line, the 787 Dreamliner now faces its first major reputational hit following the fatal crash of Air India Flight 171 on Thursday. While the exact cause of the incident won’t be known for many months, the disaster immediately resuscitated whistleblower complaints about production flaws in the wide-body aircraft – and proved that new CEO Kelly Ortberg’s turnaround efforts at the aerospace behemoth still have a long way to go.

The maiden voyage for Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner took place in 2009 at Paine Field, its flagship manufacturing facility in Everett, Washington. The Dreamliner doesn’t cut as dramatic a profile as the double-decker Airbus A380 and holds fewer passengers than the Boeing 777. But as the name suggests, it provides a smoother ride than its peers for long-haul flights with more comfortable cabin pressure, higher humidity, better air filtration, dimmable windows and anti-turbulence technology.

Like many global carriers, Air India has been stocking up on Dreamliners to replace an ageing fleet of 747s. While the Queen of the Skies is a beloved aircraft, the more fuel efficient Dreamliner is an ideal workhorse for flights between secondary airports, such as Thursday’s route from Ahmedabad to London Gatwick. Just last month, Ortberg joined president Donald Trump and Qatari emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani for the signing of a $96bn (€83bn) purchase agreement that includes 130 Dreamliners – the largest order for a single model of jet in Boeing’s history.

The blockbuster deal in Doha papered over lingering concerns about the Dreamliner, concerns that the Air India accident has now propelled to the forefront. The same year as the 787’s inaugural flight, Boeing broke ground on a final assembly line in Charleston, South Carolina, that could handle wide-body aircraft – only the third such facility in the world after Everett, Washington, and Toulouse, France. The move was widely interpreted as a jab at Boeing’s unionised workforce in Washington state, as South Carolina state law prohibits compulsory union membership. The powerful machinists and engineering unions crowed that the lower-cost non-union labour in South Carolina would build inferior airplanes.

Indeed, five years ago, Boeing discovered small gaps in the joins that could weaken the fuselage and production halted for two years to correct the issue. In 2024, whistleblowers testified before a Senate committee that Boeing had taken shortcuts and was “putting out defective airplanes,” an allegation the company denied by pointing to the thorough revamping of how it makes the Dreamliner’s carbon-composite airframe. The Federal Aviation Administration, which in the past has been accused of being asleep at the switch and effectively letting Boeing certify its own aircraft, oversaw the process. Media were also invited into the Charleston plant to see the improvements first-hand.

The Dreamliner that crashed on Thursday, however, was built in Everett by union machinists and delivered in 2014 (before Charleston fully took over wide-body production). Any potential problems with the flagship wide-body jets cannot be reduced to a simple question of union or non-union labour. There are perhaps deeper structural issues facing the inordinately complex engineering of a modern aircraft such as the Dreamliner; it’s also possible that a fluke, such as a flock of birds, caused the crash, as with Jeju Air Flight 2216 in December. Boeing will, of course, dispatch a crack team to assist US and Indian authorities with the crash investigation. In the immediate aftermath, Ortberg has the toughest assignment for any aviation CEO – damage control in the wake of a fatal disaster that has shaken the confidence of the public. Whether he can pass this test with flying colours will prove the true mark of the man who has taken on one of the most daunting leadership roles in global business.

Scruggs is Monocle’s Seattle correspondent.

Of all of the first lines in all 20th-century literature, the opening sentence of British author JG Ballard’s 1975 novel High-Rise takes some beating for drama, tension and an image likely to put pet-lovers’ teeth on edge:

“Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.”

Who wouldn’t keep reading? For the unfamiliar, High-Rise is a grizzly but brilliantly built tale of the moral and psychological descent of a group of middle-class professionals into the worst imaginable versions of themselves. The cause of their fall? Cohabitation in a vertiginous apartment block of the sort that was flying up across London at the time. Fifty years on, the issues at the story’s heart – community, placemaking, urbanism and what it means to live well – are as relevant as ever.

Nudged by subtle differences and barely perceptible social gradations (gleaned by floor, profession or proximity to services), the residents of Ballard’s nameless high-rise slowly swap community for chaos and civility for savagery in a way that clearly reflects the novelist’s suspicion that such architecture plays a macabre part. Though the principles of the high-rise were born through improved engineering and construction techniques, and couched in optimistic modernism (Swiss architect Le Corbusier called them “streets in the sky” and demanded dignity for all), it didn’t take long for the cheer to curdle.

Spurred by housing demands after the Second World War – and aided by craters left by Luftwaffe bombs – a new genre of hastily thrown-up residential buildings began to attract suspicion. Were these good places to house the many, or rangy receptacles for the sad and lonely masses? It’s no coincidence that James Bond creator and author Ian Fleming named his villain Goldfinger after the British-Hungarian architect responsible for several famous London high-rises erected in the 1960s and 1970s. Tall towers have always cast a long shadow.

High-Rise itself is a work of fiction but at its core lies the fact that the author, and many others, saw the new carbuncular modernism that defined mid-century building as atomising, oppressive, inhumane and anti-social. What’s more, many long-running issues and concerns with vertical living are becoming more relevant than ever. Cities today – especially London, where the novel is set – are struggling to find housing density to meet demands.

I mention all this because my circumstances recently changed to offer me a new perspective. Things began, well, looking up when renovations on my modest terraced home drove me – my wife, my young son and our cat Alfie – into the charity of a friend’s vacant, soon-to-be-sold apartment umpteen floors up overlooking east London. It was to be my first taste of an elevated existence.

Like the tentative early chapters of the novel (before things truly begin to unravel), our initial feelings were a breezy fondness for the fresh perspective. The lift, the mod cons, the gym, the big windows, the breeze and the maze of streets far below were intoxicating novelties. As time passed, this most artificial of platforms offered a glimpse of nature as I’d never seen before in the city. The sun rose and fell in a place where I’ve lived for 15 years yet rarely seen it. The city took on a thrilling new light: daylight, liberated from the shade most people experience between buildings, beamed brightly onto church spires, slate roofs, offices and landmarks, and trees budded and blossomed among the edifices. (Light, you realise, is the price the rest of us pay for the shadows cast by these tall towers).

Ballard’s book is a dramatic, twisted and preposterously dark but real version of what I – and more than a few snooty architecture critics – have long thought life at height must look like: a bit sad, insular and isolated. But as weeks passed, my concerns lifted too. Time was measured not by the feeling of being trapped but by a sense of freedom: in lemony-hued sunrises of early spring and dramatic sunsets of deep-red and bruise-purple over a city I saw anew with each change of weather. Over time, the rhythms of the street, commuters, partygoers, buses and taxis – although Lilliputian – seemed all the more poignant and pretty when experienced from above. By the time we came to abandon our experiment with altitude, even some of the initially unfriendly, eye-contact-avoiding lift-dwellers and neighbours warmed up and began exchanging pleasantries. It was a lot more Corbusian cheer than Ballardian bleakness. People, I can confirm, are mercifully much the same in the sky as on the street.

So, could building more high-rises still be a viable solution to London’s housing shortage? Today, more than at any time since Ballard’s book was published, cities are redrawing our relationship with our lofty neighbours. While taller buildings should be appealing (if only for the number of units they can offer in a smaller space) there’s fresh backlash against the housing blocks that have been part of planning orthodoxy for the past half century. In the UK this is partly due to the unnerving prevalence of flammable cladding that was exposed after the Grenfell fire tragedy that cost 72 lives in 2017 and commemorates its eight-year anniversary this weekend. Not to mention the many well-built, well-intentioned blocks that have succumbed to neglect, decay and ghettoisation, and the newer ones being thrown up by corner-cutting developers. To top it off, the UK’s unnecessarily complicated and often unfair system of leaseholds and service charges doesn’t make ownership appealing either. Lastly, there’s the post-pandemic pushback against small flats without green space as a response to shifting expectations of homes in the busy city. Challenges aside, this need not be the death knell for urban density.

Designed well with careful consideration for the proportions, neighbours, services and connection to the street, tall buildings can be beautiful and do not necessarily presage a collapse in community. The water did go off in the block once (for an hour or two) but I’m happy to report that this was the extent of the blight and there was no further descent into a Hobbesian hell. We didn’t once consider barbecuing the cat.

High-rises can be exciting, elevating and an integral part of the city’s texture and should be big and bold enough for more than one genre of family, home and lifestyle. Of course, there are downsides but perhaps it’s time to drop the snobbery, lower our guard a little and give the high life another chance.

Josh Fehnert is Monocle’s editor. For more on global affairs to business, culture and design, subscribe to Monocle today.

It’s no secret that the high street, once the vibrant heart of our cities, has seen better days. Last year in the UK alone, 13,479 high-street shops closed permanently – a staggering average of 37 closures per day – according to the Centre for Retail Research. Economic headwinds have certainly played a part, with an increase in rents, the rise of the digital marketplace and shifting consumer habits all contributing to a slow but sharp decline. The result? Less vibrancy, fewer characterful shopfronts and more homogeneous streetscapes dotted with the usual chains. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

In Wandsworth, southwest London, a new development is offering a bold counterpoint. New Acres is a £500m (€587m), 50,000 sq ft purpose-built neighbourhood designed with one clear goal: to prioritise independent retail. The numbers are impressive: 1,034 new rental homes (35 per cent of which are affordable, meaning that rents are at least 20 per cent below local market rates) and 40 independent shops, as well as a makers lab, wellness studios, co-working spaces, market stalls and podcast studios. “It was really important to ensure that we had a curated approach to the environment,” says Denz Ibrahim, head of futuring and place at Legal & General. “We want to create an independent neighbourhood. If we followed a traditional route, the brands wouldn’t resonate with us or our residents.”

The most radical detail? More than half of the shops at New Acres will be offered a year of free rent, creating a soft landing for new ventures and small businesses. “We wanted to celebrate independent brands,” says Ibrahim. “For us, that means either a first or second shop or a company relocation from an existing site. This is about making something that’s civic and democratic and that faces one of the biggest challenges in retail today.”

Instead of putting all businesses on equal footing, New Acres wants to champion the diversity that makes each of these ventures so rich and distinctive. After the first rent-free year, companies will be placed on performance-based rents, whereby payment is calculated as a percentage of the revenue to reduce financial pressure and allow for growth. This is all part of a three-year starter package that comes with marketing support and a “white box” space to allow for easy customisation and branding. “We want people to stay in New Acres because they love living there, so we need to ensure that the neighbourhood looks outwardly and blends with the community,” says Ibrahim.

What New Acres proposes is a reminder of the importance of being selective with retail offerings to ensure that local businesses are given a fair shot against established brands. That’s why schemes such as Lisbon’s Lojas com História (Shops with History) have been seen as models for other cities. Launched in 2015, the programme now has more than 160 shopfronts under its umbrella, ranging from century-old cafés to glove-makers and artisanal grocers. The spaces are protected from rent hikes and receive tax incentives to ensure that heritage brands stay put. In neighbouring Barcelona, a protected-establishments registry was created to safeguard historic businesses from eviction or rent spikes, while Tokyo has long preserved its traditional shotengai (shopping streets) with zoning laws that favour low-rise buildings.

Be it safeguarding beloved institutions or offering a platform for the next generation of shopkeepers, supporting independent retail is about more than economics. It’s about civic pride, urban character and creating places where people want to live and linger. “We are a long-term investor, so we have a long-term view,” says Ibrahim. “Everything we do is based on two things: making incredible places for people and ensuring that it’s future ready.”

To hear Monocle’s full interview with Denz Ibrahim, listen to the new episode of The Urbanist.

“It looks like a showroom!” said a friend at my flat-warming party. It wasn’t meant to be mean-spirited but it hurt nonetheless. My heart sank as I realised that there was some truth in the statement. The sofa still smelled new, tables were carefully laid out with magazines and incense, and the bookshelves were stacked with design titles (a perk of editing The Monocle Minute on Design’s ‘In the Picture’ segment below). I had unintentionally created a showroom.

For weeks afterwards, I mussed up the coffee table every time I stepped foot in my living room, making a point to crack open unread books to pore over some pages. I was determined to accelerate the process of breaking in my new space, airing out any whiff of inauthenticity. Eventually, a respectable amount of clutter began to build up and I was comforted by these signs of life (though my better, neater other half might not have felt the same way).

It’s funny how design can, at times, feel more like a performance than something to be enjoyed. And pinpointing exactly where the former begins and the latter ends is admittedly an esoteric pursuit. A recent rewatch of French filmmaker Jacques Tati’s 1958 comedy, Mon Oncle, laid this dichotomy bare. The uncle in question, Monsieur Hulot, represents the average Frenchman struggling to make sense of the consumerist culture and modernist architectural boom that swept France after the Second World War. His growing obsolescence is conveyed through the old-town apartment that he lives in and the rickety bike that he rides.

Meanwhile, his sister, Madame Arpel, eagerly embraces this wave of technology. She lives in a new suburb, in a sleek, white house with a state-of-the-art kitchen in which she proudly stages demonstrations for her fellow housewives. One can only assume that Le Corbusier and Charlotte Perriand featured on the set-design team’s mood board. A recurring gimmick in the film is a fish-shaped fountain that she switches on to impress only the worthiest of guests (pictured, above). It’s through her possessions that Madame Arpel finds a sense of security and status.

In truth, I quite like the ultra-modern house and the flashy pieces that furnish it. But Tati skilfully and rightly pokes fun at an attitude to design that’s more about performance than enjoyment or personal taste. After all, who wants to live in a showroom?

It’s a tumultuous time for the US – and Apple is caught in the eye of the storm. Donald Trump wants Apple to build its iPhones in America, which could lead to their price increasing to more than $3,000 (€2,612). According to CEO Tim Cook, US-imposed tariffs could cost the company $900m (€783m) in the next quarter alone. Meanwhile, the EU is forcing Apple to open up parts of the iPhone to third parties, while there are also legal pressures on its App Store and delays to its own heavily-trailed artificial intelligence.

Nevertheless, the mood was calm and serene when Apple opened its Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) in California on Monday. WWDC is an annual shindig designed to show app developers the company’s software plans for the coming year. Though there were mentions of Apple Intelligence, the iPhone maker switched its focus to what it called its “broadest design overhaul ever”.

The new software will launch in autumn for the iPhone, iPad, Mac and Apple Watch, with a new discreetly opulent look called “liquid glass” that’s inspired by the translucent interface of the company’s headset, the Apple Vision Pro. The camera will be redesigned in a bid to simplify how it works, while travellers will be able to hold their passport on their iPhone for domestic travel. A great deal of thought has also been given to the Phone app. You know, the one after which the device is named, and which does that charming, old-fashioned thing: make and receive calls.

For instance, if waiting on hold seems tiresome, the phone can automatically recognise hold music and offer to keep your place in line, mercifully muting the audio until you’re linked to a human agent. When that happens, the phone rings to rejoin you to the call, while telling the other party that you’re on your way. Apple also announced “call screening”, which pre-emptively asks a caller from an unfamiliar number to state their name and reason for calling. The answers are displayed as text on screen and you can decide to answer or ditch the call.

Similarly impressive was a live translation feature, which visually and audibly relays what is said between parties using different languages in real time. In a demo, it was clear that the pause between speaking and translation was fast, though I suspect it works best in a quiet environment. Something similar can be done with text messages: received messages appear translated on screen as they arrive and outgoing messages can be translated to suit the recipient’s needs.

These capabilities are powered by artificial intelligence (AI). AI is important, Apple suggests, but instead of being a feature in its own right, what’s more important is how the new, clever stuff will be infused across the brand’s phones, tablets, watches and laptops, from now on. Before Monday, Apple looked like a company anxiously dealing with an onslaught of problems. Now it appears confident – even optimistic.

Last week’s astonishing remote-controlled attack by Ukraine on five Russian airfields – some of them thousands of kilometres from the frontlines – might have changed warfare forever. Militaries all over the world, once they have finished marvelling at the ingenuity, diligence and bravado required to launch blizzards of drones from trucks driven to their targets by unwitting citizens of the nation with whom you are at war, will fret furiously about what it will mean.

How can military installations be defended in a world where they can be hit anywhere, from anywhere, and by weapons that will not alert any radar? Is there really any point in spending billions of dollars on hi-tech aircraft when it might be demolished by cheap, disposable toys armed with munitions that can be partly manufactured with 3D printers? How confident is the commanding officer of any airfield about the benign nature of every single shipping container that might happen to be, at any given moment, within a few hundred kilometres of their control tower?

We recently heard from a Monocle reader with inadvertent insight into a specific aspect of this sort of warfare – what might be thought of as a dramatic decentralisation of military procurement. The reader had put a 2021 DJI Mavic 3 drone up for sale on Ricardo, which is essentially Swiss Ebay. He’d been contacted by a Ukrainian who explained that he was sourcing drones for Ukraine’s military and that older models were easier to override for combat purposes. The buyer offered to send a photo of the drone in action once it was repurposed (our contact duly received a photo of a Ukrainian soldier holding a drone which was, if not exactly the same one, a similar model).

I contacted the purchaser, who explained that there are small, informal networks of Ukrainians that are crowd-sourcing military materiel all over Europe; the cells are based on pre-war social and professional relationships linking the buyers with serving soldiers. The Swiss connection benefits from the country’s characteristically punctilious restrictions on drone use. “Swiss kids buy drones for fun,” the buyer says, “then realise that they cannot fly everywhere and sell them for half-price.”

Eager though the sellers may be, they are duly informed of the use to which their drones will be put. A small number maintain traditional Swiss neutrality and decline but, according to the buyer, “In 99 per cent of cases, the Swiss are very happy to help, and offer discounts and pack bars of chocolate into drone bags. The fact that most Swiss men have served in the military and know how army life works helps a lot.”

The necessary funds are privately raised. The buyer reckons that they alone have sent nearly 100 Mavic 3 drones to the Ukrainian army since the war began in 2022. “The drones have a very short life span,” he says, “but it’s still better to send a drone to check whether there are any Russians around the corner than to send a soldier.”

But the question – well, a question – now plaguing strategists is where these leaps forward in drone technology might be leading. The weekend before last, I attended the Black Sea Security Forum in Odesa – one of many Ukrainian cities that has been used, over these past three years, as an unwilling and undeserving testing range for drones built by Russia and Iran.

Among the people I met was a British military analyst and former soldier who told me that the evolution of drones was now proceeding so rapidly that generations of development were measured not in years or months but weeks: the Turkish-built Bayraktar TB2s, which had inspired folk ballads in the early stages of Ukraine’s resistance in 2022, now seemed like positive antiques. This is not to say that we will not hear more of Bayraktar – just a few weeks ago, the AI-powered Bayraktar TB3 became the first drone capable of completely autonomous liftoff and landing on a short-runway vessel; it can stay in the air for 32 hours and launch supersonic ballistic missiles.

The analyst reckoned that in future conflicts, large-scale deployments of infantry would be all but impossible, massed-armour formations would be hopelessly vulnerable, and that mileage in crewed fighter jets would swiftly decrease. He also noted that in the Black Sea lapping at the shore down the street, Russia’s fleet had recently been defeated by a country without a navy.

He wondered vaguely whether we were on the verge of outsourcing warfare entirely to machines and androids belting the nuts and bolts out of each other, with every offensive innovation thwarted almost instantly by defensive countermeasure. It’s hard to know whether it sounds dystopian or utopian: what do wars become if people can’t fight them?

Andrew Mueller is a contributing editor at Monocle and host of our weekly world affairs podcast, The Foreign Desk.

For Monocle’s June issue, we profile 10 European defence disruptors. Click here to read more.