The artisans battling to keep craft alive with achingly beautiful creations

Monocle looks at the ways that artisans around the world are preserving ancient skills and processes by making sure that they remain relevant and desirable in the modern world.

The upholsterer

Wigrens Döttrar

Stockholm, Sweden

Based in Stockholm’s Södermalm district, upholstery atelier Wigrens Döttrar is a beloved part of the city’s urban fabric. “The community around here is close-knit,” says owner Sara Lidenmark. “Locals pop by to have a chat every day and many of my clients live in the area.” That friendly, inviting rapport is central to the workshop’s reputation. “Sometimes I’m even invited to dinner at clients’ homes.”

Opened in 1926 by upholsterer Anton Wigren, the studio is now managed by Lidenmark. She joined in 2012 after completing an apprenticeship with the then-owner, making her the fifth artisan to head the studio. “For as long as I can remember, I’ve had an interest in beautiful fabric and furniture with a history,” says Lidenmark. “It’s magical to see a piece transform from something tired into a beautiful object.”

A look at Lidenmark’s order book shows locals putting in requests for the upholsterer to spruce up their armchairs and sofas. But she is also working with larger clients such as restaurants and museums. With such a variety of projects, Lindemark runs a tight ship. “Upholstering is a very creative process,” she says. “It gets quite messy when I’m working on something but I’ll have a moment after I’ve finished to stop and clean it all up. Then I’m ready to move on to the next piece.”

On the day when Monocle visits, Lidenmark is about to put the finishing touches on cushions destined for an outdoor-seating area on a roof terrace. It’s a slightly unusual job for her – but she has just as much fun with it as she does with any other project. “I love working here and having such close ties to the neighbours,” she says. “It feels so special to carry on the history of my forbearers in this spot.” Lidenmark says that she isn’t alone in that sentiment. “People know the history of this place – they want it to live on.”

wigrensdottrar.se

The weaver

Antico Setificio Fiorentino

Florence, Italy

A few minutes’ walk from the waters of the Arno, Antico Setificio Fiorentino is one of the last vestiges of Florence’s golden age of craftsmanship. The city’s old-world San Frediano neighbourhood would have once bustled with artisans. Now though, the workshops are far fewer in number and weaving ateliers like this 18th-century remnant have almost disappeared from Italy.

The team at Antico Setificio Fiorentino is determined to keep their practice thriving. “This isn’t a museum or a foundation – it’s an actual business,” says Fabrizio Meucci, a third-generation technician who handcrafts replacement parts for the heirloom equipment. “The task of keeping the company alive motivates us to work harder.”

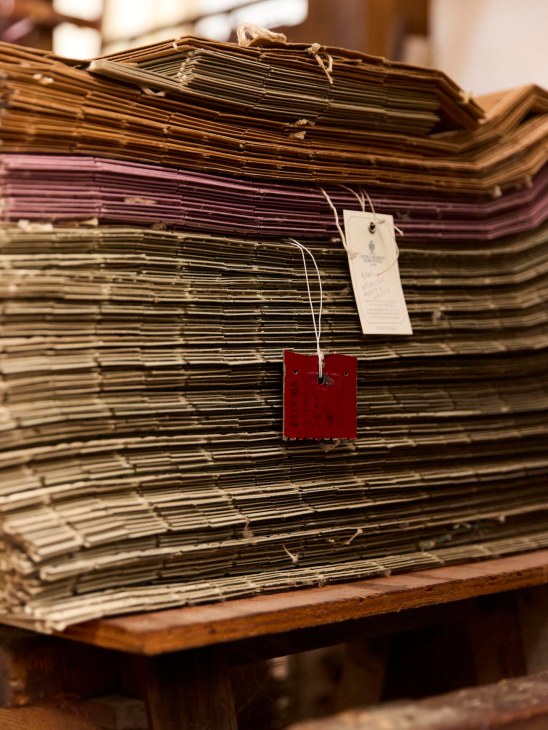

Every working day, the team weaves threads to turn out silk fabrics, from intricate fleur-de-lis jacquard to glossy satin. The more modern 19th-century looms produce 10 metres a day. The oldest wooden-framed contraption dates back to 1650 and turns out just a metre or two of fabric a day.

The space echoes with the percussive sound of the looms. Clients arrive to leaf through the fabric archive that includes Medieval and Renaissance-era designs. Some are looking to make purchases for hotels and churches. Others are drawing up plans for custom patterns or commissioning reproductions of historical materials.

The sense of how important the atelier is to the city is signified by high-end Florentine menswear brand Stefano Ricci’s decision to acquire it from locally based fashion house Pucci in 2010. “[The process was about] safeguarding the artisan techniques needed to make these fabrics,” says team member Maria Rita Agliolo Gallitto. For Pucci, it was important that the buyer was also a Florentine.

Despite the changes, the weavers have remained at the looms. And local homes and institutions will continue to shimmer with the intricacy and splendour of Florence’s ancient weaving craft for a long while yet.

anticosetificiofiorentino.com

The carpenter

Mogami Kogei

Tokyo, Japan

As the only son of a craftsman in edo sashimono (traditional Tokyo-style joinery), Yutaka Mogami always planned to join the family business. Playing in his father’s workshop from early childhood, he entered the craftsmen’s ranks at the age of 23. “In this part of Tokyo’s historical Kuramae district, there used to be workshops making sashimono furniture, platformed geta sandals, woodblock ukiyoe prints and more,” says the 71-year-old Mogami. “But now many of them have been replaced by apartment buildings.”

Despite this, makers remain central to the community in Tokyo’s old downtown area. Mogami’s workshop has been in business for more than a century – and the ability to change with the times has been key to its longevity. While Mogami’s father passed on his craft by training 12 apprentices, co-founding the Edo Sashimono Co-operative Association and paving the way for the craft’s official national recognition, Mogami has sought to merge traditional joinery techniques with modern designs. Keeping the studio open and accessible to visitors is key to its success.

“Many people arrive with an idea based on something that they’ve seen in an exhibition or in a relative’s home,” says Mogami. Sets of drawers are made to order from wood native to Japan, such as zelkova or paulownia, while family Buddhist altars and paper andon lanterns finished with urushi lacquer are also popular choices. “I’ve even been asked to make a gunbai, the wooden baton used by the referee in sumo wrestling bouts.”

Mogami isn’t shy about letting customers see him at work. Seated on the floor with his chisels, hand-planes and saws, he crafts dovetail joints and beveled edges entirely by feel. It’s a process that reinforces the value of sashimono – these meticulous details are often concealed within the finished product. “A true craftsman finishes each and every detail, even those parts unseen.”

sasimono.ciao.jp