The designers bringing slow fashion to New York’s rapid retail scene

Is it time to slow down in the fashion capital that has always moved fastest? We take a look at upstart brands to find out.

In late 1960s and 1970s New York, it was possible for a young Ralph Lauren to turn a fledgling neckwear business into a multi-billion-dollar fashion and lifestyle empire; or Belgian-born Diane von Furstenberg to transform a single jersey dress design into a global luxury label – all while partying at Studio 54 with Andy Warhol every other night. The Garment District was buzzing with designers’ orders, while fashion-magazine editors operated with unlimited budgets and American department stores from Bergdorf Goodman to Barneys were widely recognised as luxury temples, where well-heeled city dwellers returned on a nearly daily basis to restock their favourite perfumes, place made-to-measure orders for Oscar de la Renta gowns or pick up fresh flowers. Most will agree that this version of the American dream – where growth happens at lightning speed, volumes are always high and margins even higher – is well behind us.

Today the city’s creative scene paints a different picture: Barneys has shut up shop, while the likes of Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus are undergoing major consolidation. Designers are trying to come to terms with New York’s rising costs of living and the effect of potential import tariffs under the Trump administration. The Garment District has been dramatically downsized and many creatives seem to have swapped Manhattan for the city’s suburbs. The growing obstacles are impossible to ignore – as is the sense of tension on New York’s streets and subways.

Still, amid the challenges a new creative wave of designers and retailers is emerging – and working together to redefine the American dream. They might no longer aspire – or be in a position – to roll out their concepts globally, like their predecessors, but they are fostering intimate connections with customers closer to home, while setting ambitious quality and manufacturing standards for themselves and shifting the focus back to the needs of their clientele. In other words, it’s back to basics for the fashion community of New York.

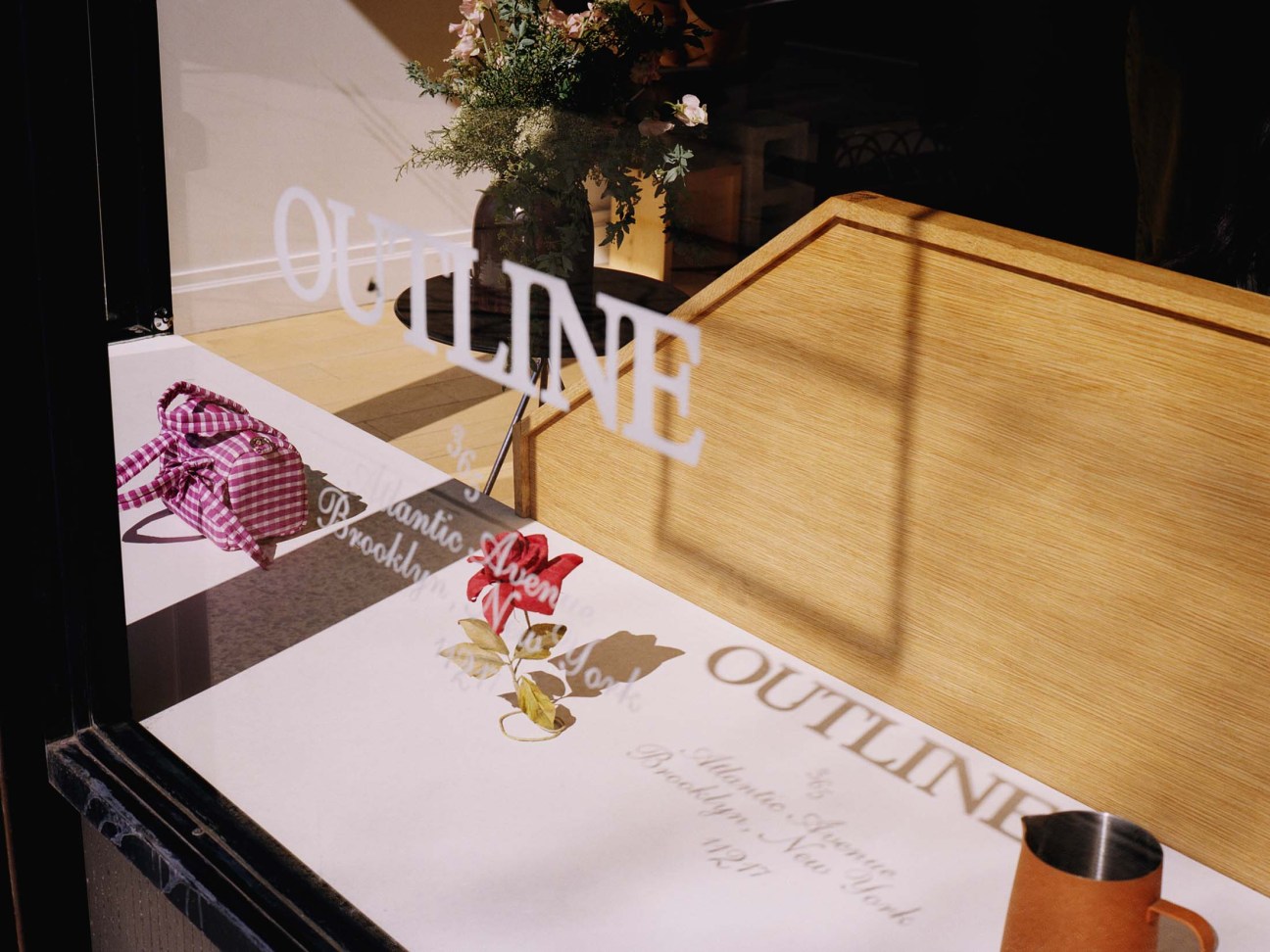

“We aren’t looking to reinvent the wheel, because it wasn’t broken,” says Margaret Austin, a Brooklynite and fashion buyer, who learned her trade at boutiques such as Opening Ceremony. “We want to bring back the neighbourhood shop and service the women in the surrounding areas.” In 2022 she joined forces with her friend and neighbour Hannah Rieke to open Outline Brooklyn, an elegant boutique on Atlantic Avenue, a short walk from both their homes. The shop carries some of the world’s most in-demand luxury brands, from The Row to Maison Margiela and Dries Van Noten, alongside up-and-coming names such as Beirut’s Super Yaya and London’s Kiko Kostadinov. “It’s a mix of brands that feel very special but they’re also wearable and make sense for the women who live in this neighbourhood,” says Austin, explaining that there is always a sense of ease in the items she picks up for the shop. “These are clothes for people who walk the dog before work, who commute and go to dinner straight from the office,” she adds.

Despite the impressive designer line-up, the shop maintains a laid-back feel with its minimalist wooden furniture and cosy terrace, and the Rieke’s bike parked casually in a corner. “It was really important to create a warm space where people feel comfortable; some luxury shops are so pristine that they feel untouchable, almost like museums,” says Rieke, stressing that this space will remain the heart of the business. “We just wanted to create one excellent shop,” adds Austin. “Aside from a pop-up here and there, we don’t have huge ambitions to grow and open a million new doors. We’ve seen what aggressive growth can do to a retail business. So many great shops that worked well on a regional level have had to close down.”

This hyper-localised approach is Austin and Rieke’s answer to the traditional fashion business model, which tends to prioritise scaling up above anything else. It has also proven to be an antidote to the fatigue surrounding online shopping.

“We’re tired of doomscrolling,” says Rieke. “There is way too much product out there; it’s almost like going grocery shopping. But it seems that the pendulum is now swinging.” To that end, success for the Outline team isn’t equated to acquiring thousands of new customers but ensuring that locals keep coming back. “When a new person comes in, there’s a 95 per cent chance that they’ll become a returning customer,” adds Rieke. “We’re fortunate to have this type of response and it allowed us to keep going – [in 2024] sales were up nearly 40 per cent.”

Rieke and Austin aren’t alone: a short walk from Atlantic Avenue, you’ll find Ven Space in leafy Carroll Gardens, a meticulously put-together menswear boutique that carries best-in class names from Lemaire and Auralee to Comme des Garçons. Just like Outline, the boutique has little online presence. Instead, founder Chris Green is investing his time into getting to know local customers on a first-name basis, offering one-on-one styling appointments and reintroducing intimacy to the shopping experience.

New York’s designers, both new and established, have also been rethinking what a successful business model looks like and returning to basics. “We’ve become so provincial; our lives are really rooted here,” says Lilly Lampe, a former art critic who moved to New York from Georgia and co-founded Blluemade with her partner, Alex Robins, in 2015. After some experimentation, their label has become a go-to for corduroy and velvet “Made in New York” garments. “The proximity to the expertise of the Garment District is what keeps us creatively stimulated,” says Robins. He explains that despite rising production costs, “little city support” for the Garment District and countless attempts to move it from its historic Midtown Manhattan neighbourhood, committing to local manufacturing has allowed the brand to maintain its high standards and stand out in the crowded market. “Textile has always been the most important tool we use. Whatever we’re doing, we’re choosing the best fabrics and that’s something that retailers, such as United Arrows, have always appreciated,” adds Lampe.

Their workwear-inspired silhouettes, from double-pleated trousers to artists’ overshirts and sharp corduroy jackets, also eschew the concepts of seasonal trends in favour of a slower design approach. “It should feel as though you’re opening your grandfather’s wardrobe and picking an item,” says Robins. “You don’t know which decade it’s from; you just know that it’s a great design and you want to pick it up.”

Their limited-edition collections might seem a world away from those of uptown designers who host runway shows, partner with department stores and produce their designs in larger quantities in Portugal or Italy. Yet even some of New York’s most recognisable names have gone back to thinking locally, in order to survive the tougher market conditions. Take Marc Jacobs, former creative director of the world’s largest brand, Louis Vuitton. After many trials and tribulations attempting to scale his namesake label, Jacobs decided to focus his premium line on his home market, presenting two small collections a year and selling them exclusively at Bergdorf Goodman in limited quantities.

The new generation of designers are following in his footsteps. Jac Cameron for instance, a former designer at labels such as Calvin Klein and Madewell, launched her label Rùadh last year with the ambition of offering the most considered, sustainably made denim in the luxury market. Operating out of her chic Tribeca loft, filled with mid-century furniture and romantic mood boards of her native Scotland, she has been working on perfecting her label’s signature silhouettes (straight leg trousers with subtle pleats running down the middle and curved jackets featuring recycled hardware) and producing them in small batches in specialist factories in Los Angeles. It’s a far cry from the previous generation of American denim brands, which outsourced manufacturing to China and targeted the mass market.

“I have spent some time thinking about how to craft a brand relevant to the current moment,” says Cameron. “There’s so much out there at every level of the market, every price point. So you have to create products that are made sustainably and have lasting power in terms of the way they are structured, washed and designed. My first collection was made up of 11 pieces, made in a high-end factory in Los Angeles using less water, fewer chemicals and recycled hardware. Every element is considered and I’m very intentional about how to grow the brand.” Even if opportunities for growth are slower than they used to be, Cameron (who moved to New York for an internship with Marc Jacobs 20 years ago and never left) thinks that the city still has plenty to offer for creative entrepreneurs. “The talent you have access to is unmatched,” she says, pointing to a network of creative New Yorkers from writers, to models and stylists who started supporting Rùadh from early on. “There’s a return to more niche companies that focus on gathering smaller groups of people and building communities. New York is still a great place for this: if you think of the footprint of Manhattan, it’s actually quite small, so you always have chances to make new connections here.”

Rùadh has been seizing these chances and finding ways to grow in a more sustainable manner. For the latest edition of New York Fashion Week in February, Cameron partnered with luxury retailer Moda Operandi (its only wholesale partner) to introduce a handful of new items, including workwear-inspired jackets, skirts and “Made in Scotland” knits. “I’m not trying to produce 5,000 units of each item,” she says. “It’s all about small batches, the right partnerships and a return to craft,” she adds. “I want to meet skilled artisans doing interesting things in an industry that hasn’t been disrupted in a very long time.”

A few minutes down the road, Maria McManus, another up-and-coming name, is building her own slow-fashion operation based on near-identical values. Her eponymous label is best known for fully fledged ready-to-wear collections, ranging from breezy shirts made with organic cotton sourced in Japan to suits made from Portuguese linen and wool blazers featuring biodegradable corozo nut buttons. “The 21st century needs to be about collaborating with nature, rather than using and abusing it,” says the designer. “I would never have done this if it wasn’t about sustainable manufacturing – nobody needs another brand. People are talking about issues with inventory, synthetic micro-fibres and so forth. But few designers are actually doing anything about it.”

To that end, McManus has carved a niche for herself by developing a network of specialist boutiques from around the world that now carry her collections. Online retailer Net-a-Porter has also come on board this year as the brand’s only larger-scale partner. But even as McManus gains more global recognition via tie-ins with such platforms, she is staying focused on keeping production runs small and operating as locally as possible. In fact, much of her production still happens in New York, while her creative process, operations meetings and client appointments take place in her living room-cum-studio in Tribeca. “There’s so much happening on our doorsteps, so many New Yorkers focusing on mindful design,” she says. “It’s refreshing, after that long period [before the coronavirus pandemic] when the city went through an influx of venture-capital money and local brands expanded too quickly, becoming soulless.” She now sources furniture from a French antique dealer who lives in the same building, buys her groceries from the local farmer’s market and invests in art from a nearby gallery.

Venture-capital investments might be drying out but New Yorkers like McManus and Cameron are ready to usher in a new era, where less is more. McManus recently hosted customers at her loft for an evening of drinks, clothing try-on sessions and basket-weaving tutorials with bag designer Erin Pollard – an event that captured local designers’ renewed focus on privacy and one-on-one connections. “We’ve all become bored of big brands, big restaurant groups and mass homeware shops,” says McManus. “We’re at a point where we want to be more thoughtful about every aspect of our lifestyles: what we wear, what we read, what we put in our homes.”

It might finally be time to slow down and take stock, before forging on with the path ahead. Even for New York’s fashion-forward, high-speed urbanites.

blluemade.com; outlinebrooklyn.com; ruadh.com; mariamcmanus.com

Address book:

Menswear haven:

Ven Space

369 Court St, Brooklyn, NY 11231

Best curation:

Outline Brooklyn

365 Atlantic Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11217

For modern-day Americana:

Wythe

59 Orchard St, New York, NY 10002

Post-shopping lunch:

Fanelli Café

94 Prince St, New York, NY 10012

Designers’ favourite watering hole:

Clemente Bar

11 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10010

All-time classic:

The Odeon

145 W Broadway,

New York, NY 10013

Best interior design:

Khaite

828 Madison Ave,

New York, NY 10021

New in town:

Destree

837 Madison Ave,

New York, NY 10021

By appointment:

The Future Perfect

8 St Lukes Pl, New York, NY 10014