Salone del Mobile

Right up our street: Cities as design objects

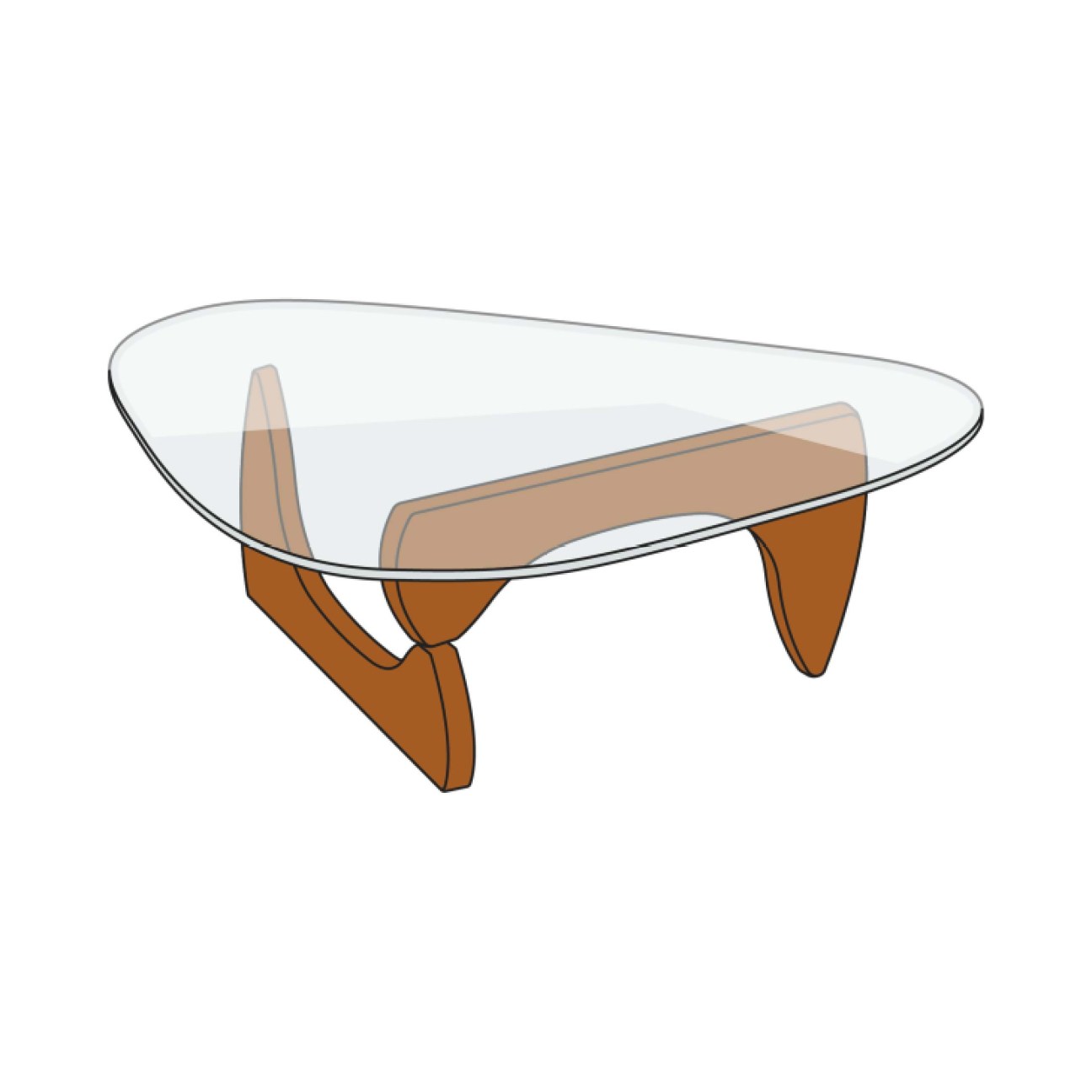

1.

New York

USA

Japanese-American artist and designer Isamu Noguchi created this coffee table in 1947 for Herman Miller. At the time, Noguchi was living in New York – and we think the jazzy curves of this piece echo the modernist spirit of the city perfectly.

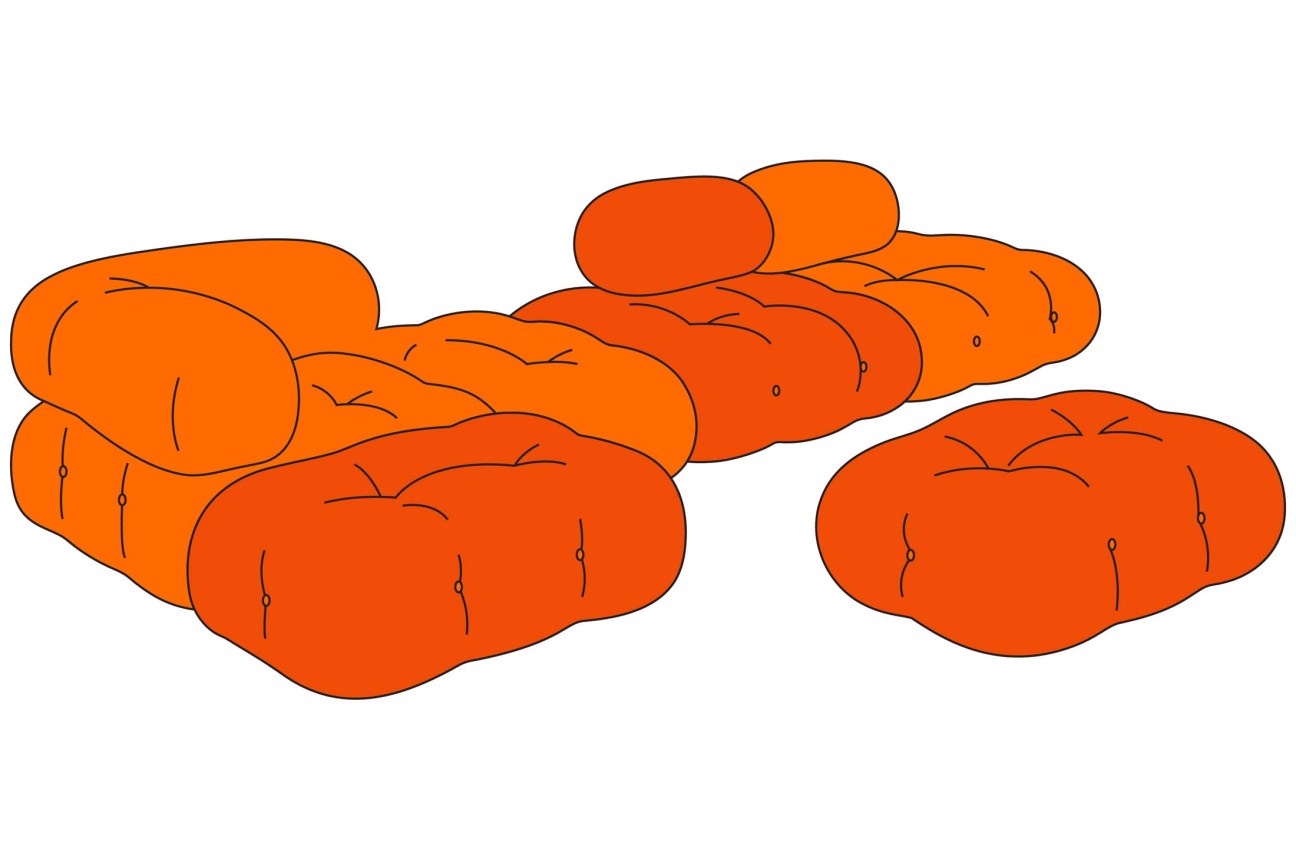

2.

Milan

Italy

Plush, wildly popular and a little bit sexy, the 1970 Camaleonda sofa system by Mario Bellini is Milanese design at its best. Proudly Italian in its roots – as well as an international bestseller – the Camaleonda could only come out of Milan.

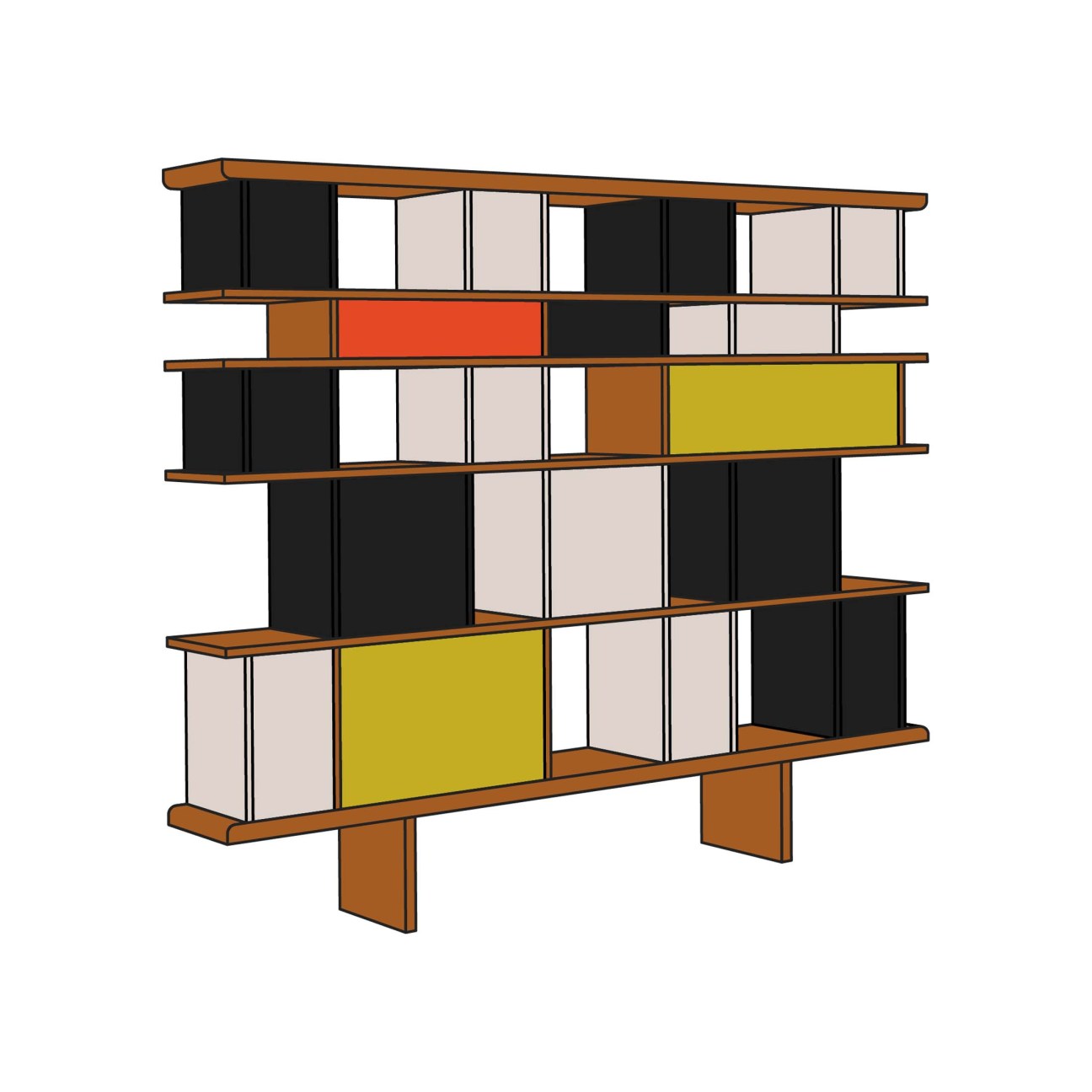

3.

Paris

France

This 1950s Nuage bookcase by Charlotte Perriand is decorative and complex, much like Paris. Imagine it in a Hausmannian apartment, displaying French literary classics and providing an elegant backdrop at Château Margaux-fuelled dinner parties.

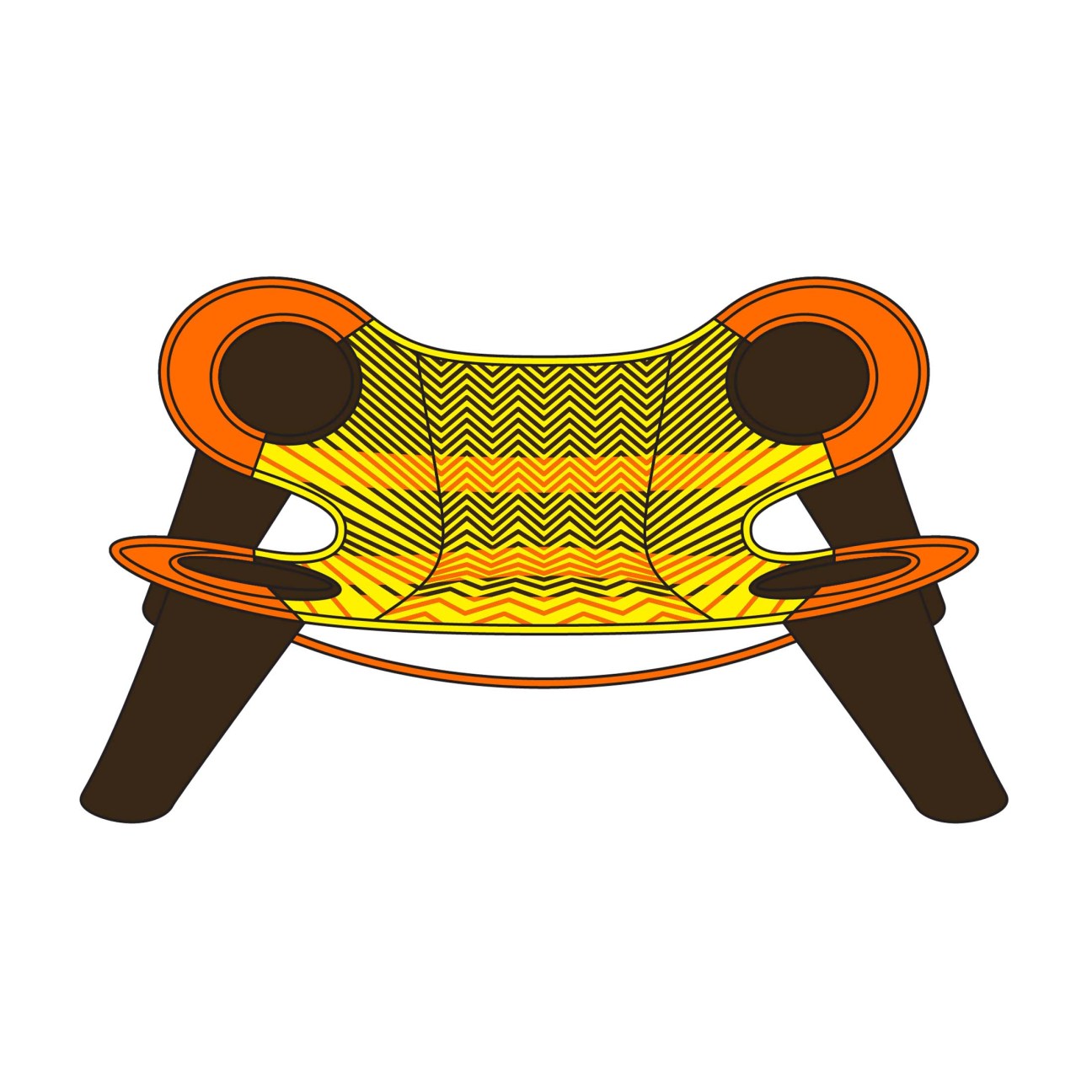

4.

São Paulo

Brazil

This wooden stool by Italian-born Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi was produced in the 1980s for the SESC Pompéia in São Paulo, a vast sports-and-culture centre. Democratic in spirit and with a playful silhouette, this perch flies the flag for São Paulo.

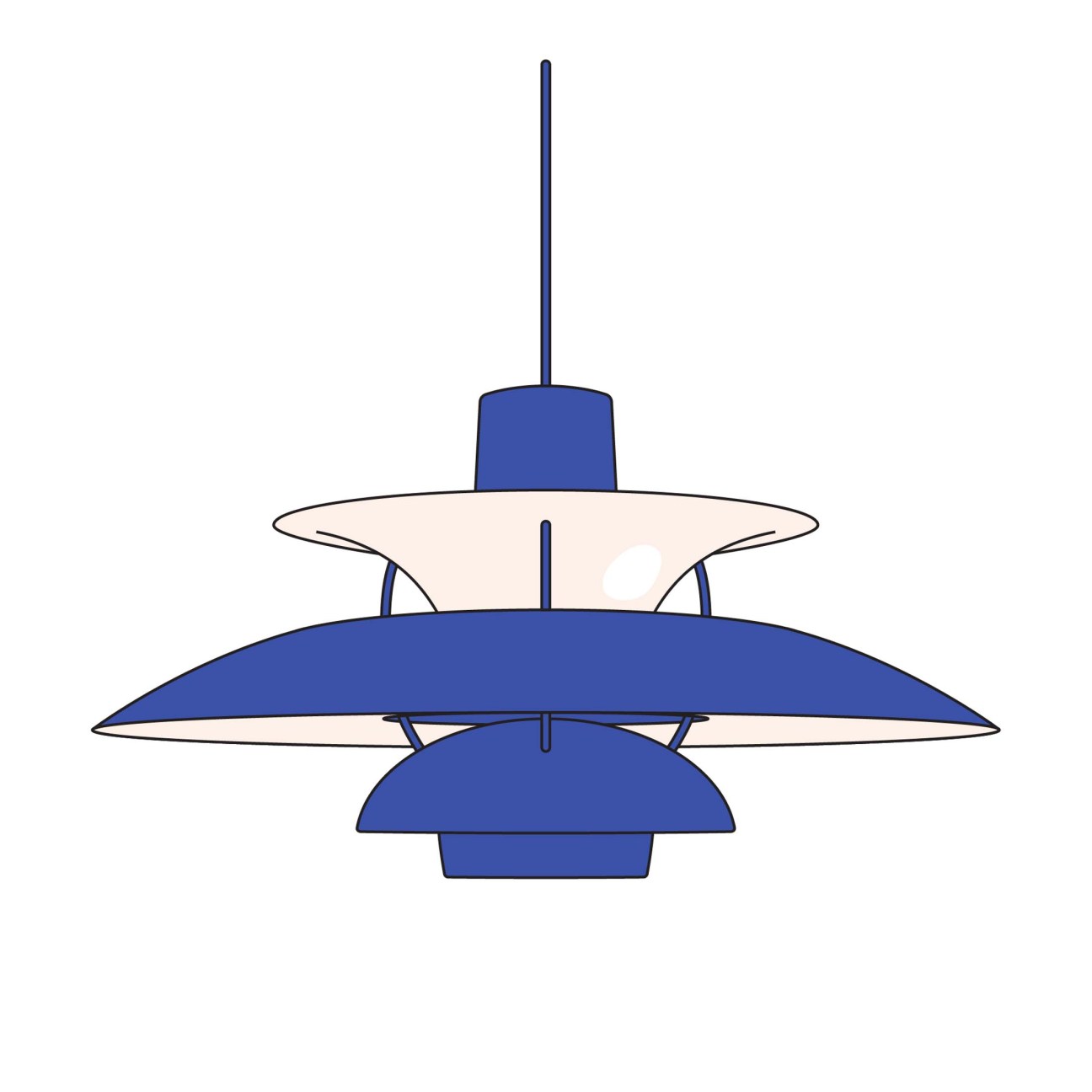

5.

Copenhagen

Denmark

Copenhagen is a design capital in its own right and is best captured by a true icon from the mind of a Danish luminary. The PH5 pendant lamp by Poul Henningsen for light-manufacturing stalwart Louis Poulsen, first produced in 1958, fits the bill.

6.

Melbourne

Australia

Melburnian manufacturer Companion is behind this compact Round-A-Bout gas barbecue, originally from 1975, that consists of a hard-wearing metal shell on three legs. What could be more Australian than firing up the barbie on a scorching summer’s day?

7.

Dakar

Senegal

Designed in 2009 by Birsel+Seck, the Madame Dakar chair is handwoven from plastic threads by the studio’s founders, Paris-born Senegalese Bibi Seck and Ayse Birsel from Turkey. It is an ode to the fishing nets found across Senegal’s capital.

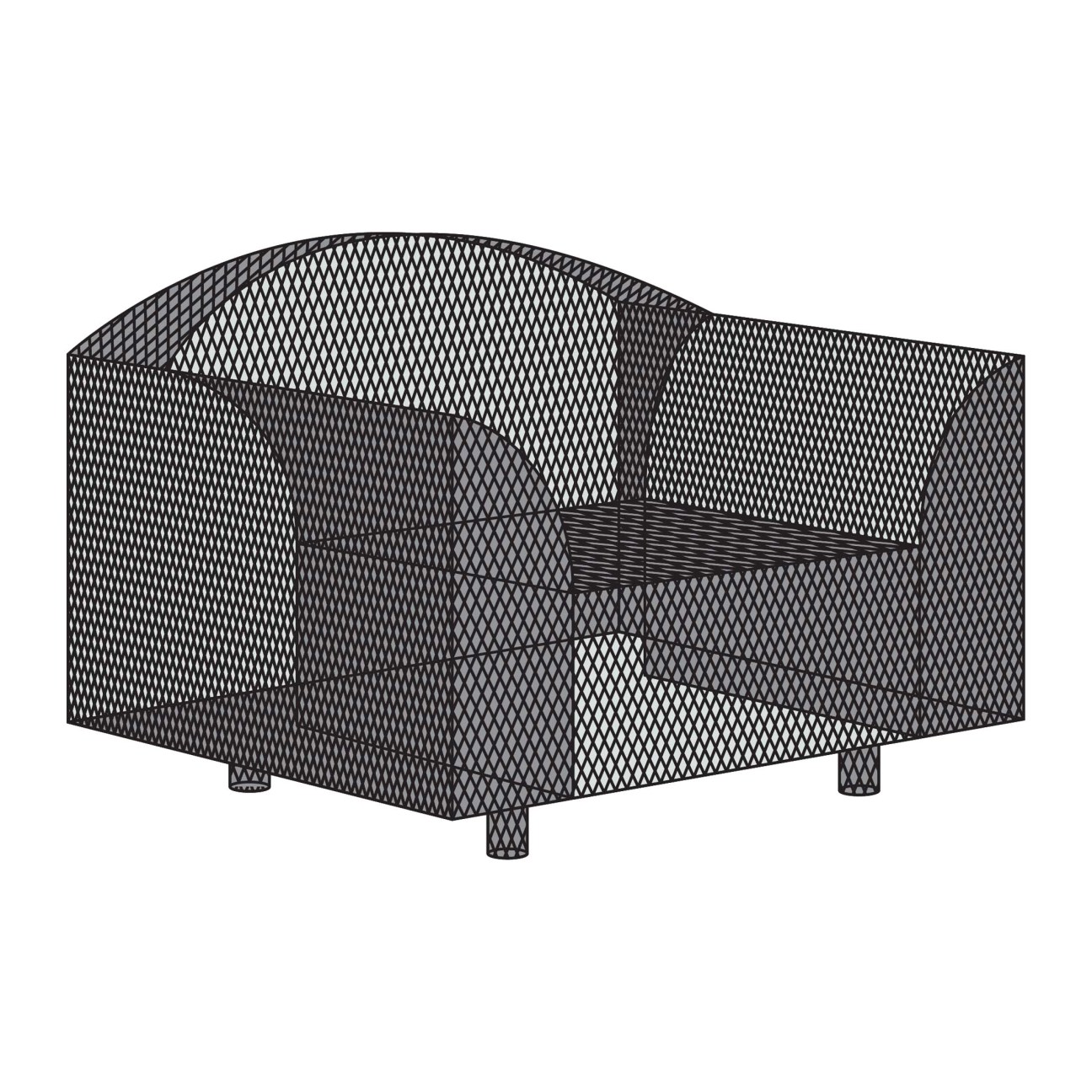

8.

Tokyo

Japan

Shiro Kuramata’s futuristic and sleek How High the Moon armchair from the late 1980s is on the same wavelength as Tokyo. Made from a perforated nickel-plated steel mesh, there is a cool, enigmatic quality to this chair that leaves us wanting more.

9.

Zürich

Switzerland

In the financial capital of Switzerland, time really is money. Since 1944 this Mondaine clock by Hans Hilfiker has been keeping Swiss trains (and residents) on time in the design-forward manner that we have come to associate with Zürich itself.

10.

Mexico City

Mexico

This chair and accompanying stool might be called Barcelona but the set is a resolutely Mexican take on Mies van der Rohe by local architect and designer Luis Barragán, who used it when furnishing Mexico City’s mid-century Casa Prieto López.

The temporary genius of Hyde Park’s summer pavilions

The arrival in June of the Serpentine Pavilion in London’s Hyde Park is a harbinger of the long summer days to come. The temporary structure then becomes a must-visit attraction until it is dismantled in October. What began in 2000 as a project led by the late Zaha Hadid has now been going strong for 25 years, presenting the first UK structure by some of the most interesting names in international architecture.

“We think that it’s important to make the discourse of architecture in the UK more international, to open it up,” says Swiss-born curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries. Crucially, the project champions up-and-coming talent. “We want to give more visibility to younger architects from all continents and it’s interesting to see that it really has an impact on their careers,” he says, adding that because the pavilions never have a door, they are inherently welcoming and inclusive spaces. “People come while walking their dogs or jogging and have a coffee. The pavilion is for everyone so it’s truly a public space.”

This year’s pavilion is the 24th (one year was missed due to the coronavirus pandemic) and will be designed by Bangladeshi architect and educator Marina Tabassum. Titled “A Capsule in Time”, the pavilion is composed of four wooden forms that have a translucent façade. Central to Tabassum’s design is a kinetic element in which one of the forms is able to move, thus changing how the pavilion will be experienced according to the configuration of the space.

“We have been following Marina Tabassum’s work for a long time,” says Obrist. “Often, using sustainable resources, she produces spaces that are almost spiritual.”

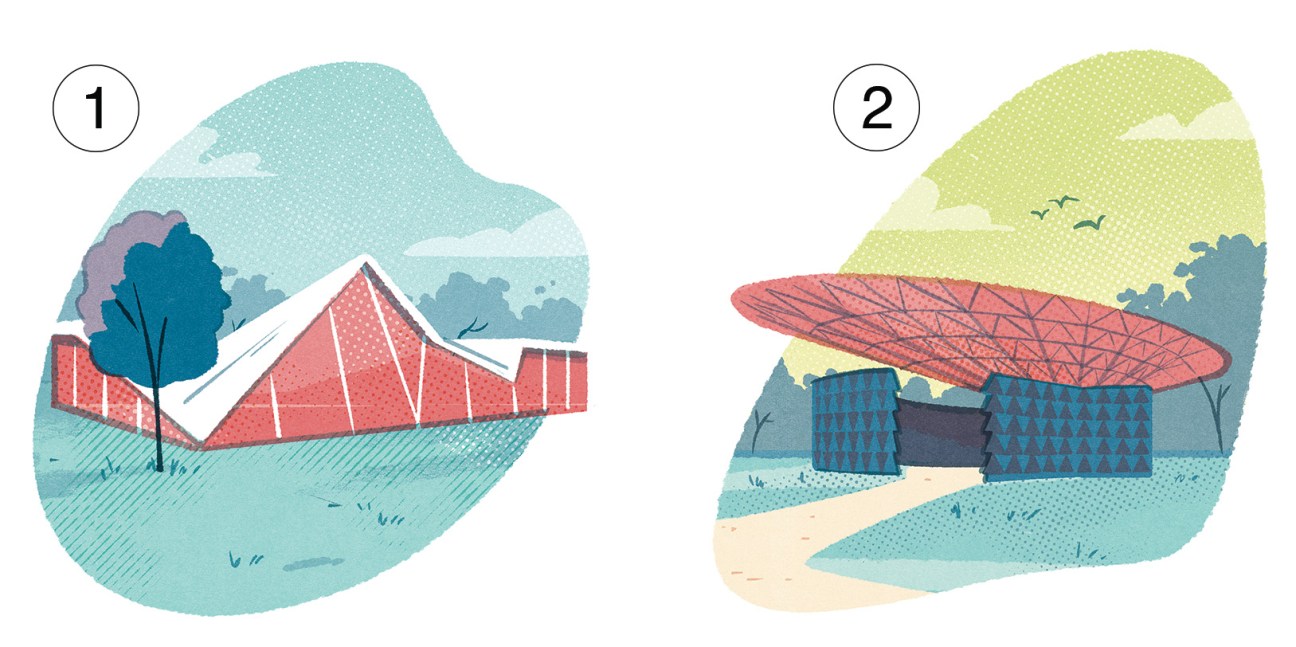

1.

Zaha Hadid, 2000

Hadid designed the inaugural pavilion in 2000, which the gallery commissioned as a one-off project to host a gala to mark its 30th anniversary. It consisted of large white triangular panels supported by a steel frame. Its swooping form proved so popular that the Serpentine managed to keep it open for two months instead of just a day.

2.

Diébédo Francis Kéré, 2017

Inspired by the tree that serves as a central meeting point in his home town of Gando in Burkina Faso, Kéré designed a structure with an expansive roof that mimics a tree’s canopy to offer shelter against the rain and summer heat.

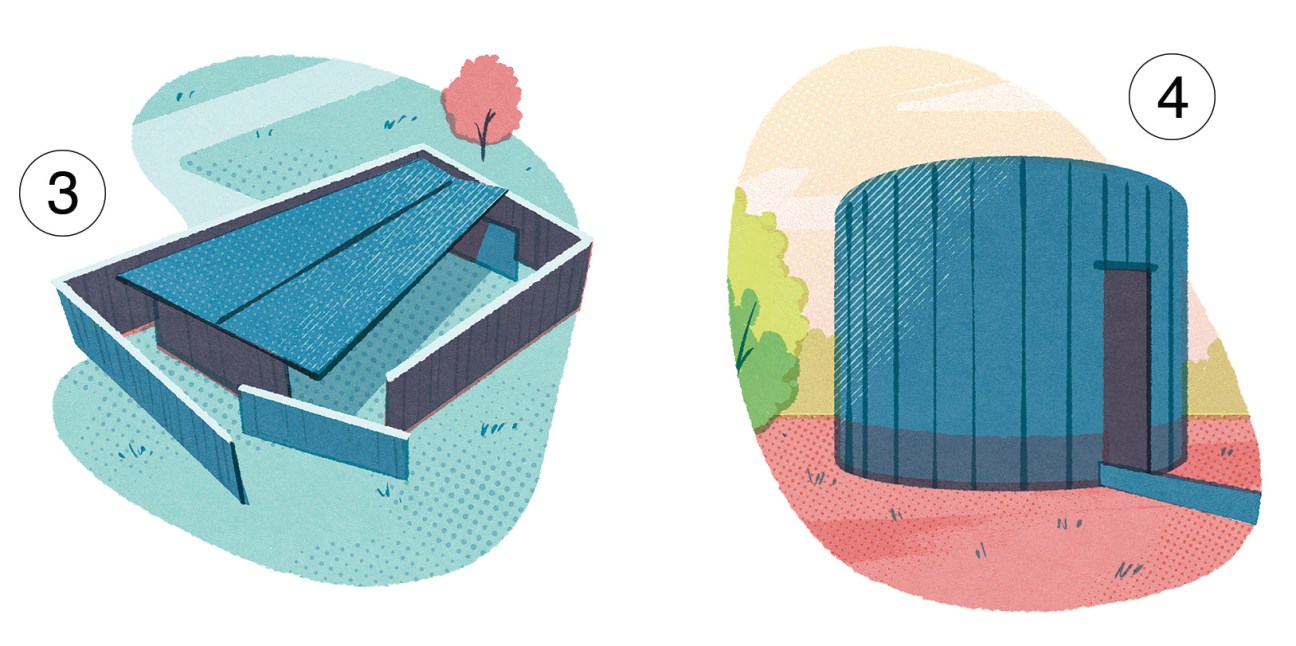

3.

Frida Escobedo, 2018

Escobedo’s pavilion fused elements of Mexican architecture with London references and featured a courtyard enclosed by two rectangular volumes constructed from cement roof tiles. Inside, a shallow water pool and the curving, mirrored roof emphasised the day’s changing light and shadow.

4.

Theaster Gates, 2022

“Black Chapel”, designed by Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates, was inspired by the architectural typologies of everything from the pottery kilns of Stoke-on-Trent to traditional African structures. Conceived as a timber cylinder clad in dark roofing, it was a space for reflection and spiritual communion.

5.

Lina Ghotmeh, 2023

French-Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh (who recently won the competition to revamp the British Museum) called her pavilion “À table” as an ode to the French tradition of sitting down together over a meal to engage in dialogue. The angular, latticework structure responded to the topography of the park and invited visitors to gather at its communal tables.

Milan’s Palazzo Citterio boosts its cultural cachet with a new museum

Milan had to wait a long time for Palazzo Citterio to become a museum – about half a century, in fact. After the Italian Ministry of Culture purchased it in 1972, disagreements, red tape and the death of one of the project’s architects slowed progress towards that goal. But at the end of last year the “Grande Brera” project, uniting the palazzo with the nearby Pinacoteca and Braidense National Library under one cultural umbrella, finally took it over the line.

The museum, which is currently open from Thursday to Sunday every week, was fitted out by Milan- and Bologna-based architect Mario Cucinella. His selection might have had something to do with his impressive work on another cultural institution, the Fondazione Luigi Rovati, on Milan’s Corso Venezia. Cucinella says that he found Palazzo Citterio in perfect condition; one of his jobs was to reinforce the floors to make them sturdy enough to take the expected footfall as part of works that lasted nine months. Mario Cucinella Architects’ hand can be seen in everything from the lighting to the glass cabinets and the two long, curved display tables that are designed to facilitate disabled access, allowing viewers to get close to the works. “There’s so much attention to detail here,” says the architect, speaking from his plant-filled Milan office. “When everything works, no one notices. But if you mess up, everyone does.”

His remit also extended to the entrance hall, which features a sculptural table that serves as a ticket office, information desk and mini-bookshop. The flowing space and integrated seating create a modern, welcoming experience for visitors, while respecting the history of the building.

It presents a striking contrast between old and new, adding to Palazzo Citterio’s architectural mix. The basement, used for temporary exhibitions, is in a 1980s brutalist style, courtesy of UK architect James Stirling. The top floor, another temporary show space with exposed piping, has an industrial look, while the piano nobile, the permanent exhibition floor, feels very much like a section of an 18th-century palazzo. On display are the Jesi and Vitali collections of 20th-century art, which didn’t have the room that they needed at the Pinacoteca. Palazzo Citterio’s 200 or so works include Picassos, Modiglianis and pieces by futurist painter Carlo Carrà.

A Cucinella-designed wooden temple structure, donated to the museum by Salone del Mobile, sits inside an inner courtyard alongside various artistic masterpieces. This courtyard, inspired by a temple in Raphael’s painting “The Marriage of the Virgin”, will eventually be covered by a glass roof. Cucinella says that the aim was to create something contemporary, while also referencing history. It acts as both a functional gathering space and a symbolic meeting point at the heart of the wider Grande Brera complex. “It has become the image of the palazzo,” he says.

palazzocitterio.org

Six spots the Milanese keep quiet about

Milan-based couple Chiara Pino and Riccardo Ganelli left their jobs in fashion to open Bar Nico in 2023 (they were later joined by their friend Nicolò Terraneo). It has since become a hot spot in their home city’s Acquabella neighbourhood, drawing a loyal crowd with its natural wines and Mediterranean small plates. “We’re not doing anything particularly special here,” says Pino when Monocle joins her and her two business partners for lunch. “Milan just didn’t have a natural-wine scene until a couple of years ago.”

That might be true but Bar Nico is flawlessly executed. You’ll find the minimalist space, designed by Milanese practice Sagoma Studio, on the ground floor of a modernist apartment block in a former tyre shop (it was a pasta factory before that). The interior is furnished with Thonet’s bistro chairs, a large aluminium counter and wine shelves. “We serve wines from smaller vineyards in France but also bottles from Italy, Austria and Germany,” says Ganelli, who trained as a sommelier and oversees the selection.

With Bar Nico, Pino, Ganelli and Terraneo are leaning into Milan’s contemporary side. It’s this milieu that the trio introduce to Monocle on a tour of their hometown. As we prepare to set off, the conversation turns to what makes the city tick. “It takes a little effort to fully appreciate Milan because it’s a secretive place,” says Terraneo. Having guides with local knowledge and packed address books full of reliable trattorias and ice-cream shops certainly helps.

Here are the Bar Nico team’s favourite places in the city:

1.

Trattoria del Nuovo Macello

Via Cesare Lombroso 20

“This place brings the heritage of Milanese cuisine up to speed,” says Terraneo, who eats lunch at this trattoria as often as he can. “There’s one man who always calls the restaurant to place his order 10 minutes before the kitchen closes so that it’s ready when he arrives.”

trattoriadelnuovomacello.it

2.

Chiesa di Santa Maria Annunciata

Via Neera 24

In this church in the south of Milan you’ll find US minimalist artist Dan Flavin’s final installation. He completed its design two days before he died in 1996. Come here for a moment of quiet contemplation.

parrocchiachiesarossa.net

3.

Pavé

Via Cadore 30 and Via Cesare Battisti 21

At its two locations in the city, Pavé serves the best artisanal ice cream. Pino’s rates the almond and amarena cherry flavour highly.

pavemilano.com

4.

Massari Giovanni Fiorista

Piazza Giuseppe Grandi 24

Florist Giovanni Massari sells bouquets with dramatic flair. “I love to drop by and catch up with him,” says Pino, who regularly picks up flowers here.

+39 02 7012 6975

5.

Cinema Godard at Fondazione Prada

Largo Isarco 2

Movie nights don’t get much more chic than this. The programme at Fondazione Prada’s in-house cinema ranges from classics to buzz-worthy new releases.

fondazioneprada.org

6.

Peck

Via Spadari 9 and Via Tommaso Salvini 3

This small deli chain is a Milanese institution. With two locations in the city (and an outpost in Forte dei Marmi on the Tuscan coast), it has been a reliable one-stop shop for the finest cheeses, cold cuts, wines and pasta since it first opened in 1883.

peck.it

How to search for the new in Milan, a city filled with old wonders

Seeking out artisans and designers is the most curious part of my job as Konfekt’s editor. I constantly overturn teacups and even chairs (mid-meal) to find the marque of a little-known manufacturer or bolt off on unscheduled trips to ateliers and factories on what’s meant to be a beach holiday – much to the chagrin of my family. Happenstance is behind many of the stories and people in the magazine. They are often elusive, discreet discoveries that we coax into print.

During the week of Salone del Mobile the energy changes – ideas come in shoals, shimmering in the April light. Milan jostles and teems with inspiration; so much so that it can take a certain amount of restraint – and strategy – to simply walk across town. After months of cold days spent inside, the city’s bosky streets become a forum to reflect on space, form, beauty and the way we live.

A stroll through Brera during the fair feels like a carnival of sorts but also reminds you that beauty and innovation is a part of Milan’s tradition as a city. It’s this perspective that gives the flurry of launches such perspective – the old fabric of the city holds up the new. It asks us, “Will this pass the test of time?”

Navigating Milan at this time of year is about making time for the last of the carciofi and the first of the fiori di zucca. It’s about savouring the magnolias in bloom in the Piazza Tommaseo. Between appointments, I like to nip into Da Giacomo, near Porta Vittoria, for a plate of vongole or rest weary legs at Fioraio Bianchi Caffè, a florist that also serves unrivalled ravioli.

I try not to leave Milan without having a saffron-infused risotto in the café at the mid-century Villa Necchi, where mint-rattan is the order of the day and fleets of waiters hover. Built by architect Piero Portaluppi in the early 1930s (and made famous by the Luca Guadagnino film I am Love), the marble floors and damask walls speak of the way that tradition dances with the new in the city, and the sense that beautiful things – crafted to last – will continue to inspire and spark curiosity long after they were deemed new.

Spots in Milan

Here’s where you’ll find Konfekt’s editors scribbling in notebooks – possibly clutching a negroni.

Galleria Rossana Orlandi

Salone’s grand dame champions new talent in her verdant space on Via Matteo Bandello.

rossanaorlandi.com

Nilufar

Drop in to founder Nina Yashar’s first gallery space on Via della Spiga to discover a host of new talent experimenting with colour, shape and function. (Or head to her larger location for more expansive projects.)

nilufar.com

Alcova

This “itinerant platform for freethinking design” has taken over Villa Borsani, a 1940s-era 800 sq m residence built by Osvaldo Borsani, and uses it to dazzling effect to display installations and pieces.

alcova.xyz

Dimoregallery

Founded by Emiliano Salci and Britt Moran, better known as Dimorestudio, this gallery offers a textured raft of ideas and collaborations in a 700 sq m space near Milan’s Centrale train station.

dimoregallery.com

Three makers providing a stepping stone to working with marble

“Our participation [in Milan Design Week] has a romantic origin,” says Eleni Petaloti, one half of New York and Athens-based Objects of Common Interest. “I always complain about us Greeks not being able to be ambitious together. So it was very important for me, psychologically, to be a part of this.” The Thessaloniki-born architect and designer, who runs the studio with her husband, Leonidas Trampoukis, is talking about the pair’s project in Milan this year at Alcova’s Pasino Glasshouses, entitled “Soft Horizons”. Featuring Greek marble from seven different companies with quarries around the country, from Athens to Thassos, the immersive installation features nine marble sculptures made by the designers using off-cuts, as well as some seating installations.

Petaloti jokes that Italy has always been good at selling itself, from furniture to olive oil, whereas Greece has been “very introverted”. Which is why Objects of Common Interest jumped at the chance to be involved in a collaboration with the Greek Marble Association. Greece has been realising that its stone trade, which can trace its history back to the Parthenon, has something to say. In fact, at the end of 2022 the association, with the backing of Enterprise Greece investment entity, created a brand name to help bring it to the world: “Greek Marble: Then. Now. Forever”.

The Alcova installation is an important step. “We haven’t worked on our branding and storytelling [until now],” says Irini Papagiannouli, the third-generation family member of John Papagiannoulis Bros, one of the companies that has supplied stone this year. “But the history is there.” Irini has been instrumental in helping to turn the Design Week show into a reality.

Objects of Common Interest’s Petaloti admits that she didn’t always like marble growing up. “It was everywhere,” she says. “A plaza, a church, people’s houses if they wanted to be fancy in the 1980s and 1990s.” But she has come to fall in love with the fact that it is part of Greece’s “cultural DNA”, witnessing it first-hand working with a seventh-generation marble maker from Tinos. In fact, Objects of Common Interest’s first design, the Bent Stool from 2016, was made from the material. Nonetheless, the concept behind “Soft Horizons” has been to get away from the imposing and sometimes overwhelming way in which marble is often presented and instead go for something “ethereal”, as Petaloti puts it.

The “Soft Horizons” objects, which the studio calls totems due to the way they are assembled, each use several different pieces of marble that have names as diverse as Thassos Silver stream and Arabescato Kasta, and sit on top of a water pond, while two of the pieces will react to motion and move as a visitor approaches (“It’s a comment on how marble and humans have the same link to nature,” says Petaloti). A red, disc-like speaker from New York’s Oda hangs above the installation, playing sounds from the production process. While all the focus has been on the Alcova show, Objects of Common Interest say that this is the starting point for taking Greek marble around the world. “This isn’t about impressing because it doesn’t have that scale,” adds the designer. “Instead, it’s a personal dialogue with a material.”

objectsofcommoninterest.com

Torque of the town: Luxury car brands swerve into the sector of high-end fashion

Cars are everywhere in Milan during Salone del Mobile (except in the form of taxis when you need them the most). On Corso Venezia are the shops of Bentley Home and Bugatti Home, where customers can buy furniture that makes living rooms feel like the inside of a sports car. Around Cassina’s showroom on Via Durini circulates a Lancia Ypsilon with sapphire-blue interiors courtesy of the Italian furniture titan. Audi is presenting its latest models in a Studio Drift-designed pavilion in Piazza Quadrilatero, one of the city’s grandest courtyards. What we’re seeing right now is every kind of crossover: furniture designed by car brands, cars designed by furniture brands, and just cars on display in the ritziest corners of Milan. Meanwhile, the Geneva International Motor Show – once the industry’s premier convention – has cancelled this year’s edition due to lack of interest from manufacturers. It seems that the automotive sector has backed out of its own jamborees, rolled up in Milan in time for Design Week and parked.

The growing presence of car brands in Milan partly follows the example set by luxury fashion, which has also expanded its footprint at Fuorisalone. This is evident in the trajectory of Luxury Living Group, a Forlì-based manufacturer that first introduced a licensed furniture collection with Fendi in 1987. Today the Italian firm produces furniture lines for the likes of Dolce & Gabbana and Versace, as well as Bentley and Bugatti. “Up until a few years ago, we were the rare birds doing this,” says Andrea Gentilini, CEO of Luxury Living. “Now most luxury brands have started on the same journey.”

Gentilini lists off labels such as Hermès, Bottega Veneta and Gucci, which consistently present designs at Salone that give traditional furniture firms a run for their money. Cars, however, have a particular claim on being in the world capital of design. In the 20th century, when furniture started being industrially produced, many designers drew inspiration – as well as technical components – directly from the automotive sector. In one famous example, Italian designers Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni ordered a US-made car headlight, connected it to an electric cord and perched it on top of a steel pole. Launched in 1962, the Toio remains one of the bestselling floor lamps made by Flos. In 1981 a young architect called Ron Arad found the leather seat of a Rover P6 in a London junkyard, mounted it on a steel frame and created the chair that launched his career.

Tongue in cheek or not, many modernist designers admired the beauty and efficiency of car design and manufacturing, and saw it as an ideal to be adopted in their field. Architects have also always jumped on the chance to design some wheels. In 1936, Le Corbusier took part in an open design competition to create an affordable French car. His submission was the Voiture Minimum, a strange design with a round profile and flat sides. It anticipated the outlines of cars that entered production decades later.

In 1978, Italian designers Elio Fiorucci, Ettore Sottsass and Andrea Brianzi spruced up an Alfa Romeo Giulietta with denim-coloured Pirelli wheels and an interior entirely covered in green fur and mustard-yellow velvet. The one-off Alfa Romeo Punk was widely panned by critics at the Geneva vehicular salon, who found it bizarre. (With hindsight, perhaps the Swiss should have been more welcoming to frivolous and left-field ideas.)

What makes today’s car-furniture crossovers different is that the automotive brands are willing participants in them. While the Castiglioni brothers didn’t ask anyone before they repurposed some spare parts, this time around everybody is in on the action. “This collaboration is a two-way street,” says Giovanni del Vecchio, CEO of Giorgetti. At the furniture label’s showroom on Milan’s Via della Spiga, visitors can admire the Giorgetti Maserati edition, an armchair and pouf inspired by the sports car’s design language (and a permanent addition to the brand’s collection), as well as the Maserati Giorgetti edition, a one-off Grecale Folgore (an all-electric SUV) with interiors inspired by the design house. More than borrowing technical parts or techniques, the collaborators emphasised shared values. “Both of these brands represent everything that is beautiful and well crafted in Italy,” says Del Vecchio. “Each is in its own sector but when they talk to each other, they speak the same language.”

These tête-à-têtes have created furniture collections with their aesthetics rooted in the automotive world. Giorgetti’s Lorelei armchair and the Teti pouf have soft seats encased in outer shells that are upholstered either in leather or lacquered in gradient hues – finishes familiar from high-end cars. There are also no hard corners. “It’s as though the design went through an air tunnel,” says Del Vecchio.

The Bentley and Bugatti collections created by Luxury Living are similarly subtle, with sycamore veneer sofas that nod to the dashboards of Bentley cars, or a dining chair stitched with leather as supple as a Bugatti’s seat. Gentilini explains that creating high-end furniture is a far more sensitive and time-consuming endeavour than typical branded collaborations, which often involve little more than slapping on a logo. “If I would get a Ferrari project, it’s not like I would make a chair the shape of a prancing horse,” he says. “This is about interpreting the values, codes and language of the brand and translating it into something that you can have in your home.”

It remains to be seen whether people like their cars to feel like living rooms and their living rooms to feel like their cars. Yet the collaborations are a reminder that the two sectors have a common history and heritage, even though only one can go from zero to 100.

April showers: How one studio has transformed a former pool into a design showcase

“I came here for an architecture exhibition at the end of last year when it was open for a few days and asked about renting the space,” says Francesco Palù, co-founder of Milan’s 6:AM Glassworks. That makes the process of turning this venue into the brand’s Design Week site sound much easier than it was. monocle meets Palù for a preview of 6:AM Glassworks’ showcase of its eclectic work to date in the basement of the rationalist Cozzi swimming pool in Milan. We’re at the entrance of its public washrooms, which were inaugurated in the 1950s and have long been out of use. Architects, engineers and administrators are gathered around as someone drills into the ceiling to check that the lights that the brand plans to hang will hold.

Established in 2018, 6:AM has made a name for itself by taking the traditional skills of Murano’s glassmakers and translating them into contemporary design pieces. Palù, who is from Parma, met the brand’s Venetian co-founder Edoardo Pandolfo when they worked for architect Andrea Caputo. After they both left, Palù needed help sourcing glass for a project for Locatelli Partners and asked his friend to work his Venetian contacts – and the idea for 6:AM was born.

The Cozzi show, entitled Two-Fold Silence, is 6:AM’s first solo exhibition (the practice was part of a group show at Dropcity last year) and features lighting, furniture, objects and site-specific installations. “This is all about giving an idea of a story and the direction that we want to go,” says Pandolfo of the curation and the decision to use the swimming-pool space.

The entrance to the washrooms, featuring a sea-scene mosaic and a ceiling border of seahorses, will be installed with dark curtains and a large ceiling light featuring a series of Murano-made cubes inspired by Bauhaus Atrax lights that the pair saw in Berlin. One or two objects will be placed in each of the 17 showers, from the Sistema wall light featuring stainless steel and appliqué cast-glass to the 5/10/12 table in coloured glass. “It’ll be a bit of a labyrinth where you can get lost,” says Pandolfo.

With low lighting, a soundscape of Mediterranean sounds by Milan’s Invernomuto and a whiff of palo santo in the air, Two-Fold Silence promises to be one of the highlights of Fuorisalone. “As an emerging brand, we have to do cool things,” says Pandolfo.

The Japanese principle influencing designers with an emphasis on peace and presence

Remember when the design world fell for feng shui? Its proliferation in the West followed Richard Nixon’s state visit to China in 1972 and it didn’t take long for people to want to apply its teachings to their immediate surroundings. After all, who doesn’t want a sprinkle of harmony in their home? Since then, various design philosophies for our domestic environments have caught our attention, from Japan’s wabi sabi to Denmark’s hygge – as we all search for ways to make our homes more comfortable places to be.

At their core, these philosophies tend to respond to something that all humans need, wherever we live: access to natural light and warm, tactile materials, such as timber. Yes, there might be more of an emphasis on cosy throws and candles here or minimalism there but these particular interiors-shaping modes of thought have caught on because they speak to a desire to make our homes a calming sanctuary. So it’s not surprising that there has been a warm response to interior designer Yoko Kloeden’s novel approach, which incorporates the Japanese principle of yugen.

London-based Kloeden came to design later in life, retraining as an interior designer after years in corporate work, intense international travel and many nights spent amid bland hotel interiors. Her wish, as a designer, was to distil the particular feeling that she had experienced while seeking shade in the temples of Kyoto, her hometown.

There, she felt a sense of tranquillity that she struggled to translate into words, until she alighted on yugen, which means, roughly, a deep sense of presence and peace found in the subtle beauty of life.

But how to render this ephemeral, fleeting feeling into real-world interiors? Kloeden set out to distil five principles that help her to create balanced, calm environments for her harried clients: hikari (light), nagame (view), ma (space), shizen (nature) and taru o shiru (less is more), each one guiding her interior design choices to cultivate harmony and celebrate simplicity. “Homes should be where you can leave all your baggage at the door, completely relax and rejuvenate for the next day, without having to go to the actual temple to find that feeling,” the designer tells Monocle.

For Kloeden, senses beyond the visual, such as touch and smell, are important – as is remaining aware that the materials we come in contact with can affect how we feel. “Be on the lookout for something organic and natural, and maybe a little bit imperfect, such as timber – it smells, sounds and feels nice,” she advises. Things that are not overly polished and bear the traces of the work and care taken to make them help us to reconnect to those who came before us and to feel a little more grounded. It’s a thought that’s shared by Signe Bindslev Henriksen and Peter Bundgaard Rützou, co-founders of design studio Space Copenhagen, who work on everything from private homes to hotels and restaurants, and whose approach taps into both Scandinavian and Japanese design traditions.

“We live in a time when things are moving so fast,” says Bindslev Henriksen. “There’s a humanist aspect to both Danish and Japanese design, which I think deeply resonates with all people; there’s a feeling that somebody cared, that somebody spent time thinking and making that detail in wood, for instance.” A few decades ago, when we were living in a more optimistic age, we were designing with new materials, adds Bundgaard Rützou. And we might do so yet again. “There is an uncertainty that defines our times and it seems that we have this longing to reach for something that feels ancient,” he says. “But it could pivot; in 10 years’ time, we might be all about a material that doesn’t even exist yet.”

In the meantime, if overhauling your entire home seems like one task too many, both Kloeden and Space Copenhagen urge you to start small. Dump the clutter, light a candle, buy a plant, embrace the imperfections and be mindful of the kind of furniture you bring into your home. As someone somewhere rightly pointed out, no doubt while stealthily shuffling their own ephemera into the recycling bin, “less is more”.

About the writer

Zhuravlyova is a journalist based in London. She has written about homes from postmodern Italian masterpieces to British prefab structures.

Toying with convention in the House of Toogood

If you’ve been on the design-fair circuit over the past 12 months, there’s a strong likelihood that you have encountered the work of Faye Toogood. Whether it’s being named guest of honour at the Stockholm Furniture Fair and designer of the year at Paris’s Maison & Objet, working with Italian manufacturers including Cc-Tapis, Tacchini and Poltrona Frau, collaborating on an installation for Danish brand Frama’s Copenhagen flagship or working on the Toogood fashion line with her sister Erica, the British designer has, of late, been unavoidable. “Sorry about that,” Toogood tells Monocle when we meet at her London studio, where she heads up a team of 25. “Something seems to have clicked and it’s amazing to be riding that wave.”

As we sit down, Toogood posits that this surge in popularity is linked to her work’s emotive content. “I’ve been putting more of myself into my work without worrying about how it sits in the context of design,” she says. “I’m working intuitively and allowing space for experimentation.” When she founded her studio in 2008, Toogood came from a background in fine art and sculpture, and had been working as a stylist at The World of Interiors for eight years. “I didn’t set out to be a designer, so I started quite apologetically,” she adds. “Because I was on the fringes of design, art and fashion, I was seen as not being serious, as dabbling. But I’ve formed a place for myself on these fringes.”

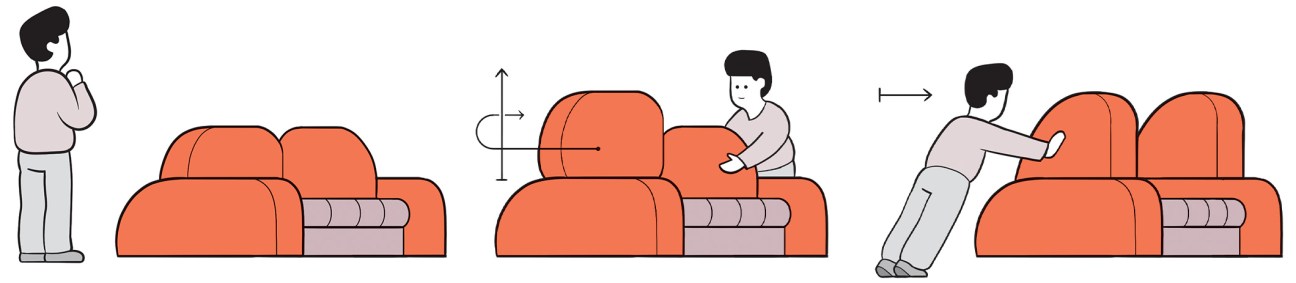

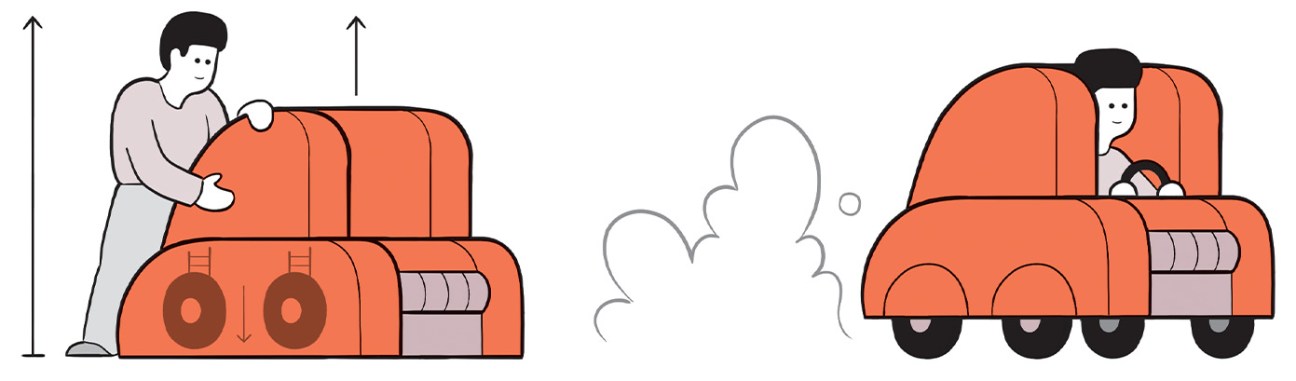

Now firmly established in the industry, Toogood is regularly tapped by manufacturers looking to work with modern designers. When we meet, she has just returned from Nagoya, where she spent a week hand-painting pots with roses for Japanese ceramics company Noritake. The resulting collection of limited-edition pieces, called Rose, will be shown at Milan Design Week this year, with scaled-up production of the pieces slated for 2026. Toogood is also returning to Milan this April to launch her second line of furniture with Brianza-based manufacturer Tacchini, after the success of her Cosmic collection of a sofa, shelves, mirrors and pendant lights, unveiled at last year’s fair. Titled Bread and Butter, the new collaboration revolves around a modular sofa rendered in a soft, light yellow leather. “I like looking to food for inspiration; it’s a smack of reality,” she says. “It’s about rejoicing in the everyday, in the food I grew up with, in the food I give to my children.”

As a designer, Toogood infuses her work with a tenderness rarely spoken about in the design industry. Her Roly Poly chair’s voluptuous shape draws inspiration from her personal experience of pregnancy and motherhood. To sit in her Gummy armchair is to receive an upholstered hug. “I’m quite a tactile person, an emotional person,” she says. “I often feel like a thermometer because I’m hypersensitive to the energy of what’s going on around me. A lot of my designs are autobiographical but they’re also out of genuine care for others.”

According to Toogood, this need to put society over the self is the reason she became a designer and not an artist – albeit in her own experimental manner. Every new project often begins with a word, a song title or even a poem, providing a starting point to shape the identity of each piece. She makes early miniature models using materials such as sheets of aluminium or pieces of clay, allowing her to play around and see what comes out. And during the editing stages, Toogood will begin to search for tension between the soft and the hard, the precious and the raw, the industrial and the handmade, before finding a balance. When it comes to the actual production of these pieces, Toogood mostly works with carpenters and upholsterers based in the UK.

It’s a far cry from intricately drawn sketches or computer-assisted design – but her divergent method for design is now at a stage in which it is being welcomed by the very industry that sets the norms. “It’s my role to break down boundaries, agitate, open doors, question, blur,” says Toogood. “I might not have achieved everything I wanted to achieve but I’ve opened up the conversation through my own experimentation. I’ve helped to widen the lens of what design is. For that, I’m proud.”

As Monocle leaves the serenity of House of Toogood, the designer changes into a pair of paint-splattered overalls to tackle a mobile and table. For Toogood, there’s no time to rest but always plenty of time to play.

The CV

1977

Born in the UK

1998

Graduates with an art history degree from the University of Bristol

1999-2007

Works as decoration editor for The World of Interiors

2008

Founds her studio

2010

Designs Spade chair, stool and bar stool

2012

Launches Toogood clothing with her sister, Erica

2014

Designs the Roly Poly chair

2019

Collaborates with Cc-Tapis on the Doodles collection

2021

Creates the Puffy ottoman for Hem

2022

Phaidon publishes Faye Toogood: Drawing, Material, Sculpture, Landscape

2024

Releases Gummy armchair and collaborates with Vaarnii, Cc-Tapis, Tacchini and Poltrona Frau

2025

Named Maison & Objet designer of the year and Stockholm Furniture Fair guest of honour. Launches collaborations with Tacchini and Noritake