Jakarta rising: Inside the creative renaissance of a city on the brink

Despite congestion, flooding and its looming replacement as Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta is buzzing with new energy. Discover the creatives, chefs and designers breathing life into Southeast Asia’s largest metropolis.

Traffic-clogged, slowly sinking and the centre of anti-government protests, Jakarta is scheduled to be replaced by Nusantara as Indonesia’s capital city in the coming years. But the streets of Southeast Asia’s largest metropolis – home to more than 11.4 million people – are still brimming with life, thanks in part to the efforts of a new generation of creatives and entrepreneurs who are re-embracing their roots.

It’s midday on a Friday in South Jakarta and Siti Soraya Cassandra and her husband, Dhira, have a pond to clean. “There wasn’t any permaculture in this city so we decided to make it,” she says. The couple’s company, Kebun Kumara, is regreening the Indonesian capital, one urban forest or edible garden at a time. In a few months they expect to finish work on the expansive Taman Kota Peruri gardens, their largest project so far.

There’s no shortage of residents to unite with the outdoors here. Following Indonesia’s independence in 1945, Jakarta experienced a decades-long boom and became Southeast Asia’s most populous hub. More than 30 million people now call the greater Jakarta area home but green spaces make up just 4.65 per cent of the city, with an average of a paltry 7.1 sq m of green open space per capita. Even fellow megacity Bangkok has 7.6 sq m per person, while Singapore boasts 47 per cent green coverage.

With architecture firm ARD Design, Kebun Kumara is transforming a 1.08-hectare patch of disused, state-owned land into a public park full of plants from the region, such as scholar trees, lemon basil and pandan. Cassandra hopes that this will be the first of more large-scale projects. “Everybody in Indonesia gravitates towards Jakarta,” she says. “It’s up to us, the people who live here, to make it as resilient as possible.”

In recent months, Jakarta has been the centre of anti-government protests. It is often labelled “the fastest-sinking city in the world”, an unfortunate sobriquet gained thanks to its rapid growth, excessive groundwater extraction and frequent flooding. Coupled with its reputation for gridlocked traffic and the lingering question over its status as Indonesia’s capital, all of this has meant that more people are leaving Jakarta than migrating to it. Last year, for every person who moved here, almost three left. Even so, many young creatives and entrepreneurs are staying or returning home to put down roots. Monocle has come here to spend a weekend with this ambitious cohort of people who are steering the city’s cultural renaissance.

A 10km drive southwest of Kota Peruri brings us to another park, Taman Manyar. This slice of Jakartan suburbia is where Andra Matin, one of Indonesia’s most revered architects, lives and works. For years, Matin has been acquiring the buildings surrounding the park to create a small creative complex. This is nothing new for the architect, who has long sought to transform his home city for the better. “I’ll stay in Jakarta as long as possible to see how it changes because I have hope that it will become a good city in the future,” he tells Monocle.

We pop into Kopimanyar, a café that Matin set up for his workers and visiting design pilgrims. “My staff members like coffee,” he says. “Also, having my kopi [coffee], my house and my office in one place is useful.” Milky brews sweetened with palm sugar in hand, we walk through the building, which transitions from a café into a series of meeting rooms and exhibition spaces. Today it’s calm but in October it will host Bintaro Design District, a biennale that Matin co-founded in 2018 to galvanise the local scene. “Many architects and designers live in the area,” he says. “There were so many art events in Indonesia but none for design. Our festival keeps getting bigger.”

Matin’s house overlooks the park. His work is renowned for its integration of the indoors and outdoors, and his peaceful home exemplifies that approach. Made from exposed concrete and reclaimed ironwood, the structure cleverly allows in plenty of natural light. The only movement comes from dozens of luxuriating cats – Matin and his wife have adopted more than 80 of them and they freely roam the grounds – in between siestas in the park’s sleek, Matin-designed cat houses.

Jakarta might be hard to traverse geographically but it’s a joy to navigate socially. Befriend one person and it’s likely to lead to introductions to everyone they know. Next, we visit I&L Residence, which Matin designed for his friend Henricus Linggawidjaja. The latter is the owner of Artnivora design studio and helps to oversee Art Jakarta, one of Southeast Asia’s biggest art fairs. “This city’s creativity has been growing for a long time now,” says Linggawidjaja. He suggests that we visit the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Museum Macan), which opened in 2017. We tell him that it happens to be where we’re heading tonight – but first we have an appointment with Winfred Hutabarat and Michael Wijono, co-founders of The Union Group, Jakarta’s leading hospitality business. “Ah,” says Linggawidjaja. “[Hutabarat’s] house was designed by Andra too.”

Started in 2008 with a single bistro, the Union Group now encompasses 28 venues. We meet Hutabarat and Wijono over wine and satay skewers at the Cork & Screw Country Club, which Matin also designed. The hospitality group was created with the aim of bringing global cuisines to Jakarta but now it’s opening its first Indonesian restaurant. “The market has matured and locals want local food,” says Wijono. Hutabarat adds that it’s high time the country’s neighbours got to know about Jakarta too. “Indonesians always visit places such as Singapore, Bangkok or Hong Kong,” he says. “It should be a two-way exchange.”

Evening congestion in Jakarta makes fashionable lateness commonplace but our drinks push our tight schedule to its limits. Luckily, Hutabarat is on his way to Museum Macan too and offers us a lift. “There are pockets of great things in this city,” he says as we sit in traffic. “Museum Macan is our window to contemporary art.” Tonight is the opening of Japanese artist Kei Imazu’s first solo exhibition in Indonesia, The Sea Is Barely Wrinkled. The show was inspired by the coast and Jakarta’s history of continuous reinvention – first as Sunda Kelapa and Jayakarta, then as Dutch Batavia, until independence in 1945.

When we arrive, Hutabarat finds his partner, Jun Tirtadji, who runs gallery ROH Projects. “When we started we were pushing a snowball up a hill,” says Tirtadji. “Now it’s rolling downhill. It feels as though Jakarta’s art story has only just begun.” He helps us to find Amalia Wirjono, Museum Macan’s head of development. “This museum’s demographic is young,” she says, as she points out works from the permanent collection. Yayoi Kusama installations and Keith Haring paintings are displayed alongside pieces by homegrown pioneers such as Raden Saleh. “We’re offering something here that Jakartans once had to travel outside of Indonesia to find,” says Wirjono. She introduces us to her sister, Cynthia, who we previously arranged to meet the following day. “Museum Macan is probably our only museum with world-class art,” she says. “But we’ll talk about it more tomorrow.”

Saturday morning starts at Space Available, a community space, café and shop in Kemang that recently relocated here from Bali. Kemang’s lively atmosphere and leafy streets once made it Jakarta’s go-to neighbourhood for expats. However, various misfortunes – ranging from flash-flooding to upticks in crime, followed by the hammer blow of the coronavirus pandemic – caused its star to fade. Space Available’s arrival was a vote of confidence in the area’s revival. The building was originally designed by – who else? – Matin. Sidarta & Sandjaja, a firm helmed by two Matin alumni, has since turned it into Space Available’s striking HQ, whose façade is mottled with cut-outs shaped like fruits of the indigenous kemang tree.

“Space Available is a community centre for self-care,” says music director Aradea Barandana, as his dog, Zissou, patters towards the meditation room. The brand also recycles waste by turning it into homeware and clothing. “We’re here for people who think about the environment and want to make this city a better place.”

Barandana offers to take us to our next appointment, so Monocle – and Zissou – hop in his car for the short drive to fragrance brand Oaken’s HQ. The company is launching two new scents tonight and rain has prompted a last-minute relocation of the DJ decks. “It’ll be fine,” says Cynthia, laughing, as water trickles from a tear in the gazebo.

Oaken’s office above its shopfront serves as a modest home for what is now one of the region’s most exciting fragrance companies, whose soaps can be found in Ombé cafés and 25Hours hotels. In a corner of the shop sits a perfumer’s organ that’s tightly packed with samples. It’s here that Chris Kerrigan, Cynthia’s husband and Oaken’s co-founder, creates the brand’s scents. These make use of Indonesian ingredients, such as patchouli and sandalwood, and are often inspired by local places.

For Chicago-born Kerrigan, Oaken is the culmination of his 20-year love affair with Jakarta. “If you have a vision and want something that you’re not experiencing, you can make it happen in this city,” he says. For Cynthia, the brand is part of her lifelong quest to put the spotlight on her home city. “Everybody comes together to help each other here,” she says. “It’s a close-knit creative community.”

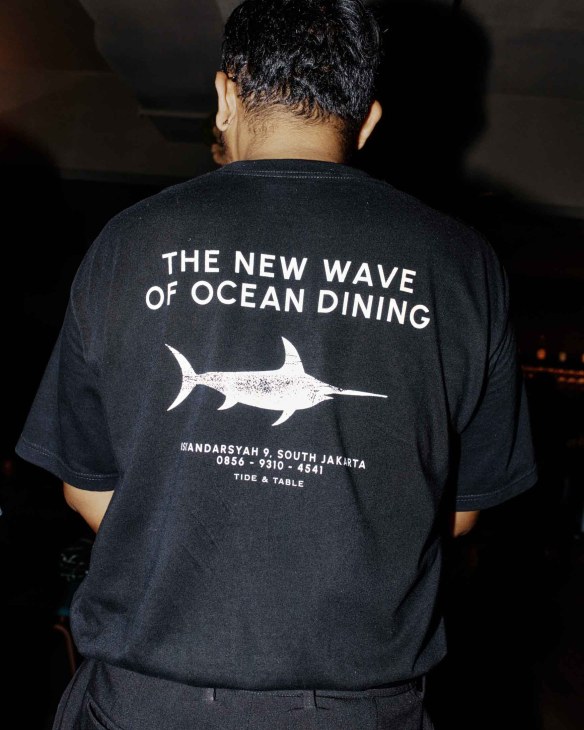

As night falls, we head to seafood restaurant Tide & Table. Its chef, Theodore Darrel, has recently returned home after years in Switzerland and then Bali. “The food scene in Jakarta is ramping up,” he says. “Five years ago a place like this couldn’t have existed.” Nextdoor, Kurasu Kissaten is pumping. At this Japanese-inspired listening bar, more people are drinking coffee than sipping cocktails. “About 90 per cent of the population here is Muslim but everybody still needs somewhere to go for a good vibe on a Saturday night,” says Michael Djuita, whose hospitality venture 20wol funds Kurasu Kissaten. Djuita founded 20WOL after returning to Jakarta from Melbourne in 2014. “People were seeing what was trending abroad and started demanding a better product here,” he says. “That’s where we came in.”

The fund has now supported more than a dozen spots, including Kurasu Kissaten’s sister venue, Hats. There’s a late-night ice-creamery at the front of the latter but step inside and you’ll find young Jakartans knocking back shots. Djuita’s next goal is to attract more tourists and counter Jakarta’s reputation as a staid regional hub for business, not pleasure. “A lot of people who have never visited the city see it in a bad light but it’s not an obvious place – you need to find the fun and the hidden gems,” he says. “Once you do, it’s amazing.”

On Sunday mornings, Jakarta’s main thoroughfares close. Cyclists and runners race down major avenues, padel courts are booked out and cafés fill up. After securing coffee at buzzy New York-style café Billy’s Block, we head west to Rubik Office, an exemplar of adaptive reuse in the Indonesian capital. Esteemed architecture firm Shau retained the original 1990s structure, adding an external envelope, a new floor and a biophilic terrace last year. Tomorrow it will be filled with employees of Indonesia Kaya, an organisation that promotes traditional Indonesian arts and culture.

Jakarta-based Domisilium Studio designed the interiors, which juxtapose traditional Indonesian artwork with pops of terrazzo and calming pastels. “I wanted to create a healthy environment for young people doing creative work,” says the studio’s co-founder Santi Alaysius. Jakarta’s younger creatives are taking up Indonesia Kaya’s goal of ensuring cultural handover between generations with increasing gusto. “More and more young people are relearning Javanese folk dances,” says Alaysius. “They’re finding out more about their roots.”

Alaysius returned to the city after spending about 10 years overseas. “Jakarta is huge but it feels like a kampung [village] where everyone creative knows each other,” she says. When we tell her that we’re visiting Chinatown next to meet artist Metta Setiandi, she smiles. “She’s a good friend,” she says. “Our grandparents knew each other.”

Glodok, Jakarta’s historic Chinatown, is one of its most distinctive enclaves. Fittingly – since we’re in a city where caffeine is sacrosanct – our final stop this weekend is MET, a café owned by Metta Setiandi. Chinese Indonesians have faced persecution since the days of the Dutch occupation and the neighbourhood still bears the memory of those ugly times. MET’s mission is to preserve Glodok’s culture by hosting art shows and organising tours of the area. Setiandi spent years travelling but always knew that she wanted to return home. “You have to think of yourself as a seed, choosing between being in the ground or being in a pot,” she says. “Pot plants can go anywhere but trees need to take root. It’s a slow process but one day a tree will grow and provide shade to people. That’s why I came back.” This city has always shaped its people. Now, its people are shaping Jakarta.

Read next: Monocle’s complete city guide to Jakarta