How three family-run French labels found new relevance in a crowded market

By leaning into their heritage and generational know-how, these three Gallic brands have found ways to thrive in the face of stiff international competition.

In France, the idea of patrimoine runs deep: the belief that knowledge and craft can sustain a business as it’s passed down generations. The small or medium-sized businesses associated with this notion are often inextricable from their communities, buoying local livelihoods while pulling in profit. But many heritage businesses have folded after decades of struggling against cheaper overseas competitors. Here, we meet three historic or family-run French brands that turned things around in choppy waters, leaning into their values to find new success.

1.

Heschung

Shoes

“This is the house where my grandfather lived,” says Pierre Heschung, the CEO of the Alsatian shoemaker that bears his family name, as he walks with Monocle past a building in his company’s compound. “My mother still lives here today.” Pierre’s daughter Salomé, who heads the company’s marketing and communications, introduces us to her grandmother, Suzanne, who is taking in the sun in a deckchair between the house and the factory entrance.

Pierre’s grandfather Eugène started Heschung – which now employs 35 workers nationwide, including 20 artisans at its headquarters – in 1934. After years spent working in a shoe factory, Eugène struck out on his own and began making the water-resistant boots that his brand has become famous for, using a special technique known as Norwegian welting. This involves sewing the shoe together using threads soaked in a special pitch; once the sole is stitched to the upper, the pitch hardens and seals the needle holes for extra water protection. The technique remains Heschung’s speciality.

The brand shot to national prominence in the 1970s after manufacturing the French Olympic team’s ski boots. In the 1990s it transformed into a fashion brand selling dress shoes and ginkgo calfskin footwear. In recent years, however, it has faced significant challenges. Sales were hit hard by the gilets jaunes protest movement, which forced shop closures as thousands took to the streets in Paris. The coronavirus pandemic followed soon afterwards and Pierre had to seek outside investors to rescue his now-endangered family firm.

The idea of merging the company with another shoe brand was briefly floated, with an eye towards exporting to China and the US. Some investors pressured Pierre to move production away from Alsace to cut costs but he fought back. The company eventually found a more like-minded partner in Philippe Catteau, the owner of the One Nation shopping mall in Paris’s affluent western suburbs, which pays special attention to showcasing premium French brands.

“I couldn’t let nearly 100 years of crafts- manship disappear,” says Catteau. He acquired 75 per cent of Heschung and invested €2m in machinery. A further €2m went towards estab- lishing new shops in Paris, the latest of which can be found on Rue des Saints Pères, a stone’s throw from Le Bon Marché. “Lowering the quality for short-term profits would have doomed the business,” says Catteau.

With Pierre nearing retirement, Salomé is preparing to succeed him as CEO. This allows the family’s partners to better plan for the future. “We’re thinking 20 or 30 years ahead,” says Catteau. “Naturally, it’s all about quality and being present in the market.” A young workforce and new cutting-edge equipment means that Heschung’s manufacturing operation is ready. “I hope to one day open the doors of our factory to our clients,” says Salomé. “I want them to be able to see for themselves how passionate we are about preserving our know-how.”

Heschung’s recipe for longevity:

1.

Finding like-minded investors who saw the value of keeping manufacturing local.

2.

Not rushing to export and returning the focus to the domestic market, while waiting for the right moment for global expansion.

3.

Investing in old-school craftsmanship while upgrading tools will pay off, combining proven techniques with new technology.

2.

Duralex

Tableware

Duralex’s general manager, François Marciano, is showing off one of the French tableware maker’s classic Picardie glasses. As he turns it in his hand, he fumbles, causing the dark-blue glass to fall and Monocle to scramble to stop it from smashing. When it happens a second and third time – the glass bounces harmlessly against the showroom floor on each occasion – it becomes clear that this is a party trick to demonstrate how durable Duralex is. “We’re the only glass-maker doing tempered glass like this,” says Marciano, explaining that the brand’s glass is several times more solid than the conventional stuff.

With its enduring design and almost unbreakable product, Duralex – a global household name – is a staple of school canteens and domestic kitchens. Established in 1945 near Orléans, its factory HQ is the sort of place that politicians visit during their campaigns to herald a titan of French industry. But the company’s recent history makes for less auspicious reading. It was sold by its then-owner in 2021 to the International Cookware group, the parent company of Pyrex; at times, the leadership seemed more interested in shareholders than safeguarding Duralex’s future. It has experienced six insolvencies since 1996.

When the company was placed into receivership last year, Duralex’s employees decided that enough was enough – it was time to return the brand to its former glory. They put forward a plan for co-operative ownership, known in French as a société coopérative et participative (Scop). Their proposal was accepted in court. Of the brand’s 236 employees, 64 per cent opted into becoming owners, which required a minimum investment of €500.

Drafted in at the time of the co-operative takeover, Vincent Vallin has spent a career at multinationals, including a stint in the UK. The cool-headed director of strategy and development is realistic about the task at hand. Talking to Monocle in a slightly old-fashioned boardroom with brand photos hanging on the walls, he is keen to point out that Duralex’s new ownership isn’t interested in austerity or cuts. There’s a clear plan in place. “The project is based on generating more cashflow by selling more and better, increasing the top line and the margin,” he says. “We also need to streamline the product assortment.”

Because banks won’t lend to Duralex as a result of its financial record, the company has generated funds by selling its HQ to the local municipality and leasing it back. These liquid assets should buy Duralex three years to turn things around, which Vallin believes is time enough. He intends to emphasise the brand’s simplicity and good design, as well as the fact that almost everything that goes into making the glass is French, including sand from Fontainebleau. The team must “extract more value out of the market and make Duralex more premium”, says Vallin. In short, it needs to be seen as more than just a basic tableware staple. It’s also becoming more entrepreneurial. “When I came in, there were only three sales and marketing employees,” says Vallin. “I hired three more for sales in France, five for export and five marketeers.”

On the factory floor, orange molten glass zips around the production line as automated arms hiss and thud. Even to non-expert eyes, it’s clear that the facilities need an update. But Duralex has one thing in abundance: heart. “I’ve given my life to this job,” says Stéphane Lefevre, a team leader who, like everyone else on the factory floor, is dressed in blue work overalls. “The co-operative wasn’t a choice. It was an obligation.” Lefevre has spent more than 24 years at the company and isn’t ready to give up on it yet.

There’s clearly a feeling that Duralex is finally in the right hands and it is ambitious about the future. Back in the showroom, Marciano is hovering around the glassware and food containers on display and enthusing about new items, from the recently released black espresso cups to premium pint glasses that are set for release next year. A new website launched in June, while in May, Duralex opened Café Duralex, its first bricks-and-mortar outlet in the French capital, collaborating with grocery shop l’Épicerie de Loïc B. (Another opened at the end of last year in Orléans.) There are also plans for a factory shop and a museum in La Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin in the next few years.

Duralex might be hitting the gas after its years of torpor but a slow-and-steady approach is still the order of the day. Marciano, the glass-dropping joker, turns serious for a moment. “With a brand like ours,” he says, “you can’t make mistakes.”

How Duralex is turning it around:

1.

Since going into employee ownership, the brand has been investing in both people and product.

2.

Leveraging its “Made in France” legacy.

3.

Getting closer to the buyer by recognising regional nuance and the need for new physical shops.

3.

Fournival Altesse

Brushes

The Oise department is best known for its chateaux and peaceful villages but this leafy enclave an hour north of Paris is also the last stronghold of a vanishing craft. Oise was once France’s brush-making capital, where artisans specialised in crafting elegant tools fit for the vanity tables of royalty. “At the peak of the industry, there were almost 100 companies making hairbrushes here,” says Julia Tissot-Gaillard, the CEO of Fournival Altesse, as she 1 welcomes Monocle to her company’s historic factory. “We are the only ones left.”

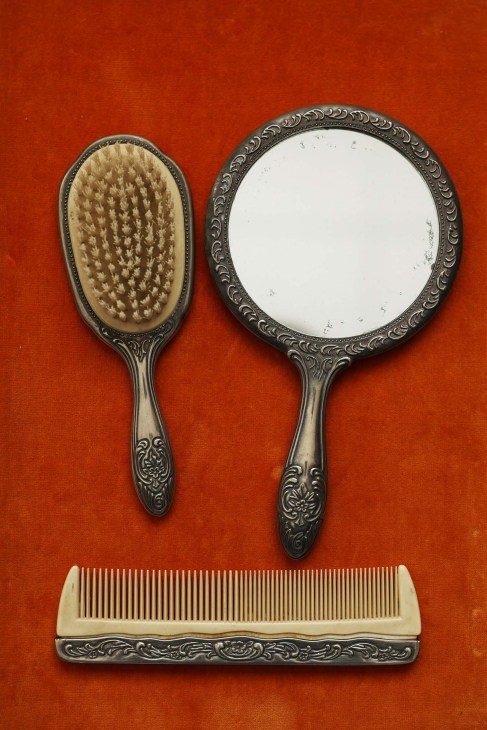

In a light-filled meeting room, rows of glass cabinets display Fournival Altesse’s detangling brushes, beard combs and more. Tissot-Gaillard picks up a wooden hairbrush made from boar hair, running her thumb across the bristles so they make a dry, satisfying sound. “It has to be stiff,” she says. “If you get one of these under your nail, it hurts – and that’s how it should be. If it’s too soft, it’s useless.”

Founded in 1875 by Léon Étienne Fournival, Fournival Altesse originally fashioned toothbrushes using ox bone, horse 2 bone or ivory. The business later expanded into hairbrushes, which became popular in Parisian pharmacies, perfumeries and salons.

It remained in the family for five generations until the early 2000s, when cheap imports began replacing the more labour-intensive French products. By the time Tissot-Gaillard stepped in to take over in 2016 (when she was just 28 years old), the company had been losing money for a decade. Her stepfather, Jacques Gaillard, a former owner of La Brosse

et Dupont group and a third-generation brush-maker, bought it in 2005 when it was about to go under. “He said to me, ‘Close the 3 company if you think that there’s no hope or bring it back to life,’” says Tissot-Gaillard. “It was a challenge but that’s exactly what I did.”

Tissot-Gaillard immersed herself in the manufacturing process, learning from the craftspeople. She soon realised that she had to raise prices. “We were making amazing, high-quality products, with so much skill and passion, but we were undervaluing them,” she says. “I told our clients that we were increasing prices by 100 to 150 per cent. Either that, or we closed. Thankfully, most of them stayed.”

Today, Fournival Altesse makes hairbrushes for brands such as Dior, Kérastase and La Bonne Brosse. “Almost all French-made hairbrushes of this kind in the world, no matter the brand, come from our company,” says Tissot-Gaillard. But the company also has its own flagship brand, Altesse Studio, to showcase its ancestral know-how. “For purists like us, a brush has to be made from wood and boar bristle is the only fibre that brings genuine benefits to your hair,” says Tissot-Gaillard. “A good brush will massage your scalp, stimulate blood flow and help nutrients reach the tips of your hair. It’s the most important haircare tool.”

In 2017, Altesse Studio earned the Living Heritage Company label, a mark of distinction from the French government for excellence in traditional skills. The factory, still on its original site, employs 50 people and most of the production is still done by hand, from shaping the handles to tipping the bristles. The only mechanised step – inserting the bristles into the brush – is done by 1950s machines, though the owners recently invested in modern models. “They’re the first machines that the company has bought in 30 years,” says Tissot-Gaillard with pride.

As consumers seek personalised, lasting tools that suit their hair types, consumer appetite for artisanal brushes is rising. Luxury haircare, which boomed during the coronavirus pandemic, continues to grow as a sector and is expected to be worth €28.58bn globally by 2032, according to Fortune Business Insights.

To satisfy this growing demand, Altesse Studio has a ‘Prestige’ collection, consisting of brushes made entirely by hand with olive wood and boar bristles of the highest quality, using a 19th-century hand-tufting technique. Costing €350, each brush takes six to seven hours to produce and is numbered, repairable and crafted to last. “We have adjusted the tufting technique and the bristles to suit any hair type, so a grandmother could pass it down to her granddaughter,” she says.

With those difficult years now behind it and a 150th anniversary on the horizon, Fournival Altesse’s future looks bright. The business is not just preserving heritage but proving that it still has worth. “Human values are important to us. If people are happy, they’ll do their best,” says Tissot-Gaillard, as laughter peals from the canteen nextdoor. “At lunch, we play cards. That’s part of it too.”

How Fournival Altesse brushed away its challenges:

1.

Tissot-Gaillard approached her role as ceo with humility and spent time learning from artisans

2.

She raised prices to better reflect the brand’s craftsmanship; clients recognised the value and stayed.

3.

She then launched a luxury range to emphasise Altesse Studio’s heritage and know-how.