Culture: Neighbourhood revival / L’Hospitalet de Llobregat

Industrial action

We head to the outskirts of the Catalan capital, where an arts festival and influx of creatives are working to bring about lasting cultural change.

Can Trinxet, a textile factory built in 1890, has laid empty in L’Hospitalet de Llobregat – a city to the southwest of Barcelona – for decades. Once the largest manufacturing complex in the area, it is now a vestige of Catalonia’s industrial heyday, when people from all over Spain came to the region in search of work. Today the former factory has been given a new lease of life by Barcelona-based architecture studio Self Office. The building’s roof has been restored, while the walls have been painted white to host an installation during the Manifesta Nomadic Biennial, an art and culture festival running throughout the autumn.

In a bid to decentralise Barcelona’s art scene, the event’s 15th edition is taking place across the Catalan capital and 12 neighbouring cities, including L’Hospitalet. “The centre of Barcelona hosts most of the area’s cultural institutions but people live outside it because housing prices are too high,” says Hedwig Fijen, founder of Manifesta.

L’Hospitalet, a commuter town and one of the most densely populated places in the EU, is putting culture front and centre of its urban strategy. Over the past decade, the city council has been building a Cultural District in a bid to lure creatives to the area and revive its economy. According to officials, some 500 cultural entities – art galleries, architecture practices and dance studios – have moved here in recent years, attracted by spacious industrial buildings and low rents. Spanish singer Rosalía recently announced that she would be transforming an old office building into one of the best-equipped recording studios in Europe.

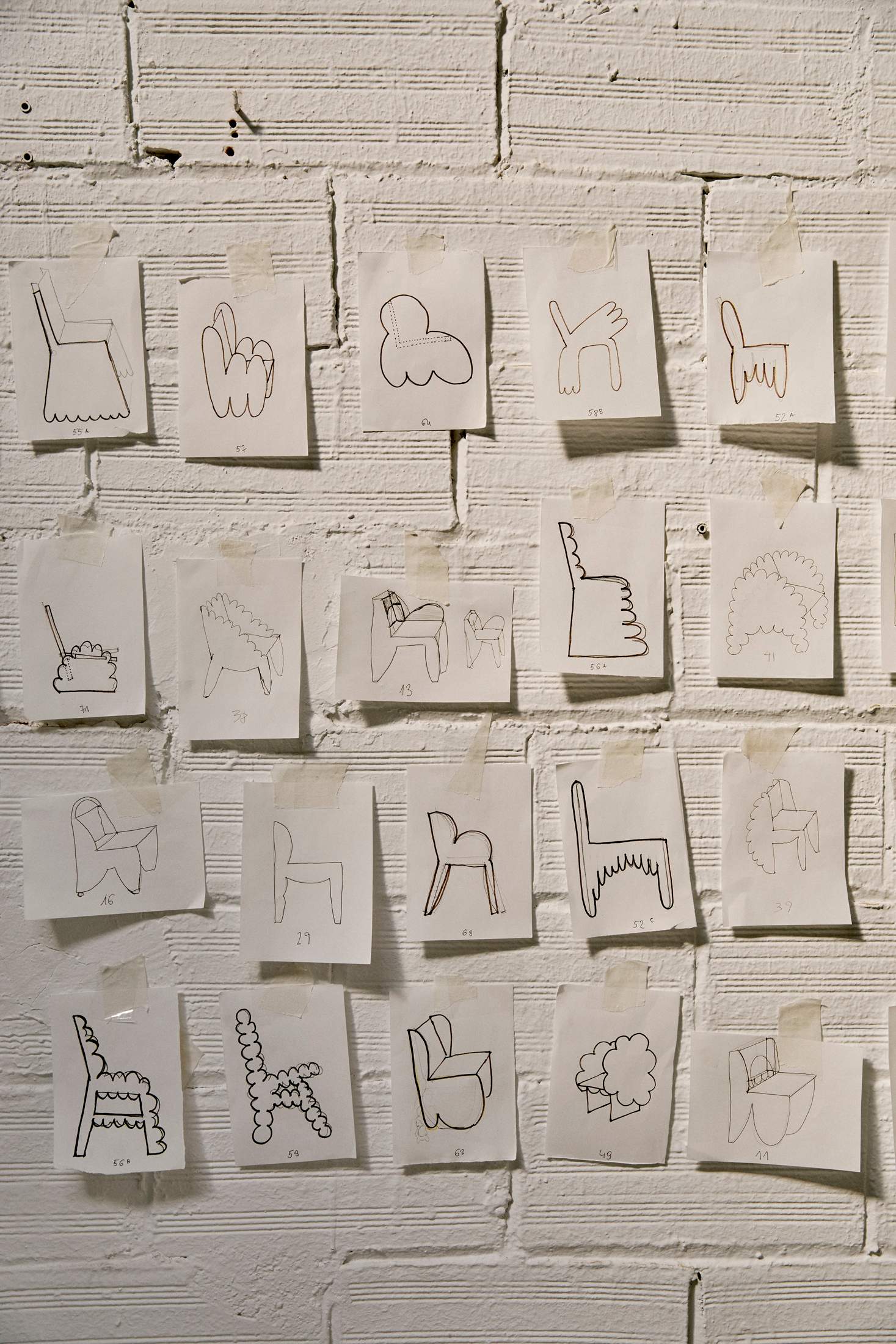

L’Hospitalet’s fragmented urban fabric consists of modern skyscrapers and warehouses, a medieval town centre and neighbourhoods with apartments built in the 1960s and 1970s. “I wanted a generous space to work in, which is hard to find in Barcelona,” says designer Jorge Suárez-Kilzi as he welcomes monocle into his studio on the top floor of Edifici Freixas. The 1960s-era six-storey building was built for heavy industry and craftspeople. While it’s still home to a few carpenters and glassworkers, it now houses a growing number of artists. “Moving here came out of the necessity of finding an alternative to Poblenou,” says Suárez-Kilzi, referencing the trendy former industrial neighbourhood in Barcelona. That area is now “more established,” he says, as start-ups, technology companies and luxury hotels have moved in.

Uri Rivero and María Vázquez also considered setting up shop in Poblenou before stumbling across a 1970s factory near Edifici Freixas in L’Hospitalet. They have transformed the space into Industrial Akroll, a 2,000 sq m space dedicated to photography and film. The former manufacturing hub, which originally produced metal accessories, had been empty for 20 years. “The Cultural District project was a bit of a siren call for us,” says Rivero. “We knew that some art galleries had moved to the area. Plus, being here meant that we would have suppliers nearby.”

In the early 2010s, the city council created a team dedicated to helping new arrivals with paperwork and permits, as well as access to funding for projects. “We want to make people feel comfortable so that they stay,” says Mireia Mascarell, the council official responsible for L’Hospitalet Cultural District. The regional revival has attracted large, private projects too. Last December, La Caixa Foundation announced that it would convert a warehouse in L’Hospitalet into the Art Studio Caixa Forum, a new cultural facility that will host 1,039 pieces from its contemporary art collection. The Godó i Trias factory will also be turned into a centre for visual arts by Stoneweg Places and Experiences, with the help of Pritzker Prize-winning architecture studio rcr Arquitectes.

“It’s good that visibility is being given to not just Barcelona but the entire region,” says Vázquez of Manifesta. Of the eight million tourists who visit Barcelona every year, only a few venture beyond its iconic Catalan modernism buildings and urban beaches to explore its outer limits. The biennial’s inclusive approach is therefore one that officials across Europe are watching closely.

“Barcelona is attractive to tourists in a way that exceeds its capacity to welcome and respond,” says Xavier Marcé, city councillor for culture and creative industries, who was born in L’Hospitalet. “Because we have decided to crack down on short-term tourist rentals, we have to try to attract visitors in a different way. I believe that highlighting spaces across the metropolitan area and making the offering more cultural will appeal to the type of person that wants to experience the real Barcelona.”

This cultural expansion, however, has led many to question the role that it is playing in the process of gentrification. According to a study by Spanish property portal Fotocasa, rental prices in L’Hospitalet – a largely working- class area – went up by 17.5 per cent in 2023. Mascarell says that “for now, there is no gentrification”. But that could change, with visual artists already outnumbered by advertising agencies, architecture practices and recording studios. Some fear that L’Hospitalet might end up drifting from its industrial roots in the same way as Poblenou.

Despite these challenges, many are hopeful that the arrival of Manifesta and figures such as Rosalía will create a richer cultural landscape that supports newcomers and long-term residents. “It’s positive that people are moving here with new ideas,” says flamenco artist Jose Manuel Álvarez, who grew up in L’Hospitalet and returned to open dance studio La Capitana. His students, who come from towns in the metropolitan area, take classes in the same rooms where Rosalía choreographed dance routines for her 2018 album El Mal Querer. “If all these buildings are empty, why not bring them back to life?” —