Edo Tokyo Kirari Monocle

Bringing japan to your home

Look behind Tokyo’s fast-paced façade and you will discover more than 3,000 businesses that are more than a century old. All over the city, artisans are making everything from textiles to knives using traditional skills that have been passed down from generation to generation. The Edo Tokyo Kirari project celebrates these heritage names, introducing their stories and products to the world. This directory is an opportunity to find out more about a few of these remarkable companies and discover how they are preserving old techniques – and keeping them alive in the modern world.

The Edo Tokyo Kirari project allows shoppers from around the world to buy fashion, food and crafts from some of the oldest merchants and makers in the Japanese capital.

store.kirari.metro.tokyo.lg.jp

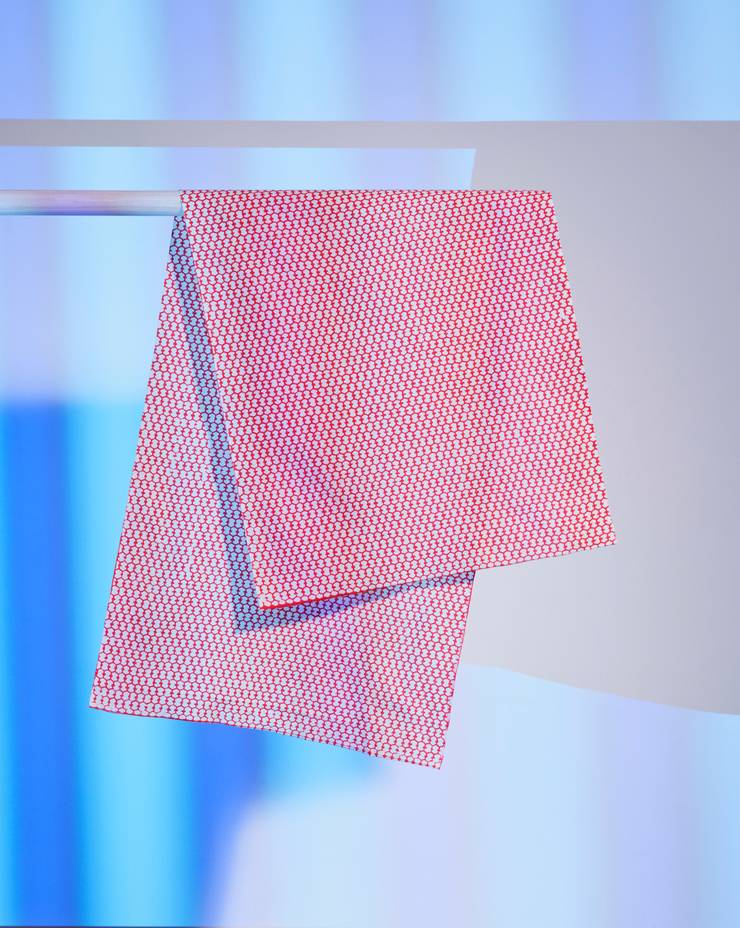

HIROSE DYEWORKS:

Hirose Dyeworks specialises in the craft of Edo komon stencil dyeing. The traditional fabric is kimono silk but the current head, Yuichi Hirose, has also applied the technique to beautiful cashmere and silk shawls, using the same-komon (shark skin) motif.

UBUKEYA:

This family-run craftsman-merchant has specialised in knives, scissors and bladed goods for generations. This Damascus Gyuto chef’s knife is made with a 19.5cm Super Gold 2 blade that does not rust easily.

1.

Hanashyo

Glassware

First made in the Nihonbashi district nearly two hundred years ago, Edo cut glass (or Edo-kiriko) is one of Tokyo’s most celebrated crafts. Hanashyo has been making colourful treasures, including wine glasses, plates, bowls and saké cups, since 1946. Second-generation craftsman Ryuichi Kumakura and his son Takayuki lead a team of seven in their shop and atelier in Kameido, Tokyo.

Hanashyo is renowned for creating its own patterns and motifs, as well as for the exceptional precision of its work. The entire process is done by hand and can’t be rushed: it takes time to complete a single piece.

2.

Toshimaya

Brewery

Founded in 1596 as a tavern and sake shop in central Edo, Toshimaya started brewing its own sake 12 generations down the line and production moved to Higashimurayama in western Tokyo in the 20th century. Today the brewery makes sake, shirozake (sweet white sake) and mirin – a sweet sake that is an essential part of Japanese cooking. Toshimaya’s award-winning Kinkon sake is used at Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu and Kanda Myojin shrines as a sacred offering. The brewery has a sake bar and shop in Kanda and thrives on a simple principle: “We preserve what needs to be preserved while changing what needs to be changed”.

3.

Takahashi Kobo

Printmaker

In the era before photography, the landmarks and people of Edo (as Tokyo was known prior to 1868) were recorded in the ukiyo-e prints of artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige. Tokyo printmaking atelier Takahashi Kobo has used the same materials and techniques for 160 years and remains committed to making woodblock prints the traditional way. Artisans here use wild cherry wood, horse-hair paintbrushes and the highest-grade washi paper called echizen-kizu-hoshoshi. Takahashi Kobo is safeguarding a craft that stretches back four centuries, reproducing classic prints with all the vibrancy of the originals.

4.

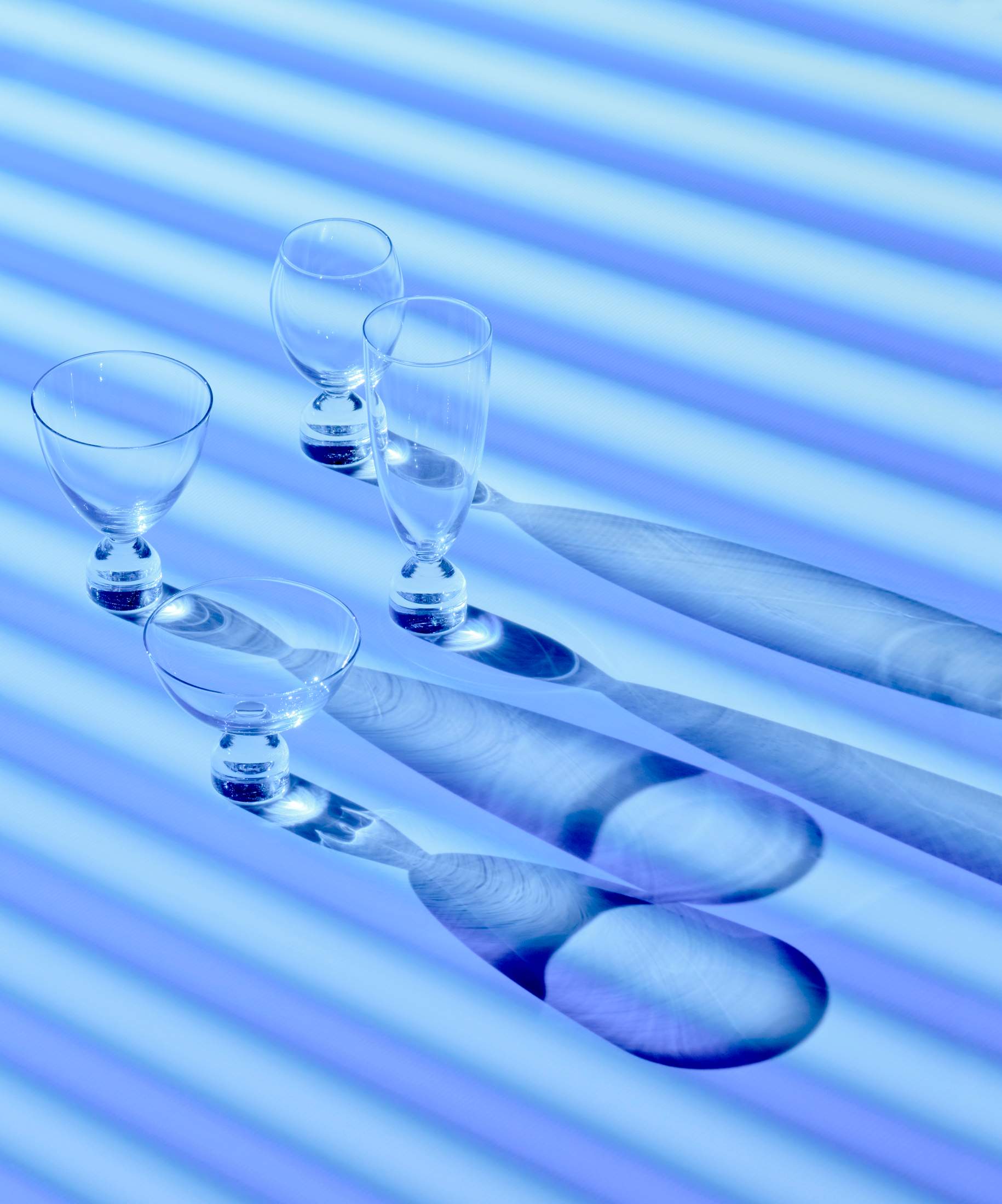

Kimoto Glass Tokyo

Glassware

Established as a wholesaler in 1931, Kimoto Glass Tokyo knows everything there is to know about the glass business in Japan. The industry has been challenged by cheap imports but Kimoto Glass Tokyo is working hard with makers and designers to keep the craft of glass alive and thriving. The company commissioned the skilled craftsmen at trusted partner Tajima Glass to produce Edo-kiriko pieces in black – a difficult colour to achieve. It also collaborated with a Tokyo brewery to create bespoke drinking vessels for different flavours and types of sake.

Meet the maker

Nakamura

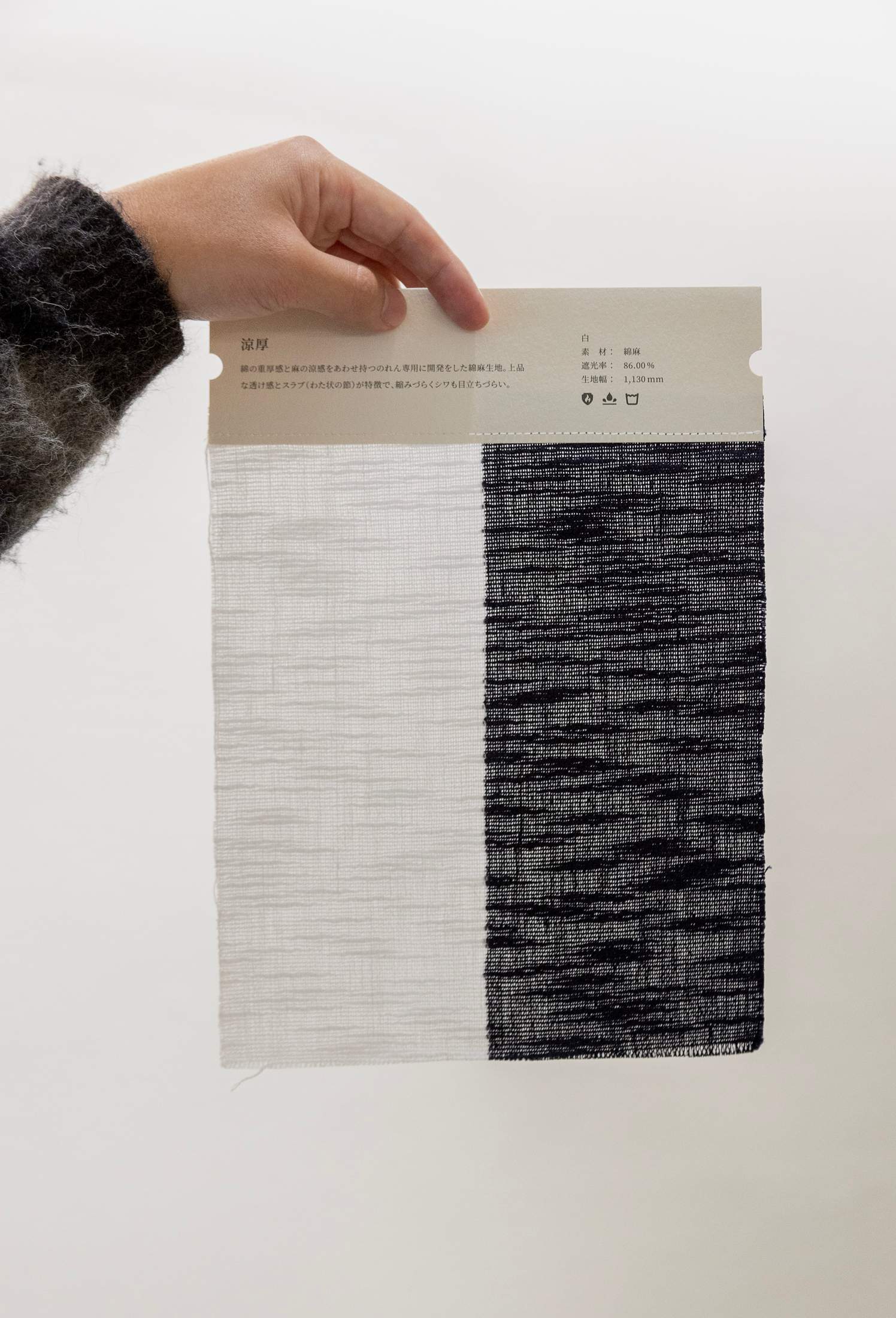

Noren

In Japan, you will see noren (fabric curtains) hanging over the entrances of restaurants, ryokan and shops, softly defining the border between spaces without the need for a door. Noren also act as a welcome sign, showing the name or crest of the business within – like a traditional version of the neon light.

Shin Nakamura

Fabric samples with intricate cloud patterns.

An example of Nakamura's dye techniques

One of his company’s colourful noren designs

Shin Nakamura is bringing a fresh perspective to traditional Japanese crafts. The 36-year-old Edokko (a person born and raised in downtown Tokyo) was born into a family kimono business that was established in 1923. While the original company closed in 2006, Nakamura – then working in the energy industry – decided to revive the name by starting his own business in 2014 that specialised in noren. “When I left my previous job, I wanted to work on something rooted in Japanese culture,” says Nakamura. By chance, he happened to meet an artisan who specialised in noren dyeing. “I saw a gap: there was a demand and lots of great makers but not many people who were connecting the two sides in the middle.”

Today, Nakamura closely works with a network of companies, designers and craftsmen across the country that are using a mix of new and old techniques such as aizome Japanese indigo dyeing, embroidery and inkjet printing. Nakamura has created bespoke noren for the likes of venerable Japanese confectioners Toraya, Coredo Muromachi shopping centre and Hakuunso ryokan in Yugawara. “There is great potential for noren to become popular overseas,” he says.

A noren doesn’t just belong in a traditional ryokan. Nakamura has made them for the Japan Pavilion at the Milan Expo and the Ace Hotel Kyoto – the latter featuring artwork by Samiro Yunoki. “Noren are uniquely Japanese,” says Nakamura. “I want to promote the skills of our craftsmen through them.”

5.

Yotsuya Sanei

Footwear

Established in 1935, Yotsuya Sanei makes traditional Japanese sandals known as zori and geta. The Tokyo shop, which is frequented by geisha and tea ceremony practitioners, is also home to an atelier where the president Sotaro Ito works with his son Makoto and daughter-in-law Junko. The family teams up with craftspeople across Japan and uses traditional skills and materials for its beautiful footwear: bamboo for everyday zori and delicate leathers in a dazzling array of colours to wear with kimono.

6.

White Rose

Rainwear

Originally an 18th-century tobacco merchant, White Rose changed to meet the needs of the time and became a rainwear maker. Today, the 10th-generation president Tsukasa Sudo heads this small family affair, producing 1,000 premium plastic umbrellas every month. “My father invented plastic umbrellas in the 1950s,” says Sudo. “We’re the only company still making them in Japan.” \

Longevity is guaranteed. Sudo offers repairs and his company’s products last for more than a decade. Everyone loves a White Rose umbrella, including the Japanese royal family.

7.

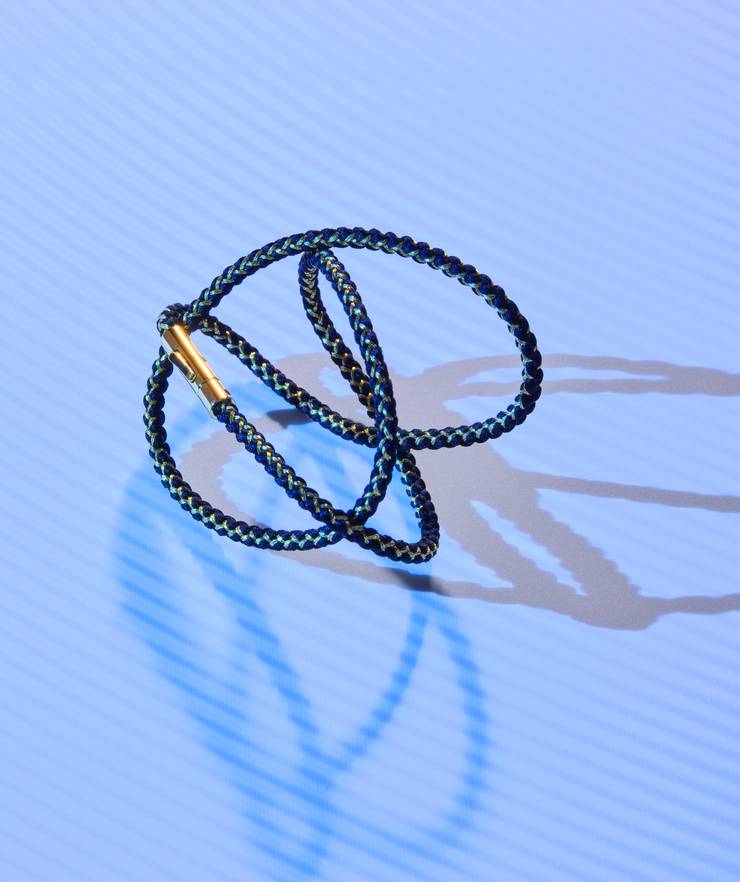

Ryukobo

Accessories

Ryukobo opened for business in 1963 but its craft – kumihimo, a traditional Japanese braiding technique – stretches back 1,400 years. Kumihimo braids are made with fine silks and used as decorations at shrines and for securing sword sheaths. From spinning and dyeing to designing and braiding, Ryukobo is the only contemporary workshop in Tokyo that still handles the entire kumihimo process. Owner Takashi Fukuda is a master who works by hand on a kumidai braiding table. His complex and beautiful obijime (sash cord) are beloved of kabuki actors, tea ceremony practitioners and the Imperial family.

Meet the maker

Ubukeya

Bladesmith

In Edo, it was common to find craftsmen-merchants who not only sold knives, shoes and umbrellas but also maintained and repaired them. Ubukeya is continuing that tradition, forging long relationships with makers and customers alike. In Ubukeya’s small workshop, raw blades are turned into lifelong tools.

Ubukeya’s father-and-son team Yutaka (right) and Taiki Yazaki

A selection of the shop’s large-handled scissors.

Ubukeya blades are handcrafted; a selection

The firm’s traditional Nihonbashi workshop

Time seems to slow down when you walk through the door of Ubukeya, a business which has been selling all manner of blades since 1783. The hustle and bustle of Nihonbashi is instantly muted as you enter the warm wooden interior to be greeted by Yutaka Yazaki, who kneels behind the counter on tatami matting in the old-fashioned way.

The vintage cabinets are lined with knives, tweezers, scissors and razors. Chefs come here for the magnolia-handled knives, sumo hairdressers buy traditional scissors to trim wrestlers’ topknots, while gardeners visit in search of the large-handled scissors that snip with precision. Ubukeya is both a merchant and a workshop: some raw, handcrafted blades are delivered here to be ground, sharpened and fitted with handles.

This is a family business: Yutaka grew up above the shop and he works here with his wife Misako and son Taiki, a literature graduate who will eventually take charge. Blade maintenance is a crucial part of the business – and keeps customers coming back. Ubukeya has adapted to the times, offering easier to maintain Western-style kitchen knives alongside the traditional Japanese offerings. The business is part of Tokyo’s history and its relationships with partner workshops go back generations. With more than 45 years in the knife industry, Yutaka Yazaki is a worthy guardian of this special enterprise.

8.

Yonoya Kushiho

Accessories

Tucked away on a side street, close to the great temple of Sensoji, is Yonoya Kushiho. This maker of traditional combs first opened in 1717 and exclusively uses quality Satsuma boxwood from Kagoshima in western Japan. The wood is strong yet flexible, so it gently massages the scalp. Each tooth on a Yonoya comb is filed by hand and the finishing touch is a soak in fragrant camellia oil. Sumo wrestlers and kabuki actors have long used these beautiful combs and they are perfect for everyday use too. As time passes, the boxwood’s golden colour turns to a rich amber and, with care, these combs can last a lifetime.

9.

Marukyu Shouten

Fabrics

Marukyu Shouten began life in 1899 in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district as a kimono wholesaler specialising in chusen – a traditional stencil-dyeing technique. More than 120 years later, skilled craftsmen use those same techniques apply intricate stencil patterns to yukata (summer robes) and tenugui (towels). Since these products are dyed by hand, every piece of cloth comes out slightly differently, giving the products a warm character that mass-produced goods can’t deliver. Marukyu Shouten has also used its extensive archive of classic stencil dye patterns to launch a shirt brand, TEWSEN, that is proudly made in Tokyo.

10.

Tsuchiya Kaban

Leather goods

Tsuchiya Kaban is a household name in Japan thanks to its randoseru – the robust leather rucksacks used by primary school students up and down the country. Kunio Tsuchiya started making randoseru (the word comes from ransel, Dutch for “backpack”) in 1965 with two craftsmen and one sewing machine. Making each bag required 150 parts and 300 processes; the brand’s reputation for quality soon spread. In 2000, Tsuchiya Kaban responded to requests for adult bags by launching a collection of smart leather goods. Today, 200 craftsmen of all ages make totes, wallets, handbags and, of course, the famous randoseru.

*The companies shown here represent a sample of those that feature in the Edo Kirari Project. Head to the website below to find out more about historic companies such as confectioner Eitaro Sohonpo, famed for its pickled plum sweets, or Matsuzaki Doll, makers of exquisite festival dolls, and Chikusen, who has been making fashionable yukata cotton robes since 1842.

edotokyokirari.jp

Directory

A selection of the merchants and makers featured in the Edo Tokyo Kirari project.

Chikusen

Kimono fabrics.

2-3 Nihonbashi Kobuna-cho, Chuo-ku

chikusen.co.jp

Edo-kumiko Tatematsu

Intricate kumiko wooden items.

www.paw.hi-ho.ne.jp/kumiko-

Hanashyo

Edo-kiriko cut glass.

3-6-5 Nihonbashi Honcho, Chuo-ku

edokiriko.co.jp

Hirose Dyeworks

Stencil-dyed silks.

komonhirose.co.jp

Kimoto Glass

Made-in-Tokyo glassware.

2-18-17 Kojima, Taito-ku

kimotoglass.tokyo

Kyogen

Hand-drawn family crests.

kyogen-kamon.com

Marukyu Shouten

Chusen stencil-dyed textiles.

1-4-1 Nihonbashi Horidome-cho, Chuo-ku

shinedozome.com

Matsuzaki Doll

Dolls for traditional festivals.

2-4-6 Kurihara, Adachi-ku

koikko.com

Miyamoto Unosuke

Portable shrines and drums.

2-1-1 Nishi Asakusa, Taito-ku

miyamoto-unosuke.co.jp

Nakamura

Noren curtain specialist.

nakamura-inc.jp

Porter Classic

Fashion label by Katsuyuki and Leo Yoshida.

Ginza Five 2F, 5-1 Ginza, Chuo-ku

porterclassic.com

Ryukobo

Fine silk braids.

ryukobo.jp

Takahashi Kobo

Ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

2-4-19 Suido, Bunkyo-ku

takahashi-kobo.com

Toshimaya

Tokyo’s oldest sake shop.

toshimaya.co.jp

Tsuchiya Kaban

Classic leather school bags.

7-15-5 Nishiarai, Adachi-ku

tsuchiya-kaban.com

Ubukeya

Family-run knife shop.

3-9-2 Nihonbashi Ningyocho, Chuo-ku

ubukeya.com

White Rose

Premium quality plastic umbrellas.

2-4-8 Kotobuki, Taito-ku

whiterose.jp

Yamamoto Noriten

Nori seaweed since 1849.

1-6-3 Nihonbashi Muromachi, Chuo-ku

yamamotonori-shop.jp

Yonoya Kushiho

Boxwood combs and hair accessories.

1-37-10 Asakusa, Taito-ku

en.yonoya.com

Yotsuya Sanei

Handmade Japanese sandals.

3-13 Yotsuya, Shinjuku-ku

yotsuya-sanei.co.jp