Design: Architecture / Norway

Cabin fever

A country lodge – or ‘hytte’ – in which to escape the city and reconnect with nature has long been on the wish list of every Norwegian urbanite. As demand for these retreats grows, we meet the architects behind three modern exemplars across the country.

For centuries, Norwegians from all walks of life have been making their way to seasonal rural residences. These hytter (holiday homes) and årestuer (traditional huts) offer a base for favourite Norwegian pastimes of hunting, fishing, hiking and cross-country skiing.

With some 450,000 of these structures spread across the country (and one in three families in Norway owning one), it’s no surprise that some of the country’s finest architects are turning a hand to their design. Across the next few pages, we visit three outstanding examples. —

1.

THE BLENDED BUILD

Norefjell

Office Kim Lenschow

Cabin culture and the desire for a holiday in nature – whether a lengthy summer on the lake or cosy winter weekend – is not unique to Norway among northern European nations. But the development of the hytte is. This humble holiday cottage has its roots in the vacation habits of the country’s city dwellers and their desire to escape from urban areas, going off-grid in simple huts, so as to allow themselves to be immersed in Norway’s rugged landscapes. These forces are still present in the hytte of today.

“These are places where you step out of your normal routines and live life differently, almost allowing yourself to be bored,” says Kim Lenschow of these countryside retreats. The Copenhagen-based Norwegian architect has recently finished one of these small, traditional timber holiday cabins in a rocky area northwest of Oslo.

Located 800 metres above sea level in Norefjell, this cabin was commissioned by a friend of the architect, who discovered the plot while searching for the perfect spot to build his own country escape. “This project was about bringing traditional elements of a hytte to life through modern construction,” says Lenschow, whose approach to architecture is defined by a desire to create harmony between the built world and the natural environment.

“The area surrounding Norefjell is beautiful,” says Lenschow. “You have this rocky terrain contrasted by spruce trees.” The architect adds that one of his guiding principles for the project was to ensure that the cabin complemented its surroundings. “We wanted to understand the relationship between architecture and nature.”

To explore this relationship, Lenschow identified the need for the building’s colour and materials to work in harmony with the surroundings. “Architecture and nature are opposites in a way, because you’re adding something to a landscape with a specific logic in mind,” he says. “So the most effective approach was to emphasise simplicity and use colours that complemented the muted tones of the woodlands.” The resulting palette of primarily earthy tones allows the home to bleed visually into the background, and is particularly evident in the exterior surfaces, which feature two distinct elements.

On one side, the façade is finished with a textured render applied over the underlying brick structure. This grooved, light-grey surface gives the exterior a unique character – and creates striking shadows on sunny days – without clashing with the rocky terrain on which it sits. “We wanted to add subtle details to make it clear that this wasn’t just part of the rock,” says Lenschow. “But it also could not be too bold.”

On the opposite side, facing the sloping landscape and expansive woodland, is a façade made from spruce sourced from the local region. The timber is treated using iron vitriol, which speeds up the initial decay of the wood to create a protective surface that can endure harsh winters. Connection with the landscape is enhanced on this side of the building thanks to three-metre-high windows that frame sweeping views of the surrounding terrain. To further intensify this relationship with the natural world, Lenschow positioned the building in such a way that the boulders and natural elements block sightlines to the road. “The surrounding rocks almost become part of the furniture,” he says.

The colour, material and windows have helped this hytte to blend into the landscape but Lenschow didn’t want to completely disguise the building, so he opted for a straightforward geometric design. “It wasn’t about coming up with clever shapes to camouflage the house,” says the architect. “I like it when a building is proudly a work of architecture but still resonates with the setting.”

It’s a theme that continues inside, where the hytte’s floors belie the challenging terrain on which it sits. Rather than smoothing out the plot, Lenschow designed the structure so that the site’s varied grade define its rooms, utilising single steps to act as dividers between them. “We worked with the natural levels of the ground to section off different spaces,” he says. A bedroom sits on one level and a living room on another, with a separate kitchen level creating the sensation of walking on uneven terrain as you move through the house. “You almost feel like you’re outside.”

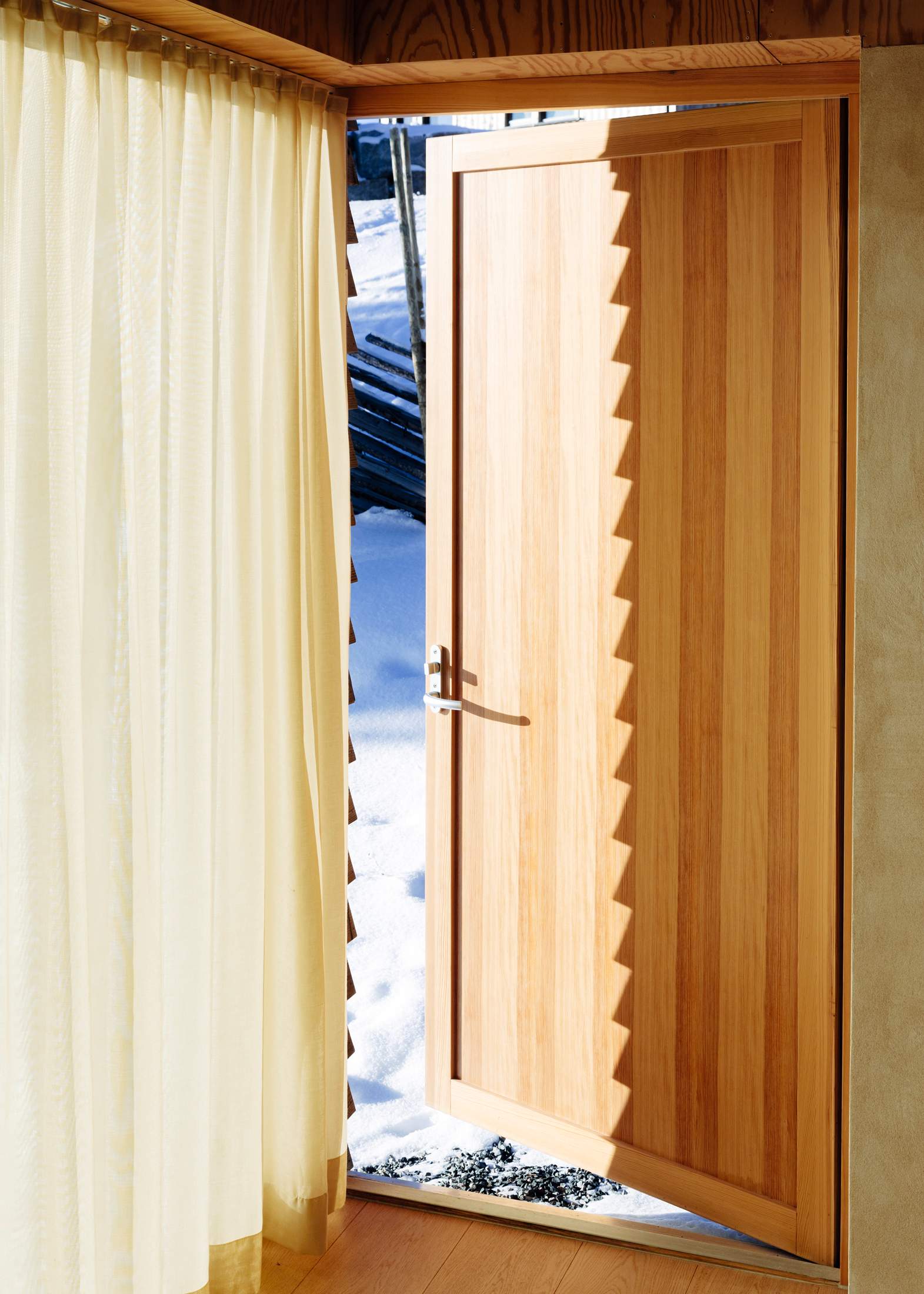

Crisp weather, light and shadows

The interiors are kept simple. Many of the rooms are clad in a light wood, which is bathed in natural light even during the darkest months of the year. There’s a sense of spaciousness too, with minimal furnishings – a mix of Nordic design classics and wooden pieces – complementing the building’s palette. “The furniture, like the building, is very simple,” says Lenschow. “It gives the space a cosy feel.”

Key items include a rattan and teak cabinet by Danish homeware brand Nordal, and a modular L-shaped sofa in cream that defines the lounge area. Next to it, a step leads to the dining space, which features a long wooden table surrounded by Bambi 57/4 dining chairs – a 1955 design by Rastad & Relling now produced by Norwegian furniture brand Fjordfiesta. Behind this, floor-to-ceiling windows with light-hued semi-transparent curtains diffuse light throughout the space.

For Lenschow, designing this hytte meant creating a new structure equipped with modern amenities, while preserving the traditional essence of an off-grid retreat by way of simple construction and a deep connection with nature. “What the modern country escape looks like is an ongoing conversation in Norway,” says the architect. “It’s not about going back in time; it’s about each individual’s interpretation of what it means to be immersed in nature. For some, this means having a cabin in a remote spot, only accessible by skis. For others, it’s simply about being surrounded by stillness. What a hytte means to you is very personal.”

kimlenschow.com

2.

THE NEW VISION

Årestua

Gartnerfuglen Arkitekter

“We believe that every building should have its own soul,” says architect Ole Larsen of Oslo’s Gartnerfuglen Arkitekter, a firm he co-founded with Astrid Wang and Olav Lunde Arneberg in 2014. “Our aim is to uncover the unique potential of every project, rather than applying a specific signature style to everything we do,” adds Wang.

Case in point is Årestua, a newly finished holiday home for a family, inspired by the traditional design of årestue: traditional wooden homes built around an open fireplace. Located in Telemark, a region southwest of Oslo, it has been built using traditional methods, with specialist carpenters carefully stacking timber logs to form walls. “This construction method was a beautiful way to connect architecture with its place,” says Wang.

It’s an approach that also allowed the architects to explore how traditional architectural vernaculars, such as the årestue, can be reimagined for modern living. “Traditionally, this type of cabin is quite dark and enclosed, a place to retreat to after a long day outdoors,” says Larsen. “We wanted to preserve some traditional elements while also being innovative.”

In response to this ambition, the house’s layout is organised into five distinct volumes that house the bedrooms and bathroom, all centred around a main living area fitted with a fireplace. Expansive windows frame sweeping views of the snowy woodlands, creating a seamless connection between indoors and the surrounding landscape. The furniture is carefully positioned to encourage connection around the central living area. “Using the space is about being together,” says Wang. “We’ve added large windows to bring in plenty of natural light. That transforms the space.”

There are also unexpected architectural interventions that respond to the habits of its inhabitants: a small outdoor staircase by one of the doors provides a cosy spot for the family to enjoy classic Norwegian clover-shaped waffles while taking in the view. Additionally, one of the connecting rooms, elevated above the others, includes a window specifically positioned for observing the eagles that soar around the cabin.

“Building the right cabin is all about the small details,” says Larsen. “As an architect, it’s essential to keep an open mind when designing a cabin and to let the location and the inhabitants shape the space.”

3.

THE SIMPLE SPACE

Mylla

Fjord Arkitekter

Despite its proximity to the city, the landscape surrounding Oslo remains largely unspoilt, characterised by mountains, vast stretches of forest, occasional lakes and cross-country ski trails. And though the area is dotted with cabins to which those in the Norwegian capital retreat during the holidays, for the architects practising here, creating buildings that have a “light touch” is essential to preserving these environmental qualities.

It’s something that Oslo-based studio Fjord Arkitekter has done with aplomb on a cabin project called Mylla. The design of this contemporary hytte is rooted in simplicity and sustainability. “The construction is made simple and rational,” says Fjord Arkitekter partner Finn Magnus Rasmussen. “And the materials are durable and natural.”

For proof, he points to the exterior, which is clad in pine treated in the Møre Royal style, a time-honoured Norwegian method that involves vacuum-cooking the wood in oil, creating a durable and weather-resistant surface that ages gracefully. This approach reduces the need for extensive ongoing maintenance or harmful chemical weatherproofing treatments. The hytte also uses a geothermal heating system. But, recognising that green credentials mean little without quality space, the architects have prioritised a calming interior. Oiled spruce walls and ceilings create a warm and inviting atmosphere, while a central sculptural staircase divides the space into zones.

“The cabin is elongated and narrow for the best adaptation to the plot,” says Rasmussen. “It provides distance between the quiet and active parts of the cabin. It might have a sober exterior but when you get inside, it is rich in spatial qualities.”

fjordarkitekter.no