Big interviews / Global

Leading the way

What drives the movers and shakers in today’s business landscape? We crisscross the globe to meet five leaders and thinkers to discuss sustainability, delivering growth, nurturing innovation and the meaning that we derive from our working lives.

Gen Fukushima

CEO, Sanu

It’s a balmy afternoon as Gen Fukushima inspects the greenery dotted around the new headquarters of Sanu, a Tokyo-based company that provides second homes through subscription and co-ownership models. The 37-year-old ceo points out the species endemic to various regions and altitudes, brought together to add a forest-like feel to the ground-floor café, taco stand and event space. The company’s offices upstairs are fitted out with bespoke furniture made from Japanese larch. By bringing together natural elements from far and wide to the Nakameguro neighbourhood, the company wanted to create a place unlike any other. “That’s why we called it Nowhere,” says Fukushima with a smile.

The idea of living with nature has been central to Sanu since its inception. Seeking a new challenge after roles with McKinsey & Company and the Rugby World Cup in Japan, Fukushima founded the company in late 2019 with fellow entrepreneur and outdoor enthusiast Takahiro Homma. Striving to create a nature-focused business without causing harm to the environment, the duo developed a subscription-based service providing exclusive access to their network of villas within several hours’ drive of Japan’s key urban centres. Despite the founders’ purpose-driven ethos, financing proved a challenge at first. “We were confronted by the fact that sustainable and regenerative approaches didn’t translate into funding,” he says. “The reality was that, for Sanu’s approach to be acceptable, it needed to have economic benefits and profitability.”

To overcome this, Fukushima and his team sought to demonstrate that there was a viable market. Harnessing the power of social media, they gathered a small group of members for the initial launch of five villas in two locations. “We think of our first members as a community of people working with us to change society,” says Fukushima. This approach paved the way for financial backing from the likes of property company Mitsui Fudosan and venture-capital firms Goldwin Play Earth Fund and Mizuho Capital. The members established connections through frequent visits, providing insights and introductions that aided the company’s growth.

Launched during the pandemic, amid rising discussions around remote work, mobility and the urban-rural divide, Sanu’s second-home service has gained momentum, demonstrating the value of catering to the needs of nature-seeking urbanites. The company has attracted ¥12bn (€77m) in funding and thousands-strong waiting lists. Plans are under way for 200 villas across 30 sites by the end of 2025, with a view to international expansion in the future.

In the face of this interest, Sanu has remained committed to being a role model for regenerative business, planting trees on its sites and sourcing timber locally. “There was the idea that it would be more efficient to generate wealth, then circulate it back into sustainable initiatives,” says Fukushima. “But during that process, a company can lose sight of its motives. To have a positive effect, principles need to be built into the roots of the business. From the outset, we operated Sanu based on the pillars of business, creativity and sustainability.”

In a year when Sanu has achieved B Corp certification and a new co-ownership project sell-out, Fukushima is excited by the prospect of forging deeper connections through the newly opened headquarters. “Integrity is essential to what we do,” he says. “I could have said being an entrepreneur is about dreams, curiosity or persistence. But in the end, it’s about someone who changes lives, brings people together and has an impact on society.”

sa-nu.com

2010

Joins McKinsey & Company, working on strategic planning, government projects and green energy.

2015

Founding member of Sunwolves rugby team. Works on 2019 Rugby World Cup.

2017

Joins Backpackers’ Japan as a non-executive director.

2019

Sets up Sanu with Takahiro Homma.

Zanele Kumalo

Curator, Design Week South Africa

Zanele Kumalo, who started her career as a magazine editor, is now one of South Africa’s savviest tastemakers and entrepreneurs. After shifting her focus away from the media industry, she launched a content studio and joined Kalashnikovv Gallery in Johannesburg as associate director. Now she has added a new role to her CV: curator for the newly launched Design Week South Africa, which ran in Cape Town and Johannesburg in October. Here, she shares some tips on how creatives can get ahead in the country’s design scene.

Why did you decide to get involved in Design Week South Africa?

When I worked in magazines, I tried to amplify voices that weren’t usually given much space. What drives me now is helping young creatives find a firmer footing in places where they haven’t had access. There’s a wealth of talent in this country. Highlighting creatives makes me happy.

What advice would you give someone seeking a break in the design scene?

Start with commitment and dedication to your skill and story. To “put yourself in the room”, make sure that your product or service is the best quality. This will spur word of mouth. Make it easy to be discovered. Spend time immersing yourself in the industry: go to expos, talks and workshops, check out showrooms, ask questions and read publications that are connected to different industries. Understand how you can connect with diverse brands. The more people get to know you, the more they’ll give you opportunities or offer you information that will help you understand the market.

How easy is it to set up a design business in South Africa?

There aren’t many legal obstacles if you want to set up something quickly. Starting a new business is encouraged and there has always been an entrepreneurial spirit here, especially at the moment because youth unemployment is quite high. We were so closed during apartheid, blocked from importing a lot of things, that we built a healthy manufacturing system. When the country opened up, things changed and factories closed but there has since been a rebirth and reinvigoration when it comes to pride in local produce.

How important is branding?

If you don’t get it right at the start, it can be very detrimental. It’s not just about aesthetics; it’s about who you are and what you represent. It’s your first opportunity to impress people and you can always make tweaks down the line.

What are the biggest challenges facing South Africa’s design scene?Sustainability is difficult for many emerging businesses, as is maintaining quality. Getting your hands on the best materials can be so expensive. Production can also be hard to scale up. My advice is to collaborate: find a peer or mentor who you respect and admire, and who might have been in the game for a little longer than you have.

How will Design Week South Africa affect the local scene?

What’s interesting about it is that, while other expos usually ask those who want to exhibit to pay for a booth, there’s no barrier to entry here. People can also enjoy design in a way that feels more accessible. Instead of taking place in a single space, it’s spread across cities, so it presents a different kind of opportunity for the ordinary person on the street – you might walk into a restaurant and find a pop-up or panel discussion going on. The event is also an opportunity to amplify designers and give them a greater platform to share their brand internationally and create more sales.

designweeksouthafrica.co

2007

Becomes beauty editor and bureau chief at Elle SA.

2016

Opens dim sum bar Town with four co-owners.

2017-2019

Serves as a judge for the 100% Design SA award.

2023

Joins Kalashnikovv Gallery as associate director.

Vorravit Siripark

CEO and founder, Pañpuri

Across Pañpuri’s range of hand creams, face cleansers and perfume oils, Andaman Sails is its bestselling scent. A blend of bergamot, green tea and moringa oil, it’s named after the sun-drenched sea that laps the southwestern coast of Thailand, the brand’s home market.

Vorravit Siripark founded the Bangkok-based fragrance and skincare company in 2003 and more than two decades later – buoyed by the aroma of Andaman Sails, along with some savvy decision making – it is winning market share from both international beauty giants and the domestic competition. “I can comfortably say that we have become the number one brand in our segment,” says Siripark, who is all smiles following a recent business trip to Japan.

At the end of this year, Siripark expects to announce a new partner that will help him to take the company to what he calls the “next level”. Annual revenues are forecast to exceed thb1bn (€27m) for the first time and the company is expanding across Asia, which is the largest beauty market in the world.

The brand’s first Hong Kong shop opened in August. It will open an outpost in Singapore next year and in mainland China in 2026 – proof that international shoppers are willing to pay a premium for Thai products. “The tide has turned,” says Siripark, who talks to monocle at Pañpuri’s flagship wellness spa in the Thai capital, close to where he opened his first tiny shop with personal savings and seed capital from his brother and sister.

The 47-year-old never really set out to be an entrepreneur. He chose management consultancy – a career that took him around the world, including a stint in New York – because it sounded more fun than investment banking. Returning home after obtaining a master’s degree in luxury goods management in Milan, he spotted a gap in the market: Thailand was known for wellness but the best hotel spas in Bangkok only used foreign products. “We don’t really have that many luxury brands coming from Thailand,” he says. “I want to build a legacy for Thailand that lasts and doesn’t just rely on me alone.”

This purpose and passion – two of his three guiding principles – have driven him ever since (his third “P” is people). Siripark credits the company’s current success to the decision that he made in 2018 to bring in a Thai private-equity firm. Lakeshore Capital’s investment enabled Pañpuri to recruit the best senior management from international brands and transform an owner-operated family business into a more professional company. “You need a good team to help you excel – to expand and to grow,” he says.

This injection of fresh capital, industry knowledge and best practice laid the foundations for a series of tough calls during the coronavirus pandemic that are now paying dividends. Chief among them was investing in physical retail, which accounts for the vast majority of sales. Money was spent on larger spaces with unique designs that could deliver the full brand experience.

“We focused on the quality of every shop and realised that we don’t have to be everywhere,” says Siripark, who plans to mirror this success overseas by moving away from department-store concessions run by third parties. “We have learnt along the way that to control quality, especially for a luxury brand, the distributor model might not be the right approach.”

Lakeshore will soon exit its investment but Siripark is in it for the long run. He and his siblings still control the majority of shares in the company and purpose still drives him in everything that he does. “Building a luxury brand is like running a marathon,” he says. “You need perseverance and patience – and when you think that the finish line is near, the race just keeps on going.” Pañpuri certainly has the wind behind it as its signature scent sets sail for the rest of Asia.

panpuri.com

2003

Pañpuri founded in Bangkok with Siamese Water Milk Bath and Body Oil.

2004

First retail concession in Bangkok.

2011

Pañpuri candle wins Japan’s Good Design Award.

2017

Launch of most popular scent, Andaman Sails.

2024

Hong Kong retail debut with scent Heaven Moon Osmanthus.

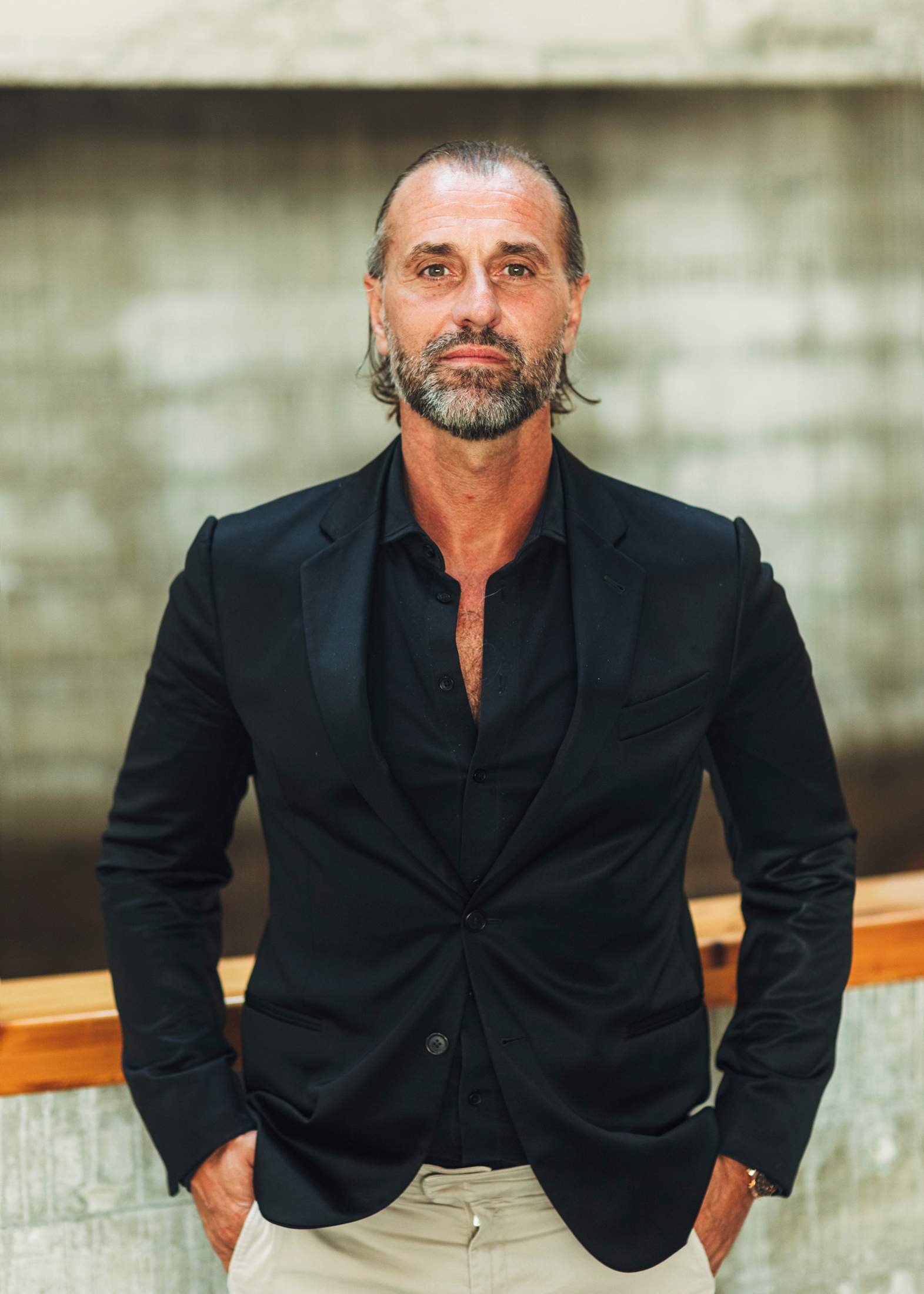

Morten Albaek

Philosopher and author

According to Danish philosopher Morten Albaek, the pursuit of a work-life balance is unwise. The founder of business consulting firm Voluntãs, which has more than 100 staff worldwide, instead believes that we should be seeking meaning and a sense of belonging in all that we do – and that requires taking life as a whole. monocle met Albaek at Unleashed, a Nordic summit organised by Stockholm’s handelskammare (chamber of commerce), and quizzed him about the region’s potential, why he believes that corporate success is easy and how to do work that matters.

People often think of Nordic nations in terms of how happy they are – which they seem to be, according to the data. But you believe that there’s a better way of looking at how people’s lives, including their experiences of work, are unfolding in this region and beyond. Could you tell us about it?

First, we need to decide what we want to achieve. Do we want cities and societies that are happy because they are satisfying most of their citizens’ needs? Or do we want to create meaningful societies and cities? If it’s the former, the Nordics are doing well – on a misguided metric. But if it’s the latter, the countries in the region have quite a journey to undertake. Look at the Nordics from a meaningfulness perspective and dive deeper into their labour markets, and you’ll see that we aren’t among the frontrunners. We’re among the average-to-poor performers.

So what’s happening?

It’s important to understand the definitions of satisfaction, happiness and meaning. People feel a sense of meaning when they stand in the now, reflect upon the life that they live and, regardless of whether what they see is positive, negative or neutral, look forward to what lies ahead. If you research labour markets in the Nordics – and globally too – you’ll see the conditions that have to be in place for a person to find meaning in their life and the work that they do. They need to experience four things at the same time: purpose, personal growth, a sense of leadership and belonging.

In terms of those four drivers, the Nordics are below the global average. Indians, Mexicans and Kenyans find going to work more meaningful than Swedes, Norwegians or Danes do. That might sound pretty absurd but it’s what the data is showing us. So, of course, people have been searching for explanations. Is it because workers in the Nordic region are lacking purpose? No, not at all. We derive a significant amount of purpose from our jobs. But what we are missing here is a sense of belonging.

My hypothesis is that we are seeing the same challenge across Nordic civilisation that we’re seeing in the labour market: we are losing our sense of belonging. The interesting thing is that everybody agrees that if you don’t belong somewhere, you are lost. You need to belong to a family and a community, and you also need to feel that you belong at your workplace. But if you were to ask how many Nordic corporations or municipalities measure this sense of belonging, you’ll learn that the answer is none. To create cities and societies in this region that are existentially superior, we must understand that we are currently facing the deterioration of meaning among those who live here.

What is stopping people from finding this sense of belonging?

If you don’t believe that the life awaiting you will be a more dignified one than what you have today – that the future is more hopeful than the present – you won’t find any meaning in your life. And in the Nordics, we are probably less hopeful than we once were, though the data set to show this didn’t exist 20 years ago because my colleagues and I were the first to create it. Adults aged between 25 and 34 are struggling to find meaning in life and at work. That brings me to another thing that’s very important, probably the most astonishing thing that we have discovered in our research. Globally, an average of 49 per cent of the total meaning of life for working people comes from the jobs that they do. In Sweden, that figure is 37 per cent but, in the Nordics overall, 39 per cent of people’s ability to derive meaning in their life comes from the fact that they find their work meaningful. That fundamentally kills off the idea of a “work-life balance”.

On this topic, you have argued that you’ve got one life and that you need all of its aspects to be aligned – your work and your everyday life should be considered in the same breath.

Yes, if 49 per cent of the meaning of your life, on average, comes from whether your work is meaningful, how can you ever talk about dividing your life and work?

Should you only do work that is meaningful or is it the role of businesses or governments to think about how they can add a sense of significance to people’s lives?

Government is the last resort in this part of the world. To go back to the Nordic average, if approximately 40 per cent of the meaning of people’s lives comes from work, corporations and organisations that employ them have a responsibility to ensure that they organise and design their leadership and work processes in a way that doesn’t lessen meaning – but instead provides it. Again, what’s essential to meaning is a sense of belonging, personal growth, leadership and purpose. We have been doing our survey in different organisations for almost a decade and our global study for five consecutive years, so the data pool is getting bigger and bigger. And what is the most important contributor to meaning at work? You might assume that it’s leadership but that’s the least important factor because it can never instil meaning in the employee’s life.

A leader is a facilitator, meaning that his or her responsibility is to provide space for a sense of belonging, purpose and personal growth. Leadership is not about being a divine figure who enters the room and suddenly everything is meaningful. Instead, it’s a matter of whether you foster an environment in which people can feel that they belong and can be who they are. You don’t have to dress up and you don’t have to dress down. You don’t need to change your language or abide by norms that don’t ring true to you. And you don’t have to say things that you don’t believe. You find the purpose in what you do and you see it contribute both to your life and to a greater good. So the leader is not even a servant – just a facilitator.

You are a philosopher but you have also worked in big organisations. Was that important in developing these ideas about the world and work?

Since Kafka, there haven’t been many intellectuals, let alone philosophers, who have been so deeply involved in multinational, commercial, capitalistic organisations as I have. I spent 15 years as a philosopher, studying the capitalistic commercial system from the inside. I climbed the career ladder so aggressively because it was so simplistically primitive, so one-dimensional.

We have to understand that, ultimately, business has no complexity. It’s just about the need to control cost by ensuring that sales are higher – that’s it. You might tell me that you also need a great idea. Yes, most companies were founded by somebody who had a great idea and is no longer around. A lot of managers are just custodians of a business created, say, 100 years ago and they just do the two things that I said. That’s why it’s fairly easy to get a seat at the high table. The only thing that you need to say is, “I will now show you how you can reduce your costs and increase your earnings. Do you want to listen?”

But if I were to say, “I’ll tell you how I’m going to increase your employees’ quality of life,” the bosses would be afraid that I was suggesting that they should all do some yoga. When we enter the room, it’s with an acceptance of the capitalistic system. We just want to transform it into a humanistic version of that.

But you don’t question clients’ desire to make a healthy profit?

I want to prove – and, in fact, have proven – that you can earn more money, more quickly, by providing your employees with a higher quality of life and increasing their sense of meaning.

Finally, what are the things that you need to do as a company to start thinking about meaningfulness?

You have to understand and accept the differences between meaning, satisfaction and happiness. If you don’t do that, you will be wasting your own time – and certainly mine. Second, you must make clear what your company is and what you want it to be. How can people know whether it would be meaningful for them to work there if you have not been crystal clear about who you are and who you want to become? Then you need to make your vision of your culture scalable, bring that manifesto into your business processes and gather data. You should measure what you treasure and your organisation’s sense of meaning. Alternatively, you could just continue doing what you’re doing: you might get rich but you’ll just be repeating the capitalistic models of the past and not improving the life quality of those who work for you.

Morten Albaek is the author of several books, including ‘One Life’. His latest, ‘Falske Sandheder i Livet’ (The False Truths We Live By), topped the bestseller lists in Denmark and will soon be published internationally.

Chiara de Iulis Pepe

Head of wines, Emidio Pepe

An early pioneer of low-intervention methods, 92-year-old Emidio Pepe is among the most respected names in natural wine. This year his vineyard in Italy’s Abruzzo region is celebrating its 60th anniversary. Its head of wines is Emidio’s 31-year-old granddaughter, Chiara de Iulis Pepe, who studied business at the Sorbonne and winemaking in Bourgogne. While she is carrying on her grandfather’s traditions – grapes picked by hand and pressed by feet, and wine refined by long ageing processes – she is also applying an entrepreneurial mindset and pioneering new techniques to address climate-change-related challenges. By raising Emidio Pepe’s profile, she has elevated the reputation of natural wine among connoisseurs. Meanwhile, her sustainable practices are inspiring even large-scale producers as changing environmental conditions impact vineyards of every size.

How do you change natural wine’s image to move it beyond its status as a niche product?

There are many misconceptions about natural wine – that it has defects, that it can’t be elegant, that it can’t be aged because it doesn’t have a lot of added sulphites. That’s why I don’t use the term “natural wine”. I prefer simply to explain our ethics and how we work: with biodynamic farming, manual handling of grapes, strictly indigenous yeasts and long ageing processes.

How did you rethink Emidio Pepe’s approach to sales?

We stopped doing the big wine fairs. Convention centres are not the right venue for talking about high-level wines produced with such care and craft. Now we bring buyers to us in Abruzzo. We show them the vineyards and how we take care of our land and our wines. Our communication strategy is very time-consuming but it provides a truer portrait of our product.

As an artisan producer of wines, how do you grow the business?

We can’t boost production so we’re increasing the ageing of our wines, which gives them more value. I’m building a new cellar to allow us to age more bottles. It’s an economic model that’s very different from the wider wine world’s approach of simply maximising quantities.

What challenges do you face as the third generation helming the winery?

When my grandfather was starting out, his neighbours thought that his ideas about ageing Montepulciano wines – and of manual and chemical-free agriculture – were crazy. He was very forward-thinking. I need to be the same way when it comes to dealing with global warming. Making top-level wines in a changing climate is a challenge. My generation faces weather conditions that aren’t predictable or cyclical. If I want to continue making wines for the next 30 years, I need to take important steps in the next three or four years.

How did you shake things up when you came on board in 2020?

The biggest things involved dealing with climate change: planting vines in new locations, adding water reservoirs and shade. I also devised an agroforestry technique in which grapevine rows are lined by trees and protected by their shade. It’s called the Pepe Pergola.

Some major wineries are starting to incorporate natural practices. What can they learn from you?

They need to recognise that monoculture must end, with a return to biodiversity on farms, and that spraying the soil with chemicals only brings us closer to the desertification of our farmlands. They have to stop growing only what they can sell and start thinking about being custodians for their piece of earth.

emidiopepe.com

1964

The Emidio Pepe winery is founded, using chemical-free and manual farming from the start.

2005

The winery converts to biodynamic farming.

2020

Chiara De Iulis Pepe, age 27, takes over the winemaking and vineyards.

2022

She introduces the tree-shaded Pepe Pergola method of vine-growing.