Affairs: Interview / Greece

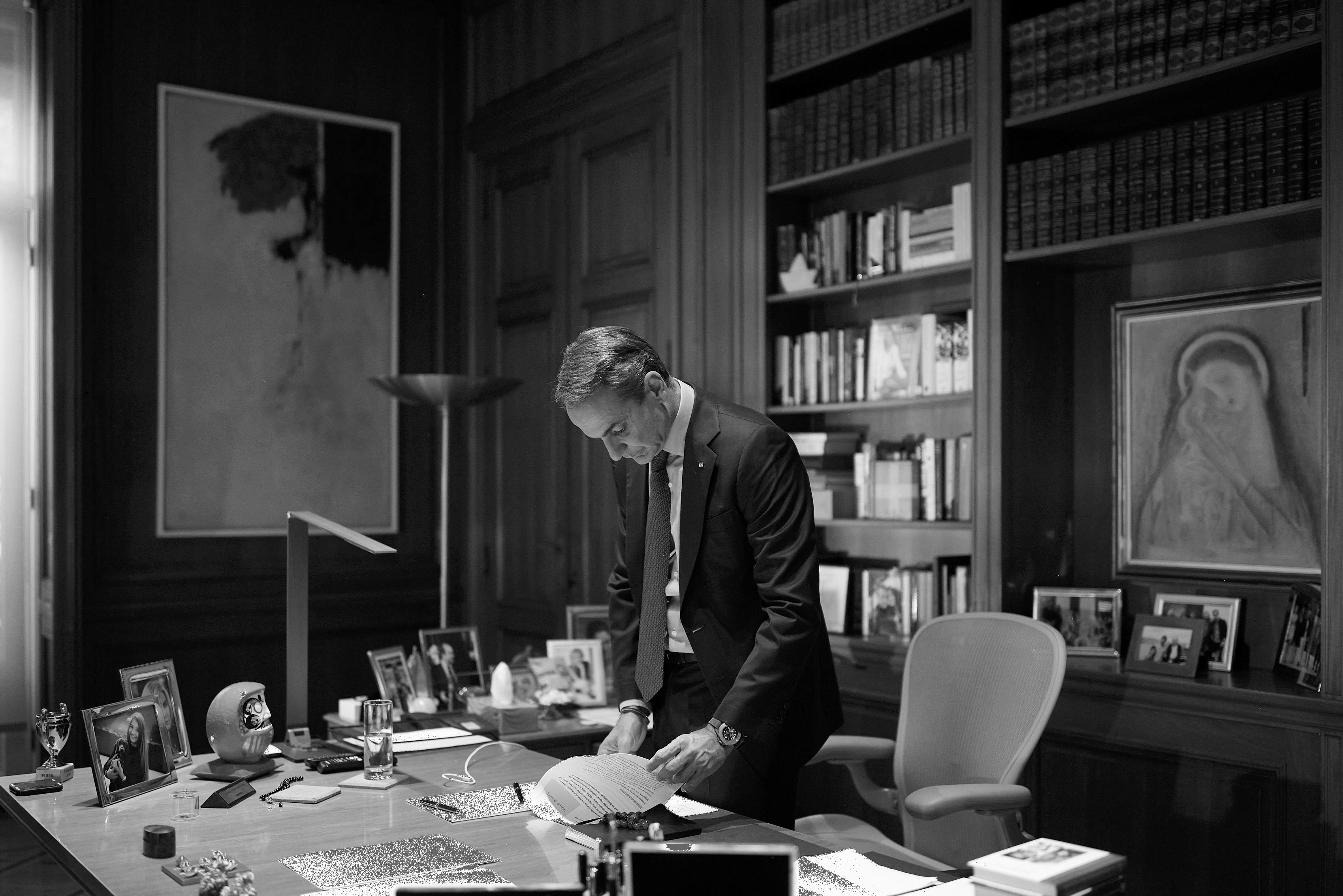

Centre stage

Now well into his second term in office, Greece’s prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, tells us about re-establishing moderate, modernising politics in the country and how Athens can wield influence in Europe and beyond.

Kyriakos Mitsotakis is a member of the club of political leaders who have won two elections in the same calendar year – indeed, in his case, inside five weeks. In May 2023, Mitsotakis’s centre-right New Democracy party (ND), in power since 2019, was not quite re-elected. It won the most seats in the Hellenic Parliament but fell just short of an outright majority. Mitsotakis, fancying his chances under a revised electoral system, called for another election in June 2023 and nabbed ND the majority that it needed to govern.

This apparent embrace of centrist pragmatism by Greece seemed colossally unlikely as recently as a decade ago. Greece was devastated by the European debt crisis of 2009. The national economy was reduced by a quarter. Unemployment cleared 25 per cent; nearer 60 per cent for those under 25. Perhaps 500,000 people – about one Greek in 20 – left the country. Among those who stayed, there was ready appetite for the theory that three monumental bailouts from the EU and/or the imf, and the brutal austerity measures attached, were more part of the problem than they were of any solution.

Greece embraced populism in 2015, when two elections that year established an unlikely coalition between the left-wing Syriza party and the right-wing Independent Greeks. The results of introducing their ideas to reality were such that by 2019, Greece was willing to deliver a landslide to Mitsotakis, an establishment archetype – a Harvard Business School mba, a former banker and consultant, and scion of a Greek political dynasty. Mitsotakis’s father, Konstantinos, was prime minister in the early 1990s; his sister, Dora Bakoyannis, foreign minister from 2006 to 2009; his nephew, Kostas Bakoyannis, mayor of Athens from 2019 to 2023.

monocle sits down with Mitsotakis at the 2024 Munich Security Conference. —

M: In February 2024 you steered the legalisation of same-sex marriage through Greece’s parliament. That was a first for an Orthodox Christian country – and not an easy win. Why now? Was it one of those things where you think in a couple of years nobody will remember why they were angry about it?

KM: I’m very happy and very privileged that as the leader of a centre-right conservative – but also progressive – party, we were the ones who brought this piece of legislation in front of parliament and got it through with a very strong majority. I’m also happy because we had the opportunity to explain to Greek society what this bill is really all about. For the first time, we actually heard from those who are deeply affected by the fact that marriage equality was not recognised in Greece. I even told my parliamentary group something that another conservative had said – that marriage, at the end of the day, is a conservative institution and I’m voting for this not in spite of being a conservative but because I’m a conservative. And I can say that the level of public debate was very mature. I think public opinion has swung in support of this legislation but we treated those who disagreed with great respect. Within my party, I never used the whip – our MPs chose freely and I’m happy that more than two thirds [of parliament] ended up supporting the bill.

ON POLICY

“I’m privileged that, as the leader of a centre-right party, we were the ones who brought same-sex marriage legislation in front of parliament and got it through”

“We’ve had to deal with the past decade, which robbed us of a quarter of our GDP, and we are gradually catching up”

M: Did you see this as an isolated act of progress or does it fit into a broader programme of rebuilding, reconstruction – even modernisation – of Greece, versus where you were 10 or 12 years ago in the depths of the debt crisis?

KM: Oh, very much the latter. I’ve made my second term about what I call a multi-dimensional modernisation programme. This includes issues related to human rights but extends way beyond that. My goal has always been to make Greece a true European country – and why not surpass the European average in those indices where we can be a protagonist? So this is a long-term programme. We’ve had to deal with the past decade, which robbed us of a quarter of our gdp, and we are gradually catching up, though we need to accelerate the pace of growth. At the end of the day, it is about growth – but it is also about equitable growth. That’s why I focus so much on making sure that our policies are just and that the wealth we create is spread evenly. So my focus is on wages, on improving the minimum wage and improving the average wage. I’ve set very clear targets about what I want to achieve over the next four years – and we’re on track to reach those targets.

M: Were you surprised, then, when the EU parliament took a bit of a swing at Greece [in a resolution on 7 February on the rule of law and media freedom in Greece]? It’s non-binding but nonetheless very critical of backsliding on rule of law and press freedom. Greece does have the lowest ranking of any EU country in the World Press Freedom index too. Are these areas where work still needs to be done?

KM: May I be a little bit blunt? This report is a joke. It puts Greece under [some] African dictatorships in terms of press freedom. Anybody who has travelled to Greece and taken a look at our media landscape knows that we have the highest number of radio stations in Europe [per capita], a very vibrant TV scene, lots of newspapers, most of which criticise the government. I’m not saying we’re perfect but I am saying that the European Parliament report was bogus and only the result of a deeply politicised European Parliament that simply wanted to take a swing at a very strong party within the epp [European People’s Party] family.

At the end of the day, the gold standard in terms of rule-of-law classification is that annual report by the European Commission. They are the guardians of the rule of law; they pass the final judgement. And [in that] we have been improving. Yes, there are issues that we need to address. Justice needs to move faster. There are issues raised by the rule-of-law report regarding the ability of journalists to operate in Greece. We think that there is ample room for them to do their job but we will take their recommendations very seriously. But, sorry, we’re talking about a politicised report by the European Parliament that is full of accusations which are not true. It was a political act.

M: Nevertheless, was the scandal attending the bugging of phones by Greece’s intelligence service, the eyp, not something of a wake-up call? They were tapping journalists, politicians, officials, at least one bishop. Did that suggest to you that some aspects of the state had gone a bit haywire?

KM: I acknowledge that mistakes were made. And what, for example, was not mentioned in that European Parliament report was that we actually changed the law; we passed a very tight system regarding lawful surveillance. And we’ve also gone very hard in terms of making sure that any unlawful surveillance software cannot be sold or operated. Of course, it was a wake-up call, and we acknowledge the mistake. But what I cannot accept is the fact that no one is acknowledging that we’ve made progress on that front – or at least the European Parliament isn’t; the Commission has acknowledged that progress has been made. But this was not just a Greek problem – and I really don’t understand why when Spain was facing similar problems, no one was raising them, yet the finger was pointed at Greece.

Having said that, I will continue to work for a well-functioning democracy that is inclusive – and our track record supports the idea that we have made progress on that front. In elections last year, we were re-elected to power with an overwhelming majority. And I’m unapologetic about being a moderate, centrist politician. And I don’t think you would expect someone who does not define themselves as a centrist politician leading a centre-right party to legislate marriage equality. I mean, these are not the sort of things that the hard-right politicians of this world do.

On press freedom

“Greece has the highest number of radio stations in Europe, a very vibrant TV scene, lots of newspapers”

“We’ve gone hard in terms of making sure that unlawful surveillance software cannot be sold or operated”

M: Does Greece need to take its own defence more seriously, especially at sea? For all that it’s a smallish country, it controls 21 per cent of the global merchant fleet in terms of tonnage, which is an extraordinary statistic. Greek-owned or Greek-operated ships have been attacked by the Houthis in the Red Sea. We know that one Hellenic Navy frigate has been dispatched, though we believe that it doesn’t have anti-ballistic capacity. Does Greece need to become more of a naval power commensurate with its status as a great maritime nation?

KM: First of all, let me point out that Greece is spending 3 per cent of its gdp on defence. And we have been consistently above the 2 per cent Nato threshold even during the very difficult years of the economic crisis. The reason was simple: there was never a peace dividend in Greece, as we always faced a larger, occasionally rather aggressive neighbour. We felt that we always needed a credible deterrence capability, and we will, of course, continue to do so. That is not true for many other European countries. And I think that, as Europe, we are paying the price now of under-investing consistently in our defence capabilities.

Now, you’re right to point out that the Greek merchant fleet is a global powerhouse. And that is why we never shied away from our responsibility to protect freedom of navigation and why we will be having a presence – a ship will sail very soon, fully equipped with all the necessary technology to protect itself, and it will go to the Red Sea. And we are also the ones assuming control of the European operation Aspides, meaning “shields”, which works in conjunction with Operation Prosperity Guardian in the Red Sea.

Now in terms of strengthening our navy, we have a rather capable navy but we’re also investing heavily in terms of upgrading our naval capabilities. The first of the three ultra-modern frigates we ordered from France will be arriving. It’s already at sea; it will be part of the Greek navy next year. And, of course, we’re looking at the future of naval deterrence, including unmanned ships and submarines. So what we want to do is to make sure that, as a big spender on defence, we also develop our own technological capabilities. But this isn’t just relevant for Greece; it’s also relevant for Europe. I fully agree with the comments made by [European Commission president] Ursula von der Leyen that we will need to spend more on defence. But we also need to be smarter about when we spend on defence. There is still very little joint procurement, there is still a colossal fragmentation of the defence industry in Europe and, regardless of what happens in the US, the Ukraine war should have been – and is, to a certain extent – a wake-up call, from the big projects such as air defence to the mundane issues of producing enough shells for artillery, which many people didn’t think necessary but proves to be indispensable in a prolonged ground war.

on defence

“There was never a peace dividend in Greece, as we always faced a larger, occasionally rather aggressive neighbour”

“There is still a colossal fragmentation of the defence industry in Europe, and the Ukraine war should have been a wake-up call”

M: There is, of course, a frequently volatile region immediately to Greece’s north. Would it not contribute to the security of the Balkans if Kosovo felt surer of its place in the world? And would Greek recognition of Kosovo’s independence not help with that?

KM: We have been proponents of the European path of the Western Balkans since what we call the Thessaloniki Declaration back in 2003. So it has been 21 years. And since then we have not made as much progress as we would like. But the Ukraine war has brought the issue of European enlargement again to the forefront. Now, we’ve been very, very clear in terms of trying to facilitate the dialogue between Pristina and Belgrade. And we’ve also been very frank with both. I’ve been frank – I was recently visiting President Vucic [of Serbia], I saw Albin Kurti [prime minister of Kosovo] and I have very good relations with them. Both need to take a step back at some point and stop pointing fingers at each other if we want to make some real progress. But Greece’s position for the foreseeable future is not going to change.

M: You were talking earlier about what you’ve been able to accomplish as a nominally centre-right politician. Against the backdrop of what has been tried in Greece and elsewhere in Europe since the economic crisis, many countries have wondered how to tackle populism, which does tend to peak at moments of crisis, often insisting that there are simple solutions to complex problems. But however often the populists are proved wrong, they never quite die out. Is any part of your programme exportable? Is there a cure for populism?

KM: I don’t think there is a general template for combating populism – and all political systems have their own peculiarities and their own electoral laws. In our case, we’ve been able to form a single-party government, whereas in other countries coalitions are a necessity. But maybe I have a few thoughts to share on this topic. At the end of the day, you need to understand that the grievances that fuel the populist response are real grievances, whether they have to do with income inequality or with people feeling lost in a globalised world.

M: Do you think they’re always real grievances, though? Aren’t some populist eruptions animated largely by fantasies?

KM: Even if that is the case, grievances related to income inequality are very real – just look at the numbers. At the end of the day, it is usually about the economy. There are people who feel that they have been left behind. I mean, look at farmers – we’ve had farmers protesting in Greece. It’s very easy if you’re living in a big city to say, “Who are these guys with their tractors showing up on our streets if we give them so much support?” But I think that’s a simplistic question. When we looked at the problem in detail, we realised that we needed to do something – for example, about the electricity prices that farmers pay. And we found a solution to give them a better electricity price. Because if they are not competitive, and if they stopped doing what they do, this would create huge consequences, not just for the safety of our food supplies, but also for regional cohesion.

I would say that quite a few of the grievances are real. I’m not talking about the conspiracy theories but there is something there that needs to be

acknowledged. And, you know, there has been enough finger-pointing by the Davos – or Munich Security Conference – elites at those people. And that never works. That attitude of [dismissing people as] “deplorables”, for lack of a better word, is a complete catastrophe.

When it comes to real solutions, what we have done, I call it “the new triangulation”. Be clearly pro-growth, reasonably lower taxes while maintaining fiscal discipline, attract investments, simplify the business environment, create jobs. So a liberal approach on the economy that puts a lot of faith in private entrepreneurship and what I call a “responsible patriotism” approach when it comes to issues of foreign policy. So we were tough with Turkey, we increased the deterrence posture and we managed the migration problem reasonably well. I think this caters well to the more conservative aspect but we can also be rather progressive when it comes to social policy – raising the minimum wage beyond what many people expected, coming up with strategies for those who are less privileged and doing marriage equality.

Now, all of that opens up new possibilities for a moderate centre-right party but we [the New Democracy party] have also had another advantage. Greece actually elected the populists to power. It was a strange alliance of hard-left and hard-right populists, and it was a disaster. People still remember that. But when you’re in your second term, you don’t compete with who was in power five years ago; you have to solve real problems. You have to be honest, you have to acknowledge your mistakes but you still have to deliver. And we are delivering, especially when it comes to the economy. If you do all that, people will give you the benefit of the doubt. In our case, they voted for us again.

on populism

“Grievances that fuel the populist response are real grievances, whether it’s to do with income inequality, or feeling lost in a globalised world”

“Greece actually elected the populists to power. And it was a disaster. People still remember that”

M: Greece’s economy is recovering but how hamstrung are you still by a shortage of workers? You’ve pushed through legislation that will regularise 30,000 unregistered labourers, but how short is Greece of the workforce it needs?

KM: Well, who would have thought that you would be asking me this question five years ago, when we had unemployment that was about 20 per cent? Our unemployment is now about 9 per cent, which is better but it still needs to be addressed, in the same way that we’re now beginning to have a housing problem because property prices are going up. In our case, we have issues in agriculture and we have issues in construction. Occasionally, we have issues in services but the tourism sector is good at finding labour.

So what we’re offering is: in exchange for a policy that actually protects the borders and does not outsource to smugglers the decision regarding who will come into the European Union, we wanted to open legal pathways to migration. So bilateral deals with various countries – for example Egypt, India and Vietnam – that will bring in labour through legal pathways in an organised manner. Also, we want to start offering more tailor-made visas for those who would like to come to Greece. And what we saw during the coronavirus pandemic was that the digital nomads – [some of] the people who read monocle – actually found the idea of setting up shop and working in Greece very interesting, because at the end of the day it is also about quality of life. Greece offers a pretty good proposition when it comes to attracting these kinds of people.

M: Is there something here in terms of tackling populism as well? Populism is very often tied to some sort of paranoia about immigration – do you think that the problem there is not so much that people fear or dislike immigration but that they’re worried about the appearance of disorder, the idea that there’s no programme, nobody in charge?

KM: I think you’re right. But Greece has been in various respects a success story when it comes to integration. Look at, for example, the Albanians who came to Greece in the 1990s. They have second-generation children who were born in Greece; they are Greek citizens, they go to Greek schools; they consider themselves Greek. I would say that it’s a success story overall. And even now – yes, Greece was a relatively homogeneous society, but you learn from people who are different. Probably the best basketball player in the world, Giannis Antetokounmpo, is a Greek of Nigerian origin. He doesn’t look like a traditional Greek but he is Greek at heart and plays for the national team. But you don’t have to be a basketball star for Greece to treat you well.

So the question is, how do you expand this attitude towards those people who want to live in Greece and consider Greece their home – and for those who come to Greece and obtain asylum in Greece. They are welcomed – and they should be welcomed in Greece, because we also have real needs in terms of our labour market. And we are a society, also, of people who have emigrated. So we know something about what it means and how painful it is to leave home in search of a better future. I think we can find the right balance.

For more insights from the Munich Security Conference, plus Monocle’s take on global affairs and diplomacy, listen to our weekly podcast ‘The Foreign Desk’. Or listen to Monocle Radio.