Affairs: India / Bengaluru

Rising tide

In a pivotal election year, India’s strengths and contradictions are rising to the surface in a city touted as its answer to Silicon Valley.

Bengaluru’s flower market

“This is India!” says monocle’s taxi driver, laughing, as his vehicle pulls out of a deep pothole and enters the smooth, tree-lined lanes of Embassy Boulevard, a gated community in the north of Bengaluru (also known as Bangalore). “It’s a bubble but it keeps some of the chaos at bay,” says Jacqueline Chandra, a Swiss-Australian marketing executive who lives here with her Indian ceo husband and their children. Embassy Boulevard’s neatness verges on the banal but, in 21st-century India, such bastions of cookie-cutter monotony are relished for their order. Chandra is typical of the residents of Bengaluru, the capital of India’s southern state of Karnataka, where about half of the population of 13.6 million consists of migrants. Many are expats; most have flocked to this city from across the subcontinent.

Bengaluru was once known as “The Garden City” but is now widely referred to as “India’s Silicon Valley”. Its transformation from a sleepy town full of lush gardens into one of India’s most economically important cities took just a few decades. The southern city has long placed a premium on education and English is widely spoken here. So when US software companies began looking for low-cost skilled workers, it became a natural talent pool from which to draw. The tax incentives and liberalisation of India’s economy in the 1990s provided fertile ground for homegrown companies such as Infosys, Wipro and tcs. Their example attracted multinationals to Bengaluru, which now boasts about 67,000 registered technology companies and 13,000 start-ups, 43 of which are “unicorns” (valued at more than $1bn). It is also home to 13,200 millionaires, a number that is expected to double in the next 10 years. Today, Karnataka contributes 8.2 per cent of India’s gdp.

This sense of economic opportunity is something that many young Indians (half of the country’s population is under 25) are embracing as campaigning intensifies ahead of a pivotal general election. With some 970 million people going to the polls, it will be the world’s largest-ever democratic exercise. Facilitating a vote involving nearly an eighth of the planet’s population is a huge endeavour, which is why the election is staggered over six weeks, from 19 April to 1 June. Unlike in other democracies that enjoy (or endure) long campaigns, in India the candidates aren’t even announced until a month before polling. If there is one city that’s a microcosm of the nation – with hopeful, young voters embracing the idea of a progressive India, while navigating issues such as poor infrastructure and social stigmas – it is Bengaluru.

Ankit Nagori, who moved to the city from New Delhi, is a classic T-shirt-wearing Bengaluru technology ceo. He cut his teeth as chief business officer at Flipkart (India’s answer to Amazon) and now runs Curefoods, a business with 300 takeaway kitchens and 50 restaurants. “The city is a melting pot,” he says. “It’s a place where people with no hang-ups live.” His view is shared by content creator Jharna Kukreja, who moved here from Mumbai 15 years ago and lives in a 10-storey apartment block with a playground for her children. She loves Bengaluru’s progressive attitudes and the way that the “Who’s your daddy?” background check common in India is not as prevalent here. “Unlike in other parts of the country, where you have to come from a certain family, community or background, you don’t have to be someone to access opportunities here,” she says. To Nagori and Kukreja, Bengaluru represents what a successful 21st-century India could be: egalitarian, outward-looking and economically dynamic. However, like the country as a whole, the city faces many obstacles to future success.

This year the effects of water scarcity will be felt more severely than usual, as Karnataka endures its worst drought in 40 years. Inadequate infrastructure is another significant problem. But ask residents to name the worst thing about Bengaluru and you’re likely to get one answer: traffic. It’s heavy and slow-moving at best and a single breakdown can bring it all to a standstill. “The city grew faster than the infrastructure,” says Venkat K Narayana, the ponytailed ceo of Prestige, one of India’s largest developers, who is based in Bengaluru. “It’s a constant catching-up game.” Prestige’s growth exemplifies the long boom that has transformed the country. In the past 30 years, it has completed projects covering a total of 17 million square metres; this year alone it has a further 14 million square metres in the pipeline. Like most business leaders in Bengaluru, Narayana credits the ruling, right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) and its figurehead, prime minister Narendra Modi, with India’s progress. “Growth only happens if there’s infrastructure, stability and consistency,” he says.

But there are increasing concerns that not enough is being done and that if the city can’t get on top of its problems, companies will locate elsewhere. “India is a strange country, ancient and modern at the same time,” Naresh V Narasimhan, principal architect at Venkataramanan Associates, tells monocle. “On one hand, I have designed a high-spec building for Boeing here that the company said was the best of its kind outside the US. And on the other, all you have to do is get out of your car and your leg falls into a ditch of raw sewage.” Narasimhan led the team that transformed the now-bustling Church Street in the heart of Bengaluru from a “rotting, stinking” mess into what he calls “India’s first truly shared pedestrian street”. While some of the city’s other thoroughfares are clean and buzzing, most are cluttered and in disrepair.

Last May the bjp lost the Karnataka state elections and the opposition Indian National Congress (commonly known as the Congress party) is now in charge. This could be viewed as an attempt by voters to send a message to politicians about their perceived slowness in delivering change. While Bengaluru’s rich get richer, its poor swell in number, mostly as a result of an influx of rural workers; the city’s population has grown by about 400,000 a year since 2020. Yet this sort of electoral flip-flopping has gone on for the past decade across the country and many say that it’s a sign of a healthy democracy. Young bjp MP Tejasvi Surya, who naturally would prefer his party to control Karnataka, attributes Bengaluru’s recent advances to the funding and support that it has received from central government. The 33-year-old rattles off a list of these accomplishments, including 75km of new metro rail, a 268km ring road around the city, 1,500 electric buses and even approval for a long-awaited US consulate. “Because of all of these measures, people of Bengaluru have greatly benefitted from the Modi government,” he says. “This is why the city votes overwhelmingly for the bjp.”

He is right that India’s boom town does seem to favour the ruling party. Despite its popularity, however, the bjp has a defensiveness born of the criticism that Modi’s India often receives, both from within the country’s once-dominant left-wing intelligentsia and from observers beyond its borders. For example, the party has been accused of using state institutions to pursue political rivals. In March, Arvind Kejriwal, Delhi’s chief minister, was arrested on corruption charges, resulting in a protest that brought hundreds onto the capital’s streets.

Many also worry that Modi is trying to turn India into a “Hindu Pakistan”, with full rights and protections only given to the Hindu majority. “I fear for India,” says Brijesh Kalappa, a Supreme Court advocate and former Congress party leader. “Decisions to hurt amity among religions will have long-term consequences.” India is home to more than 200 million Muslims, making it the country with the second-largest Muslim population. But they are a minority compared to its 1 billion Hindus. Modi’s project to reclaim pride in Hindu civilisation has unnerved Muslims and revived fears of civil conflict. He has been criticised for condoning interfaith violence as chief minister of Gujarat in 2002, when widespread Islamophobic riots left more than 1,000 people dead. And his decision in January to consecrate a temple in the city of Ayodhya was seen as highly inflammatory: it was built on a sacred Hindu spot but one that is also the site of a 16th-century mosque destroyed in 1992 by Hindu mobs. Like most places in India, Hindus and Muslims live and work side by side in Bengaluru, though none of the Muslim shopkeepers who monocle spoke to were willing to comment on the election.

At Bengaluru’s trendy Third Wave coffee shop, however, a group of young office workers say that they don’t see such divisions in their circles. “I have a lot of Christian and Muslim friends,” says 32-year-old Lakshmi Narayan. “We all live in harmony.” Her 39-year-old colleague Jiban Kumar agrees. “As far as any sectarian discord goes, it’s politics and hype,” he says. “The bjp has made developments for the past 10 years. We have seen no corruption or social disharmony.” This view partly reflects Bengaluru’s ability to move beyond India’s ancient divides towards a more peaceful settlement. But there have been exceptions. On 1 March, a homemade bomb exploded at a vegetarian café during lunch hour, injuring eight people. Many initially tried to underplay its link to terrorism but investigations are pointing to the role of Islamist extremists.

“Fear has permeated the community,” says Tanveer Ahmed, a former spokesperson for secular political party Janata Dal Secular (jds). “The bjp systematically excludes Muslims from holding representative positions. Meanwhile, other parties only allow mostly illiterate or problematic Muslims to lead: individuals who lack education and fail to grasp the complexities of issues or pose challenging questions.” Peculiarly, the jds has now entered into an alliance with the bjp in Karnataka, underscoring not only the elasticity of ideology in India’s politics but also the fact that religious violence – or the threat of it – has become a campaigning tactic for many.

Indeed, most people in Bengaluru only have praise for Modi, his reputation as an antagonist notwithstanding. “Modi is legendary,” says taxi driver Hareesh Kumar, part of a group crowding around a tea stall on a balmy evening. “He’s the one and only gift for India.” MC Shilpacharya, who used to be a goldsmith and now owns his own photocopying shop nearby, agrees. “Because everything is online, Modi has brought digital to India,” he says. Restaurant manager Pradeep Shetty is most impressed by India’s improved standing on the world stage. “Since Modi came to power, everyone knows us,” he says. “He’s doing very good things for the country.”

Unlike in many Indian cities, where people chew over the endless horse-trading of coalition politics, Bengaluru’s business and start-up communities tend to look at politics through a cost-benefit lens. When the going’s good, few want a regime change. Whether Modi is good for India is a touchy subject for the venture capitalists who monocle meets in a smart building off Church Street. Between conversations, their attention flits to the large, muted cnbc screen – the trademark twitch of 21st-century moneymen.

Karl Mehta is a foreign investor of Indian origin who feels that the West has the wrong idea about the country. “It views nationalism as a negative word because of the trauma of Hitler,” he says. “But being nation first isn’t a bad thing. The US is nation first and nobody questions it. The West doesn’t understand India. We’re a 5,000-year-old civilisation. But for the past millennium, we have been told that our culture and traditions are inferior. Now, India feels proud of its identity.” At a time when the old powers of Europe and the West are failing to get their way on the international stage, the bjp is the party for those trying to shake off the last of India’s postcolonial grievances, a potent attribute in this city of young companies.

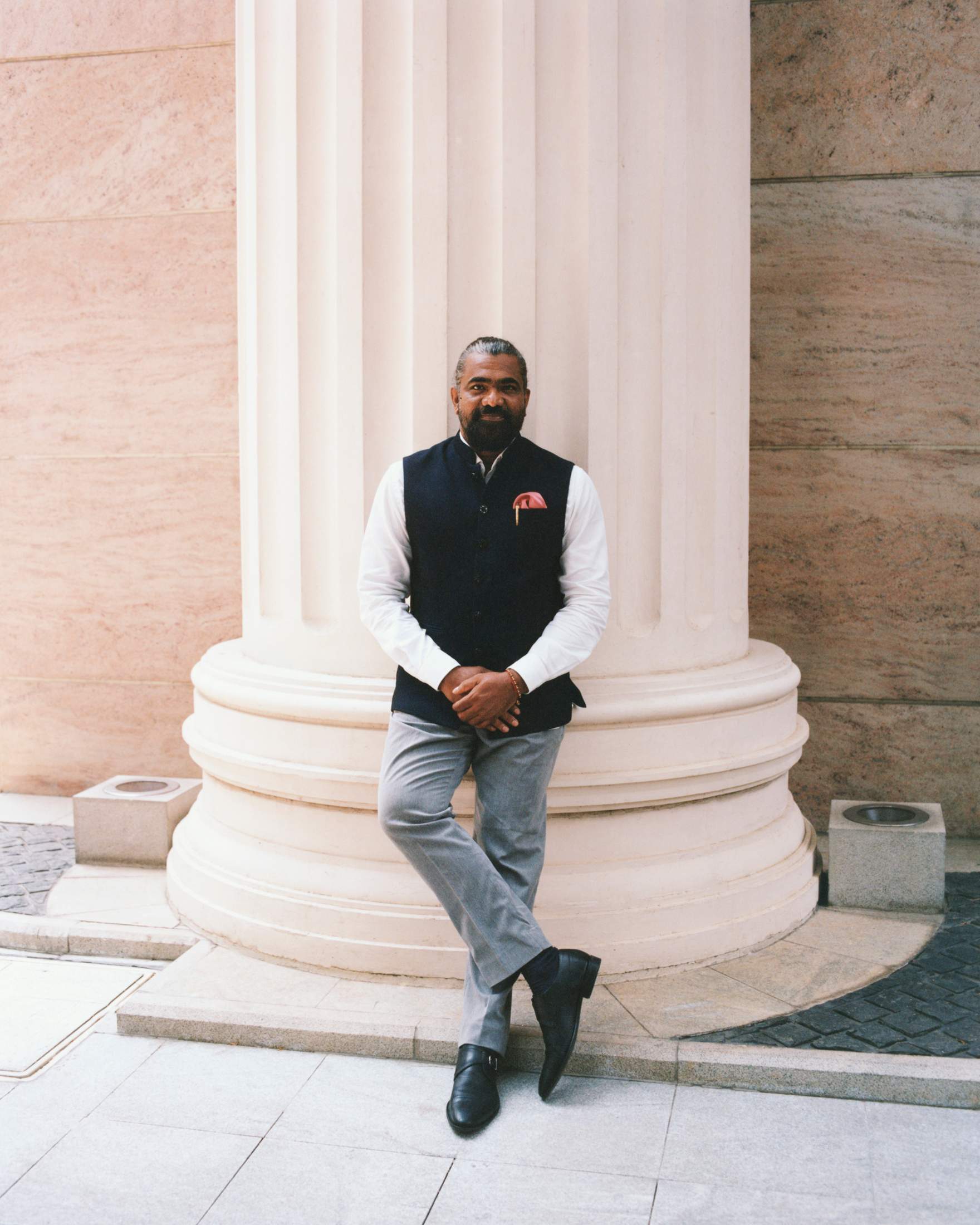

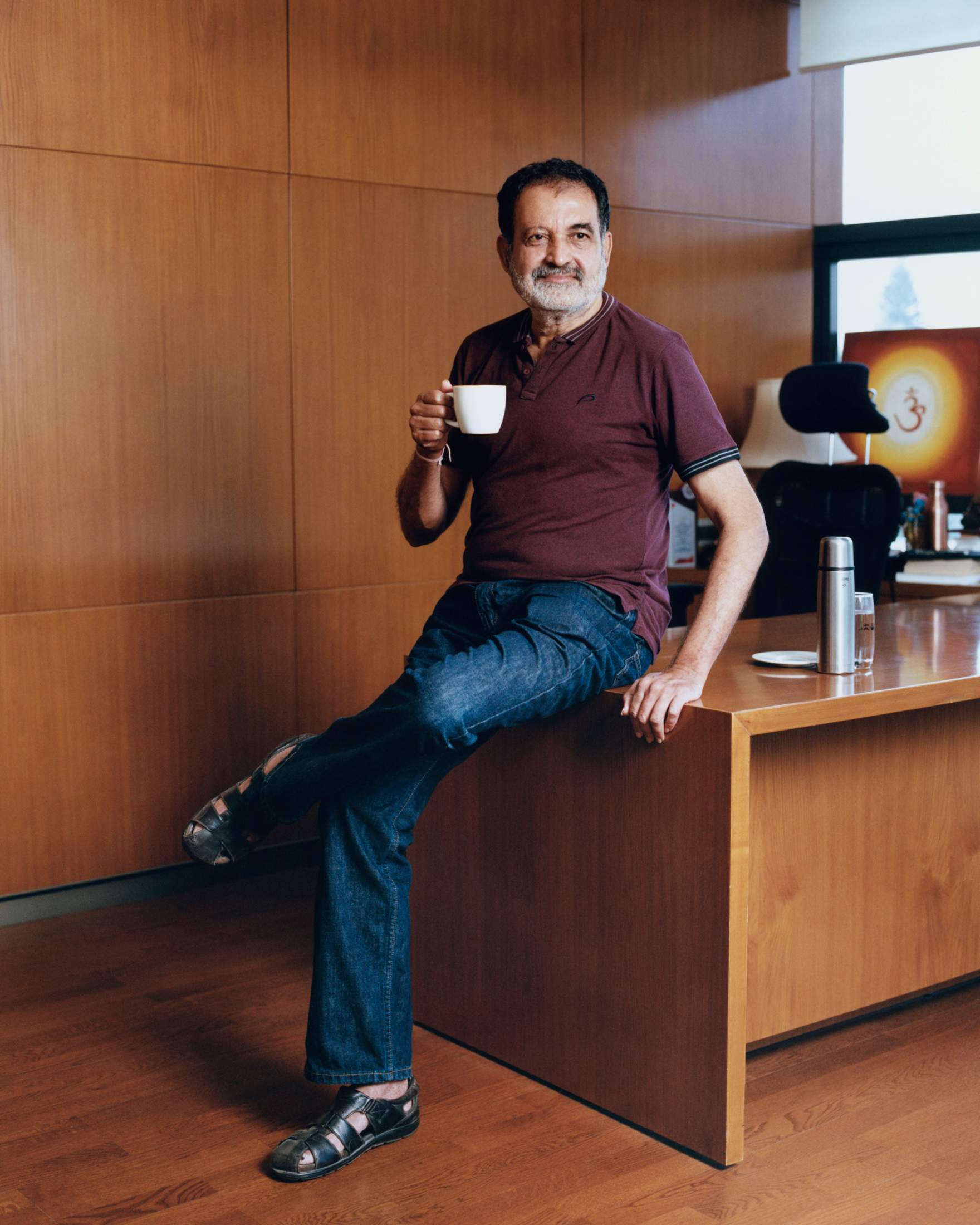

There are more Indians than ever with no direct connection to British colonial rule, which ended with independence in 1947, or the decades of socialism that followed it. Of the nearly one billion eligible voters in this election, more than 550 million are under the age of 40. Their worldview developed after 1991, when India’s markets opened to foreign capital. Within a few years, hundreds of millions of Indians suddenly gained access to a wideing machines and laptops) to the modish (Adidas and Armani). Smartphones and digitisation increased financial inclusion. Very poor Indians, who for centuries had been at the mercy of ruthless moneylenders, could instead procure loans directly from banks. Middle-class shopkeepers, used to keeping cash stuffed in mattresses, can now invest in stocks and bonds more easily. “They don’t know much about the freedom movement or Gandhi,” says TV Mohandas Pai, a Zen-like 65-year-old investor and philanthropist. “They’re not bothered. They’re not beaten people who believe in the superiority of the white man. They’re seeing India growing, especially under Modi.”

Pai made a name for himself as a former board member and cfo of Infosys, one of India’s behemothic IT firms. “Modi is in a strong position because most Indians are poor,” he says. “What has he done? He has put roofs over their heads and given them toilets, mobile phones, food and medical help. And he has never backed down on Pakistan or China.” Pai rails against what he calls the “anti-Modi ecosystem” that wants to “save India from itself”, especially when it is fuelled by Indians who live abroad. “Liberalism is making sure that there are multiple voices,” he says. “But I know of people who have said positive things about Modi, then been cancelled. The only ones complaining are those who were kicked out of power or economic refugees who left India. We stayed and built the country. Not the malcontents. We don’t need them. India will stand up for itself.” Conspiracy theorists suggest that there is a movement to stop Modi from flourishing because a strong India challenges the world order. “It’s not a massive conspiracy theory,” says investor Karl Mehta. “It’s just an old colonial mindset, a Western worldview.”

For all the talk of India’s authoritarian backsliding, millions of its diaspora are returning and many are heading for Bengaluru. Prospects in the US and parts of Europe, where taxes and crime rates are far higher than in India, are bleak for young people. But more significantly, the country’s economy is booming: it was recently named the world’s fastest-growing by the executive director of the International Monetary Fund, Krishnamurthy Subramanian. India’s gdp grew by 7 per cent last year and is predicted to grow by 7.6 per cent in 2024. By comparison, most economies in Europe were stagnant or even contracted in 2023. Many Indians who left the country now see more opportunities in their homeland.

Heena Randhawa, who has spent most of her life abroad and is married to an Englishman, left London when her husband got a job in Bengaluru. Though she was a marketing and communications specialist in the UK, she decided to set up an apparel company designing costumes for children. “There are many people who want to come back to India,” she says. “There are so many opportunities and it’s easy to get things done. Opening a business, especially in the creative space, would have been harder in London. It’s so easy to source quality material here. There’s a whole street in Bengaluru full of ribbons and another full of buttons.”

Bengaluru is becoming almost as well known for its micro-breweries – there are about 80 – as it is for its start-ups. monocle visited two of them and couldn’t find anyone who wasn’t planning to vote for the bjp. The closest things to dissenting voices that we encountered were endorsements with caveats. “I’ll vote for Modi because there’s no other choice,” says 22-year-old software engineer Arnav Mahajan. “We have to settle for the least bad candidate,” says his friend Anjali Sharma. The lack of a strong opposition is a common complaint, including within the Congress party, but even the most anti-bjp activists believe that the party’s victory is a foregone conclusion. The question is how big a mandate Modi will receive and what he will do with it. For those in Bengaluru, India’s city of the future, his stewardship has brought rapid technological and economic advancement.

On the city’s streets, among both rich and poor, there is a sense that this is India’s time – a sentiment that comes across more as joie de vivre than chest-thumping nationalism. The real test for the country’s strongman leader is not the election but how much discomfort the booming economy’s developmental problems will continue to cause. If he can find a way to harness the energy surging through this vast nation while preventing conflict between its religious groups or with its neighbours, India will almost certainly assume its place at the top table of nations within this century. If he cannot, its young population will surely turn away from the bjp. There’s a phrase that Indians use to sum up the country’s bumps and contradictions: “We’re like this only.” “As much as I’d love smooth roads, this is India,” says returnee Randhawa. “And I like its twists and turns.” —