Business: Manila / Global

Hold my beer

How did the CEO of a brand best known for its pilsner become the architect of the Philippines’ infrastructure revolution?

For frequent flyers travelling in and out of the Philippines, September can’t come soon enough. That’s when the state-owned operator of Ninoy Aquino International Airport (naia), Metro Manila’s chronically congested main gateway, hands over the keys to a consortium led by the San Miguel Group.

The publicly listed conglomerate has taken on the challenge of fixing naia and expectations are sky-high. The public-private partnership even got a mention in president Ferdinand Marcos Jr’s July state-of-the-nation address. “Once considered among the world’s worst and most stressful airports, [naia] will soon be a world-class international hub that we can be proud of,” he said. Is the president correct? “Yeah, 100 per cent. I have no doubt that we can turn around the airport,” says Ramon Ang, San Miguel’s ceo and largest shareholder. “Within a year you will not see any runway or terminal congestion,” he adds, before committing to notable improvements by Christmas – peak travel time for a majority Catholic country with millions of overseas workers.

San Miguel might sound like an unlikely saviour. The beer brand is principally known outside the Philippines for its eponymous pilsner, which dates back to the company’s formation in 1890 during the Spanish colonial period. But much has changed under Ang’s stewardship. A series of acquisitions over the past 15 years have transformed what was predominantly a food and beverage company with an annual turnover of €3.7bn into a €24bn-a-year juggernaut with interests in power generation, oil refinement, water, banking, roads, railways, seaports and cement. “Whatever business we do, our purpose is to make money for the shareholders and develop the country,” says Ang, explaining the logic behind his diversification strategy.

monocle visits Ang at San Miguel’s headquarters in Mandaluyong, one of the 17 cities that make up the Metro Manila region. The understated captain of industry, a child of Chinese immigrants, arrives at the office most days behind the wheel of a Toyota Camry or Land Cruiser. A car enthusiast and mechanical engineering graduate, he began his career importing Japanese vehicles before joining San Miguel in his forties and becoming one of the Philippines’ richest tycoons.

Ang’s approach has been to buy small existing businesses and grow them into industry leaders. San Miguel’s infrastructure division began 15 years ago with the acquisition of a tollway company and is now the biggest operator in the country. It opened a series of elevated “skyways” in recent years, drawing traffic away from local roads and decongesting the sole expressway linking the capital’s north and south. A two-hour journey in heavy traffic can now take 30 minutes and a few crosstown friendships have been reconnected in the process.

Ang’s enthusiasm for building roads, however, has attracted criticism for tethering Metro Manila’s future to four wheels. But as with the San Miguel-owned oil refinery Petron, which is gradually moving away from fossil fuels, the green transition has to be incremental, realistic and government-assisted. “Cars are the main transportation in Asia,” says Ang. “Our problem is we are adding hundreds of thousands of cars a year without phasing out the old ones.”

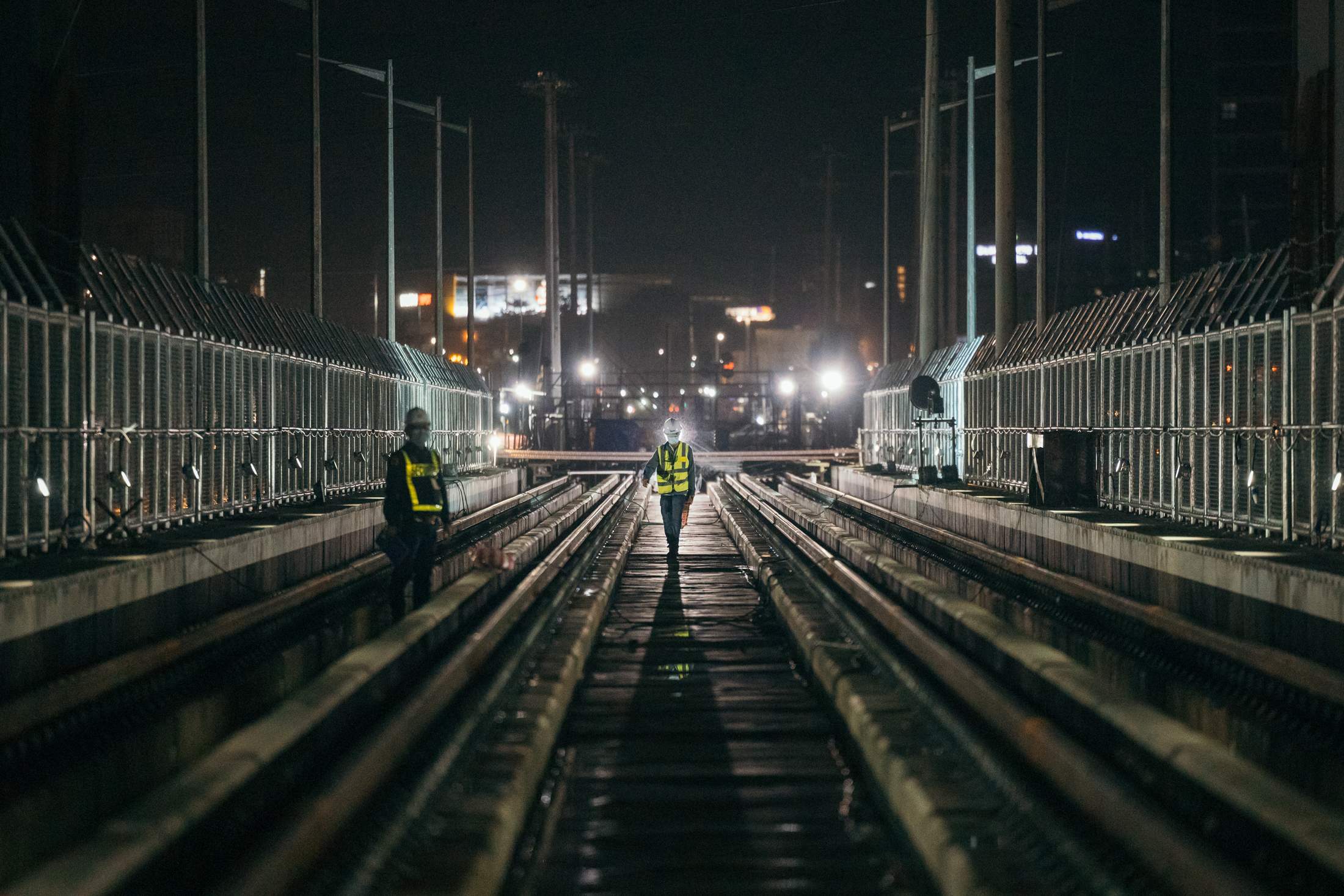

Rail is the one mode of transport where San Miguel has almost had to start from scratch. The company is building a 14-station rail line that, once operational at the end of 2025, will carry up to 850,000 passengers a day between the Bulacan province and Quezon City, Metro Manila’s largest municipality. The first major mass-transit project this century, mrt 7 will allow commuters to switch to two other lines at an interchange station – a national first. A north-south commuter railway and a subway funded by the Japanese government will soon follow, as part of what President Marcos labelled a “railway renaissance”.

“San Miguel has a lot of projects that help the development of the Philippines,” says Janno Quinto, project manager at station six in Quezon City, where construction is almost complete. Quinto, who is dressed in an obligatory high-vis vest and hard hat, recently joined from a rival toll-road company to work on elevated structures. The 29-year-old engineer stands on an empty, unfinished platform, pointing out the electrified third rail – another first. “Transportation is the way to our development,” he says.

A seasonal typhoon has just passed by Metro Manila, cancelling flights and causing flooding. San Miguel has been dredging rivers to facilitate drainage and Ang shares his opinion on what structural improvements are required to weather future storms – both natural and manmade. The patriotic Filipino is fully invested in the country’s disaster resilience and the decisive leadership he demonstrated during the coronavirus pandemic – distributing food, medical assistance and other aid – even led to calls for him to run for president in 2022. “If I become a famous politician for six years, what’s the good of that?” he says, dismissing the idea. “I will have divested all of my shares in my company and made thousands of enemies.”

rsa, as he is known to colleagues, can achieve more by sticking to what he’s good at. What’s his best deal to date? naia, he says, without hesitation. “We’ve been given the opportunity to improve the main gateway to the Philippines,” adds Ang, who turned 70 this year. It’s a surprising choice given that the commercial terms have been pilloried in the business pages for, oddly enough, being overly generous. A consortium in which San Miguel owns a stake won the naia public tender in 2022 with a bid that will earn the government $20bn (€18.5bn) and a 60 per cent cut of profits. Characteristically confident, Ang believes that he can’t lose. After all, what’s good for the Philippines is ultimately good for San Miguel.

Re-engineering naia is part of a slate of major infrastructure projects that Ang wants to see completed over the next three to five years before handing the San Miguel reins over to his eldest son, John Paul. Building an entirely new airport to serve the capital is unquestionably the jewel in his crown and the $7bn (€6.5bn) investment will almost certainly define Ang’s legacy.

The New Manila International Airport, as it is currently known, is in Bulacan, a province immediately north of Metro Manila. Site preparation was completed this year and construction will soon get under way. Once up and running, three or four years from now, Bulacan will become Metro Manila’s equivalent to Incheon in Seoul or Narita in Tokyo, while naia will be a Gimpo or Haneda. “There is no compromise in our new airport. It will be ideal,” says Ang, while scoring all of Asia’s major airports, from an engineering rather than tourism perspective. “Four parallel runways with 2km separation, good for 100 to 200 million passengers a year and a 30-minute drive or train journey to anywhere in Metro Manila.”

It’s a case of better late than never. During the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, when most developed Asian capitals were building a second airport, consecutive administrations in the Philippines dithered. Southeast Asia’s fourth-largest economy is now 30 years behind many of its peers and the aviation industry’s shortcomings are emblematic of a broader infrastructure deficit.

Closing this gap has been a flagship policy of the past three presidents. In any democracy, though, forming policy is one thing and implementing it is quite another. Ang first pitched his new airport to president Benigno Aquino iii in 2012. Aquino’s successor, Rodrigo Duterte, finally approved it in 2018. The straight-talking ceo has little to gain, though, from picking sides or apportioning blame. All governments are basically the same from his perspective and he must work with whoever occupies the Malacañang Palace – the Filipino White House.

Is Ang betting his company on aviation? The new airport must attract about 36.5 million passengers to break even, he says, while naia will reach almost 50 million this year. “There is a risk but we have to take it,” he adds, revealing the missed opportunities that motivate him more than any fear of failure. By his own count, he has walked away from five potential investments that have “cost” the company a whopping $100bn (€92.7bn) – and Ang countless hours of sleep. “My greatest mistake is not to be more aggressive,” he says. “You win some, you lose some.”

Towards the end of the decade, once San Miguel’s airports, toll roads and railway projects are complete, its visionary ceo envisages vehicular traffic and investment dollars beginning to flow from the national capital, home to most of the economic activity, to the north of the Philippines’ largest island, Luzon, where land is cheap. Traffic in Metro Manila will ease, seasonal flooding will be less severe and the country will be better placed to attract Thailand’s tourism numbers and compete for the foreign direct investment typically funnelled into Vietnam.

Metro Manila’s reputation for violence will be the last remaining sticking point – no amount of concrete can cover up international headlines about kidnappings, drug wars and extrajudicial killings. This bad publicity will have to change, Ang says, if the Philippines is going to attract the likes of Samsung and Taiwan Semiconductor. His passionate monologue has the makings of a future stump speech delivered to a crowd of potential voters. President Ang in 2028? “Politics is not me,” he says, definitively. “I’m happy now that I’m able to prepare San Miguel’s succession plan, see the company continue to do well and be able to help the community. Mission accomplished.” —

Two wheels or four?

Motorcycle ownership in Metro Manila has quadrupled in the past decade. But with congestion set to improve, it will be interesting to see the direction of two-wheel travel.