Business: UK / Global

Reaching for the sky

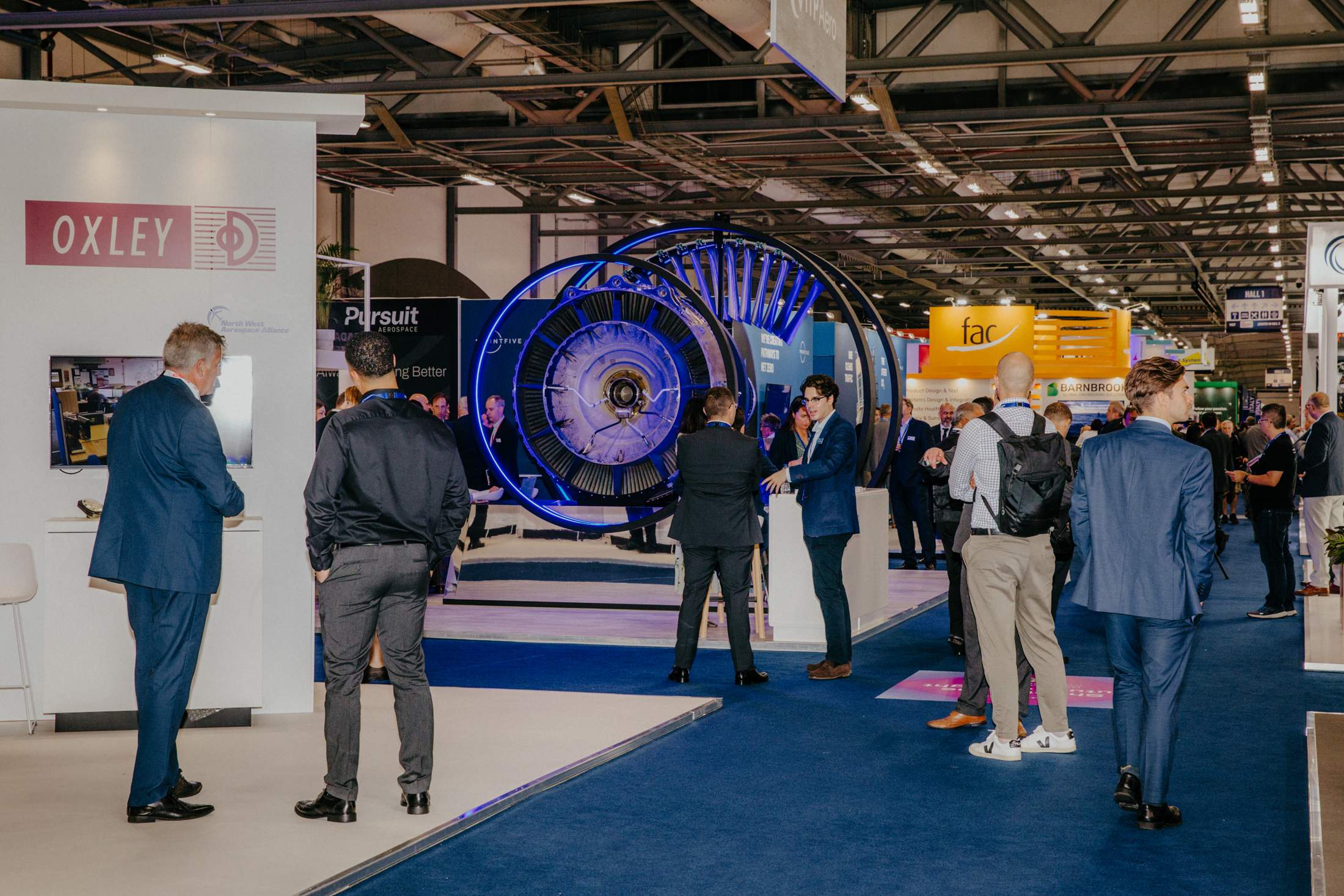

Among the simulators, stalls and aerial displays of the Farnborough Air Show, the talk is of aviation’s cleaner, quieter future.

About three minutes ago, monocle took off from downtown Brisbane. There’s an empty seat to our left and two more behind us. The cabin is suspended beneath the wings of a pilotless electric aircraft, whose silver propellers hum away. “Wave if you feel woozy,” says a disembodied voice. But airsickness won’t be a problem, not least because we’re sitting in a chair on an airfield in Hampshire, England, wearing a VR headset. The voice belongs to an employee of Wisk, the California-based Boeing subsidiary that built the pilotless air-taxi model in the middle of the tent.

It’s quite a ride. The air taxi would offer a quick, scenic alternative to a tedious 30-minute car journey. And, if all goes according to plan, it might be a transfer option for visitors to the 2032 Brisbane Olympics. But will people be willing to fly in a vehicle without a human being at the controls? “It’s like a driverless car,” says Wisk’s Carrie Bennett, who has clearly encountered this reservation before. “It’s fascinating at first but then you forget about it because everything just works. And you don’t have to worry about a child chasing a ball across the street.”

The Farnborough Air Show is huge. It has more than 500 exhibitors and some 35,000 people visit over its five days. This year’s iteration is quite quiet in terms of big orders for commercial jets, though that’s possibly a reflection of an industry still searching for its level in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. At the last Farnborough before the virus struck, in 2018, a record 1,464 orders were placed with the two biggest manufacturers, Airbus and Boeing. In 2022, that figure was 441. This year, it’s 256. Manufacturers are also beset by supply-chain difficulties, which are off-putting for potential buyers. Airbus has an order backlog of 8,585 aircraft; at current rates of production, that represents more than a 10-year wait. (Nevertheless, it’s demonstrating the a321xlr, an extra-long-haul variant of its single-aisle workhorse, which Iberia hopes to start flying this year.)

Among those making purchases, Qatar Airways has made a particular effort, to the extent that the entrance to Farnborough’s main exhibition hall resembles one of its tonier Business Class lounges, complete with a string duet and a Diptyque scent dispensary (the airline has confirmed an extension of its Boeing 777-9 order from 40 to 60). A physical presence is, however, no guarantee of sales. Brazilian manufacturer Embraer has parked on Farnborough’s aprons a handsome black and turquoise e190f cargo jet but has announced no new commercial deals (Embraer has, however, sold six a-29 Super Tucano attack aircraft to Paraguay’s air force).

If there’s one thing that demonstrates just how far the Farnborough Air Show has come since it was first staged in 1948, it is its focus on clean and renewable energy. Representatives of the aviation industry seem determined to stress that the environment has no stauncher allies. Suspend your cynicism, however, and you’ll see that there’s a lot going on in this realm. The hoardings of ZeroAvia boast of the UK-US firm’s inclusion on lists of top green-technology companies. Rudolf Coertze, its head of research and development, explains that the firm is working towards having its zero-emission hydrogen-electric powertrains adapted to small passenger aircraft the size of a Cessna Caravan or a Dornier 228. And he says that it won’t stop there. “There is no reason why this wouldn’t ultimately work with a Boeing 737 or Airbus a320 – and that could be coming by 2035. It would remove a large fraction of emissions caused by aircraft.”

Small aircraft will serve as pioneers in this regard. The Cassio is French start-up Voltaero’s rear-propeller electric- hybrid aircraft. There are high hopes for the plane and Global Sky has reserved 15 of them during the show (232 were pre-ordered before the end of Farnborough). Jean Botti, Voltaero’s ceo and a former chief technical officer at Airbus, is an enthusiastic salesman. He sits us in the pilots’ seats and explains how the airframe can be adapted to carry passengers, post or cargo, or perform rescue operations. Future, larger models will have retractable undercarriages and pressurised cabins. “It could replace a lot of light aircraft and also compete with business aviation,” Botti tells monocle. “There’s a lot of criticism of private jets and, of course, this is much, much cleaner. It will also be cheap to fly: €400 to €500 per hour.”

Europa XS monoplane

For all the talk of a cleaner, quieter future for aviation, some aspects are eternal. The most sophisticated machines will still need the most basic parts, someone will always be needed to build them and a marketplace as busy as the Farnborough Air Show will always help to sell them. Beagle Aircraft is based nearby in Dorset; customers for its components include bae and Leonardo. Among the exhibits at its Farnborough stall are a cargo door from a business jet, an outer leading edge from the wing of a German Air Force Tornado and a flight simulator. “We didn’t make that,” says Beagle’s order-book manager, Tom Rosser. “But if you don’t have something to draw people in, they’ll walk by. And for the five or so minutes when they’re on the simulator, you have a captive audience. That lets us explain why the things that we make are important.”

Coming to Farnborough, says Prosser, isn’t just an exercise in PR outreach. A lot of meaningful business gets done here. “For a company our size – just 100 to 120 people – it wouldn’t be worth doing as a loss leader,” he says. “Last year we paid for the stand with the sales that we made on the first day. And the lunches definitely help to get agreements over the line.” —

flying taxis

Up in the air

Global

In The Jetsons, flying cars glide effortlessly around Orbit City (writes Jakob Funkenstein). But since the cartoon was first broadcast in 1962, the basic airframe and engine designs of large and small commercial aeroplanes haven’t changed very much. However, a new generation of electric vertical takeoff and landing (evtol) light aircraft will soon enter the market, promising to revolutionise urban transportation. evtol makers, prospective operators and vertiport companies claim that these vehicles will end traffic gridlock and shorten commutes – and your ride will be fully autonomous. Though it’s unlikely that we will be riding in private evtols 10 or 20 years from now, we might see ride-sharing in high-density locations, such as airports, sports venues and tourist attractions.

A huge effort is now under way to figure out the infrastructure needs of evtol operations in big cities. Traffic and avoiding collisions with other aircraft are key concerns. Vertiport construction also represents a major investment – the more landing pads, the better. However, that requires space, which is costly. All of the investment required in design certification and infrastructure development begs the question: will the end product be affordable to ordinary users? Every player appears to have a different solution for making urban air transport economically viable. Manufacturers such as Joby and Archer are so confident that not only are they producing evtols, they are planning to operate them too.

How the fare of an evtol ride is calculated will depend on factors including distance and demand but operators will probably have to charge many times more than the current land-based taxi firms. There’ll be technology enthusiasts who will jump at the chance to be one of the first to try out this next-generation commute but there’s no guarantee that even they will remain loyal evtol users.

If you build it, will they come? In Paris, a protest movement called Taxis volants Non merci is already opposing the idea. Safety concerns aside, the movement argues that it’s not worth paying social costs such as extra noise, let alone the desecration of Paris’s skyline. So it might be decades before average citizens can hail an air-taxi. —

Funkenstein teaches aviation management at IU Internationale Hochschule in Berlin.

Top three deals at Farnborough

Flynas

The biggest deal at this year’s event was between Airbus and Riyadh-based Flynas, Saudi Arabia’s first low-cost airline. Flynas is best known as the airline of choice for budget-conscious pilgrims visiting Mecca: during the last Hajj season, the airline filled 100,000 seats. It is now significantly expanding its all-Airbus fleet, ordering 130 a320s and 30 a330s, with delivery to begin in 2027 – a huge move by an airline whose current fleet consists of just 64 aircraft.

Japan Airlines

This year, Japan Airlines (jal) finalised orders for 20 Airbus a350-900s and 11 a321neos, and for 10 Boeing 787-9s, with an option on 10 further 787s. The a350 order was reduced by one from the terms announced in March: the 21st had been intended as a replacement for the jal a350 lost in a runway collision at Tokyo Haneda in January but jal has decided that it can live without it. Boeing was clearly grateful for the 787 order: the firm’s senior vice-president, Brad McMullen, went out of his way to thank jal for sticking with the company.

Korean Air

Boeing’s recent difficulties were reflected by a restrained presence at Farnborough. The much delayed 777-9, for example, was only represented by a mock-up of its cabin. So, Boeing will have appreciated the vote of confidence from Korean Air, which signed for 20 777-9s, 20 787-10s and options on another 10 787-10s – a reported outlay of $12.6bn (€11.5bn). Due for delivery in 2028, these will be a significant boost to Korean Air’s fleet ahead of the completion of its long-planned acquisition of Asiana Airlines.

Automatic for the people

Though autonomous aircraft will initially be small, there are companies now insisting that there’s no practical reason why airliners can’t be programmed to fly as reliably as any drone.