Expo / Global

A piece of England in Malta

Malta’s pre-eminent architect Richard England isn’t slowing down just yet. The prolific octogenarian writes poetry, draws cityscapes and is currently penning a book based on biblical characters. Over his six-decade career, he has created a captivating body of colourful, dreamy, postmodern delights. Along the way, England has reimagined religious spaces, challenged the island’s prevailing styles and breathed life into cities the world over. Monocle heads to Malta to meet the maestro and find out more about his career, ideas and inspiration

“Some of my favourite music is by Eleni Karaindrou,” says Richard England, hitting play on an album by the Greek composer. The octogenarian architect is welcoming monocle into his home in St Julian’s, a small enclave on the east coast of Malta. “My grandmother introduced me to the music of Enrico Caruso as a child and it stuck. I now have a collection of 12,000 records. My family says that I suffer from a condition called ‘tenoritis’.”

England is one of Malta’s most influential designers. His accolades include 11 International Academy of Architecture (iaa) Awards and the iaa Grand Prix; he was also made a Maltese Officer of the Order of Merit for his work. While we’re here to talk architecture, it’s clear that this visit will be about more than just bricks and mortar. Glasses of whisky are poured and a spread of hobz biz-zejt (a Maltese entrée of crusty bread topped with tomatoes and olive oil) is laid out, as England describes the creative endeavours that he is currently pursuing. “If I rest, I rust,” he says.

There’s his daily ritual of drawing cityscapes and landscapes (“Despite computers, the bridge between mind and paper is still best crossed by the hand”), and work to be done on a book featuring the biblical figures of Cain and Judas (“I wrote one on Lazarus, who must be the most frustrating guy in the Bible – he spends four days in the afterlife, then comes back and tells us nothing”). There are poems too and, of course, architecture – he has just completed a striking meditation garden and chapel in the Maltese town of Santa Venera for Christian organisation Dar il-Hanin Samaritan. There are similarities across his creative practices. “Both writing a poem and making architecture are about building,” he says. “With poetry, it’s using sound and silence, and with architecture, it’s using solid and void. They have the same aim: to uplift the spirit.”

Born in Sliema to an architect father, England graduated from the University of Malta’s architecture school in 1960, before continuing his studies at the Politecnico di Milano. While there, he worked as a student architect in the studio of mid-century master Gio Ponti. “I was very lucky because with Ponti, you would be at the drawing board and he would come and spend 45 minutes with you, discussing whether a detail should be this way or that,” says England. Other famous architects would also come through the studio door: Scarpa, Nervi, Neutra, Gardella, Albini.

England returned to Malta in 1962 with a glowing letter of recommendation from Ponti. It was then that his father, Edwin England Sant Fournier, who was one of Malta’s best-known designers at the time, gave his son a first commission: a new church in the hamlet of Manikata. “At the age of 23, I started designing it,” says England of the project, which ultimately took 12 years to complete. “At first, the villagers didn’t like the design because they wanted a dome that was bigger than the neighbouring village’s.” They soon came around to England’s vision, which was inspired by Malta’s megalithic temples and girna, the circular stonewalled storage structures found in the island’s agricultural fields.

Finished in earthy tones and furnished with a bespoke altar, lectern and chairs, the parish church was hailed as a masterpiece of modern regionalism upon its completion in 1974. “The archbishop didn’t like it, especially the wall made from rubble and field stones behind the altar,” says England, laughing. “I told him that I would plaster it but didn’t, hoping that, at 88 years old, he would forget. When he visited the church a few weeks later, he quietly grabbed my arm and said, ‘I see that it’s difficult finding a plasterer in Malta.’”

The church – and its break from the island’s baroque religious architecture – put England on the map but he was keen to evolve his practice. “My first period of architecture was about regionalism, which was of its time but also of its place. I was practising what William Blake said: you become what you behold. It was almost instinctual but such an approach needed an intellectual overlay.” This came in the form of the creatives who arrived in Malta in the 1960s, with whom England collaborated. There was architect Basil Spence of new Coventry Cathedral fame and abstract painter Victor Pasmore, along with zoologist and surrealist Desmond Morris.

In addition, the architect began winning overseas commissions and requests. He was invited by Baghdad’s city architect, Rifat Chadirji, alongside others such as Robert Venturi and Ricardo Bofill, to help develop a new vision for the city in the early 1980s. There were character-building experiences associated with the project, which matched England’s rise to prominence. Flights were routinely rerouted to Oman, which would result in a 21-hour bus ride to the Iraqi capital, crammed in the vehicle with chickens and goats. On one occasion, England was dragged from a taxi when security services spotted him taking a snap of the Baghdad Conference Centre. Held at gunpoint, he was interrogated and left in a jail cell overnight before earning his release by exposing the film and thereby destroying the photos. There were similar run-ins in Saudi Arabia and Kazakhstan (in the latter’s capital, Astana, an aide to the mayor, reminded England to be careful when disagreeing with the city’s leader, since he had been an Olympic wrestling medallist).

Such experiences helped England to develop an appreciation for the character of a place. It’s an ethos embedded in the architect’s now-signature style – one that has become a benchmark for Maltese architecture. “Vitruvius said that architecture is about firmness, commodity and delight – or venustas in Latin,” says England. “Firmness and commodity relate to construction but while many people translate venustas to mean ‘beauty’ or ‘delight’, for me, it refers to atmosphere. It is felt by all senses – oral, aromatic, somatic and possibly also gustatory.”

By the 1980s, England was creating unique atmospheres using surreal compositions of volumes and planar surfaces made from exposed Maltese stone and reinforced concrete. These also included pastel-coloured surfaces, punctuated by arched, rectangular and square openings.

Examples of the style, which are still standing, include private gardens and residences such as 1982’s Garden for Myriam (dedicated to his wife) and Villa G in Siggiewi. His public buildings include the mirage-like Aquasun Lido hotel pool built in 1983 and the Spazju Kreattiv, a cultural centre that opened at the turn of the millennium. Places of worship feature prominently in his portfolio too, including the Church of St Francis of Assisi in Bugibba and several projects for Dar il-Hanin Samaritan.

When England is quizzed on his legacy, he is carefully optimistic. “It’s not for me to judge but, hopefully, future generations will look at projects such as these as something that beautifies the island, that moves the spirit and elevates the soul.”

Judging by the numerous homeowners who opened the doors of their residences and the priests who ushered monocle in through their parish entrances at England’s request, it seems that this appreciation is already firmly established on the island. Even though many England-designed buildings have been knocked down or altered beyond recognition, there are thankfully those that are still standing, despite being something of a labour of love to maintain. “My architectural philosophy might well be defined in the words of Tennessee Williams – ‘I don’t want reality, I want magic,’” says England, reflecting on his portfolio. “Another of my favourite quotations is, ‘Those who dance are always thought insane by those who don’t hear the music.’”

Rest assured that, should you visit and experience some of England’s works, you’ll feel the magic and hear these metaphorical melodies. And if you’re lucky enough to visit them with England himself, he might even play you one of his favourite tenors too.

Richard England’s selected Maltese portfolio

Parish Church of St Joseph

Manikata, 1974

A modern masterpiece, inspired by Malta’s mix of ancient and agricultural landscape.

Garden for Myriam

St Julian’s, 1982

Abstract forms, reminiscent of surreal paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, define this garden.

Aquasun Lido

Paceville, 1983

Freestanding walls and follies surround this hotel pool, creating a mirage-like effect.

Church of St Francis of Assisi

Bugibba, 1993

A large geometric form rises out of the earth towards the heavens.

Villa G

Siggiewi, 1994

A private commission.“We changed the position of two doors and then built the house.”

Spazju Kreattiv

Valletta, 2000

England transformed the Knights’ Period property into a spectacular cultural venue.

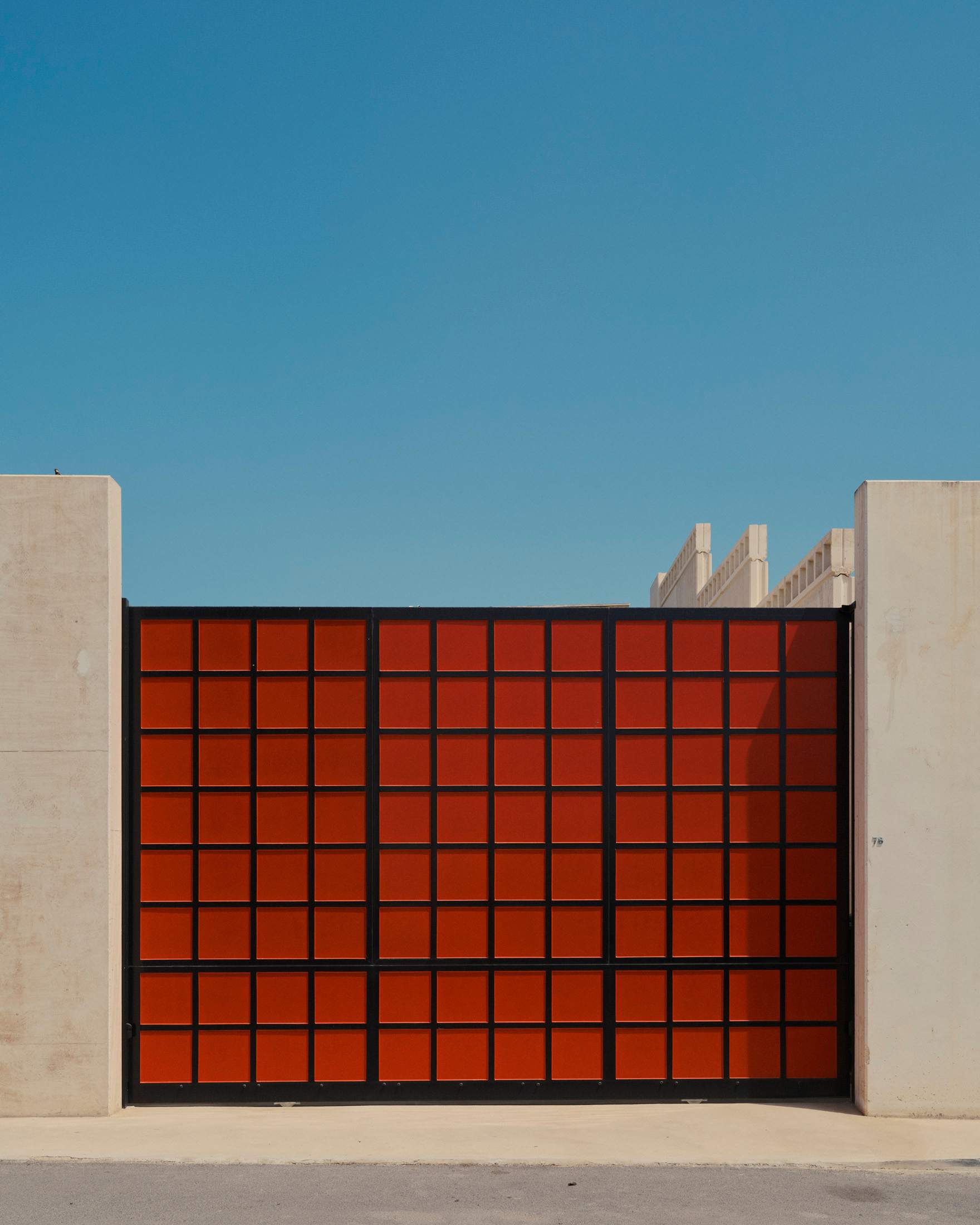

Dar il-Hanin Samaritan

Santa Venera, 2014-present

A series of projects has been completed for this religious organisation, including gardens and chapels with sculptural elements that play with light and shadow. New additions include a landscape completed with glass artworks by the architect’s son, Marc England.