Affairs: National dress / Global

Why national dress is back in fashion

Pride, joy and the power of tradition are coalescing to make young people across the globe take delight in traditional styles.

The Great Male Renunciation is a term used to describe a phenomenon in the late 18th century whereby European men all began to dress the same. Out went almost any form of ostentation (wigs, gold braids or high heels) and in came the dull lounge suit. Since then, the Western way has been hegemonic. Indeed, at the end of the 20th century the suit and its female counterpart, the ball gown, had become the comportment of choice for almost any formal setting anywhere in the world. It appeared as though Western-led globalisation had succeeded in not only homogenising the world of trade but that of dress too.

Twenty or so years later, the foundations of this bland new world look shaky. As was the case in the late 1700s, such phenomena are difficult to identify at the time (the term “Great Male Renunciation” was coined in the 1930s) but it seems that in many countries there has been a re-embracing of national dress. Some may ascribe this trend to the dark forces of nationalism but it’s worth noting that it has also coincided with the retreat of another shoddy Western invention: cultural appropriation. At about the same time as the grand panjandrums of globalisation were smugly surveying their spoils, a subset of people in Western academia were, like po-faced Gok Wans, decreeing what was and wasn’t acceptable to wear.

National dress became smothered by the censorious: a dead thing meant for museums rather than real life. The joy and generosity involved in the mutual exchange of cultures were now fraught with guilt. Of course, there have been times in the past when people have donned national dress in order to ridicule and belittle others, but this too, thankfully, has for the most part been consigned to the bin. Today, people from all corners of the globe see the wearing of another’s national dress as an act underpinned by admiration. It is in this spirit that the following feature has been put together. From Nigeria to Malaysia, via Bavaria, Ukraine and the Arabian Gulf, we look at how national dress is making a comeback for a variety of reasons: political, economic and, yes, sartorial. We have also included an illustrated chart such as readers might remember from classroom walls of yore – made with love for eyes that wish to learn and appreciate, not roll. —

1.

desert dress

Thawb and abaya

The Gulf

To the untrained eye, the garments worn by men across the Gulf region might seem indiscernible: a white ankle-length dress paired with a headscarf in either white or a red-and-white checkered pattern. But each of the seven states in the region has its own distinctive male robe, known as a kandora, thawb or dishdasha, and headscarf, known as a ghutra or shmagh.

The Gulf states (especially Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the uae) have undergone an astounding transformation over the past half-century. The uae, for example, was only established in 1971 and moved from being a country dependent on farming, fishing and pearl-diving into one of the most technologically advanced and richest urban societies in the world. Here and in other Gulf states, traditional attire has acted as an anchor to the past, tempering the lightning-quick changes happening elsewhere in society.

So, what are the differences between men’s dress in the Gulf? In the uae and Oman, men wear a collarless kandora with a tarboosh or farakah, long tassels roughly analogous to a Western tie. The Emirati tarboosha extends from the neck to the belly button, while in Oman, it hangs just below the collarbone. In the uae, men either tie their headscarf around the head like a turban (known as the hamdaniyah or essama) or wear it in the formal style with the agal, the black crown common across the Gulf. In Oman, the formal headgear is a turban called the massar, while a kumma, a cap without a visor, is a less formal option. The Kuwaiti, Saudi, Qatari and Bahraini dishdasha or thawb, which all feature a collar, are almost identical. The Saudi one is more of a tight fit with a two-button collar and shirt sleeves designed to accommodate cufflinks, while the Kuwaiti thawb has a one-button collar and wide sleeves without cufflinks. The Bahraini and Qatari thawbs are looser, with pockets on the right chest and softer collars.

These garments evolved over centuries to suit nomadic lifestyles: white fabrics helped their wearer survive the region’s heat, while the ghutra or sifrah (a wrap worn around the head) protected against dust and sunlight. The agal was once used to secure a camel’s legs at night and worn on the head when not in use. Though the vast majority of the region’s people now live in air-conditioned cities, these garments still serve a utilitarian purpose while providing and enforcing a common identity. The Gulf’s leaders and public figures have played a crucial role in the latter regard. By choosing to exclusively wear thawbs and ghutras at public events, they signal their intention to preserve these cultural traditions. Indeed, traditional dress is compulsory for many who work in government-run institutions in Saudi Arabia, Oman and Qatar.

Young Emiratis, many of whom are more likely to wear Western dress on a casual basis, often come to cherish the time they spend in the thawb or abaya (its female equivalent) at work. Saaed AlMheiri, a business development manager in Dubai, believes it reinforces an intergenerational bond that’s important as young Emiratis are exposed to Western mores. “It reflects where I come from and the upbringing that shaped me,” he says. “Traditional clothing perfectly balances timeless elegance and a deep connection to values passed down through generations. It seamlessly blends into both business and casual settings, making it a symbol of continuity and solidarity.”

2.

united in style

Batik and kebaya

Malaysia

During coronavirus lockdowns in 2020, Malaysian dressmaker Nellie Song began sewing clothes for her daughter. She decided to experiment with batik, a colourful textile with wax-resistant dye patterns that originated in Java and has become a staple of Malaysian traditional wear. Song’s daughter received so many questions from friends about her mother’s designs that the duo decided to start their own tailoring business, Batik by Nell. “It all started with the kebaya,” says Song. The kebaya is a traditional garment worn by women, an intricately detailed blouse accompanied by a wraparound sarong.

In a country as multicultural as Malaysia, with large Malay, Chinese and Indian populations as well as numerous smaller ethnic groups and indigenous tribes, there is no single national dress – there are dozens. At the National Textile Museum in Kuala Lumpur, a line of mannequins, each sporting a different traditional outfit, stretches across the room – a Chinese silk jacket here, a headdress made of tree bark there. Amid such diversity, the kebaya is a rare cross-cultural garment. “Women of all ethnicities and social classes in Malaysia, from royal families to commoners, have worn the kebaya. It holds a special place in Malaysian culture,” says Tengku Intan Rahimah binti Tengku Mat Saman, the director of the National Textile Museum. “The kebaya has evolved to reflect Malaysia’s unique cultural identity, incorporating elements of Chinese, Indian and Malay cultures.”

It has also become a border-crossing, soft-power wielding sartorial ambassador. Pre-colonial and colonial migrations of different populations across the Southeast Asian archipelago brought the kebaya along for the ride. In 2023, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore and Brunei jointly nominated the kebaya for Unesco’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, an admirable show of regional unity in a part of the world that loves to bicker about whose version of a certain noodle dish is the most authentic.

Soon after she launched Batik by Nell, Song was rushing to fulfil orders for modern spins on batik and classic sarong kebaya and even the occasional batik tie or pocket square. She has designed custom versions of various traditional garb – a batik Chinese cheongsam, batik Indian bridal wear and Malay-style batik sets for Ramadan celebrations. Many customers are young Malaysians like Song’s daughter, Wong Ann Jee, and her friends. “We’re so used to the Western idea of dressing but I feel that, as we grow older, people start to be more open and receptive towards wearing local textiles,” says Wong, who is 27. Some Batik by Nell customers are Malaysians living abroad who want traditional outfits to wear to weddings and parties in the UK and Australia. “People are just getting more comfortable with representing their culture.” Wong often wore sarong kebaya when she had to deliver presentations at university. “That’s one of the nice things about Southeast Asian traditional wear: it’s considered formal attire now,” she adds. “I was so sick of wearing boring corporate clothes and a button-up shirt!”

3.

pride of place

Vyshyvanka

Ukraine

Gathering with friends to celebrate her 26th birthday in Kyiv, Ada Wordsworth chose to wear the Ukrainian national dress, known as a vyshyvanka. It was a hot August evening in 2024 and the venue a shady, wild beach on the banks of the Dnipro River. Packing a picnic and bottles of prosecco, Wordsworth donned her outfit for the evening: a linen vyshyvanka dress embroidered with sheaves of wheat and chestnut leaves, symbols of Ukraine’s capital.

Wordsworth came to the country in March 2022, abandoning a master’s in Slavonic studies at Oxford University to set up a charity, Kharpp, which helps to repair buildings damaged by war, in the northeast Kharkiv region. She was immediately drawn to the vyshyvanka. “In the early months of the full-scale invasion, everyone was wearing the dress all the time and I started to, too,” says Wordsworth. “I’ve been travelling around the country and love buying vyshyvankas in different regions. Each has a different use of colour, patterns and embroidery; you can tell where it has come from just by looking at it.”

Though British and a relative newcomer to the country, Wordsworth has tapped into a feeling that many Ukrainians have had since the country gained independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. In 2017, designers Natalia Kamenska and Maria Gavryluk founded Gunia, a Kyiv-based fashion and homeware brand that has become a go-to for stylish, modern takes on the vyshyvanka. “Our journey began in the Ivan Honchar Museum, Ukraine’s national centre of folk culture,” says Gavryluk. “We started working in their archives in preparation for launching Gunia, and it sparked journeys across the country, visiting different collections and libraries.” Gavryluk describes a yearning common across a nation whose heritage was violently suppressed under Russian rule. “In school, we were taught about Ukrainian folk tradition in a very limited and uninspiring way,” she says. “Walking into that museum, I realised how varied my country’s culture really is.” Strolling down Kyiv’s trendiest streets, many passers-by can now be seen in Gunia’s designs, with symbols and details taken from visits to workshops and villages across the country. It is a far cry from the Soviet era, when people were jailed for wearing their vyshyvanka in public.

But it is Kamenska’s work as a stylist to Ukraine’s first lady, Olena Zelenska, that has helped show off the vyshyvanka on the international stage. “Cultural diplomacy through fashion is extremely important, especially in Ukraine’s current situation,” says Kamenska. “The clothes signal national belonging. They convey who we are, showing Ukraine’s importance and history to the world.” Representing her country on foreign visits, Zelenska is often greeted by émigrés of Ukrainian descent wearing vyshyvankas. The first lady is regularly seen in one chosen by Kamenska from Gunia’s collection, or one of the many brands now offering contemporary takes. “Because of the modernity of the pieces, they can also reflect the wearer’s personality – they mirror an otherwise hidden individuality,” says Kamenska.

Back on the Kyiv beach, the light is softening as Wordsworth’s guests arrive at the party. Many have taken the host’s cue in opting for a vyshyvanka. “Coming from a left-wing London background, I was aware of cultural appropriation,” says Wordsworth. “At first, I was nervous about wearing the vyshyvanka. But I’ve found that Ukrainians appreciate foreigners wearing it. It shows our admiration for a country and a culture that has been suppressed for so long.”

4.

team player

Lederhosen and dirndl

Bavaria, Germany

When Max Lechner was 15 years old, he decided he wanted to work with leather. The material had played a central role in his upbringing on a farm in Hofolding, 20km outside Munich. On special occasions or while out hunting with his father, Lechner had always worn lederhosen, the traditional leather pants of the Eastern Alps. So, he applied for a job with a Säckler, the craftsmen who had historically processed leather into bags and trousers. There, Lechner found his calling. He loved the mix of conviviality and comfort that lederhosen signify, while at the same time envisaging a renewed boom in the garment.

The first wave of lederhosen arrived in the 19th century, when the Bavarian royal family, the House of Wittelsbach, began to wear the garment in official portraiture. “When Bavaria became a kingdom in 1806, its rulers looked for local traditions to unite their diverse subjects,” says Simone Egger, a cultural anthropologist at Saarland University. “So, they set up Oktoberfest as Munich’s annual funfair. They also promoted leather pants, initially worn only by Alpine hunters and farmers.” The annual Oktoberfest in Munich occasionally featured a Trachtenumzug, a parade of traditional costumes. Since 1948, the event has run annually with about 9,000 participants, 250,000 spectators and one million viewers on live TV watching men and women in lederhosen and dirndl, the corresponding dress for women.

Today, lederhosen are promoted by the new kings in town: the players of Bayern Munich football club. This tradition began in 1979, after rival fans had taken to chanting, “Take the lederhosen off Bayern.” As a cheeky riposte, the Bayern players started appearing at their away games clad in the traditional attire. They began wearing lederhosen at trophy celebrations, team outings to Oktoberfest and when presenting new players at the club. “The message is attractive for anyone yearning for belonging,” says Egger. “Put on lederhosen and you become part of the team.”

Team building was on the Bavarian king Ludwig II’s mind when he supported the foundation of the first Trachtenverein, a club to promote regional costume, in 1883. Today there are about 900 such clubs with 180,000 members in Bavaria. “These members are like ambassadors who wear their lederhosen most days,” says Lechner. He is a member of his local Trachtenverein Brunnthal and owns four different lederhosen: one for work, two for festive occasions and a longer one for winter. Their durability is one reason why people are willing to pay €2,500 for a pair of Lederhosen Lechner’s handmade trousers. While it is possible to get cheap factory-made equivalents for €100, these are usually produced from chemically tanned goat leather in Sri Lanka, India or Pakistan. Lechner’s trousers, on the other hand, are made using European deer leather that is tanned in Bavaria in fish oil for months. “The most labour-intensive part is hand-stitching the embroideries with local motifs,” he says.

While regional pride has always defined lederhosen, the garment’s political message has changed significantly over time. When Bavaria lost its king after the First World War, lederhosen became a reactionary symbol of protest against the newly formed liberal Weimar Republic. The open-hearted revival of local costume started only after the Second World War. It was epitomised by the hostesses for Munich’s 1972 Summer Olympics, dressed in dirndl to welcome the world to Bavaria.

5.

higher purpose

Agbada, buba and aso-oke

Nigeria

On a continent where Western powers have historically dictated everything from diet to dress, Nigeria has managed to maintain a strong individuality. “Nigeria is so comfortable in itself and its identity,” says Obida Obioha, a Lagos-based creative director and founder of Obida, a brand making clothes inspired by traditional designs. In fact, the country, Africa’s most populous, has been arguably the most successful on the continent at exporting its culture: from Nollywood movies to musicians Burna Boy and Fela Kuti.

But one art form that hasn’t yet been celebrated is fashion. While agbada suits and bubas used to be ubiquitous on the streets of Lagos and among the Nigerian diaspora, only recently have people begun to turn back to these garments. “In the 1980s and 1990s, people wanted to dress like in the West, wearing Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger,” says Obioha. There was this idea that if it’s from abroad, it’s nicer. Or at least, that used to be the case. “My generation is changing that.”

It was during the pandemic that designers and local brands began working with techniques and materials found on home soil. “Importing and exporting was slow, so we had no choice,” says Rukky Ladoja, founder of Dye Lab, a brand that makes hand-dyed garments. The textile du jour is aso-oke, a native cotton that was historically spun into elaborate outfits worn for events such as weddings. “The meaning of aso-oke is ‘higher clothing’,” says Ladoja. “It’s the king of clothing, designed for special occasions.” Though there’s never been a scarcity of aso-oke, the fact that it was reserved for parties or ceremonies meant items became less prominent, quickly losing relevance with younger generations. “Our parents would treasure aso-oke; it was something they inherited from their parents and became collector’s items,” says Seun Oduyale, a fashion entrepreneur and image consultant, whose family runs Bisbod Aso-Oke, which specialises in this native fabric.

Then, around 2020, more designers started incorporating aso-oke into everyday clothing, using a strip on a pocket or a lapel to add a flash of Nigerian colour. They also tweaked and contemporised the shapes of bubas and agbada suits, making them more casual and wearable. “Labels have looked to traditional attire and methods of making fashion and inserted their own spin on them,” says Obioha. Roomier cuts and cotton fabrics suit life in Lagos, especially during the summer when temperatures regularly hit 40c and the air is like a wet sponge. “We already wear loose garments,” says Ladoja. “The agbada is 100 per cent cotton, so it’s breathable. The style and shape are loose; you feel comfortable.”

They also feed into Nigerians’ love for boldness in personality and dress. “Aso-oke tells a story. People want to emote with their clothing,” says Oduyale. “We’ve gone from saving clothes for special days to looking good every day.” Wearing the printed bubas and agbadas is also a signal that you’re part of a crowd that’s in the know about emerging designers. Not only are many of these labels worn by Afrobeat stars but they carry a certain cachet. “Africa is rising and the spotlight is on us, from the music to food to art,” says Oduyale. “We are presenting our culture to the world as an enticing, marketable product and the world is loving it.”

National dress differs across the globe depending on region, ethnicity, climate and more – but every nation has a story to tell through its traditional dress. It remains an important cultural tool, used to create a sense of belonging.

1.

Botswana

The most common fabric used in national dress in this southern African nation is leteise, a dyed cotton with geometric patterns. Women and men often wear a blanket of animal skin called a kaross.

2.

India

Traditional dress in India varies by region and climate and are part of daily life for many. The clothing – whether a saree for women or the dhoti garment for men – can be traced back thousands of years.

3.

Bolivia

Bolivia’s Andean dress, worn by indigenous Aymara populations, was developed in the 16th century and includes ponchos for men and pollera skirts for women. The bombín (bowler hat) came via British railway workers and was clearly a hit.

4.

Mongolia

The deal with Mongolia is the deel, a kaftan-like garment accompanied by a sash, belt, hat and boots. Every ethnic group has its own style and there are 400 different types of hat.

5.

Argentina

There’s a focus on the mythical figure of the gaucho, a Southern Cone cowboy, and the paisana rural figure, both of whom gained prominence in the fight for independence from Spain. Also add in ponchos and bombacha trousers.

6.

Fiji

The national dress for men and women here has been a kilt-like skirt known as a sulu since colonial times. The first examples were brought by missionaries from Tonga and originally signified a conversion to Christianity.

7.

Finland

Based on everyday outfits from the late 17th and early 18th century. There was a revival in national dress from the 19th century but it wasn’t until 1979 that the National Costume Council of Finland was created.

8.

Japan

Now mostly worn for formal occasions, the kimono (literally “things to wear”) became the principal means of dress from the 16th century. It’s worn left side over the right and secured with a sash called an obi.

9.

Mexico

Regions and ethnic groups affect the styles but a dominant form belongs to the charro, the Mexican horseman whose uniform worn at equestrian shows includes a wide hat, boots and an embroidered jacket.

10.

Thailand

Known as chud thai, Thai traditional dress was given impetus by Queen Sirikit in 1960 when she started to establish national costume for Thai ladies (there are eight types of dress).

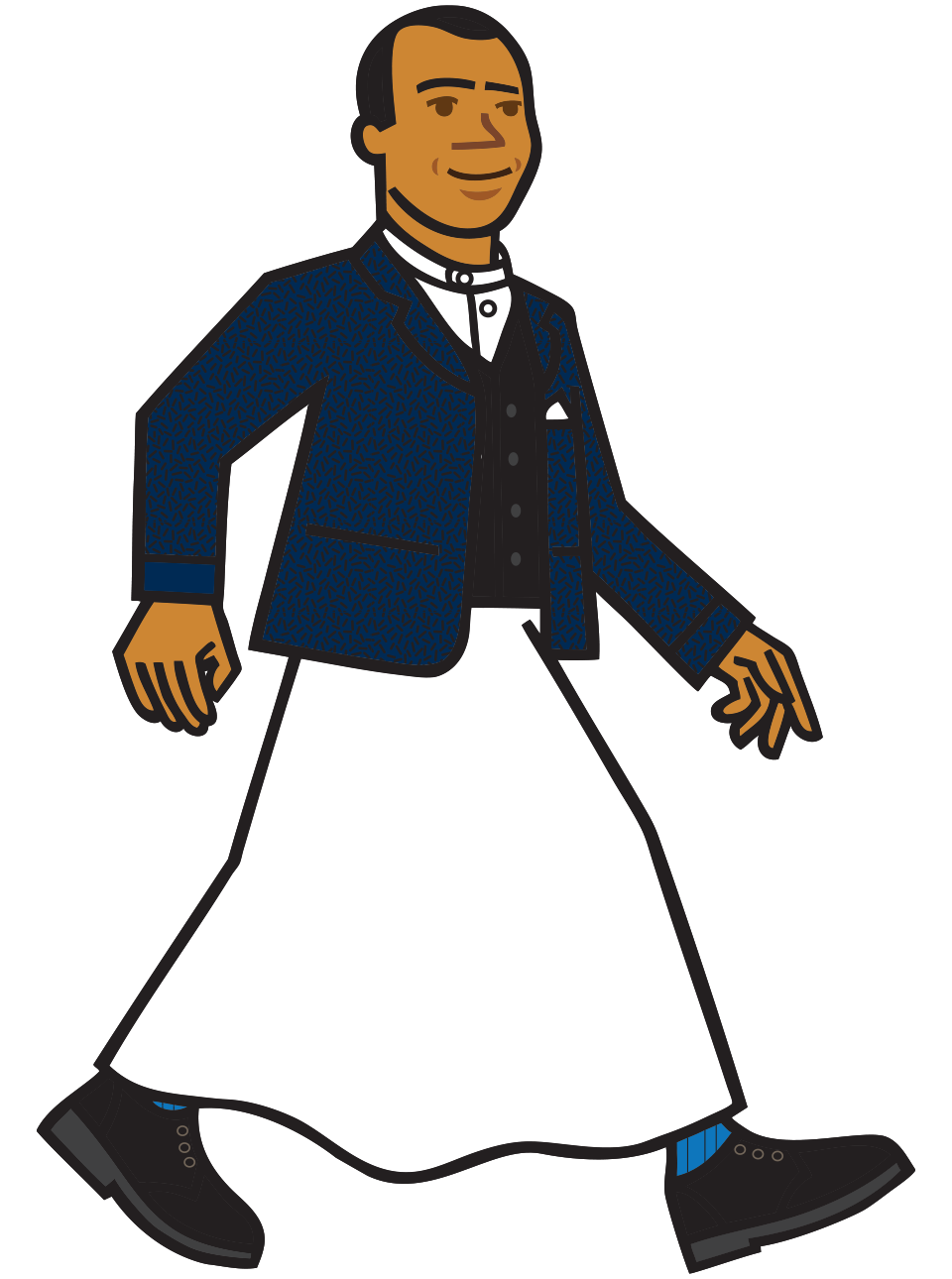

11.

Uganda

Women’s colourful gomesi dress is said to have been developed as a high-school uniform in the first half of the 20th century, while men’s kanzu consists of a long, white tunic and jacket, first worn by Arab traders.

12.

Morocco

Both sexes wear flowing garments, with men donning a hooded djellaba and women a kaftan. The design of kaftans varies depending on origin, with every area using different embroideries and jewellery. The male fez is thought to have Ottoman origins.