Affairs: Urbanism / Johannesburg

Can Africa’s richest city function again?

South Africa’s largest city is shrugging off its crises and stubbornly moving forward.

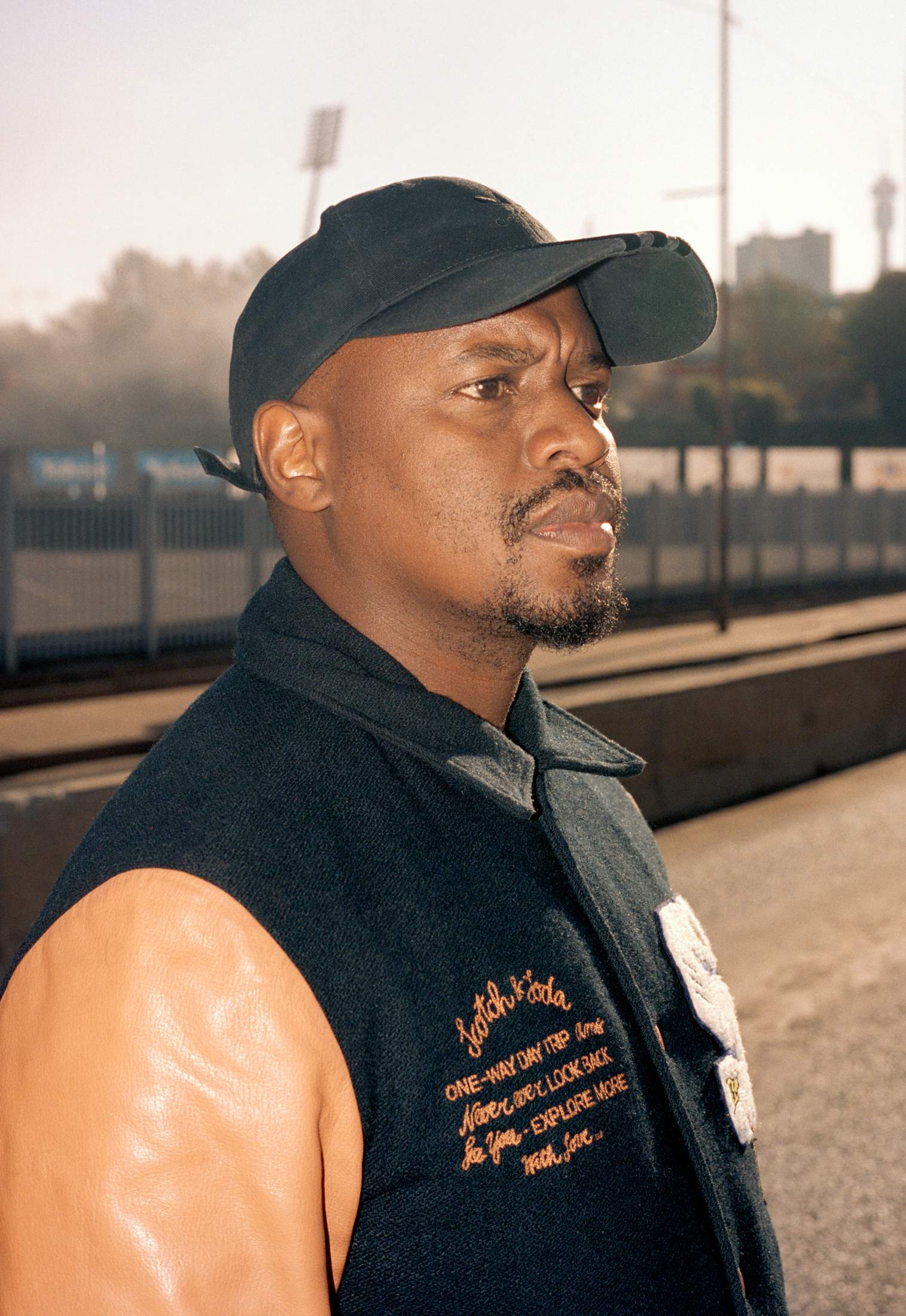

Melusi Mhlungu has no time for speculating about whether or not his hometown can be saved. “If Joburg dies, the country dies,” he tells monocle at the foot of Ponte Tower, a 54-storey concrete skyscraper on the edge of downtown Johannesburg that was Africa’s tallest apartment building. Two years ago, Mhlungu was in Brooklyn making Super Bowl half-time commercials, living the high life as a New York ad man. Today he’s back home – and he has a new job: selling a city whose “brand” is bathtub-sized potholes and rolling blackouts.

The project that brought the 36-year-old advertising director back was unexpected. On a trip home two years ago, he got a call to meet Robert Brozin, a local businessman turned philanthropist and co-founder of fast-food chain Nando’s. Brozin had an intriguing pitch for Mhlungu: Nando’s was getting involved with a project to revitalise Joburg’s historic inner city, much of which has fallen into disrepair since big businesses retreated to the suburbs in the 1980s and 1990s. The work was centred around a complex of neoclassical buildings recently vacated by mining giant Anglo-American. They were slated to become, among other things, a satellite campus for a local university. But Brozin’s ambitions went beyond that. He described to Mhlungu a grand plan: beautifying inner-city streets, improving security, training entrepreneurs and creating jobs and housing for the homeless. “There’s no point in just handing out sandwiches,” Brozin told monocle. Instead, the businessman wanted Joburg residents to reimagine their city – and he wanted Mhlungu to be the one to make the pitch to them.

“It was a weird offer,” says Mhlungu. After all, he would be trying to sell a place steeped in dysfunction, whose official tagline, “a world-class African city”, had become an ironic punchline. South Africa’s largest (and Africa’s richest) city has always had a reputation for grittiness, which is perhaps a euphemistic way of saying a high crime-rate. Indeed, there were 2,600 carjackings in Gauteng, the province comprising Joburg and its environs, between April and June of this year, and the city ranks among the top 50 globally for its homicide rate (though it comes in below Baltimore, Detroit and Cape Town). But in the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic, Joburg’s woes were multiplying, as its politics imploded and several long-brewing infrastructural crises spilled over simultaneously. The city’s ageing power grid, for instance, was on its knees. From 2022 to mid-2024, rolling blackouts left most of Joburg in darkness for five to 10 hours a day. In the city where 70 per cent of South Africa’s businesses are headquartered, factories began cutting production. Thieves sliced through now-dead electric fences and public hospitals cancelled hundreds of procedures because operating theatres were too cold. Water outages became a regular occurrence for at least half of the city. In July 2023 a rotting gas pipe exploded beneath a downtown street at rush hour, snapping open the road above. The next month, a squatter-occupied building burst into flames, killing 77 people.

Meanwhile, the engine of South Africa’s economy was effectively leaderless. Between 2021 and 2023, the unstable ruling coalition cycled through eight different mayors. “Since everyone realised that you might be in office for just two weeks, any long-term planning is out the window,” one city official, who asks not to be named, tells monocle. Indeed, in July of this year, the city council projected it needed $12bn (€10.8bn) just to catch up on maintenance for its road, power and water infrastructure. But before it could begin to act on that figure, mayor number eight since 2021, Kabelo Gwamanda, resigned and the musical chairs began all over again. Given all of this, Brozin’s offer was more than a request to market Joburg as a nice place to live. He was asking Mhlungu, in essence, to give its five million residents an answer to an existential question: could the city even be saved? And, if so, what would it take?

There was something compelling in the project for Mhlungu. Joburg is South Africa’s melting pot and its gateway. Between 2011 and 2022, almost five million people migrated to Gauteng from other parts of the country. The province is also home to nearly half of South Africa’s immigrant population. Mhlungu loved living in the US but also missed his hometown, a place crackling with the ambition of an entire continent. If any deeply broken place could turn itself around, he knew that it would be Joburg, where people had always improvised around the city’s failings. When Joburg’s streetlights went out, beggars became traffic cops to guide cars through the intersection. After road accidents, private security companies redirected traffic and passing doctors pulled over to care for the injured until the ambulances arrived. “Like it or not, there’s a strong creative energy in places that don’t quite work,” says Mhlungu. So he agreed to Brozin’s offer and in 2023 returned home.

If Johannesburg is an ambitious place, though, right now that go-getter attitude doesn’t extend to its leadership. For three decades after the end of apartheid, the city was ruled by the African National Congress (anc). The liberation movement turned political party has dominated South African politics for the past 30 years. It saw Joburg through a period of whiplash transformation between apartheid city and democratic metropolis. But in 2016 the anc lost the Joburg local government election. Since then, no single party has achieved a majority on the city council. This has left it in the hands of increasingly unstable coalitions and prompted an ongoing game of mayoral seat swapping. Gwamanda was still in power when monocle began reporting this story in June and anc old-timer Dada Morero occupied the seat when we finished in September (both were unavailable for interview).

National elections in May did little to steady the ship. Countrywide, the anc’s share of the vote dipped below 50 per cent for the first time in South Africa’s democratic history, forcing the party into a ruling coalition with its closest rival, the Democratic Alliance. In Joburg, meanwhile, the anc governs in coalition with a different set of smaller parties. The churn at the top has made it difficult for city leaders to plan or execute long-term projects. “The budget is made, the budget is reversed, the budget is taken away,” says Dan Moalahi.

Moalahi is one of about 20,000 people who live in Slovo Park, an area in the south of Johannesburg that urbanists refer to as an “informal settlement”. That means its creation wasn’t authorised by the state, though the term is usually shorthand for neighbourhoods made up of shacks. In 2019 one in five of Johannesburg’s five million residents lived in such a settlement. Despite their name, many are not transient places. Slovo Park has existed for 30 years, far longer than many of the city’s sought-after suburban housing developments. It has wide, gridded roads. The properties lining them are neatly divided by fences and trees. Even the shacks themselves feel rooted. Moalahi’s has glass windows, plywood kitchen cupboards, a washing machine and goldfish swirling in a tank by the TV.

Before Johannesburg fell into its governance crisis, many communities in the city were already finding creative ways to take on jobs that the city wouldn’t do for them. Slovo Park exemplifies this stubborn self-sufficiency. The neighbourhood was founded in the early 1990s by workers in the nearby factories seeking a cheap, convenient place to live. Since then the city has tried to evict Slovo Park’s residents on several occasions to no avail. For more than 20 years the area has been run by a group of democratically elected “community forums”, who organise security patrols and hold conflict-mediation sessions. They also provide social services including food aid, shelter for victims of domestic violence and services for addicts. More impressive are their guerilla-style infrastructural upgrades. In 2010 the community forum got fed up with endlessly petitioning the city for running water. So it pooled money from residents to buy pipes and then hired plumbers living in the neighbourhood to connect the existing communal taps at the end of each block to individual properties. “We invited Joburg Water [the municipal provider] to come see,” says Moalahi. “We are doing the upgrading you can’t do.”

The private sector has long had a hand in plugging the government’s gaps too. Joburg overflows with private security companies, private ambulances and private electricity grids, the latter a major factor in ending the rolling blackouts of the past two years. You can now use an app to report potholes to a local insurance company, which dispatches teams to patch them up. Every day, eight vans emblazoned with the words Pothole Patrol leave a nondescript office park in the east of Johannesburg. Over the past three years, they’ve filled about 250,000 potholes.

“We are heroes to people,” says the group’s vehicle manager, Joshua Baile, as he nudges his van onto a roundabout. Pothole Patrol is run by Discovery, South Africa’s largest insurance provider, which has obvious skin in the road-repair game. “Filling potholes pays for itself,” says Kgodiso Mokonyane, Discovery’s head of strategy and value-added products. In the first year of the project, she says, pothole claims by Discovery customers in Johannesburg fell by a quarter, even as they increased by 45 per cent in the rest of Gauteng, the province of which the city is a part. There’s a clear shortcoming to letting an insurance company fix city roads, of course: they get to decide which ones matter and which don’t. By and large, Pothole Patrol doesn’t fix roads in Joburg’s many historically black, working-class neighbourhoods. Then again, there are no shortage of potholes in the shopping-mall and office-block-lined roads of the suburbs either.

During monocle’s visit, Baile pulls his van to a stop at the intersection of two busy roads in a part of town cluttered with new-build housing estates. He and his team cordon off the pothole, a watermelon-sized dent, and get to work. First they sear the surface of the road around the hole until it is hot enough that the top layer of asphalt can be scraped off. Then they shove that loose pavement into the hole, topping up the area with some fresh asphalt. Finally, they heat it again to set it in place. Within minutes, cars are gliding over the smooth road as though the hole never existed.

Mhlungu and Brozin aren’t the only people trying to rebrand Johannesburg. On a Thursday evening, monocle joins Sanza Sandile, a self-taught chef who runs a popular supper club from a second-storey shopfront on Rockey Street, the main drag of the inner-city neighbourhood of Yeoville. Most days, Sandile serves a 10-course dinner of Afro-fusion dishes. Tonight the menu includes a Ghanaian-inspired gumbo, a saffron-tinged rice dish described as a “jollof-paella hybrid” and a beetroot salad. The meals that Sandile prepares are designed to reflect the diversity of the city on display outside the supper club’s windows. “Joburg is a tough city but it’s also amazing,” he says. The chef grew up in the dying years of apartheid, in the black township of Soweto. The place had a certain cultural – and culinary – uniformity that reflected just how effectively apartheid had kept different communities of South Africans apart.

By contrast, when Sandile first came to the inner city in the mid-1990s, shortly after Nelson Mandela became president, the area seemed like a dress rehearsal for the county’s future. Interracial couples held hands in the streets, brushing past white suburban skaters and Congolese sapeurs in brightly coloured designer suits. There were gay clubs and strip clubs, cafés with names like Café Pigalle and wine bars where returning political exiles engaged in debates about governance and democracy. But Sandile was most struck by one particular element of this melting pot. For him, sampling new cuisines was an act of rebellion against the country’s historical separations, “a way to kick the doors in”. He started selling food from a stall before moving upstairs seven years ago. Visitors have included Anthony Bourdain and Dave Chappelle, and even now, he says, the bookings come in faster than he can keep up with, proof that the city’s demise has been exaggerated. “This is still the big city of hope,” he says. “It’s home to the brightest and best from all over our continent.”

For inner-city activist Shereza Sibanda, Joburg’s saving grace is its residents’ unwillingness to settle. Whether it’s people piping their own water or insurance companies plugging potholes, she says that “people know that they deserve better than what they have”. That has been true, she claims, for her whole life. It was true when her father migrated here from Mozambique in the 1950s to work in the city’s gold mines. It was true in 1976, when she joined the uprising of schoolchildren in Soweto that marked the beginning of the end of apartheid.

And it’s on display now too, in the Joburg residents who pour into the downtown legal aid clinic that Sibanda helps to run, asking for help fighting illegal evictions or exposing crooked cops. She is amazed sometimes at how little Joburg’s recent struggles have done to dull its appeal as a city where anyone can shrug off their history and start over. “People keep coming to Joburg,” she says. “They won’t stop”. In recent years, about 300,000 people have migrated to the city’s province every year. It isn’t as though Joburg’s troubles don’t affect them. Poor leadership from their government has left its citizens – literally – in the dark. But their reasons for believing in the city transcend rolling blackouts and burst water pipes.

Take Sethokwane Zungu, a 31-year-old who lives in a one-room metal shack beside a paper factory. Since he moved here from a rural village a decade ago, Joburg has been, to say the least, difficult. Last year, unable to afford rent, he found himself squatting in a five-storey downtown building with no running water or electricity. One night in August, it caught fire. Of the 400 people inside, 77 died. Zungu lost the supplies for his small baking business and his entire life savings – about €100. “I have really lost hope,” he tells monocle. We ask if he has considered leaving the city. “Never,” he replies, shaking his head. “It’s still Joburg. So maybe things can turn around.” It’s a sentiment that we’ve heard over and over again. “There’s nothing to love about Joburg but people do anyway,” as Brozin puts it. The project he helped to dream up, Jozi My Jozi, has been slowly ramping up since Mhlungu was hired last year. When monocle visited, the initiative was cleaning up a dozen scruffy highway off-ramps leading to the inner city. “This isn’t about creating another Singapore,” says Mhlungu. In Joburg, the grit is part of the charm. But Jozi My Jozi wanted to give people reasons to feel proud of their city again. “The brand is broken,” adds Mhlungu. “But the people are not.”

Joburg in numbers

4.8 million

Population of the City of Johannesburg.

15 million

Population of Gauteng province, which includes Johannesburg.

0

Navigable bodies of water running through Johannesburg – one of the world’s largest cities not built in proximity to a river or ocean.

79

Percentage of the world’s gold that came from Johannesburg and its environs in 1970, at the height of South Africa’s gold mining boom.

11

Official languages in South Africa, all of which are spoken in Johannesburg.

3,400

Beds at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, in Soweto, the largest hospital in Africa and one of the 10 largest in the world.