Affairs: Aviation / Global

As geopolitical tensions rise, how free is the sky?

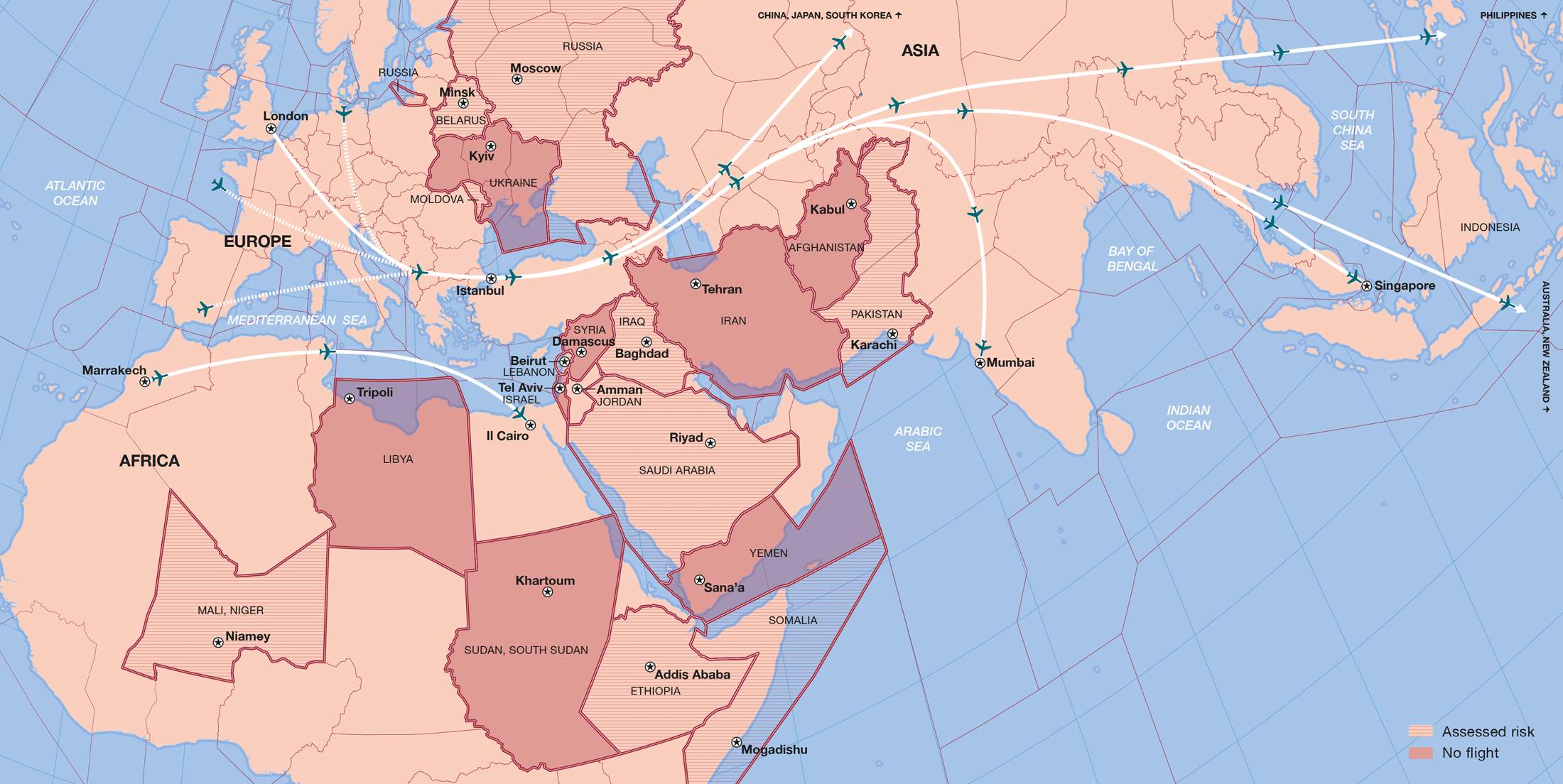

Conflicts in the Middle East, Europe and beyond have reshaped the world’s airspace, making much of it off-limits. We find out how airlines are negotiating the new faultlines on the aeronautical chart.

In his book Skyfaring, Belgian-American writer and pilot Mark Vanhoenacker notes that while aviation is “commonly associated with the levelling of difference, with the bulldozing of borders between places and times and languages”, it has also “resulted in the creation of new realms of geography”. The “administrative divisions of airspace” are not the traditional global demarcations that we might recognise. Rather, writes Vanhoenacker, they are “sky countries” – regions governed by air-traffic-control authorities, with borders and histories of their own, even ranging beyond terrestrial boundaries into “oceanic airspace”.

Charting the new no-fly zones

Japan, for instance, is known to pilots as “Fukuoka”, while the zone dubbed “Salt Lake City” actually covers parts of nine US states. The country with the largest airspace in the world, Australia, is not the nation with the largest landmass (which is Russia). This is because Airservices Australia oversees air-traffic control not only for the sovereign nation but the “flight-information regions” of the Solomon Islands and Nauru, a vast swath of territory comprising about 11 per cent of the world’s total airspace.

While the sky might symbolise freedom, there’s little about it that’s free in a monetary or legal sense. Piloting through a country’s airspace means incurring overflight fees. Travelling above “flyover country” in the US, for example, will set you back $61.75 (€57) for every 100 nautical miles. Fees are typically charged to pay for the provision of air-traffic control. The steep cost of crossing the Trans-Siberian route, however, has been used to subsidise Aeroflot, Russia’s flag carrier.

Most airlines have paid these fees for the convenience of reducing travel times and distance – as well as saving fuel costs. In 2021, US carriers petitioned the State Department to help them to expand their ability to fly through Russian airspace, warning that without this, “US airlines will be forced to operate on alternate, inefficient routes, resulting in time penalties, technical stops, excess co2 emissions and loss of historic slot rights.”

Not long afterwards, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. When the EU, US and Canada blocked all Russian aircraft from their borders, Moscow retaliated in kind, banning any flights over its territory. The “sky countries” were brought crashing down by events on the ground.

One of the companies most directly affected was Finnair, which had staked a big slate of its business on Finland’s proximity, via Russia, to Asia. One Saturday evening in late February 2022, Päivyt Tallqvist, the company’s senior vice-president of communications, heard that the EU was planning to close its airspace to Russian planes. “We knew that Russia would retaliate,” she tells monocle. Finnair immediately cancelled flights that were due to depart the following day. “We didn’t want to be in a situation where we would send customers, crew and aircraft to an airspace that might close at any moment.”

The airline’s route-planning and operations teams set to work on getting its Asian service back up and running, with Tokyo and Seoul as its first priorities. The Russian disruption was so huge that planners could no longer rely on software alone. Finnair scrambled to dust off a route that was a stalwart during the Cold War. The polar transverse, with fuelling stops in places such as Anchorage, was common when the skies over the Soviet Union were largely off limits to Western aircraft (save for direct flights to Moscow). Finnair was a pioneer in this respect; in 1983 it began offering the first non-stop flights from Europe to Tokyo, with special planes carrying extra fuel tanks.

In the late 1980s, in the wake of glasnost, the ussr started reopening its skies and the polar route became less common. But now that it was essential again, planning was required, says Finnair’s vice-president of network management, Perttu Jolma. Diversionary airports in northern Japan or Canada had to be examined, for instance, to ensure that they could accommodate an Airbus a350. Planes’ extended-range twin-engine operational performance standards (etops) were tweaked to boost the time that they could fly on one engine, allowing them to reach airports that were further away. Polar survival kits had to be added to aircraft.

But the polar route doesn’t always make the most sense. Given the favourable tailwinds running west to east, says Jolma, Finnair also takes a southern route, more or less equidistant to the polar route, to destinations such as Tokyo. For example, Finnair ay73 from Helsinki to Narita flies due south from the Finnish capital, hooking a left near Kosice, Slovakia, skirting Ukraine, passing over the Black Sea, then beelining through Central Asia – over countries deemed safe but where conflicts are not unknown. Returning flights tend to take the polar route but nothing is guaranteed. Even space weather events, such as a burst of radiation, can influence whether a plane will fly the polar route. “It affects the aircraft equipment, which can limit how far north you fly,” says Jolma.

Finnair’s Asia flights, like those of every European airline, now take more time, burn more fuel and require more crew than in recent years. There are other ripple effects too. Previously, says Jolma, Finnair could fly from Helsinki to Tokyo and back in a day. But because of today’s longer journeys, if the plane were to turn back straight after reaching its destination, it would arrive in Helsinki at an inconvenient hour for onward connections. So it now spends more time on the ground in Japan. As a result of such constraints, a number of routes, such as Beijing and Sapporo, no longer make sense financially or logistically.

Of course, it isn’t just Finnair that has had to contend with the closure of Russian airspace. A 2024 paper in the Journal of Air Transport Management estimates that the Russian and Ukrainian airspace closures resulted in some 6 per cent of global flights being hit with a cost increase of 13 per cent. And while the Russian closure is the largest impediment to global air travel, it is by no means the only patch of sky that has been affected by geopolitics on the ground.

Russia-related closures: in figures

1. Size of Russian airspace: 17,879,000 sq km

2. Share of international air traffic to/from Russia: 5.2 per cent

3. Percentage of global air traffic stopped completely owing to conflict: 4.32 per cent

4. Average detour of redirected flights: 13.32 per cent

5. Average fare increase per minute of added travel time: $1.56 (€1.46)

Whether it’s legal to fly over an area is one question; whether it’s safe to do so is another. This was brought into tragic relief in 2014 by the downing of Malaysian Air flight 17 (mh17) over eastern Ukraine by Russian-backed separatists using a buk surface-to-air missile system. “That was the moment when a lot of operations changed,” Eric Shouten, a former Dutch intelligence officer and the ceo of security consultants Dynami, tells monocle. “mh17 opened the eyes of many countries and airlines and made them reconsider flying over a conflict zone. Before that, it was still normal to fly high and dry over it – you could look down and see the impacts but you were never the target.” The emergence of Man-Portable Air Defence Systems (Manpads) meant that even non-state actors could down civilian aircraft.

Mark Zee is a former pilot who now runs Opsgroup, a membership-based organisation for “people at the pointy end of international flight operations”, whose founding was inspired by the downing of mh17. “After that incident, it became clear that a handful of airlines had been avoiding Ukraine,” he says. “The question was, if these people knew about the risk in Ukraine, why didn’t everybody know?” The answer, he says, is that there was no easy way to share the information; nor, he says, is there a single global authority making the call on whether it is permissible or even advisable to fly in a certain airspace.

“There isn’t a clear edict to say that this is the responsibility of the icao [the International Civil Aviation Organisation], the iata [the International Air Transport Association] or a national government,” says Zee. “It’s complex and there isn’t a great precedent for it.” One country might deem another to be off-limits, while another might regularly use it to route flights.

So he set out to create a one-stop clearinghouse for information, drawing on a network of people in aviation and government, as well as official “Notams” (notice to air missions) and “sfars” (special federal aviation regulations). The group’s Conflict Zone and Risk Database is a colour-coded map of the world’s hot spots, grouped into three levels of risk. Among the countries that are currently coded red (“Do not fly”) are Sudan, where a militia shot down a foreign-registered cargo aircraft in October, and Yemen, which “remains an active conflict zone” and “should be avoided”.

The map is constantly changing, says Zee. Events such as the recent series of Iranian missile attacks on Israel and the subsequent retaliation change the state of play. “Now we’re in a very topical conversation about what airspace risk looks like. What does it mean for civilian aircraft to fly close to war zones? How far away is far enough?”

Countries whose airspace the European Union Safety Aviation Agency (EASA) currently has restrictions or advisories against flying in:

1. Mali

2. Libya

3. Pakistan

4. Somalia

5. Syria

6. Yemen

7. Israel

8. Iran

9. Lebanon

10. South Sudan

11. Sudan

12. Afghanistan

13. Ukraine

A few days before monocle visits, a couple of Lufthansa flights were “suddenly turned around because they didn’t want to go into Iranian airspace”, says Zee. “It can be a really fluid situation, in which airlines have to make on-the-spot decisions.” The US has prohibited its carriers from flying over the Tehran Flight Information Region (which covers Iran) until 31 October 2027. The European Aviation Safety Agency, meanwhile, “recommends not to operate in the airspace of Iran at all flight levels”. Germany’s authorities have put it more bluntly, declaring that there is a potential risk of “escalating conflict and anti- aviation weaponry”.

Yet a quick glance at flight-tracking website Flightradar24, which has become a real-time measure of the pulse of global aviation, will show a number of flights in the region. “A lot of those will be local traffic,” Ian Petchenick, Flightradar24’s director of communications, tells monocle. “You’ve got regional airlines such as Air Arabia and FlyDubai still transiting. Then you have the Russians, who continue to use Iranian airspace to get to places such as Abu Dhabi.” Earlier this year, Emirates was fined $1.8m (€1.7m) by the US for flying in Iranian airspace because the flights had a code share with Jetblue, an American company.

Insurance is one of the other main determinants in assessing airspace risk. Mark Shurville, an analyst at UK-based Hive Aero, an underwriter that specialises in the aviation sector, notes that such carriers might not have much of an option. “They could be facing pressure from their own governments to maintain a particular route,” he says. “Or, if they’re surrounded by challenging airspace, they simply might have no choice but to fly those routes.” These carriers, he says, “will turn to us and say, ‘We have been doing this for years. We know what we’re doing.’ But there will be others that don’t. So, part of our job is to determine which is which.”

Navigating the skies is more than just a matter of vectors and radio beacons. It also requires steering through a flurry of Notams and national advisories. Afghanistan, for example, has been off-limits to most Western carriers, as much for aerial threats as for the fear of landing at an airport with no air-traffic control and an unfriendly regime. Opsgroup compares landing in the country as “akin to ditching in oceanic airspace”.

But recently the US, among others, made a razor-thin slice in the east of the country – routes p500 and g500 – available at a lower altitude: 30,000 feet, rather than the previous 32,000 feet. They did so because “some operators were struggling to use these airways at higher levels”. Opsgroup notes that while the security situation and the safety of the airspace above has not improved since the Taliban takeover, “What has changed is the normalisation of risk.”

When traffic is diverted from these flyover zones into other airspace, it has “knock-on effects”, notes Petchenik. “Air-traffic control has to manage hundreds of extra flights through already congested airspace. There are only so many places where you can put aircraft before you have to start limiting them and say, ‘OK, we can only handle this many per hour.’” With all the closures, he says, “You’re down to two lanes on the highway.”

Petchenik spends a good portion of every day with his eyes on the Flightradar24 map – he says that he can tell where the jet stream is or what the weather is like in Scandinavia based on the movement of planes. “It’s all about pattern recognition.” What strikes him about the current map is “how big the holes are”. There was, he says, “never a tonne of traffic over Ukraine after mh17 but there was traffic”. Now it’s all gone. The constant shift of routing resembles “one of those rectangular puzzles where you have all the pieces except one and you have to keep moving them around – but the pieces never stop.”

Samantha Costas is a first officer for Envoy Air (owned by American Airlines) who has a political-science doctorate. She wrote her dissertation on the use of airspace as a foreign-policy tool. She tells monocle that there are myriad examples of how politics comes into play in the sky, from the separate air-traffic-control regimes that Turkish and Greek Cypriots employ on the island of Cyprus – meaning that pilots get competing instructions – to cases of political symbolism, such as when Cuba offered the use of its ordinarily closed airspace to the US after the September 11 attacks (the offer, she says, was ignored).

Costas looked at instances when airspace was closed – when Algeria made its skies off-limits to Morocco, for example, or the aerial sanctions against Qatar by the Arab Quartet (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the uae and Egypt) – and found that the actions were costly and didn’t lead to a change in the target’s behaviour. “This was the puzzle,” she says. “If closures don’t work, why are they still being used as a foreign-policy tool?” One answer might be how easy they are to impose. “You just send a Notam saying that your airspace is closed and it’s an immediate foreign policy.”

Climate scientists warn that global heating will make air turbulence worse in the years ahead. Geopolitical turbulence might also make journeys ever bumpier. —

For more on the fast-evolving world of aviation, see our report on Andalusia.