Hospitality revivals / Nice

Back to life

From entrepreneurs who are rediscovering Nice’s hidden charms to the trio reviving a faded hotel in the desert outside San Diego, we meet the business folk who know how hospitality, drinking and dining can nourish a neighbourhood.

01.

Nice

France

The courtyard at Hôtel du Couvent feels more like a sleepy village square in the south of France than the scene of one of the season’s most anticipated hospitality openings. Locals with market baskets queue to pick up freshly baked loaves from the boulangerie and a florist rushes past with an oversized bouquet, while chic patrons sip cups of café crème on the leafy terrace. Watching the ensemble from the shade of an orange tree is Valéry Grégo, the hotelier who spent 10 years thoughtfully converting the 400-year-old Couvent de la Visitation, a Nice landmark, into a five-star retreat.

“A decade is a long time to do as little as possible,” he says with a smile. “Ideally, I want people to think that we have been lazy all this time. That would be the best compliment.” “Lazy” is not the word that we would use to describe a €100m undertaking such as this. But Grégo, who sold his other hotels (including Paris’s Le Pigalle and Les Roches Rouges on the Côte d’Azur) to finance the venture without the help of investors, has a point. The site seems as though it has always existed in this form, with its sober, subdued décor courtesy of Parisian firm Festen Architecture and peaceful, terraced gardens designed by Tom Stuart-Smith – plus a bakery and apothecary located in the same places as during the nuns’ tenure. And yet, until recently, Hôtel du Couvent was the kind of project that would have been unthinkable in France’s fifth-largest city.

Hôtel du Couvent

Though Nice is now buzzing with new activity, this was far from the case in 2008, when incumbent mayor Christian Estrosi took office. He felt that the city, with its belle époque palaces and faded French Riviera charm, was in need of a refresh to attract a younger and more high-end crowd. And so Estrosi initiated the hotel conversion of the historic Couvent de la Visitation, calling for a competition from which he selected Grégo’s grounded take on luxury hospitality. But Estrosi was also keen to introduce more accessible urban options, which helped to bring in establishments such as Mama Shelter and the California-inspired Pam Nice to the gentrifying neighbourhood of Riquet. “We want to be a hub for quality, not mass tourism, where locals and visitors can live together in harmony,” says Rudy Salles, delegate president of the Nice Côte d’Azur metropolitan tourist office. As the city’s deputy mayor until 2020, Salles was Estrosi’s right hand in advancing this vision. For instance, in 2015, the duo opposed the construction of a cruise port to protect Nice from the same pollution and crowding issues faced by tourism hot spots such as Barcelona and Venice.

Recognising that a city must first be welcoming to its residents before it can reposition itself on the world stage, Nice invested heavily in improving its tram and bicycle network, enhancing green spaces and improving the cultural calendar. “The first ambition was to make Nice a city where people could live well,” says Salles. “If it’s pleasant for the Niçois it will be pleasant for tourists.” While the efforts are ongoing – such as the construction of a vast urban forest cutting through the centre – the city is already reaping significant rewards. Café terraces are now spilling onto once traffic-heavy squares, major venues are taking form to host events such as the 2025 United Nations Ocean Conference and new direct flights to Europe, North America and the Gulf are being added weekly.

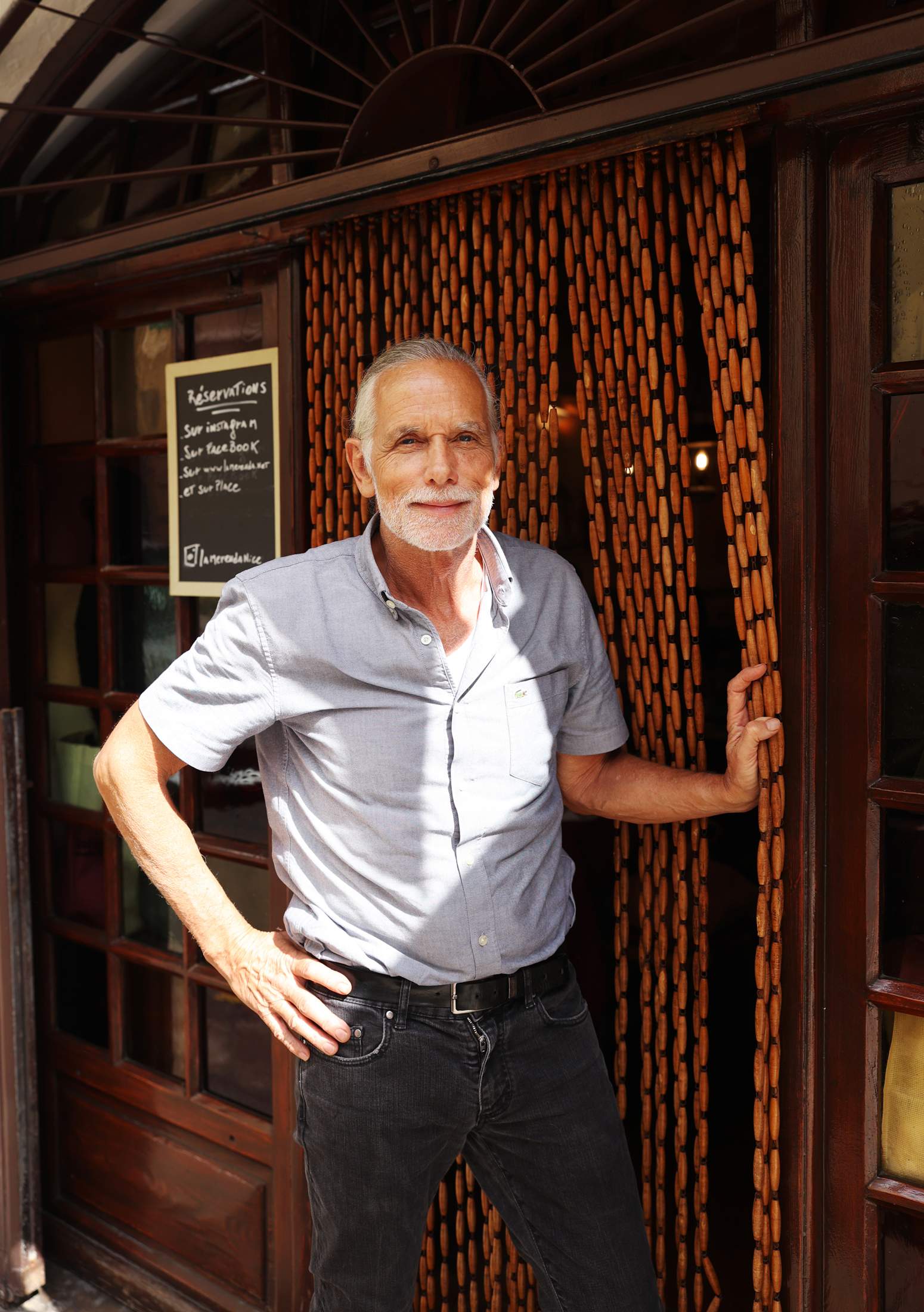

Hotel occupancy rates aside, the city’s transformation has been good for other local commerçants too. Trésors Publics, a boutique for “Made in France” goods popular with Niçois and tourists alike, has recently moved to bigger premises, expanding its shop floor by 30 per cent. The new space is also set to include a 200 sq m cellar that will host workshops with artisans. An upstairs chambre d’hôte is expected to open in 2025. Even hospitality mainstays, such as Dominique Le Stanc’s celebrated restaurant La Merenda, are adapting to the times: while it remains cash-only and still doesn’t accept phone reservations, the 25-seat establishment now offers online bookings, resulting in a full house for each of its four daily services.

Handsome businesses founded by a new generation of entrepreneurs are springing up across the town. Many of the founders are Nice born and bred; they have sought experience elsewhere only to bring their new skills and knowledge home. Among them is the former beverage manager of Experimental Cocktail Club, Maxime Potfer. His bar, Povera, opened near the old port in July. “Before, there was nothing to do in Nice after midnight,” he says from behind the bar. “For the first time, we have more demand and anticipation than supply.” The result is a welcoming business environment with space for newcomers – from neighbourhood bakery Pompon to Italian-French restaurant Marmar and coffee and ice-cream shop Frisson.

Café crème at Frisson

Frisson sells artisanal ice cream and coffee

A strong hospitality and retail industry is encouraging other professionals to set up shop here too. Emmanuelle Gillardo spent 25 years in Paris, working in PR. But she believes that now is the time to return to her native Nice. “I noticed that Parisians were being hired to handle PR for southern French hotels and restaurants,” she says. “We need local experts who can create a more authentic and relevant discourse about the city.”

In the same way, hospitality outlets are increasingly calling upon creatives from the Côte d’Azur to infuse their spaces with Mediterranean flair. The recently renovated La Pérouse hotel features antiques curated by Rémi Chiappone of the Cap d’Ail and Paris-based Galerie Astéria. While Paris is still central to their trade, many creatives are turning their backs on the capital in favour of the south. Léa Ginac recently designed a set of wooden stools, tables and marble vases for Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport but Nice, where she has just finished exhibiting at Trésors Publics’ future chambre d’hôte, is home. “I love that there’s the sea, the mountains and the proximity to Italy,” she says. “Nice is so complete. I don’t understand why it hasn’t had this kind of effervescence before.”

Hospitality

Number of hotels: 202

Number of hotel beds: 10,700

Increase in four and five-star establishments since 2020: 60 per cent

Occupancy rate: 89 per cent in summer 2024

Annual visitors to Nice: 5 million, making it the second most visited city in France

Nice Côte d’Azur Airport

Ranking in France: Second-largest, after Paris Charles de Gaulle

Number of passengers in July and August 2024: 3.46 million

Increase in annual passenger numbers since 2023: 3.7 per cent

Direct destinations in winter 2024: 76

Long-haul flights in winter 2024: 13 to North America and the Gulf countries

02.

New Bahru

Singapore

Though Singaporean retail and dining venue New Bahru opened to the public this summer, the roots of the project go back almost a decade. Hospitality entrepreneur Wee Teng Wen was visiting his wife’s art studio at the site, which sits in a quiet residential area north of the Singapore river. The former high school – a five-storey, C-shaped structure huddled around a courtyard – had been rented out to various tenants over the years but large sections of it, including the high-ceilinged school hall, still preserved some of their original features.

“I fell in love with the building,” says Wee. As he wandered its halls for the first time, he thought that the salmon-hued concrete structure, with its distinctive scalloped roof, could be turned into something remarkable. “When it came up for a master lease tender, we put our heart and soul into winning the bid,” he says.

As the founder of The Lo & Behold Group, Wee has spearheaded some of Singapore’s best bars and restaurants, including Tanjong Beach Club, The Warehouse Hotel and Odette. New Bahru is his most ambitious undertaking yet. It consists of multiple buildings on an indoor-outdoor site across an area of more than 20,000 sq m, with about 40 independent businesses spanning retail, dining and hospitality. (Wee describes it as a “creative cluster”.) There are frequent pop-up events, fairs and art exhibitions here, as well as a pre-school, a plant shop and an 55-key hotel and serviced apartments.

After an extensive renovation of the 83-year-old complex, New Bahru opened in stages. The first weekend of its soft launch provided a sneak peek of the transformation, much to the delight of the residents of the quiet, tree-lined River Valley. “In Singapore, what was really missing was a vibrant neighbourhood that you could spend a day just walking around and exploring,” says Wee.

You’ll find restaurants and shops among the area’s high-rise apartment blocks but the closest retail options were previously the glitzy mega-malls of Orchard Road, home to big-name global brands and chain restaurants – with little in the way of exciting independent ventures. By contrast, every business in New Bahru is a homegrown Singaporean brand. The founders can be found in their shops on most days, manning the tills, chatting to customers or helping in the kitchen.

“A lot of people say, ‘I live in that building’, and point over there,” says Keirin Buck, chef-owner of cocktail spot Bar Bon Funk (also part of Lo & Behold), as he gestures towards a nearby residential block from the terrace of the bar. Buck says that he is already welcoming regular customers who live within walking distance of New Bahru. “It’s nice to have people popping in at 22.00 to have a quick drink and then go home.” Wee views his tenants as “co-conspirators” and was careful when it came to who he selected. He sounds more like a fan than a property developer when he says that he wanted to assemble “the most talented entrepreneurs and designers in the country. Singaporean retail brands needed a little bit more visibility.”

He reached out to some directly, while others approached him as word of the project spread. The current list of tenants includes popular e-commerce businesses such as coffee specialist Morning, which decided to make the leap to bricks and mortar for the first time with New Bahru.

“A lot of our customers are design-centric people so it made sense to move here,” says Leon Foo, Morning’s ceo and co-founder. “The tenant mix couldn’t be better here. There are many creatives and we have cool neighbours.”

Other brands have expanded their footprint at New Bahru. Design shop Studio Yono, which used to occupy a tiny shared space elsewhere in the city, now has a spacious standalone shop here. The extra space has allowed its owner, Kaïa Nelk, to begin selling furniture.

“We paid attention to entrepreneurs who were wildly ambitious, the ones who would be able to create new, exciting and experiential concepts,” says Wee. Many retailers offer in-person workshops and classes that are exclusive to their New Bahru locations. The concentration of talent has led to several collaborations: womenswear brand Rye designed the staff uniforms for Atipico bakery, while Alma House’s serviced apartments are equipped with Morning’s coffee machines.

“This is like a vertical street block,” says Wee, squinting in the sun at the building that he has helped to revive. “If you laid all of this out on one level, you basically have an entire neighbourhood or village.”

newbahru.com

Meet the talent

1. Bessie Ye

Founder, womenswear label Rye

2. Leon Foo

CEO & co-founder, Morning coffee roasters

3. Wee Teng Wen

Founder, The Lo & Behold Group and New Bahru

4. Kaïa Nelk

Founder, design shop Studio Yono

5. Keirin Buck

Chef-owner, Bar Bon Funk cocktail bar

6. Ivan Woo and Angeline Goh

Co-founders, artisanal plant shop Soilboy

7. Giselle Makarachvili

General manager, Alma House boutique hotel and serviced apartments

03.

Jacumba Hot Springs

California

When three entrepreneurs decided to buy the faded Jacumba Hot Springs Hotel in the desert outside San Diego, they didn’t know that the deeds came with a dried-out lake full of old mattresses, a ruined 1920s bathhouse and a row of empty shops on so-called “Main Street”. “We basically bought a town in the middle of nowhere,” says Jeff Osborne, who stumped up much of the initial investment for the property. Since 2020, Osborne has worked with business partners and designers Melissa Strukel and Corbin Winters to restore the hotel, creating a smart bolthole a stone’s throw from the US-Mexican border. The hotel is now attracting new visitors to a dusty corner of California and reviving the area’s past glories.

When Jacumba (pronounced ha-koom-bah) was built in the 1920s, it was a roaring stop-off on the route from Arizona to California – a competitor to Palm Springs with four-storey hotels and supposedly healing hot springs that bubbled up from beneath the sand. But when a highway was built that circumvented the town in the late 1960s, it began to wither. A series of fires tore through much of its old landmark buildings and, as the decades passed, many families packed up and left. By 2020, when the entrepreneurs first arrived, only the 1950s-built Hot Springs Hotel and a liquor shop were still in business. Aside from visits by a few hippies and ufo-seekers (most people in Jacumba seem to have at least one sighting story), the old tourist trade wilted in the hot desert sun.

The hotel’s previous owners – a nudist couple with a reputation for throwing raucous parties – had kept the place going but it was in desperate need of renovation. Strukel was on a roadtrip at the start of the coronavirus pandemic and passed through Jacumba; she says that she immediately felt a connection to the place. When the hotel serendipitously came up for sale months later, the three entrepreneurs jumped at the opportunity to buy it. Then they moved out to the desert and set to work.

“Melissa and I hand-drafted every aspect of this property,” says Winters, unfurling the original pencil drawings in an office that was once an abandoned petrol station. Prior to moving here, the two designers had renovated a hotel in San Diego. “Even when you are your own client, you still lie awake at night questioning your decisions,” says Winters. “I would have a knot in my stomach before things were installed.”

The result of their efforts is a pueblo- style lodging with hand-moulded walls and hints of the high desert dwellings found in New Mexico. There are homely tiled floors in the bedrooms and an extraordinary attention to detail throughout, from the artful, Moroccan-inspired lights to a thoughtful selection of art and books that detail Jacumba’s story in every room. On a hillside just beyond the site, the group has kitted out an eight-bed lodge that has boulders in the back garden and striking views looking out to Mexico. It is already being hired out for retreats.

On the Sunday evening that monocle visits Jacumba, Clinton Davis, a fiddle player based in San Diego, is belting out cowboy tunes in the restaurant’s courtyard. Tables are laid under Afghan pine trees and residents of the area dine on rustic cross-border cuisine by candlelight alongside hotel guests. The weekend has been filled with DJ sets and open-air performances in the old bathhouse and, as the sun sets over ashen mountains, a few guests are having their last, slightly sulphurous dip of the evening in the mineral pools. These are fed by the underground hot springs, which are partly filtered in the town’s restored lake. It was cleaned up by the entrepreneurs, who had 75 native palm trees planted all around it. Idyllic at sunset, the lake has been a hit with the townspeople. Tim Burnett has lived here for most of his life and says that he previously couldn’t sit out on his porch because of the mosquitoes that would come from the once-stagnant water. “The phoenix has risen from the ashes with this place,” says Burnett.

The restored hotel and restaurant has brought some 60 jobs to the area, which has helped the three entrepreneurs to win over Jacumba’s residents, despite some initial wariness about “LA hipsters”. The team is hiring young people who wait tables in 10-gallon hats, while some among the check-in staff have been enticed to decamp here from nearby cities to greet guests in a charming trailer parked out front.

Even the nearby airstrip has had an uptick in arrivals. “We have prop planes landing here from Van Nuys Airport with Hollywood types; some are coming for the weekend, others just for lunch,” says the hangar’s owner, Roman Wrosz, who now takes hotel guests up for aerial tours and loop-the-loops in his glider.

The entrepreneurs are clear that the road to reviving Jacumba will be long and not without challenges. Occupancy levels have been good but they need to maintain momentum. The next step, they believe, is to find tenants for the shops on Main Street; they would ideally like a small grocery store that can sell fresh produce. “Whoever opens up here has to live here too,” says Strukel. “A lot of people need things wrapped up with a pretty bow before they can see the vision. But before any of this was done, we saw it immediately.”

jacumba.com