Trip 02 / Spain

Galicia, Spain

Once known to Romans as the ‘end of the world’, secluded inns and superior seafood now make Spain’s northwestern corner the beginning of an extraordinary escape.

Wild and windswept, Galicia’s landscapes are steeped in Celtic history, relating a story of Spain that reads rather differently from the more-often told Mediterranean tale. A wander along the footpaths that snake atop 600-metre-high sea cliffs facing the Atlantic, among prickly heather and mossy rocks, offers a literal and figurative breath of fresh air.

Galicia’s coastline is pocked with jagged rías, or estuaries, where sea and land intermingle and change with the tides. Thought to be the end of the world by early Romans, the remote Rías Altas area is dotted with fishing villages where Galicians still live up to a reputation as hardy seafarers. Now they are also seen as entrepreneurs and frontier folk with their own way of doing things. Our journey takes us southwest for three days, tracing the Iberian peninsula’s northwestern coastline from its tip. We take to high roads and zip between misty mountain hamlets and busy ports for a glimpse of how the world’s end became the centre of something much more exciting.

Day 1

Cariño to Cedeira

Our hopscotching journey across Galicia’s northern estuaries begins on the western bank of the Ría de Ortigueira in the town of Cariño. The tide is high as we approach and the multihued fishermen’s houses of the barrio marinero seem to hover on the salt-sprayed cliffs rising above the brackish waters where estuary meets ocean. In the late 19th century, Galicia’s rías were put on the map when fish and seafood caught in their waters began to be preserved in tins for international export. The demand for those conservas (including sardines, tuna and mussels) led to the development of a network of canneries next to village fishing ports.

While Cariño once had more than 20 such factories, today just one remains: La Pureza, a family-run affair founded in 1924. When we arrive, shoppers are queueing out of the door to pick up mackerel and conger eel preserved in olive oil. Conservas are still big business in Galicia, with exports rising in the past decade to €800m a year – more than half of the country’s exports in the sector. La Pureza’s 14 employees prepare and package fish according to traditional methods. Ana Docanto, our tour guide, is one of four siblings at the helm of the cannery founded by their grandfather. “We could have expanded by incorporating more machinery,” she says as we continue through the busy processing floor where red-and-yellow cylindrical tins are stacked high. “But we prefer tradition.”

A loaf of crusty bread and scallops in La Pureza tomato sauce make the perfect aperitivo during our stop at Cabo Ortegal, a 10-minute drive north from Cariño. From this cape’s red-and-white-striped lighthouse, you can take in spectacular views of the Capela da mountains, which descend into the roiling Atlantic. We head back into Cariño with fresh salt spray in our hair, ready for lunch at Restaurante Marea, where we tuck in to cockles in a creamy ginger-orange sauce, along with baked cod served over seaweed risotto.

After our meal, we drive into the Capelada mountains for 15km to reach San Andrés de Teixido. The sea-facing hamlet is home to a pre-Christian shrine. It was chosen by the Celtic ancients for its views, which remain divine to this day. There is even a saying in Galego, “He who goes not to San Andrés de Teixido in his lifetime will visit after death.” This is based on a legend that those who fail to venture up will be punished in their afterlives, reincarnated as lizards and snakes. Pilgrims must drink from each of the three spouts of the shrine’s fountain upon arrival in order for Saint Andrew to grant their wish.

Not one for superstition, monocle takes its leave, following the winding road down to Cedeira. This town, set on the eastern bank of the Cedeira Estuary, has been linked to whaling and fishing since the Middle Ages. Today it is known for its goose barnacles, or percebes. This delicacy must be hand-picked by nimble percebeiros, who face the risk of being struck by massive waves as they navigate the coast’s slippery rocks on foot to reach certain nooks; only in these can the tasty – but almost unforgivably ugly – barnacles be found. Restaurante Badulaque, a three-minute drive from Cedeira’s fish market, is the perfect place to sample freshly caught percebes, as well as langoustines, clams and spider crabs.

Cedeira’s seafront gives way to an elegant promenade where the Condomiñas river bisects the historic centre. It is a good vantage point from which to see how the town has evolved from fishing village to resort. As paddleboarders make their way upriver and children leap from the wrought-iron bridge into the waters, we approach our next stop. Os Cantís is a nine-room inn set in a restored townhouse, which was built in the early 20th century and once served as a priest’s residence. Hoteliers Fernando Cheda and Dolores López, together with interior architect Belén Sueiro, preserved the three-storey building’s gleaming white façade with wrought-iron terraces in a 2024 renovation. “It was more difficult and costly to build each floor with wood rather than concrete,” says López. “But while the process wasn’t very practical, it was in line with our ‘Take it or leave it’ philosophy, as well as our attention to detail.” Several rooms also feature the original stone walls. Outside, the river-side terrace is an ideal spot for savouring a glass of white wine paired with monkfish a la cedeiresa.

Day 2

Ferrol to A Coruña

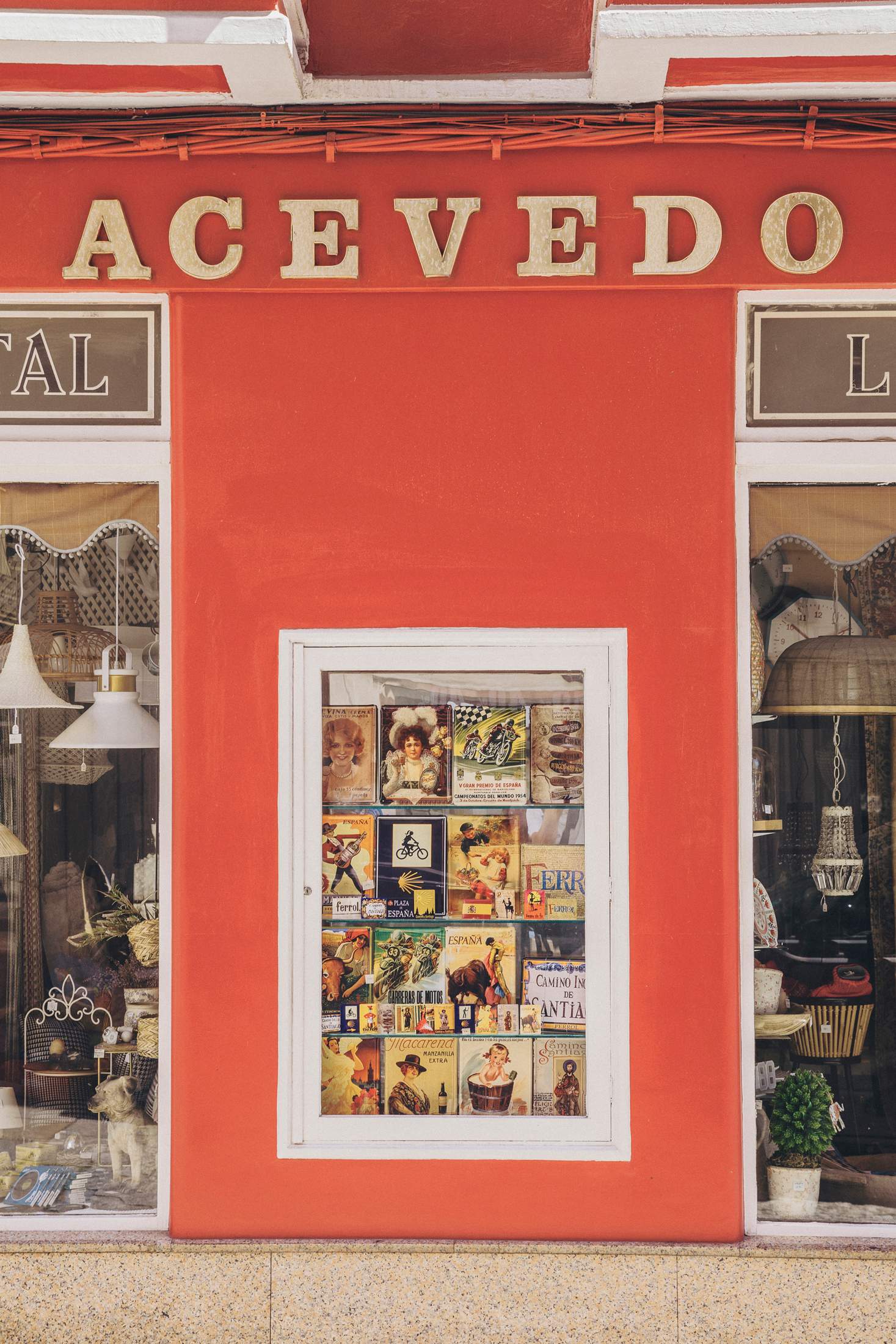

Leaving behind the quiet fishing villages we venture to the city of Ferrol, located on a narrow-mouthed ría of the same name. Thanks to its sheltered geography and deep natural harbour, Ferrol has been a shipbuilding hub since the early 18th century. The city’s Magdalena neighbourhood comprises a rectangular grid of lanes, featuring two and three-story residences built in the 19th and 20th centuries. Many of the upper levels of the houses here feature enclosed terraces, or galerías, inspired by the window-lined sterns of galleons. Galician architect Rodolfo Ucha Piñeiro contributed numerous art nouveau gems to the barrio, such as Casa Pereira, which features oversized circular windows that dominate its façade.

Strolling past the terrazas and shops that line the pedestrianised Rúa Magdalena, we reach an unusual threshold. It is made from white marble and inlaid with black block letters, reading “El Rápido”. The shop opened in 1922 as an ultramarino, a Spanish general store, which specialised in items such as chocolate, coffee and rum that came from overseas colonies. Owner Emilio Castro, an effusive 83-year-old, smiles from behind the oak counter and has a kind word for anyone who steps in. Some come to shop, others simply to check in on Don Emilio, as everyone calls him. “I am a neighbour,” he says.

Castro took over the shop from his father 66 years ago, and transforms the everyday act of shopping for groceries into something uplifting and memorable. At the behest of a customer, he gladly reaches across the countertop for an oversized glass jar of cascarilla, the shells of cacao seeds with medicinal properties, which few shops still sell. When customers leave, he bids farewell with a wink. And the jolly sage makes sure to warn us against prisas, or rushing, before we leave. “My friend,” he says. “Hurrying is of little use.”

But we don’t need to rush to savour a flavour usually associated with Portugal at the Lusitânia Café, one street over from El Rápido. The custard tarts there serve as a sweet reminder of Galicia’s proximity to the home of pasteies de nata, and their intermingling cultures.

Time is a recurring theme in Galicia. This is perhaps due to the proximity of the shore, where the ocean’s waves slowly carve the dramatic coastline of the region. Ramón María del Valle-Inclán, one of the most celebrated 20th-century Galician writers, wrote, “Nothing will be that did not come before. Nothing will be that does not belong to tomorrow.” Those with the time to contemplate this will surely see how the words reflect on Galicia itself.

Next stop is the bustling port city of A Coruña, where we meet watchmaker David Rodríguez. In addition to searching out and repairing fine analogue timepieces, he is responsible for maintaining the city’s oldest public clocks. His workshop, Relojería Nemesio, is steps from the city hall’s clocktower, where he fulfils his civic duty. “I must climb up there every day to wind it, including Saturdays and Sundays,” he says. “Would you like to see?”

An elevator takes us up three storeys from an ornate entrance hall, after which we ascend four flights of increasingly narrow stairs. From the clock tower’s pedestal, perched over the portico-lined Plaza de María Pita, we take in sweeping views of A Coruña’s rooftops and marina. Rodríguez tells us about the clock that dates back to 1909; he drove an initiative for its restoration in 2020.“Throwaway culture is not for me,” he says. “Rather than helping humans, fully automated objects actually limit our capacity to respond. I like to interact with life, with the world.” Loud thwacks fill the tower as Rodríguez pushes the hand-crank. When he comes to rest, he reveals that this old commitment could be aided by a modern intervention. “I’m working on a special adaptor, which could wind the clock using electricity, in case I can’t come up here on a given day.”

The restaurant 55 Pasos sits alongside the plaza. We take our seats at the wooden counter, which opens onto the kitchen. Chef Balázs Menyhard toasts bread over Japanese coals and his partner, floor manager Nataly Rodríguez, cuts paper-thin portions of cured beef from León with the deli slicer. Once the space’s eight tables are full, Rodríguez calls the diners to attention to announce the day’s dishes. From Thai green mango salad to Galician beef sweetbread, the menu demonstrates a commitment to using the best raw ingredients from the market on any given day. “Balasz has always said that we would end up opening a restaurant together,” says Rodríguez.

Cecina smartly plated at 55 Pasos

The pair met while working at The Berkeley hotel in London, with Rodríguez in management and Menyhard in the kitchen of its two-Michelin-starred restaurant. With their ties to the British capital – both also went on to work at Hedone in the city’s Chiswick neighbourhood – it came as a surprise when they ended up in Rodríguez’s hometown in 2019 and opened 55 Pasos.“We were told ‘no way’; there is no market in A Coruña,” says Menyhard. His fingertips massage an orb of burrata from Puglia, to which he will add the bright purple leaves of local basil. He interrupts his preparation to hop out of the kitchen and commence a lively conversation with a curious diner at a nearby wine fridge. They eventually settle on one of the restaurant’s biodynamic bottles. “I love wine, maybe more than food,” he says with a giggle. “But as a chef, I’m not supposed to say that.” As we tuck into a poppy seed-covered eggy bread for dessert – a recipe from Menyhard’s native Hungary – we can’t say that we are worried about the chef’s priorities.

A 20-minute drive brings us to Noa Boutique Hotel, on the opposite side of Ría da Coruña’s bay. Here we enjoy a fiery sunset from the rooftop infinity pool. Designed by local architectural firm Sinaldaba, the hotel’s 32 minimalist guestrooms all boast sea views. The 16th-century Castelo de Santa Cruz completes these vistas, 140 metres from the shore and reached via a wooden footbridge. Time has escaped us once again. Bed beckons.

Day 3

Buño to Fisterra

We start the day with a bracing swim, then check out. Green hills with leafy oaks and poplars dot the landscape as we drive southwest, past A Coruña. After 40 minutes, we arrive in Buño on the Costa da Morte.

This village is known for its oleiros, clay artisans who have been crafting their wares there since the 16th century. Ceramicist Alberto Lista was initiated in his craft by his father, who apprenticed under Lista’s grandfather. “Generational knowledge has been passed down in Buño as far back as anyone can remember,” says Lista, who greets us in a black, clay-specked work apron at the door of his shop, Alfarería Lista. He recently took over the establishment from his father, who is now retired. Though in the 1950s about half of the village’s residents were potters; today only eight workshops remain. “I decided to uphold this tradition,” says Lista.

Lista is part of a wave of young innovators bringing a design-focused approach to Galician pottery. Incorporating 3D-printing techniques has allowed him to produce increasingly thin clay objects for special commissions. “People are seeking simplicity more and more,” he says. “I like that. I’m quite basic myself. I work with simple colours and shapes that aren’t overly complex.”

We hop in the car for a quick 10-minute drive to reach O Fontán Restaurante for lunch. The restaurant is in a stonework casona, or stately residence, which the owners believe was built in the 19th century. It focuses on traditional local dishes such as grelos (broccoli rabe) and a supremely tender presa de cerdo celta, pork shoulder from a local breed of pig.

This part of the region is known as Costa da Morte largely thanks to the notable shipwrecks that took place in its rocky waters during the 19th century. Despite the preponderance of beaches – Galicia is home to more than 850, the most of any Spanish region – it is particularly important to choose sheltered coves and rías for swimming as currents here can be very strong.

We drive 15 minutes to Praia de Laxe before beach- hopping to the hamlet of Arou – a further 40 minutes southwest through hillsides rich in seaside pines. You can learn about local bobbin lace artisans in the fishing town of Camariñas. They are said to have learned their craft from Italian women who were rescued from a nearby shipwreck. Lucky for us, we have blue skies and calm waters ahead as we arrive in Fisterra. The name is derived from the Latin Finis Terrae, which is where the “end of the world” phrase comes from. This city’s lighthouse is the traditional conclusion to one of Christianity’s oldest pilgrimages, the Camino de Santiago, which dates back to the 9th century. Our pilgrimage, however, is of the culinary variety.

Fisterra’s historic port

It is well known across Spain that Galicia boasts spectacular fish and seafood. A few steps from the sands of Praia da Langosteira is the restaurant Tira do Cordel. The dining rooms in the former salting factory surround a large courtyard grill, where neat rows of wild-caught sea bass and scorpion fish are roasted to perfection. Try their almejas a la marinera (clams in white wine) or longueirón (a local variety of razor clam). After dessert we walk down the stone steps just outside the restaurant and onto the beach for some sun followed by a bracing swim. We stroll up the shore to a nearby hotel as the tide rolls in.

Hotel Bela Fisterra is a remarkable seafront lodging with a literary bent. Each of its 15 rooms have names drawn from sea-inspired literature, including Moby Dick and The Odyssey. Founded in 2018 by Pepe Formoso, the hotel uses energy drawn from solar panels and heating supplied by geothermal pumps, which help it to achieve zero-carbon emissions. Keeping the design locally inspired, Formoso enlisted A Coruña-based architectural firm Creus e Carrasco to create the minimalist structure that is intended to evoke the fish-salting facilities that were once prevalent along the shore. Inside, furniture designs by Galicia’s Isaac Piñeiro are modern while retaining a joyful spirit and a sense of place that is utterly unique to the area.

Laying on a lounger of the hotel’s terrace, overlooking the water as the sun’s dying rays tinge the clouds pink and orange, Galicia feels at once modern and ancient. Somewhere worth exploring, regardless of the time of year. “There’s nothing more beautiful than observing a storm from the water’s edge,” says Formoso. “The vitality of the salt air in Galicia can and should be enjoyed all year.” —

Galicia address book

Day 1

stay

Os Cantís

This family-run inn in a restored turn-of-the-century townhouse brings chic modernity to a little-visited part of the Galician coast.

hoteloscantiscedeira.com

eat

Restaurante Badulaque

Visit this restaurant in the Casa do Pescador for the freshest seafood. This is where local fishermen meet after hauling in the day’s catch.

Rúa Area Longa, Cedeira

shop

Conservas de Pescado La Pureza

This canning facility, now run by the founder’s grandchildren, is the perfect place for buying gourmet treats to go, such as tinned fish and mussels.

lapureza.es

Day 2

stay

Noa Boutique Hotel

Not only does each room in this minimalist accommodation boast sea views but it is possible to enjoy a bathtub soak while looking out across the water thanks to cleverly designed glass partitions.

noaboutiquehotel.com

eat

55 Pasos

Reserve well in advance: diners come from near and far to enjoy chef Balázs Menyhard and floor manager Nataly Rodríguez’s unique take on dining. Each meal is a celebration of the best market ingredients, it will not soon be forgotten.

Rúa Nosa Señora do Rosario, 9

shop

El Rápido Ultramarinos

While this type of corner grocer was once ubiquitous in Spain, the ultramarino is now a dying breed. Visit Emilio Castro in this centenary business to find that friendly service and quality products can still go hand in hand.

Rúa Magdalena, 139

Day 3

stay

Hotel Bela Fisterra

The only literary lodging in the region is also an architectural gem with sustainability at its core. Visit this seaside oasis off season to partake in its vibrant cultural calendar.

belafisterra.com

eat

Tira do Cordel

Old-school hospitality is front and centre at this local favourite, where grilled sea bass is king.

tiradocordel.com

shop

Alfarería Lista

Potter Alberto Lista puts a modern spin on earthenware vessels, elevating cookware to the status of sculpture.

alfarerialista.com