Elections / USA

Balance of power

At a febrile time for the US, we meet three figures who are speaking up about social justice, civil rights and the power of fair reporting.

1.

Chris Wallace

News anchor

Fox News presenter who likes to ask difficult questions – and is not afraid of Donald Trump.

Polling day on 3 November will mark the 11th presidential election that Chris Wallace, the anchor of Fox News Sunday, has reported on. “Since I started doing this in 1980, with Reagan and Carter, people have said, ‘This is the most important election of our lifetimes.’ It’s really become a cliché,” he says. “This, in my long experience, is a pretty special and challenging year. We have this terrible pandemic, we’ve had a painful economic collapse and we have serious racial tensions. This does feel more consequential than other elections.”

That’s about as decisive an opinion as he is willing to offer. Fox News, particularly its prime-time broadcasts and opinion-led programmes, is often accused of stoking the divisive tone now prevalent in political discourse. Yet those accusations are rarely levelled at Wallace. Throughout his decades-long career as a political interviewer – he was previously an anchor at NBC and ABC – he has faced criticism from both sides of the political divide. Bill Clinton claimed that Wallace had “a little smirk” on his face while interviewing him in 2006 and Barack Obama refused to grant him an interview. Meanwhile, Donald Trump has described him as “nasty and obnoxious”.

“This, in my long experience, is a pretty special and challenging year”

“I find it a depressing commentary on the state of journalism today,” says Wallace from his home in Annapolis, Maryland. “To hold both sides to account is kind of an oddity. I think that news coverage has become swept up in that tribal view of the world. Fox News has contributed to it but so has CNN, so has MSNBC, so has The New York Times. It is kind of lonely – to be equally tough on both sides.”

Lonely or not, it’s an approach that earned Wallace an invitation to moderate the first of three presidential debates between Trump and Democratic nominee Joe Biden in Cleveland, Ohio, at the end of September. “It’s quite different [from] being an interviewer,” Wallace says of the task. “It’s like being the referee in a prize fight. They’re the two combatants and you’re there to just make sure it’s a good, fair fight.”

What makes a good interview question is something that has preoccupied Wallace for years. It’s a craft that his late father, Mike Wallace, was recognised for during his own career as a correspondent for 60 Minutes, the august news-magazine programme. “I try very hard, and I think my father tried very hard, to make the question respectful, fact-based and pointed – and hard for the person to escape.”

It came as a surprise when Trump agreed to sit down with him for a lengthy interview in July in the gardens of the White House. Wallace pressed him on everything from his handling of coronavirus to his falling polling numbers and his cognitive abilities.

“I’ve never seen a bigger difference between the private man and the public figure than with Donald Trump,” says Wallace. “In private he’s a very nice man; he’s polite. Then there’s the public Donald Trump. He certainly has gone out of his way to write mean tweets about me, sometimes in quite personal terms. He says, ‘You’re not your father.’ He’s said that over and over. The first time, maybe, it stings a little. After that, it becomes noise.”

Wallace’s new book ‘Countdown 1945: The Extraordinary Story of the Atomic Bomb and the 116 Days That Changed the World’ is published by Avid Reader Press and is available now.

2.

Jane Fonda

Activist

The actor and campaigner on the importance of peaceful protest – and how she has used her platform for social change.

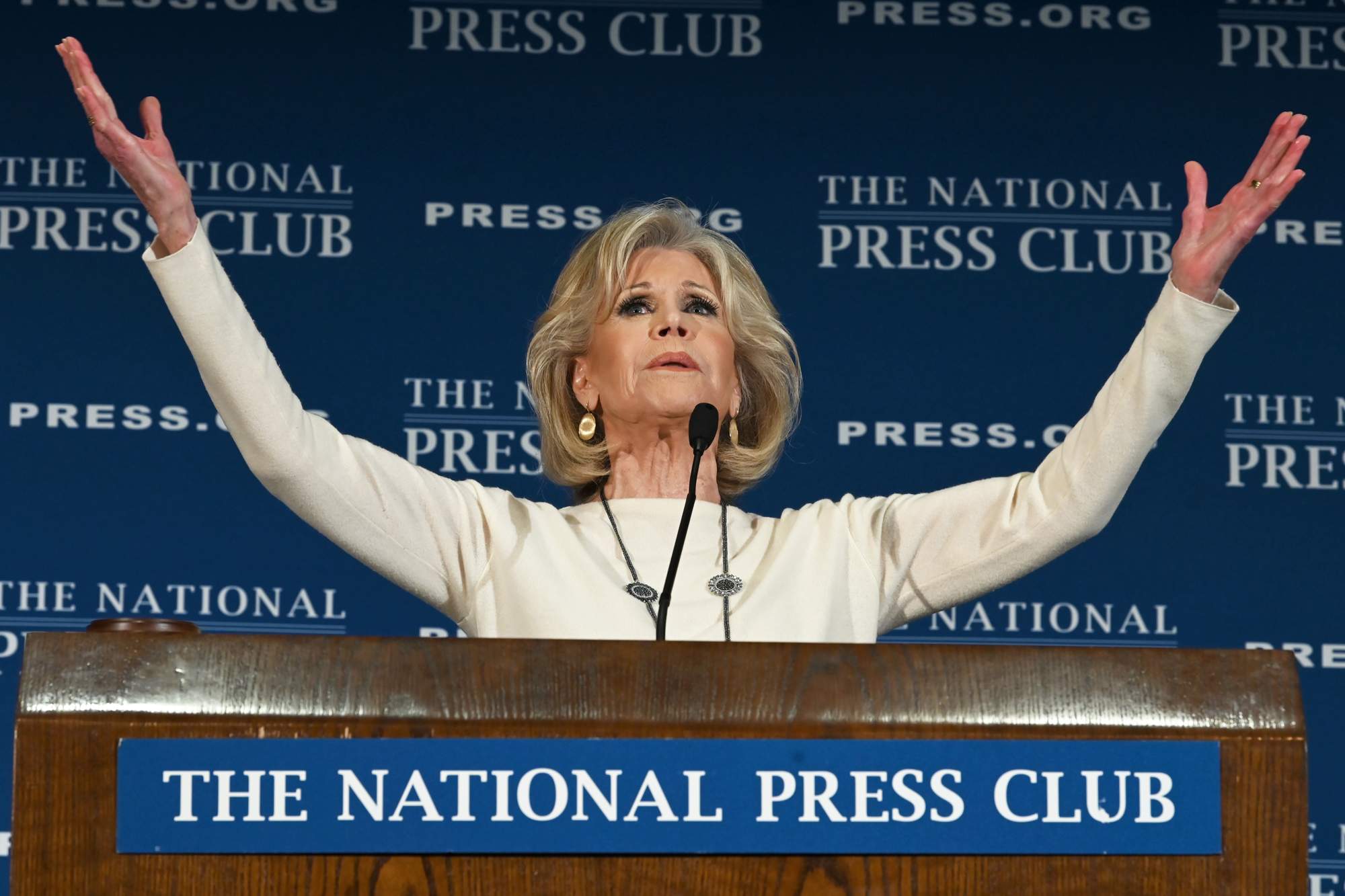

Imploring journalists to improve their coverage of climate change last December

Jane Fonda – actor, activist and former home-fitness impresario –isn’t a stranger to getting arrested. “I have been handcuffed before and put in jail before,” she says, speaking from her home in Los Angeles. The last time she was confined to a prison cell was in 1970 when she was charged with drug smuggling following a tour of anti-Vietnam War rallies in Canada. The charge was spurious and overseen, it was later revealed, by President Nixon, who was angry at the potency of Fonda’s anti-war activities.

But when a police officer placed her hands behind her back and fastened them with white plastic zip ties on a Friday in October last year, the experience, she says, felt new. “I just felt so empowered,” she adds of her arrest for protesting on the steps of the Capitol. “Now I’m almost 83, and [it was] painful. But I knew why I was there. I knew there would be a lot of press coverage.” She was right. Fonda’s arrest marked the beginning of Fire Drill Fridays, a weekly protest in Washington established by her, a team of friends and environmental campaigners. Its goal is to quicken the tempo of the climate debate, to spur government to act and to offer herself up as a role model for other would-be demonstrators. The objective, says Fonda, was to get arrested for civil disobedience week after week.

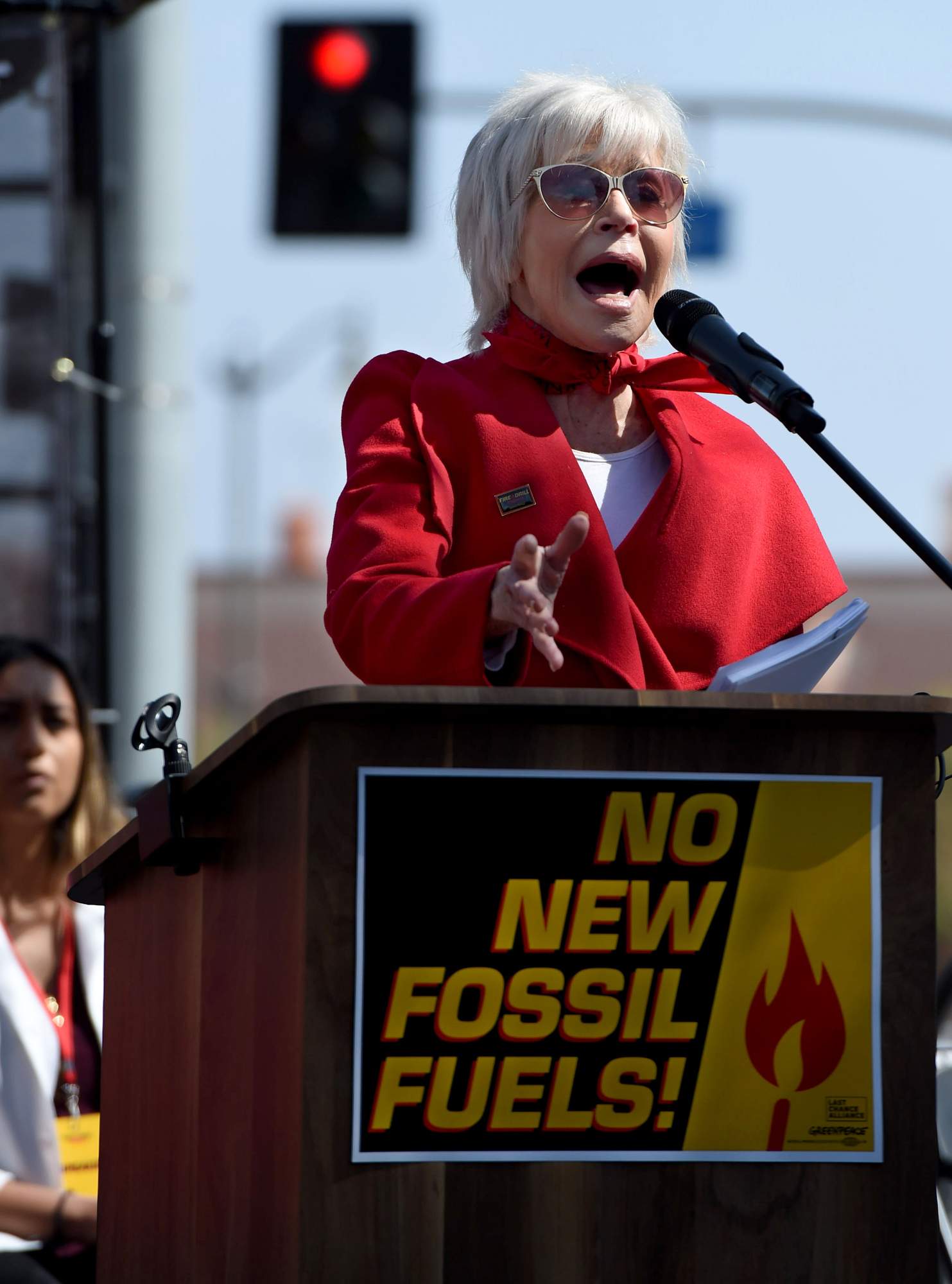

On the stump in Los Angeles in March

On the pro-abortion frontline in 1989

“I don’t need attention for me personally,” says Fonda, in between sips of iced tea. “The reason the attention is important is that it makes people realise the urgency of the climate crisis. We have 10 years to cut our fossil-fuel emissions in half, which is an awesome, unprecedented task.”

It’s hard to think of a moment of activism, from the 1960s onwards, when Fonda hasn’t been in its midst – or at its helm. In the early 1970s she began financially helping the Black Panthers and raising awareness on their behalf. In 1972, Fonda famously posed for a police mugshot at the 1970 Academy Awards with her fist raised, the Panthers’ signature posture. Her home workout videos, released in 1982, were launched to raise money for The Campaign for Economic Democracy to end economic injustice in the US, a subject close to her heart. “We’re a democracy but we’re not an economic democracy,” she says. It is the issue that earned Bernie Sanders Fonda’s endorsement earlier this year.

She is now supporting Joe Biden. She says that his candidacy doesn’t mean that the push for a more progressive agenda in US politics has been lost, as some of Sanders’s supporters claim. “We have to be ready, the minute – please, God, please – that Joe Biden is elected, to force him to create resilience in this country,” she says. “I don’t think people realise how close to the edge most Americans live, pay cheque to pay cheque. That’s inexcusable.” Fonda’s activism doesn’t end there: she has worked to dispel the stigma around mental health (her mother, Frances, committed suicide when Jane was 12). She has fought for women’s rights in the workplace, to end domestic violence and to lower teenage-pregnancy rates. She has challenged society’s view of the elderly and in 1979 delivered part of her best actress Oscar speech in American Sign Language.

“It’s nice to be able to reach your old age realising that you’ve managed to have impact in a lot of different ways. But things don’t change suddenly”

Along the way Fonda has become a role model to many but a villain to some. In 1972, Nixon’s administration called for her to be tried for treason after she posed for a photograph in Hanoi in the midst of the Vietnam War. In the picture she is sitting on an anti-aircraft carrier, its barrel directed upwards, apparently towards US military planes in the air. Fonda has since apologised for the image and for its depiction of hostility towards US soldiers, rather than the war itself. But it made her a divisive figure and earned her the nickname “Hanoi Jane”.

“There’s toxic anger and there’s healing anger,” she says, pointing to the Black Lives Matter protests in the US, which were rekindled by the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May. Those demonstrations, according to some tallies, have become the largest mass-protest movement in the history. “It feels like a turning point,” she says. “There’s something about this moment that got people out into the streets. Not just because they’ve been shut off for so long. But the pandemic has pulled the Band-Aid off the profound systemic injustice and inequality in this country.”

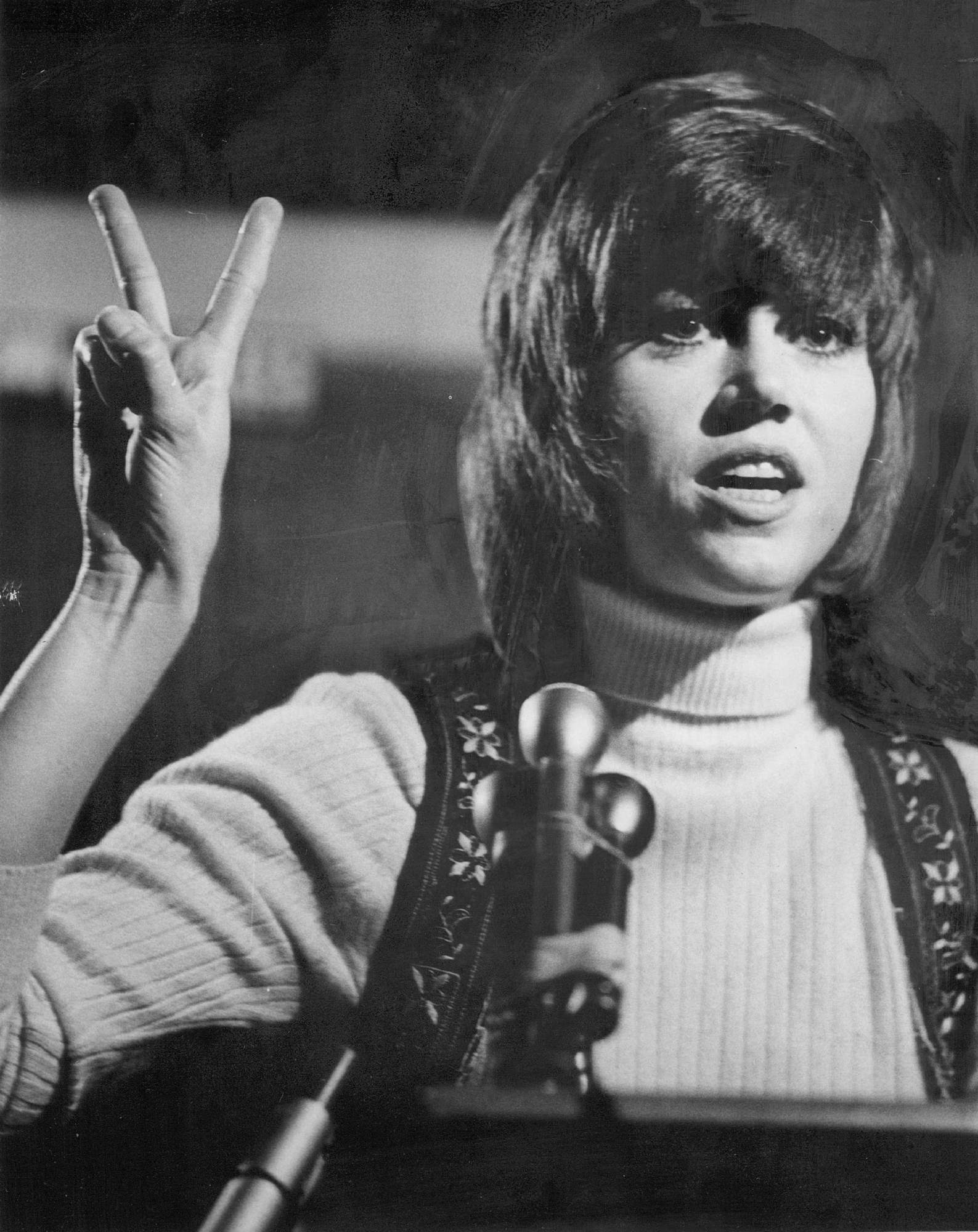

Voicing her opposition to war in 1970

Advocating peaceful protest for 50 years

The forthcoming election has also spurred things on. “The most important thing to do is vote,” she says. Members of the Fire Drill Fridays team, she adds, are currently working through voter rolls, informing people if their name has been struck off the list and guiding them through the process of re-registering ahead of the election.

How does Fonda measure her campaigns’ successes? “Well, I don’t measure it,” she says. “It’s nice to be able to reach your old age realising that you’ve managed to have impact in a lot of different ways. But things don’t change suddenly. They can appear to do so because of all the work that’s going on under the surface. So you can’t get impatient and you can’t demonise someone who doesn’t agree with you – because the work is going on.”

Fonda’s latest book, ‘What Can I Do? My Path From Climate Despair to Action’, is published by Penguin and is available now.

3.

Theaster Gates

Artist and urban planner

A man who breathes life into neighbourhoods and explores African-American history on civil rights challenges that still lie ahead.

In the early 2000s, Theaster Gates, the Chicago-born urban planner, ceramicist and artist, was offered a gift by a friend who owned a recycling business: a pile of old fire hoses. “And, I swear to God, they sat in my studio for three or four years,” he says, speaking from his base at the University of Chicago.

Until, that is, a conversation with friends stirred a memory. In May 1963 students began marching peacefully through the city of Birmingham, Alabama, demanding an end to discrimination against black people in the US. The public safety commissioner ordered the police to disperse the demonstrators with powerful jets of water pumped through fire hoses.

“So the hoses, for me, became a way to enter the contemporary and conceptual art world with this coded, embedded, seemingly indecipherable message that could also carry the truth of racism,” says Gates. “I live with both of those truths – of wanting to make good art and to tell the story that is not fully told.” Gates revisits that idea time and again in his work, which spans an array of forms.

Urban planning and community development projects are developed through the Rebuild Foundation, which he established in 2009 to revitalise Chicago’s under-invested neighbourhoods. His live performances evoke the black choral music of the churches he attended when he was a child. Other works are made in clay or with ephemera, such as the fire hoses, which became the basis for his landmark Civil Tapestries series, the work that effectively launched his career. Large, wooden panels are overlaid with vertical strips of the hoses in their original colours: mottled beige, smudged yellow, deep red and bright blue. Several pieces are now in public and private collections around the world, including London’s Tate Modern.

“We’re reminded again that in 2020 the challenges that exist [are] not very far from 1967 or 1968. Racialised violence happens against peaceful people all the time”

The Tapestries are his commentary on the lived experience of the civil-rights movement, what remains of it and what has ebbed back into the established order during the decades since. “The ambition of the civil rights project didn’t completely fulfil itself,” says Gates. “Those sit-ins and protests that led to the civil-rights movement, then a black-power movement, then a black-is-beautiful movement didn’t totally redeem themselves. And all we are left with are these trinkets, these trophies that say, ‘I was there.’”

The realisation that the material the hoses are made from doesn’t break down over time, says Gates, was potent – a symbol of the permanence of institutional violence against people of colour, told through the implements that carried it out. “It’s really unfortunate that the Civil Tapestries continues to be relevant,” he says. In particular, he adds, when protesters were forcibly cleared from Lafayette Park near the White House with tear gas for Trump’s photo opportunity with a Bible in June.

“That part of my work feels like an ongoing monument to the existence of racialised violence. We’re reminded again that in 2020 the challenges that exist are not very far from 1967 or 1968. Racialised violence happens against peaceful people all the time, all over the world. I think Trump’s call to history, if you will, is reigniting white people’s right to a kind of racialised difference in America.”

Gates has become most famous for the spaces he has designed in which black life is intended to unfold. “They were not works of art, exactly,” he says, referring to projects such as the Dorchester Art and Housing Collaborative, established in 2011. It began as a public housing project in a once-dilapidated building; the site now includes an art and community forum, 32 affordable and market-rate townhouses, which allows artists and existing residents to live and work in a collective space. “[These are] durational projects,” says Gates. “They allow people to see what happens if black resources and black influence are used in a black space. And if that project is successful, others will take up the charge.”

His celebrated Stony Island Arts Bank – a cultural space, archive and community hub on Chicago’s South Side, built within the shell of a derelict bank – opened in 2015. It was an exercise in a different way of redeveloping a neighbourhood. When Gates struggled to secure funding for the project, he took a novel approach. He created his own bank bonds, engraved into stone fragments from the bank’s façade, and sold them at Art Basel, raising nearly $1m (€840,000). “I’m an abstract urbanist,” he says. “Because I want to make poetry, in a way.”

What motivates his work in the charged environment of 2020’s election campaigns? “Two things seem to be playing out for me,” he says. “Is it possible, within my artistic practice, to raise the flag that something is afoot, that there’s a challenge among us, that there’s a monster in the building? I try to do that in the most poetic ways possible. I’m concerned about injustice, the possibility of equity, the challenges of economic disparity,” he adds. “I have tactical strategies for ensuring that the excess that I have access to, that people around me benefit from that. I try to keep it one-to-one, you know – me to my community.”

Gates’s solo show ‘Black Vessel’ runs at the Gagosian Gallery in New York until 19 December.

Images: Thomas Prior, Getty Images, Lyndon French