Urbanism / Global

The change-makers

Whether they’ve required minor nips and tucks or major new infrastructure, the following five urban interventions have cleverly reimagined their neighbourhoods and cities for the better.

1.

The neighbourhood rethink

V&A Waterfront, Cape Town

In 1990, as South Africa entered the final throes of apartheid, a small group of developers launched an ambitious project to transform Cape Town’s largely derelict harbour into a tourist, retail and residential development. Today, the Victoria & Alfred (v&a) Waterfront welcomes more than 24 million visitors a year.

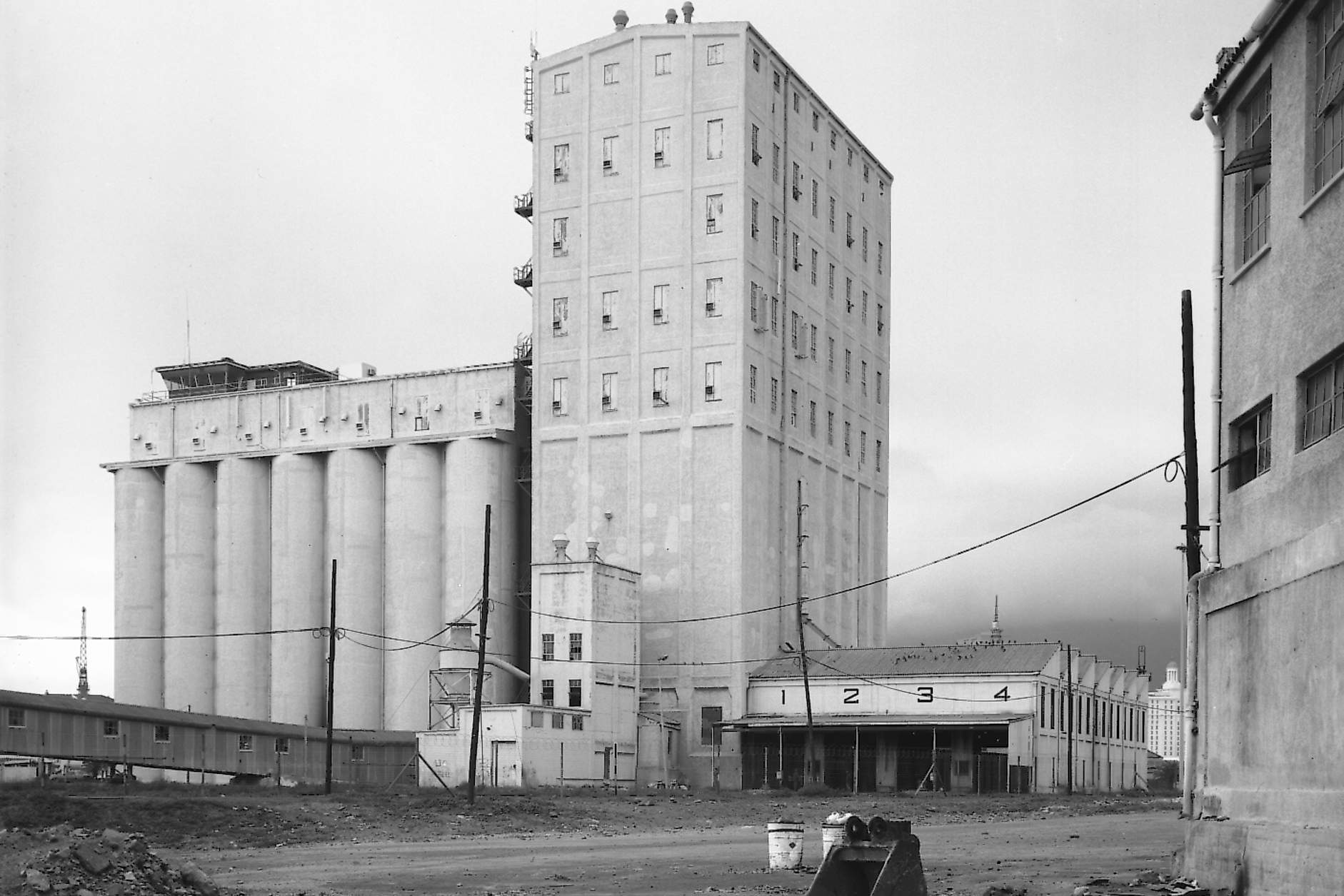

before: Long-abandoned grain silo on Cape Town’s waterfront

after: Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Mocaa)

But when David Green, a Brit who had headed up port regeneration projects in Glasgow and Liverpool, took over as the v&a Waterfront’s ceo in 2009, there was a sense that it was losing its way. In a city still beset by the legacies of apartheid spatial planning, it risked becoming an exclusive playground of a wealthy few. “Our vision was to salvage the soul and authenticity of the waterfront, with the principle that it has to be a place for locals first,” says Green. This has been a central tenet of recent mixed-use developments at the v&a, most notably the Silo District and the Canal District, unveiled in 2017 and 2018 respectively. Both projects have repurposed the shells of historic buildings and provided public space in a part of the city that had been empty.

The focal point of the Silo District is Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Mocaa), housed in a long-abandoned 20th-century grain silo. Meanwhile, the Canal District’s pedestrianised walkways provide the missing link between the waterfront and the city centre. “We want Cape Town to be walkable,” says Green. “It’s about creating safe, inclusive and interconnected neighbourhoods.”

Under Green, the waterfront has also won a slew of awards for best environmental practices and provided a home for more than 400 small businesses. “There is a responsibility to try to right some of the wrongs of the past,” he says. “We want to serve as a kind of microcosm of what that could look like.”

Monocle comment: Simple measures such as Mocaa’s free entrance on Wednesdays for African passport holders ensure that the v&a Waterfront draws locals and tourists.

2.

The small change

Precollinear Park, Turin

Thinking small can generate a big return. Just ask self-taught urbanist and Turin resident Luca Ballarini. Where most locals saw an abandoned stretch of tram line along Corso Gabetti, Ballarini saw an opportunity. The owner of a creative agency used his imagination to turn an 800m-long disused strip of track and platforms that divided two neighbourhoods into a welcoming patch of green where adults and children can walk, listen to lectures or munch on a panino.

before: Disused platform

after: Park for people to gather

“After lockdown, urbanites need to enjoy the open air,” says Ballarini. “We’ve spent too much time of late in the virtual world. People need to be out in the physical world and interacting.” He secured a permit from the city to occupy the space, which includes a section on a bridge over the River Po, with lounge chairs and yellow benches made from cargo pallets. To beautify the area, a team removed weeds and brought in wooden planters with flowers. Inaugurated this summer on a shoestring budget of €15,000, a portion of which was crowdfunded, the Precollinear Park project has been a catalyst. There are live music performances, outdoor yoga classes, author readings and a farmers’ market.

What’s more, seating and greenery can be whisked away to an on-site container should the city decide to reinvest in transport in the future. This cleverly conceived initiative is run by the non-profit Torino Stratosferica, headed up by Ballarini, which organises the annual Utopian Hours urbanism festival every autumn in the Piedmont capital to discuss schemes to improve livability in big cities.

Monocle comment: Not all transformations require deep pockets and years of planning; change can be the result of a go-it-alone initiative.

3.

The central link

Yagan Square, Perth

Railway tracks, more than any other form of transport infrastructure, can create impenetrable barriers. For 140 years, Perth’s centre – its business hub – was severed from Northbridge, the neighbourhood housing its museums, galleries and restaurants. The railway was a dividing line between commerce and culture. But that changed in 2018 when newly submerged tracks allowed for a pedestrian plaza, Yagan Square, to link the two.

“If you go back in time, to the early 20th century, you’ll find that the government architect then was pursuing the idea of relocating this train line that had dissected the city,” says Adrian Iredale, one of the architects behind Yagan Square. But if the government knew for more than a century that a change was needed, why did it take so long to make one? Well, the high cost of such a project meant that political will was low and it would take a bold politician, such as the state’s former premier Colin Barnett, to spearhead the project.

before: Unsightly transit station serving little use

after: Pedestrianised square full of life

“It took a candidate brave enough to look beyond the immediate need for hospitals and education to say, ‘We have a moment in time where we’re wealthy enough to do the bold propositions that everyone will benefit from long-term,’” says Iredale. “To make such a call, one that changes the way the city works, I think there has to be some political courage.”

The outcome of this courage is a city that’s once again connected – and one that has a new heart. Until the pedestrian plaza, market hall, amphitheatre and play area opened, Perth had lacked any sense of centre. It seems that the creation of this new public space was not just an effective patch-up job for the city but successful heart surgery too.

Monocle comment: Urban interventions might not always be the most politically popular propositions but pursuing a sound plan can create a lasting legacy.

4.

The revitalisation

Nordhavn, Copenhagen

Copenhagen’s most extensive transformation project in recent years has seen the once gated area of Nordhavn, a former maritime hub, go from abandoned, gritty industrial port to one of the city’s fastest-growing districts. Behind the site’s revamp, which led to a twelvefold increase in local population over the past four years, is urban development company By & Havn.

before: Industrial buildings on Copenhagen’s port

after: Neighbourhood transformed

ceo Anne Skovbro has overseen the project from the start in 2009, both as head of the company and the city’s former planning director. “We opened a completely new area and we wanted it to look like Copenhagen,” she says. “We kept old warehouses and built with bricks.”

One of the main objectives in providing the Danish capital with a central and newly built neighbourhood was for the area to naturally flourish as a lively urban space. “We envisioned Nordhavn as a classic European neighbourhood, which combines homes, a high street and offices,” says Skovbro. Through private- public partnerships, By & Havn provided a variety of street-level businesses, ensured that one in 10 properties qualify for social housing, and developed outdoor areas for the community. Today, Nordhavn is also home to some of the country’s leading architecture and design firms, which have contributed to the creation of more than 11,000 jobs. And with the area’s planned expansion across yet-to-be-built artificial land, Skovbro’s work is far from over. “We keep expanding Nordhavn with the same question in mind: how do you develop an area for the people?”

Monocle comment: Left untouched, former industrial sites are a wasted opportunity. Reimagining such areas offers cities room to grow.

5.

The community project

Peace Tree Parks, Detroit

Eric Andrews is from a Detroit neighbourhood that has long been a textbook case of urban blight. It has an abundance of vacant lots and empty houses and, for much of Andrews’s upbringing, until Whole Foods arrived nearby in 2013, it was a designated food desert too.

before: Empty, unused stretch of land

after: Thriving garden that feeds the community

“Growing up in this neighbourhood, I had two grocery stores to go to and you wouldn’t want to buy produce from either of them,” says Andrews. On top of this, he adds, the area remembers the painful effects of the 1967 riots, which saw bloody confrontations between residents and the police, and resulted in decades of vacant blocks; bankruptcies following the 2008 recession made things worse.

It’s a combination that inspired Andrews and some friends to purchase two vacant blocks on 14th Street in 2015. Here they launched Peace Tree Parks, a non-profit that transformed the land into a community garden. The site now harvests some 90kg of produce every month, feeding 250 of the garden’s neighbours, who enjoy the aubergines and pumpkins for free. It might seem like a flawed business model but Peace Tree Parks hopes to improve the area, not profit from it. “The prices at Whole Foods were not affordable for the majority of people who live here, so we were still posed with the same problem [I had growing up],” says Andrews. “That motivated me to just give the produce away.”

And while it has ensured that residents can access quality food, it has also changed the physical nature of the neighbourhood for the better – another community garden launched this year. “Now, when people pull off their street, they don’t see grass up to their knees, and boxes and tires stacked up,” says Andrews. “I think that makes people who live here feel better about their community.”

Monocle comment: Not all work requires significant infrastructure. Sometimes addressing a basic requirement in the most straightforward manner is the way to go.

Images: Alamy, Jan Søndergaard, Ryan Deblowski