Affairs: Defence / Rhode Island

Bay watch

The Ocean State has become a hub for defence businesses that are helping to lift its economy out of the red and into the blue.

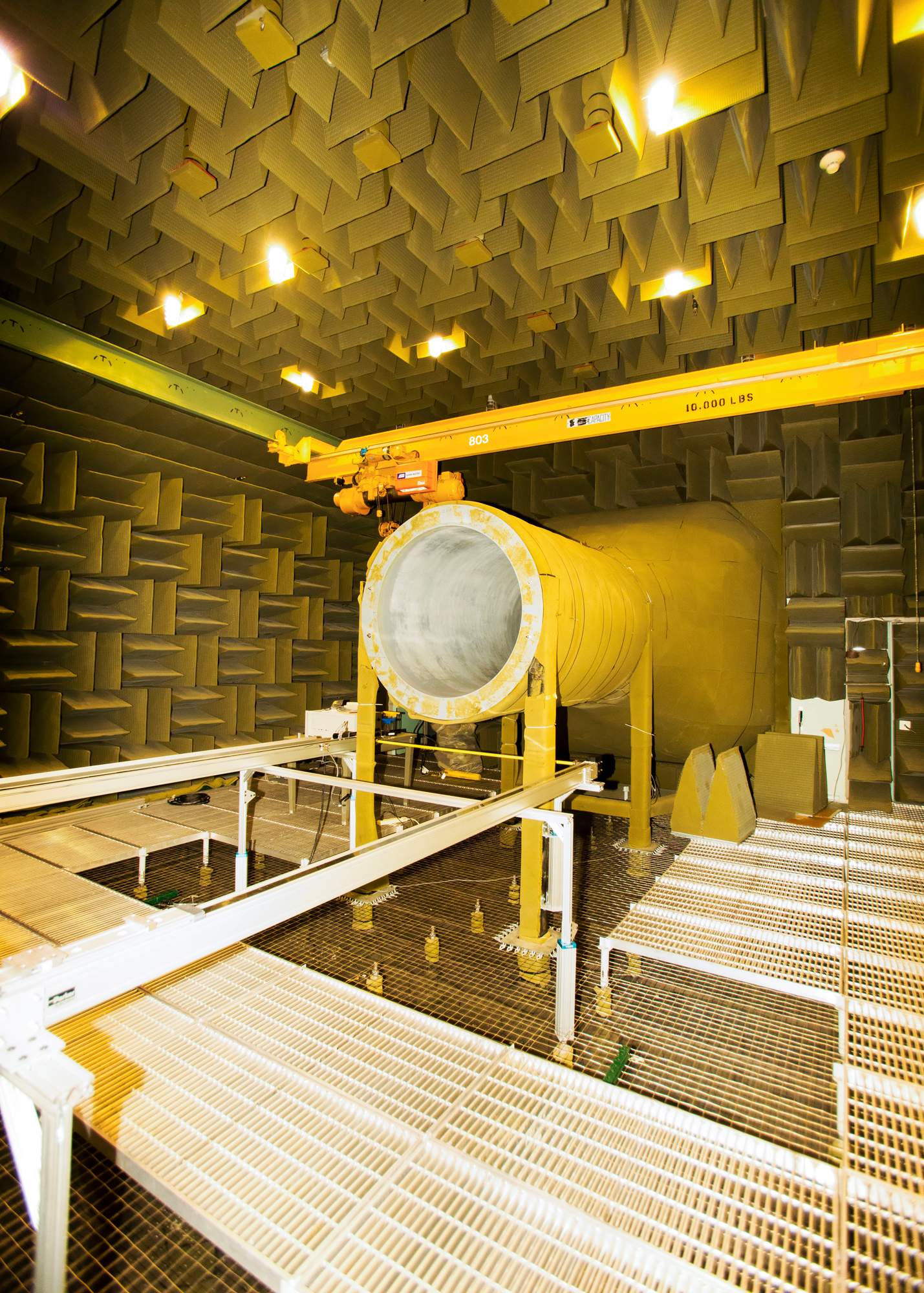

Wind tunnel at the Naval Undersea Warfare Centre

Drones are trialled at sea from Rhode Island

It’s a choppy day in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, as a pair of rocket-shaped drones skip over the swell. They stop abruptly, noses pointed skyward in the dark water, awaiting a signal to dive into the deep. “You just throw these boys in the surf and off they go,” says Ian Estaphan Owen, a Welshman who served in the UK’s Royal Navy and worked for US defence manufacturers Raytheon Technologies and Lockheed Martin before co-founding Jaia Robotics in December 2020. In a historic bay-side workshop, where Burnside rifles were assembled during the American Civil War, Owen developed this small, inexpensive craft that autonomously collects real-time data about conditions beneath the waves. “There’s also a payload option,” he says, running a hand along the bright red body of the Jaiabot. “You could put a bit of c-4 [explosive] on it and really annoy somebody.”

Jaia Robotics attracted more than $1m (€1.7m) in seed funding last year and its Jaiabot drone has caught the US military’s eye as a tool for finding safe spots for amphibious operations when the waves are high. It’s one of the many firms and start-ups that are clustered on Rhode Island’s coastline, an emerging blue economy of maritime expertise, ideas and manufacturing.

Jaiabots are autonomous vehicles that can operate in ‘swarms’ of 12

Jim DeSousa, head of finishing at Composite Energy Technologies

For 2024, the Pentagon has requested an $842bn (€769bn) budget – the largest in US history – and embarked on one of its biggest peacetime procurements. While America’s major defence players will reap the benefits, the Department of Defense (dod) is also looking to grow its network of small defence businesses across the US – and Rhode Island is showing the way. Beyond the quaint, cobbled streets and Gilded Age mansions of Newport, a growing cadre of factories and laboratories are supplying the US Navy with undersea technology, from vessels that can withstand depths of 6km to onboard systems for submarines.

Rear admiral Shoshana Chatfield, president of the US Naval War College

Pacmar Technologies, for instance, has expanded its historic canal-side workshop where it makes prototypes and inflatables for the navy, as well as carrying out undersea work that it must keep tightly under wraps. “Being in Rhode Island gives us access to a wealth of partners to grow our undersea line of business and ensures that we are staying in lockstep with the navy’s needs,” says Pacmar’s chief technology officer, Priya Hicks. Down the road in Quonset Point, General Dynamics Electric Boat is building the next generation of American submarines, the Columbia class, which is billed as a potential game-changer in undersea warfare, even if it won’t be delivered until 2031. “We need to have a strong workforce pipeline to ensure that people can get the training and skills that they need to fill those well-paying submarine manufacturing jobs,” says Rhode Island state senator Jack Reed, who also chairs the powerful Senate Armed Services Committee. Turn on the local TV channels and there are regular adverts recruiting people to build the new submarines. “These jobs are critical to the future of our national security,” Reed tells Monocle.

Fabrication plant at the Naval Undersea Warfare Centre

All around Narragansett Bay, which is crowded with sailboats and sunseekers in the summer, history is repeating itself: the US Navy tested torpedoes in these waters during the Second World War and the military is again looking at hardware developed on this coastline to help turn the tide of future conflicts.

At the centre of the blue economy is the Naval Undersea Warfare Center (nuwc), a secretive US military installation perched on the eastern side of the bay, which is handing big contracts to local manufacturers. Home to about 3,600 civilians, mostly scientists and engineers, and only 20 military personnel, the nuwc is where the US Navy comes to solve a deep-sea problem: its specialists work in artificial intelligence and its physicists know how to take advantage of the bubble that forms as a torpedo enters the ocean. Jason Gomez, the nuwc’s chief technology officer, drives us around the base, keeping close tabs on everything that we see and hear. “Our folks work directly with the fleet on a daily basis,” he says. “They understand what the commanders in the leadership need, right down to points in a mission kill-chain.”

The nuwc team is not used to welcoming visitors, especially foreign media, and none of our photographer’s cameras are allowed on base. Instead, Monocle must use the navy’s own equipment and our shots are scrutinised. “These vehicles are at the forefront of the navy’s future,” says Mike Ansay, supervisor of the unmanned undersea vehicles (uuvs) workshop at nuwc. “Most of the uniformed navy hasn’t yet been exposed to what we’re working on down here.”

Almost everything in Ansay’s basement workshop is highly classified: objects of various shapes and sizes are swathed in sheets of tarpaulin. Undersea drones will play an increasingly important role as deployable listening posts that lie in wait and patrol the depths, monitoring hostile submarines and distracting incoming torpedoes without putting sailors in harm’s way. At nuwc, there’s a Snakehead drone, the largest such vehicle yet to be launched from a nuclear submarine – to the public’s knowledge, anyway. It is currently unclear whether this hefty machine will ever go into full service. Though intended for surveillance, it also looks as if it could be adapted to pack a punch. In the torpedo launcher lab, a new configuration is put through its paces; the head engineer leans on a decommissioned Tomahawk cruise missile as a blast of compressed air emits from the ocean-blue test barrel, which gets a thumbs-up from the crew. “In the 1990s a lot of work was done on quieting but now we need to renew that technology and get even quieter,” says John Laliberte, who is standing in the propulsion lab’s anechoic chamber, which is designed to eliminate all echoes. “The adversary has become a lot more complicated.”

Undersea warfare is, by its nature, stealthy work – the motto of US submariners is “alone and unafraid” – yet some of the labs appear ossified and unchanged since the Cold War. But those who work with the nuwc say that a fresh energy is blowing through the facility as it engages more with local firms. Many now test their latest products on the base’s stretch of waterfront and are increasingly called upon to find solutions to naval dilemmas.

US Navy vessels retrieve test drones from the bay

Graduation day at the US Naval War College

“Rhode Island is a small place with a long history of innovation,” says Julie Kallfelz, director of Northeast Tech Bridge, a non-profit formed in 2019 that tries to cut some of the red tape that otherwise prevents new products developed in the private sector getting out to the fleet. Kallfelz cites a recent example of a Rhode Island firm that devised an onboard system to 3D-print handwheels – ubiquitous aboard any naval vessel – in case one should break at sea. Having hosted the America’s Cup 12 times between 1930 and 1983, Rhode Island can also tap into a long tradition of boat building. Eric Goetz made race-winning sailboats for decades and now the firm he co-founded, Composite Energy Technologies (cet), uses the same methods to mould uuvs out of carbon fibre for the navy. The huge 16.7-metre-long hull of one lies in pieces on the factory floor. Though Goetz’s team also mould architectural forms for Renzo Piano and theme-park rides, the military is now cet’s biggest customer. “We end up doing everything on these uuvs – the naval architecture, the calibrations for how it floats – from soup to nuts,” says Goetz. “And the navy guys love that.”

All of this is not just about growing the blue economy. In February the US secretary of the navy, Carlos del Toro, warned that China has a larger fleet than the US, as well as the shipyards to further increase its advantage. Simply put, America no longer has the manufacturing muscle that it did at the height of the Cold War. The decline of small defence manufacturers in recent decades has curtailed supply chains that would be essential if the navy ever needed to mobilise suddenly. What’s happening in Rhode Island are tentative steps to address that. “It’s about putting more resilience into the system,” says the aptly named Colonel Erik Brine, director of defence sector r&d initiatives and operations at the University of Rhode Island. The university’s research foundation is leading on millions of dollars in new funding from the dod this year to help accelerate local maritime firms and give them access to the latest equipment.

Rhode Island is also home to the US Naval War College, which was founded in a coastal cottage in 1884. Now, it’s the Pentagon’s think-tank for US sea power and recently they’ve been wargaming the question of whether larger navies win wars. There’s no single answer, say academics: China has more warships but its nuclear submarines are outpaced by US technology – for now. “They’re the right type of subs to do what they want with them though, which is the unification of Taiwan with the mainland, and ensuring that the US and its allies can’t come to Taipei’s assistance,” says Alfred Turner, an associate professor of joint military operations at the college.

Professor Carol Prather, a specialist on Chinese maritime strategy, says that there’s a tendency for military planners to fight past wars. She points to the use of drones in Ukraine as a sign of how conflict is evolving. The US Navy plans to have 150 unmanned surface and undersea vehicles in its fleet by 2045, so an industry gold rush is coming. Further up the New England coast, ambitious defence start-up Anduril is building a submersible in Massachusetts that it says can conduct missions autonomously for 10 days at a time, while Swedish firm Saab is opening a vast new factory in Rhode Island that will build uuvs that the navy will use to train sonar teams to identify undersea threats. “Maritime domain awareness is shaping the evolution of underwater and surface vehicles,” says Erik Smith, president and ceo of Saab Inc. “The geography of Rhode Island couldn’t be better for testing the kind of vehicles that we envision building and deploying there.”

It’s fitting that this is a state where people have long sought privacy and solitude. The relationships in the undersea economy, between business and military, are anchored in discretion; workforces are vetted and tech is only explained on a need-to-know basis. As one engineer told Monocle: “The navy gives us the dimensions, they tell us where the wires go, but when it comes to the actual gizmos inside, we don’t know what they’re for.”