The Agenda: Defence / Global

The sky’s the limit

The lack of Sudan evacuations shows up nations, Norway takes the Arctic Council chair and the latest drone technology from Portugal.

War is an accelerator of technology. The Ukraine conflict is doing for drones what the 1991 Gulf War did for cruise missiles and the Second World War did for jet engines: it is ushering an emergent technology into the mainstream. Ukraine’s military is using Portuguese aerospace company Tekever’s kit for “recognition and intelligence missions”. “A year and a bit of war in Ukraine feels like 10 years of information,” Ricardo Mendes, Tekever’s ceo, tells monocle. “Previously you had large military drones but this war has shown that ordinary people can use the technology.”

Other Tekever operators include the navies of Portugal and the UK, and the Italian Coast Guard, for which the firm’s drones monitor whales and dolphins in the Pelagos Sanctuary. In March the UK gave Tekever a contract for its ar5 and ar3 drones for surveillance of the English Channel.

Tekever is now working on the arx, which will be among the largest uncrewed vehicles in the air. “It’s a significant leap,” says Mendes. “We don’t look at arx as just a plane. It’s a computing platform.” A potential application is swarming: the deployment of smaller drones from a larger “motherdrone”. The possibilities are immense, especially for militaries – if they can keep up. “The typical military procurement curve means that you’re using last decade’s technology,” says Mendes. “That needs to change – and whoever doesn’t change will be at a tremendous disadvantage.”

tekever.com

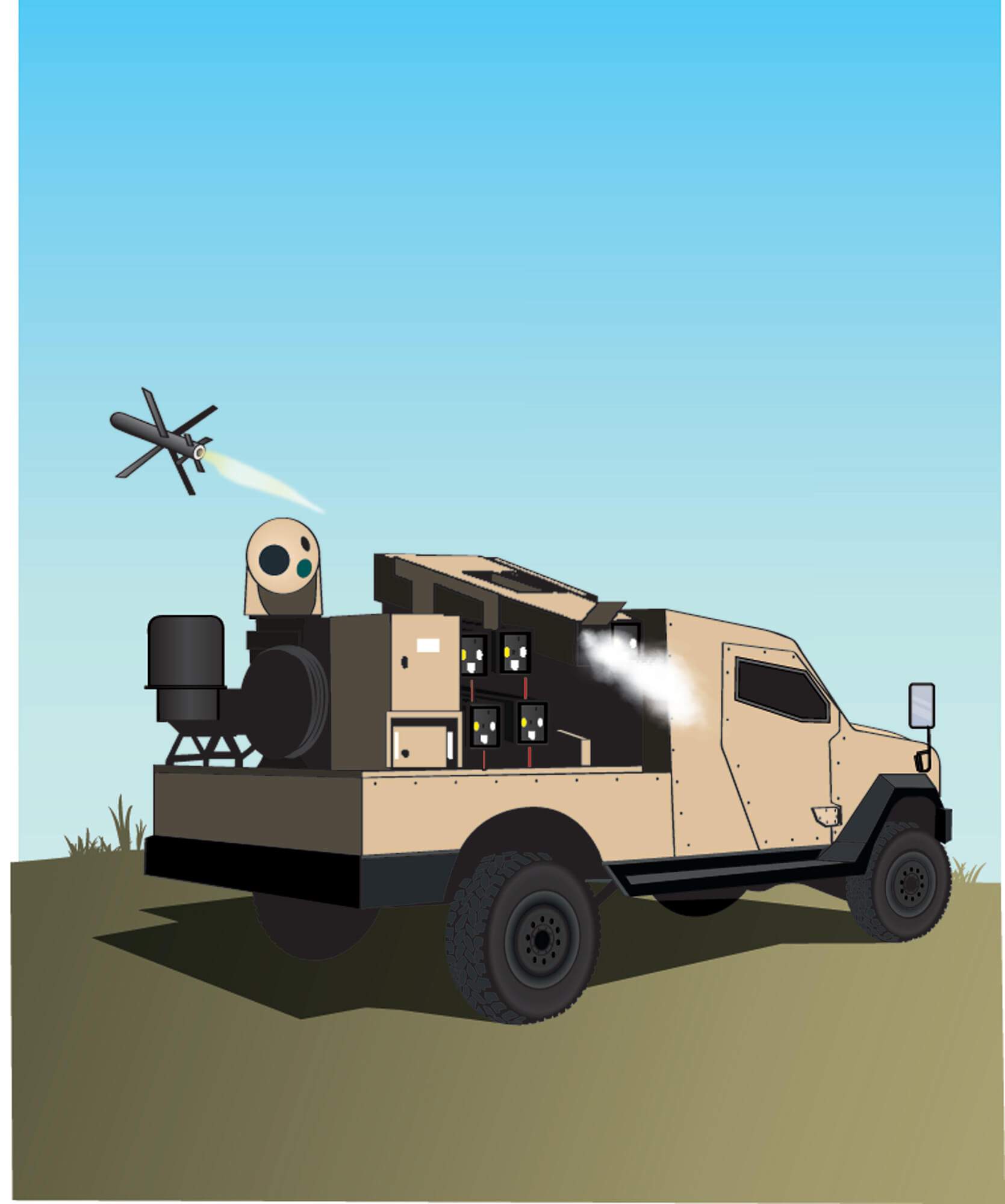

In the basket: Spike antitank missiles

Who’s buying: Greece

Who’s selling: Israel

Price: €370m (approx)

Delivery date: tbc

Israeli state-owned defence contractor Rafael’s Spike missile is a popular weapon that is already used by 39 countries. Greece’s order includes variants designed to be launched from the ground or from helicopters and naval vessels. For obvious reasons, many European countries are taking a heightened interest in antitank provisions (Croatia and Switzerland will also soon be Spike owners). Israel has become something of a market leader in defensive-missile systems. Greece’s purchase of the Spike comes on top of Finland’s acquisition of the Israeli air-defence system David’s Sling.

Q&A

Admiral James Foggo

Dean of the Center for Maritime Strategy in Arlington, Virginia

Admiral James Foggo led the US naval forces in Europe and Africa until 2020 and, before that, Nato’s Allied Joint Force Command Naples. He tells monocle about the geopolitical struggle that is under way beneath the waves.

What is the ‘fourth battle of the Atlantic’?

Since the war in Syria there has been a resurgence of Russian presence in places such as the Mediterranean that is primarily felt underwater. The new battle is in the North Atlantic and the tributaries feeding into it from the Arctic, the Baltic, the Med and the Black Sea.

Can the US still build ships and submarines as rapidly as it did in the past?

Manufacturing is starting to return to the US but since the 1960s we have lost 14 shipyards that construct ships for our navy. We should be producing more warships but we can’t do that quickly because of the industrial base’s limitations.

How significant is the Aukus pact?

It is crucial. It’s about more than just nuclear submarines: it sends a message to authoritarian regimes that have encroached on island chains [in the Pacific] and transformed them into military bases.

For more on the new era of naval competition, turn to page 73 for a report on Rhode Island’s underwater weapon manufacturers.

Finding true north

With a conspicuous lack of ceremony, Russia ceded its role as chair of the Arctic Council to Norway on 11 May. The handover marked the beginning of a much-needed fresh chapter for the eight-nation body, whose activities were paused soon after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Since the Cold War, nations in the High North have increasingly pulled together on science, maritime navigation and environmental management. Indigenous people, meanwhile, have had a bigger seat at the Arctic Council’s table than at most multilateral forums. All of this makes resuming dialogue at the council a pressing concern for many, from Inuit leaders to researchers studying permafrost. In March, Norway’s Arctic affairs ambassador, Morten Høglund, outlined Oslo’s priorities at a symposium in Anchorage, Alaska. These, he said, are climate change, oceans, sustainable economic development and working with the people of the Arctic. None of this is ground-breaking but given that Høglund’s audience included delegates from Belgium, Estonia, the EU, Germany, Japan, Poland and Singapore, it suggests that economy and environment are a welcome change of subject from militarisation, which has dominated Arctic discussions for the past year. As Nato, Russia and China bolster their security postures in the High North, reinvigorating the Arctic Council could help the region to regain its lustre as a global model for peace, diplomacy and co-operation.

Given that Russia has more territory above the Arctic Circle than any other nation, engaging with Moscow is inevitable. As such, the council could become a place for cooler heads to reset relations in the wake of the Ukraine conflict. But Høglund is tempering expectations. “Our measurement of success is that the Arctic Council has survived intact and that work on all relevant areas is ongoing – not necessarily at the level that it once was but at an adequate level,” he tells monocle. “A functioning Arctic Council without Russia isn’t meaningless but it has a lot less value.”

The FOREIGN DESK

andrew mueller on...

International rescues

There is no sterner test of a country’s commitment to the protection of its citizens than a sudden need to extract them from peril. The deterioration of the situation in Sudan in April presented many governments with this daunting challenge. Such operations are a risk first and foremost to the personnel who have to carry them out but they also present dangers to the prestige of the nation concerned.

The US’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 made it look heartless and inept. Such an impression was fair enough, as it was both of those things – and the country’s response to Sudan suggested that it wasn’t a fluke. While special forces flying Chinooks from Djibouti evacuated US embassy staff in Khartoum, other Americans in Sudan received little more than vague directions to possible overland routes. Shortly before shutting up shop, the embassy tweeted that it was “not currently safe” to evacuate US citizens – to which those citizens would have been entitled to retort, as the city erupted around them, “That’s why we’re enquiring.”

The UK also received poor reviews for its early efforts. The Times reported that British staff at the Khartoum American School who contacted the Foreign Office were simply told to seek guidance online. The beleaguered teachers were flown out by France, whose response seems to have been as generous as it was efficient. As of this writing, France has rescued more non-French than French. (Spain and Germany have also evacuated non-citizens.)

The French airlift, Operation Sagittarius, also demonstrates the coercive potential of being perceived as a serious military power, whether one fires a shot or not. France’s media confirmed that Emmanuel Macron personally contacted both of Sudan’s rival warlords before deploying troops. One suspects that during these calls, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and General Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo did rather more listening than speaking.

These are moments when a nation state can demonstrate the best of itself to the world and, in so doing, remind its own citizens of what it is there for. Though the circumstances were different, Israel’s raid on Entebbe airport in Uganda in 1976 to rescue hostages taken by Palestinian militants and German revolutionary weirdos was a significant statement of intent: we look after our people, wherever they are, whatever the odds. When the soldiers returned, the then prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, told them, “Not only did you save lives; you changed the image of Israel.”

Andrew Mueller hosts ‘The Foreign Desk’ on Monocle Radio. Listen live at monocle.com/radio every Saturday at midday London time or download as a podcast.

illustrator : Jésus Prudencio. images : Getty Images, ALAMY