Culture: Art / Paris

Kit for a king

France might have dispensed with royalty but the firm that kits out its official residences reigns supreme.

Few would guess that a cluster of modest 17th‑century buildings in the French capital’s 13th arrondissement could be home to some of the country’s most precious furnishings: thrones that once belonged to Napoleon, a Marie Antoinette armchair taken from the Tuileries Palace and a carpet donated to Notre-Dame Cathedral in 1841, salvaged from the fire that ripped through the building in 2019. Their custodian, Mobilier National, is the diplomatic body that furnishes the Republic’s official residences – both at home and abroad – with art, tapestries and furniture, but it was once the monarchy’s personal makeover service. While much has changed since then, it still has a prestigious role to play – and plenty of regal possessions.

France’s government residences, including the Élysée Palace, Hôtel de Matignon and Palais-Royal – plus a number of ministries, government agencies and embassies – all continue to benefit from the services of Mobilier National, which became part of the Ministry of Culture in 1959.

Established by King Louis xiv in 1663 as a means of keeping the monarchy’s furniture and art in one place, Mobilier National has always been about both logistics and politics. The creation of this repository enabled the monarchy to keep track of its fabulous possessions and bolstered the work of Gallic craftsmen at a time when Dutch and Italian goods were threatening to eclipse France’s output.

The country’s modern-day leaders make use of the organisation too. “President Macron and his wife, for example, have distinctly contemporary taste, so they asked for furniture that reflected this after taking over from François Hollande,” says Emmanuel Pénicaut, Mobilier National’s director of collections. Luckily, the couple had a lot to choose from. “We have some very valuable pieces here, either because they were used by a significant historical figure or because they were made by a highly respected French designer.”

These pieces include chairs by master carpenter Georges Jacob, a bespoke suede- upholstered armchair created for former president Georges Pompidou, a Serge Manzon cabinet and tapestries by Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Le Corbusier. “Every piece holds artistic significance as well as a piece of France’s history,” says Pénicaut. The repository contains more than 130,000 items, some dating back to the Middle Ages. It also houses three textile workshops – the Manufacture des Gobelins, Manufacture de Beauvais and Manufacture de la Savonnerie – where 100 technicians and 50 apprentices work to create new artefacts.

Mobilier National’s employees ensure that every item in the collection stays in the best condition possible. The foundation also comprises a dyeing workshop and seven restoration ateliers that specialise in cabinets, chandeliers, carpets, tapestries, bronze and gold furniture, lighting fixtures and objets d’art. While the French might be known for their deft statecraft, it appears that the country’s diplomats and politicians are clumsier on the domestic front: Mobilier National repairs about 1,500 pieces every year. “Just this morning we found a lamp in the Élysée Palace that wasn’t working, so we swapped it out to be reconditioned while Mr Macron is away,” says

“The Danish appreciate the art of tapestry making but there are no more tapestry manufacturers there, so they came to us instead”

Pénicaut. “It’s important that the Palace is in immaculate condition, as the president welcomes diplomats there on a regular basis.”

With such an vast collection, organisation is essential. “Every piece is numbered so that we can easily locate it and it’s all organised in chronological order, according to the era in which it was made,” says Pénicaut. “Before we put something back into the stock, we check that it’s in good condition. If it isn’t, we restore it and inspect it regularly to check for signs of degradation. We always need to reassure ourselves that everything is still there and in optimal condition, because it could be needed at any time.”

As with many of Paris’s institutions, space is an ongoing issue. “A lot of the pieces aren’t in the stock at any one time because they’re in various different state outposts,” says Pénicaut. “But even so, we have to keep a precise inventory of our reserves because they fill up very quickly.” In recent years, Mobilier National has started acquiring new pieces at antiques markets, auctions and galleries, as well as creating its own designs. While they never sell their creations, they occasionally accept diplomatic commissions from other countries.

Atelier where cabinets are restored

Key facts and figures

1,500: Pieces repaired at Mobilier National in 2023.

130,000: Items in Mobilier National’s collection, including lights, carpets, textiles, paintings, furniture and etchings.

340: People working at Mobilier National.

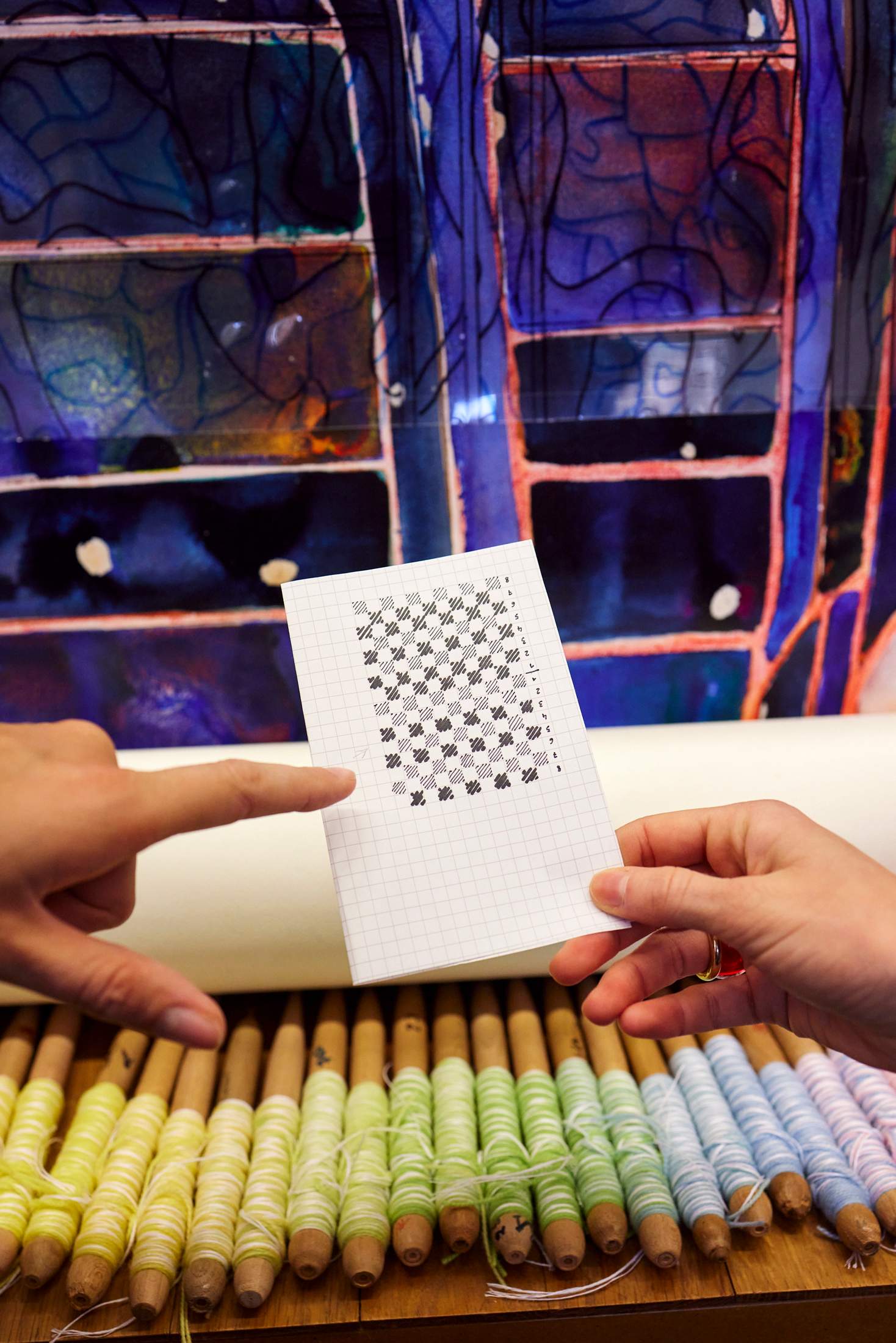

When monocle visits the Manufacture des Gobelins, six artisans are absorbed in weaving a set of 16 tapestries for a medieval castle newly acquired by the state of Denmark. Their work has just started and the project will take five years to complete. “The Danish very much appreciate the art of tapestry making but there are no more tapestry manufacturers there, so they came to us instead,” says Pénicaut.

As far as domestic commissions go, eight weavers from the Manufacture des Gobelins and the Manufacture de Beauvais have been working on a three-part tapestry with French-Iranian author Marjane Satrapi since 2021. Commissioned to celebrate the 2024 Olympic Games, the artwork features the Eiffel Tower, the Olympic flame and breakdancing, a sport that makes its debut at this summer’s Paris showcase. “People tend to think of tapestry weaving as an ancient craft but we want this project to show that the art of tapestry making is also a contemporary one,” says Pénicaut. Though it was founded more than five centuries ago, Mobilier National’s objective remains the same: to ensure that France’s heritage is never a thing of the past. — mobiliernational.culture.gouv.fr