Expo / Global

Stick to the recipe

We celebrate restaurants that have nourished diners across generations.

At their best, great restaurants nourish their neighbourhoods. As venture-capital-backed “concepts” flood the market – with their touchscreens, staff with scripted responses and value-engineered menus that cater to profits rather than to people’s tastes – our most cherished independents need our support. The way we eat might change but the qualities we seek in a restaurant remain the same: we want a pleasant environment where we will be looked after and can eat well. But isn’t there also something especially reassuring in the practised manner of a waiter keeping order as an evening heads off script? Or a maître d’ who remembers your name (and your dog’s), as well as your favourite bottle? Or a chef patron who can sense whether you are in the mood for a chat or want some privacy?

Running a restaurant across decades and generations might not be the straightest path to wealth, fame or riches but the most enduring establishments offer their communities sustenance in more ways than one. These have the common ingredient of care, as well as the grit to resist fads and the temptation to constantly redecorate. Without them, our cities would lose something integral.

So, is there a recipe for prolonged success? First, forget rotating menus and guest chefs. Second, read on for our celebration of the hospitality holdouts that have thrived by catering to needs that won’t change with the seasons. ––

the crown jewel

Kronenhalle

Zürich

Behind its unassuming façade, Kronenhalle offers a lesson in how food is only part of what makes a meal outstanding or a restaurant remarkable. And you can start learning the secret to its success for the price of a potato rösti and a crisp glass of chasselas. The Gaststube has stood the test of time by sticking to its core principles rather than attempting to offer something for everyone – there are no “concepts” or tasting menus here. That sense of continuity and the service of something bigger is summed up by the wall-mounted portrait of Hulda Zumsteg, who founded the restaurant in 1924: she attentively gazes down at the tables, wearing pearls and an elegant black gown. Her late son, Gustav, continued to serve her takes on French and Swiss classics, while bringing in impeccable art. Visitors can dine alongside the work of painters such as Chagall, Miró and Picasso (many of whom were guests) with their bratwurst or chateaubriand.

The restaurant’s current director, Dominique Nicolas Godat, and his team ensure the upkeep of seamless service that’s solicitous but never shy of reminding visitors of the house etiquette (no video calls, no screens, no athleisure, please). Its head chef, Peter Schärer, has been part of the kitchen staff for more than 30 years. This respect for tradition is crucial to Kronenhalle’s allure. Its guestbooks might brim with the names of illustrious patrons but this isn’t a place for grandstanding. Indeed, regulars tend to use the side entrance, rather than the main one.

Date founded: 1924

Signature dish: Zürcher Geschnetzeltes (veal in white-wine sauce). Save space for mousse au chocolat with double cream.

Covers: 172.

Employees: 95, including 30 kitchen staff.

Maximum height permitted for dogs: 60cm (so that they can fit under the table).

Known for: Not changing things. Both the signature dishes and the placement of the art are stipulated in Gustav Zumsteg’s will.

How it has held out: Even a weekday lunch has an element of performance and the customer isn’t always right. Kronenhalle has its own rules and customs, and staff aren’t shy to gently remind guests of how to behave.

the mid-century master

Café Prückel

Vienna

Much has happened over the centuries since the emergence of the Viennese coffeehouse but it has proven to be a remarkably resilient institution. An inherent Gemütlichkeit (or cosiness) invites you to linger and, unlike in many modern cafés that can be quick to shoo you out, you can linger over a cup of coffee. The flipside? Service tends to be slow and the waiters studiedly condescending, if not outright curt, especially towards those who aren’t clued up on the rules of engagement. But that’s all part of the charm.

With its vast windows, Café Prückel on the western edge of the city’s Ringstrasse excels in most departments. It opened in 1903 under a different name and in the bright, gaudy style of artist Hans Makart. In 1955 architect Oswald Haerdtl spruced up the interior to include cheerful pastel hues and spindly low-slung furniture, helping the café to stand out from its wood-panelled peers.

Thomas Hahn, one of the three new co-owners who took over in January following the 62-year tenure of Christl Sedlar, is intent on preserving what he first found at Café Prückel. “Tradition is very important here,” he says as elderly Viennese ladies descend on their Stammtisch (regular table) for a game of cards. “It is my third restaurant but my first with this kind of past.” The only real changes slated are to the kitchen equipment; the classic fare on offer, from the schnitzel and goulash to the cakes, will stay the same. Now, where’s the waiter with that coffee?

prueckel.at

Date founded: 1903.

Signature dish: Pastries and cakes, including Kaiserschmarrn (shredded pancakes) with jam or whipped cream.

Employees: 40.

Known for: Its charming neon sign and the unusual brand of Viennese mid-century design within.

How it has held out: A willingness to go with what works rather than reshaping things to fit modern trends has kept Café Prückel from becoming mere tourist fodder. The interior is listed; Unesco also added Vienna’s coffeehouses to its Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2011.

the neighbourhood favourite

The Odeon

New York

“We were young and it was kind of a fluke,” Lynn Wagenknecht tells monocle about the success of the cafeteria that she and Keith McNally took over in 1980. An arts graduate with no hospitality experience, Wagenknecht eventually bought out McNally and brought in two partners, Judi Wong and Steve Abramowitz (the pair behind the West Village’s Café Cluny), who helped to make The Odeon the lively Tribeca institution that it is today.

The restaurant is a constant in the ever-changing neighbourhood and takes all comers: thirsty locals, judges and lawyers from a nearby courthouse, celebrities who cosy up in the red banquettes for a martini and steak frites. For Wagenknecht, being here for the community matters. The doors remained open to shelter people and serve firemen during the September 11 attacks.

Changes to the interiors have been small: the cafeteria still has the original panelling and globe lights from 1932. “But our goal has always been to keep things relevant and appealing,” says Wagenknecht. In the wild party years of the 1980s, The Odeon would stay open until 04.00; it now closes at a more conservative 23.00. It still serves burgers and omelettes but it has also added to its menu more modish fare, from purple sticky rice to vegan options. Wagenknecht’s secret to running a classic? “Simple,” she says. “This has always been the kind of place where we would want to eat.”

theodeonrestaurant.com

Date founded: 1980 (originally opened as Towers Cafeteria in 1932).

Signature dish: Steak frites.

Covers: 120.

Employees: 136.

Known for: Being a reassuring, reliable presence in an ever-evolving corner of Lower Manhattan.

How it has held out: The owner is also the landlord and never succumbs to fleeting fads.

the always-open sandwich spot

Schønnemann

Copenhagen

“Members of our kids’ generation think of themselves as global,” says Juliette Rasmussen. “But it actually means that they value local specialities more.” She and her husband, Thomas, bought Schønnemann in 2015; the classic lunch restaurant in central Copenhagen was founded in 1877 and is celebrated for its open sandwiches, beer and schnapps. “My generation didn’t eat smørrebrød but today’s young people do.”

Between the 1970s and the early 2000s, the cellar restaurant was often at the point of closure. She attributes its renaissance to the New Nordic Cuisine food movement spearheaded by René Redzepi’s restaurant Noma. “He started putting the focus on local food,” she says, while acknowledging the vast difference between the complex fare on Noma’s menu and Schønnemann’s simple, largely unchanging offering. “We Danes went back to our roots. Smørrebrød became trendy again.”

Trendy, perhaps, but part of this restaurant’s charm is that its decor is unaltered by fashion. Rasmussen is proud to employ “real waiters who have time for the guests” but the main attraction is the food: from classic marinated herring to signature dish Madame Schønnemann (calf’s tongue, chicken salad and mustard).

“We aim to have salt, sweet, bitter, umami and sour in every piece,” says Rasmussen. When it comes to smørrebrød, the eternal question is: how many to order? The answer on the Schønnemann website is, “Two is a good base and three should be enough – but with four, you’ll leave with a smile.” It’s advice that has made Danes happy for generations, even as the vaunted Noma announced that it would close at the end of 2024.

restaurantschonnemann.dk

Date founded: 1877.

Signature dish: Madame Schønnemann, which consists of calf’s tongue with chicken salad and mustard on rye, topped with cress.

Covers: 60 across three cellar rooms.

Known for: Smørrebrød and schnapps.

Types of schnapps on the menu: More than 140.

How it has held out: Sticking to its guns.

the city survivor

Sweetings

London

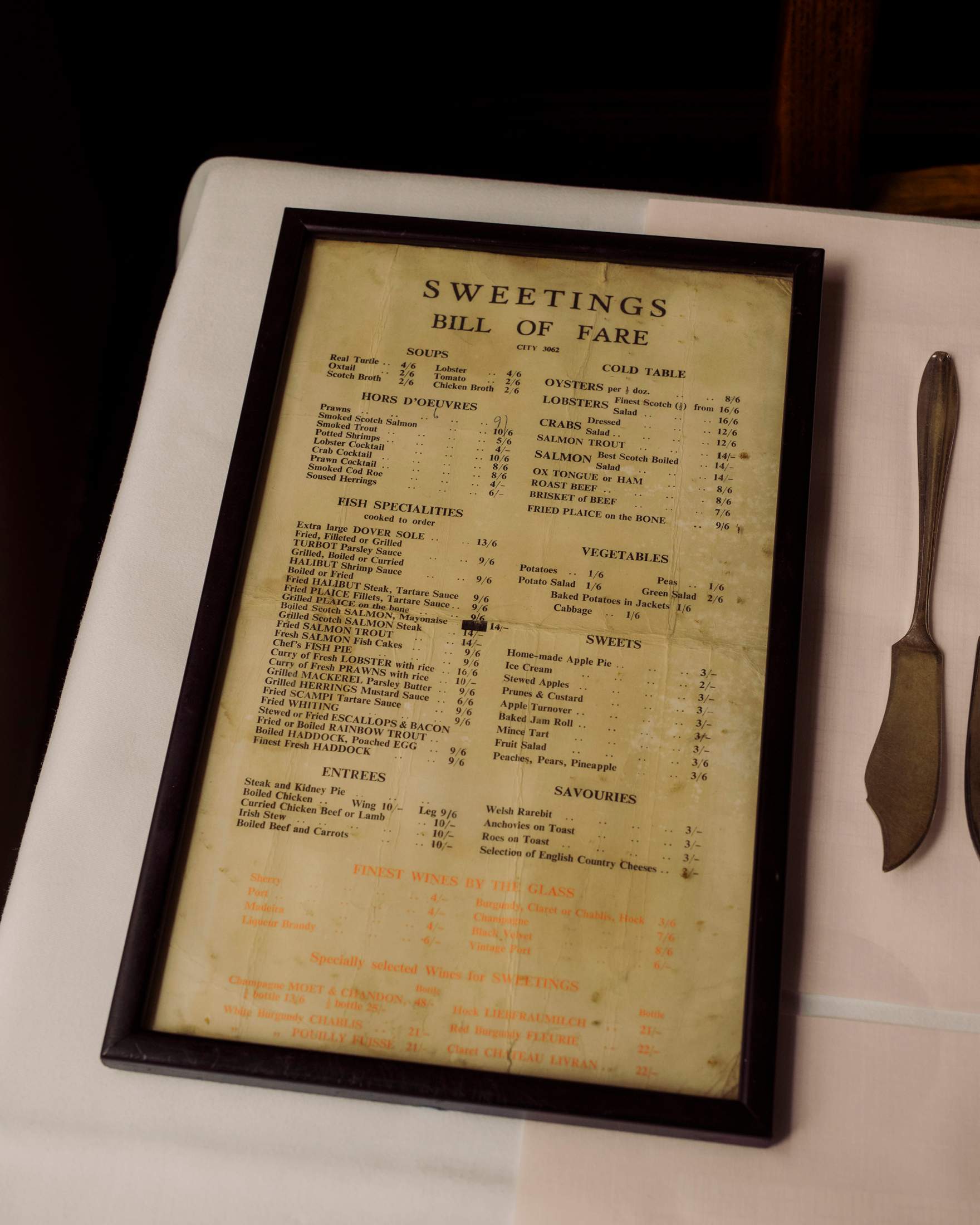

The City of London is a strange, old place where Roman temples sit beneath gleaming skyscrapers. Half a million people descend on the Square Mile every weekday but fewer than 10,000 call it home. As property prices soar across the capital and samey sandwich shops proliferate, it might be hard to fathom how Sweetings, an unassuming 65-cover seafood restaurant founded in 1889, has endured for so long while steadfastly resisting change. You can’t book a table in advance and it doesn’t serve tea or coffee. It’s only open on weekdays and only for lunch (11.30 to 15.00) – the same hours that it kept in the 19th century.

Nevertheless, regulars can’t get enough of this long-unrenovated restaurant, with its wooden wainscotting and nicotine-cream walls offset by linen place settings. Waistcoat-and-tie-clad staff members clip across the terrazzo floor between tables, serving specialities such as the house-cured gravadlax, oysters and Dover sole. When monocle visits, we hear champagne corks popping and the clinking of pewter tankards carrying black velvets (champagne and Guinness), bound for a table of punters in pinstripes. There are private tables for intimate conversations, communal ones for larger gatherings and barstools from which to see and be seen by colleagues – or perhaps adversaries at rival banks. The restaurant’s current owner, Sue Knowler, took over from her father, Dick Barfoot, in 2019. Like Barfoot, Knowler has refrained from changing anything too radically, embracing Sweetings’ unique personality. Long may this understated approach continue.

sweetingsrestaurant.co.uk

Date founded: 1889.

Signature dish: Skate wing with a caper-and-black-butter sauce. Painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was apparently a fan.

Covers: 65 (41 at the bar).

Employees: 11.

Known for: Black velvet cocktails, native oysters and the Dover sole.

How it has held out: It has maintained a strict, almost obstinate adherence to a simple seafood menu and very short opening times. The interior is also an understated masterpiece – cracks, imperfections and all.

Want to spice things up?

Keep an eye out for more hospitality holdouts in forthcoming issues of monocle. And if you’re still hungry for more, tune in to The Menu, Monocle Radio’s dedicated food programme, and subscribe to our weekend newsletters for food scoops delivered straight to your inbox.

monocle.com