Quality of life / Global

Living for the city

Quality of life isn’t just about political solutions. So what else makes a city tick? Our correspondents offer some answers.

1.

architectural adaptations

Fairness and the Empire State

David Bodanis

The race to build the tallest building in New York could have resulted in tragedy, but the Empire State Building made a point of treating its workers well – and won.

The Chrysler Building is the most beautiful skyscraper in New York, all glistening art deco and huge metal gargoyles. It’s the backdrop to many superhero films but, tellingly, when King Kong came to visit the city, he didn’t consider wasting his time there. Who wants to stand atop something merely shiny, when you have military biplanes to bat away, while clutching the love of your life? You need to be bigger and higher. You need, in fact, the Empire State Building – for nearly half a century the tallest skyscraper on the planet.

The Empire State is my favourite tower in the New York skyline – and not just because of its proportions. When it was conceived in the late 1920s, it managed to masterfully balance the notion of quality of life with the needs of the urban environment. It’s a landmark that we should be pondering to this day for that very reason.

The Roaring Twenties were a great time to be rich: the Jazz Age with free-living women in narrow dresses; fast cars and speakeasy saloons; and great new music. For most other people, however, it was rather miserable. There was a rough depression in farming regions and, when unemployed farmers did make it to the cities looking for work, construction foremen knew that there were so many of them (and they were so desperate) that even the lowest wages would be accepted.

The planners behind the Empire State Building took a different approach. What if instead of stiffing their workers as much as they could – paying low wages, taking deductions for random costs and making them go up even on the most dangerous, wind-roaring days – they did the opposite? That meant paying wages at double the going rate and offering quality restaurants on-site as the tower was going up. Plus, no one ever had to go out on exposed beams when the wind was howling – and they would be paid regardless.

Imagine those conditions for a moment. It’s the opposite of many construction sites today, especially in autocratic states looking to turbo-charge “progress”. We know that bragging about how quickly a project is completed in these places is often a sign of workers being exploited. But not when it came to the corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street between 1930 and 1931, even though it went up fast – at one point rising by four-and-a-half floors a week.

It sounds like a fairy tale but that misses the gratitude that good conditions can produce. Everyone – well, almost everyone (this was still New York, after all) – was willing to go the extra mile. Workers, for example, suggested building a miniature railway line to transport bricks into the site, instead of, as was usual before, stacking them on wheelbarrows to be laboriously pushed along wobbling wooden gangplanks. With a peak of 100,000 bricks arriving in every eight-hour shift, that sped up construction a lot. Electricians also spontaneously came up with wired signalling systems to replace the usual bell ropes for announcing when a shipment was coming up.

None of this would have worked if the owners had been completely naïve or simply too idealistic. Without any supervision, hardly anyone is a saint. Foremen would bill for more men than they actually used and tools would disappear. But the Empire State organisers had survived years in New York construction, a life experience which disabuses anyone of belief in the inherent benevolence of humankind. They sent in auditors to clamber through the building twice a day, checking that the workers were where they were supposed to be. Other sets of auditors counted the tools and the materials. The result? Construction was completed in just 13 months.

Despite the benevolent high salaries and excellent working conditions, and despite the street-smart idea to thoroughly check on progress along the way, the building might not have ended up winning the race to be the tallest. When Walter P Chrysler, the Kansas boy who had made a fortune in automotives and wanted to claim domination of the New York skyline, found out how high the Empire State was aiming to be, he decided – in good old capitalist fashion – to cheat. With the workers sworn to secrecy, he had his architect quietly build a 56-metre-tall glass and metal spire. To keep it hidden, workers brought it up through the Chrysler Building in unrecognisable parts and then performed the final assembly inside the empty top floors as the building was still going up. One morning they used hoists to push that spire up through the top of their building. It perched right on top – creating a structure that they were convinced would outdo the Empire State.

Which meant that the Empire State had to cheat right back. Everyone knew the transport technology of the future wasn’t just propeller planes but also lighter-than-air zeppelins. In the late 1920s they were doing a roaring trade carrying wealthy passengers across the Atlantic but the nearest dock was 80km away in New Jersey. What if the Empire State had a new mooring mast stuck on top, something so broad and tall that the Chrysler could never compete with it? A hard build, perhaps – but this is where the committed, grateful workforce came in. Schedules were adjusted, new material was ordered and fresh gantries designed. Walter P Chrysler, a man who hated losing, was forced to give up.

So what lessons can we take away from the Empire State? Cities never stay the same. They’re always changing. Apply the Empire State’s lessons about generosity – sensibly audited generosity, that is – and who knows what can be achieved, from retrofitting for better environmental operation to cleverly converting downtown offices into apartments. We don’t know whether King Kong is ever going to come visiting again. But if he does, what beautiful, humane cityscapes we can create for him to survey. —

About the writer:

Originally from Chicago and now in London, Bodanis is a writer, public speaker and author of The Art of Fairness: The Power of Decency in a World Turned Mean.

2.

the future-proof city

Nusantara: great hope or white elephant?

Joseph Rachman

Later this year, Indonesia will unveil its newest city, Nusantara, a multi-billion-dollar attempt to unite both the country’s sprawling geography and its complex culture.

There’s a construction site on the eastern edge of Borneo in what was once rainforest and is now a giant eucalyptus plantation. Tnes of thousands of workers swarm across its 6,500 hectares dotted with half-finished buildings. The largest is set to take the form of a giant mythical eagle, or garuda, and house the president of Indonesia. An opening ceremony will be held in August, which seems enormously ambitious given the state of incompletion. President Joko Widodo, due to leave office in September, clearly wants his successor to feel unable to abandon the $32bn (€29.3bn) mega-project.

Indonesia’s new capital, Nusantara, is raising the usual eyebrows that tend to dismiss such projects as white elephants. And yet Indonesia is far from the first country to embark on such an endeavour. For sceptics, the motivation is either authoritarian megalomania or utopianism. Kazakhstan’s Astana, for example, is a byword for dictator kitsch featuring monumental pyramids, golden towers and the world’s largest tent. Brasília, meanwhile, is usually invoked as a warning against utopian planning. Oscar Niemeyer’s dream of using architecture to abolish Brazil’s class system collapsed on contact with reality.

For those hoping to spin a similar story about Nusantara, there is plenty to work with. It is billed as a “Smart Forest City” that will regenerate nature, but the reaction from environmentalists has been one of scepticism. The digital command centre that I was proudly shown on my visit, with screens monitoring everything from the location of the site’s earthmovers to social media sentiment about the city, speaks to governmental longing to know and control. Even its name, a Javanese word for the Indonesian archipelago, suggests a certain romanticism over practicality.

Leaders have long seen in new capitals a chance to project symbolic potency. Cosmological principles like geomancy (a sort of geography-based divination) played a role in the founding of ancient capitals such as Kyoto, Xi’an and Kaesong. Earthly authority was bolstered by alignment with the divine order. Even today, the location of Naypyidaw, the new capital established by Myanmar’s military, was supposedly chosen in part due to its astrological significance.

With Nusantara, the symbolic significance of its placement closer to the geographical heart of the country is hard to escape. According to Sofian Sibarani, the architect who designed the city’s masterplan, it will also incorporate the Javanese principle of axially aligning the presidential palace with the mountains and the sea. Nowadays, political legitimacy is imagined to spring not from the divine but the national. This quest to capture the national spirit can lead architects to enter realms of stereotype. Brasília’s architect Niemeyer declared that the city’s design was there to echo “curves found in the mountains of Brazil, in the sinuousness of its rivers, in the waves of the ocean, and on the body of the beloved woman.”

Nusantara carries similar hopes. The style of the buildings synthesises architectural traditions from across Indonesia. The layout, with islands of buildings separated by stretches of green, is supposed to be reminiscent of the Indonesian archipelago. Still, there are reasons to avoid a reflexive sneer, often directed at post-colonial nations. “This strategy is common, not just recently but historically as well,” says Vadim Rossman, the author of a book on capital moves. The projects, he argues, are often more strategically rational than commonly thought. The locations of new capitals often serve practical as well as symbolic purposes, shifting the balance of economic and political power in key regions. Astana helps to defuse ethnic and tribal divisions in Kazakhstan. Brasília develops the Latin American nation’s impoverished inland regions. In Indonesia, geographical balance is a challenge. Tip-to-tip, Indonesia’s 17,000 islands stretch a distance equivalent of London to Tehran. More than 50 per cent of the population live on the island of Java, where Jakarta is found. The idea that relocating the capital to somewhere more central has a logic in a country where politics are marked by resentment about Java-centrism and secessionist movements.

Sometimes, though, the biggest push is simply the unmanageability of the existing capital. Egypt’s plans to move the capital out of Cairo to a new purpose-built city on its outskirts offers escape from not just the traffic of the current capital but also its politically turbulent crowds that brought down the previous Egyptian military regime.

Such calculations might intrude into the desire to escape Jakarta as well. While the current capital’s crowds helped to push the current president to power, they also launched the biggest challenge to his government in 2017 with a series of Islamist rallies against his close ally, the Christian governor Basuki Purnama. Meanwhile, Jakarta’s chaos and the frequency of its flooding is proverbial.

And herein lies the final reason to up sticks and move a capital: physical threat. In the past that meant invading hordes; today that danger is climate-related. Jakarta has sunk nearly five metres over the past 25 years as sea levels rise. Other capitals are also threatened by the weather, with both Bangkok and Dakar vulnerable to sea-level rises. In New Delhi, meanwhile, the heat used to drive colonial rulers to relocate to a summer capital in the Himalayan foothills. With temperatures in central India already turning deadly, a more permanent move could be contemplated.

Capitals are built as visions of a nation’s future – not only as ideals to aspire to, but something projected to last centuries. Nigeria’s Abuja, for example, imagined a post-colonial country that could meet mid-century ideals of modernity conquering nature with concrete, steel and huge roads. Nusantara is the product of a different time, with its designers talking about being not just environmentally sensitive but also resistant to climate shocks. It’s worth contemplating whether Indonesia’s new capital is a vanity project, or simply ahead of the curve. —

About the writer:

Rachman is a British journalist based in Jakarta, covering Indonesia and Southeast Asia. He has written for The Times, Nikkei Asia and Foreign Policy.

3.

refund not defund

Why we should value the police

Gregory Scruggs

Measures to make US police departments more attractive to the general public – not to mention their own officers – are falling short. But there is still hope for law-enforcers.

What happens when someone calls 911? Increasingly in the US, nothing at all. On a recent Saturday night, bass frequencies infiltrated my bedroom. Neighbours were throwing a party into the wee hours on the next block. They were in violation of local noise ordinances, which a municipal website informed me are enforced by the police. I called 911 and a dispatcher transferred me to a non-emergency line. I waited in vain, gave up and put in earplugs.

That Seattle’s finest had no time to respond to a loud party was hardly surprising. By the end of last year, the Seattle Police Department was at its lowest staffing level since 1957 – reaching only about 65 per cent of its own staffing goal. Only the direst emergency calls receive a swift response. Noisy neighbours aren’t going to make the cut.

Seattle’s predicament is hardly unique. Police response times are up nationwide compared to the last decade. The chief culprit for this lag time is straightforward: there are fewer cops to respond to ever more emergency calls. Four years after “defund the police” became a nationwide rallying cry, the aftermath has been disastrous for quality of life in US cities amid a nationwide crime spike that is only now subsiding. Though the dead-end slogan has long been jettisoned by any politician hoping to win a competitive election, the damage has been done. Regardless of how much funding was cut from any given police department, police morale nosedived across the board, even if it was mostly left-leaning elected officials who embraced this political rhetoric at the behest of activists.

Officers quit in droves far faster than academies have been able to train new recruits. Depleted departments now triage casework and focus only on violent crimes, effectively ceasing to police comparatively minor offences such as shoplifting, speeding, graffiti or public drug use. As police enforced fewer crimes, a climate of bold lawlessness flourished. Homicide, other violent-crime and property-crime rates soared in 2021 and 2022. Many cities posted their worst crime statistics since the early 1990s. A look at 2023 and preliminary data from 2024 suggests that most crime has finally begun to lessen – except for car theft, which is rising – as the social unravelling of 2020 has quelled and law enforcement begins to re-establish order. But stubborn outliers remain. Take Dallas, a bright spot in 2022 that saw murders increase last year. Or my city, where shootings are double their frequency prior to 2020.

While Seattle still has a low violent crime rate compared to other large US cities, such comparisons are thin gruel for those who spend summer nights trying to distinguish between the sound of gunfire and fireworks. In the worst-hit cities, this level of violence has hampered urban recovery. In April 2023, Brookings Institution began to publish reports drawn from interviews with business leaders in Chicago, Philadelphia, New York and Seattle. The consensus was clear: the largest barrier for workers returning to downtown offices was public safety. While it’s easy to malign remote workers for an unwillingness to trade pyjamas for professional attire, the sorry state of affairs in many US cities has been that simply going to work can feel like a dicey proposition.

Against this backdrop, city leaders are rightly pursuing “refund” over “defund”. In March the Seattle City Council approved a pay bump that will push starting salaries for police officers to $103,000 (€95,000), among the highest in the country. The hope is that this will compensate for the drawbacks of working in a big city with its higher crime, media scrutiny and sceptical civil society.

But trying to buy their way out of a policing shortage feels short-sighted. What cities really need to accomplish is making the job attractive culturally, not just financially, as it is for so many other fields. Cities must recover civic pride in policing as an institution. Police department leadership needs to instil in the rank and file a sense of how people live and work in cities.

While mayors and council members across the country are singing a much more complimentary tune about the role of police in their cities, there are still pockets of deep resentment in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent civil unrest that shook the nation. The country seems far from ready for a national truth and reconciliation process. But it’s not too late for respected local leaders to convene both cops and activists for mediated conversation to ease tension. It’s past time for social-justice activists to move beyond childish acab (“All cops are bastards”) sloganeering and start engaging in a more adult debate about the role of police in a civil society.

For their part, police working in a big city should start acting like it. Get out of the patrol car and walk the beat. Last summer, Cleveland cops were required to spend at least an hour per shift on foot. This practice should be de rigueur in all the country’s walkable urban areas. Foot patrols will foster more positive interactions.

Better yet, more police should actually live in the communities they serve. Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia all require officers to reside within city limits; in Atlanta and New York’s cases, cops must live within a certain radius. While police unions complain that this regulation is onerous, these cities also boasted five of the 10 highest police-to-population ratios in the US in 2022. Local residency helps officers identify with the city where they work rather than treat it as a faraway job site, or worse, a hostile territory. Who knows, they might even start to sympathise with a neighbour losing sleep over loud music – and perhaps even issue an infraction. —

About the writer:

Scruggs is monocle ’s Seattle correspondent. He has also written for Bloomberg CityLab, Reuters, The Guardian, The New York Times and The Washington Post.

4.

the queen of cities

What we can learn from an ancient marvel

Bettany Hughes

Colourful, cosmopolitan and pioneering in fields of architecture and law – it’s little wonder that sixth-century Constantinople was known as the Greatest City on Earth.

The smell must have hit visitors first: the sultry scent of thick clumps of lavender lining the edges of the royal highway that ran into the heart of the great city. If you rode this processional route, or Mese, from Constantinople’s Golden Gate – built by the Romans and named because it shone with brilliantly polished bronze – you would have been entering the largest and most renowned city on Earth. This metropolis that flourished 1,500 years ago sat between the ancient and modern worlds, between East and West, between the Black Sea to the north and the expanse of the Mediterranean and Egypt to the south across the Sea of Marmara.

Welcome to Constantinople in the year 530. A hub that has had several names during its lifespan, from Byzantium to present-day Istanbul, medieval Constantinople was undoubtedly a golden era, when sobriquets such as the Queen of Cities, the Second Rome or simply the Greatest City on Earth were born.

One of medieval Constantinople’s hallmarks was its verdant, often colourful outdoor areas – the reason that the city brought so much joy to its residents. That previously mentioned central highway, for example, was once lined with vegetable patches, even if today you would be hard pressed to imagine it, wandering around what is now a glitzy shopping street.

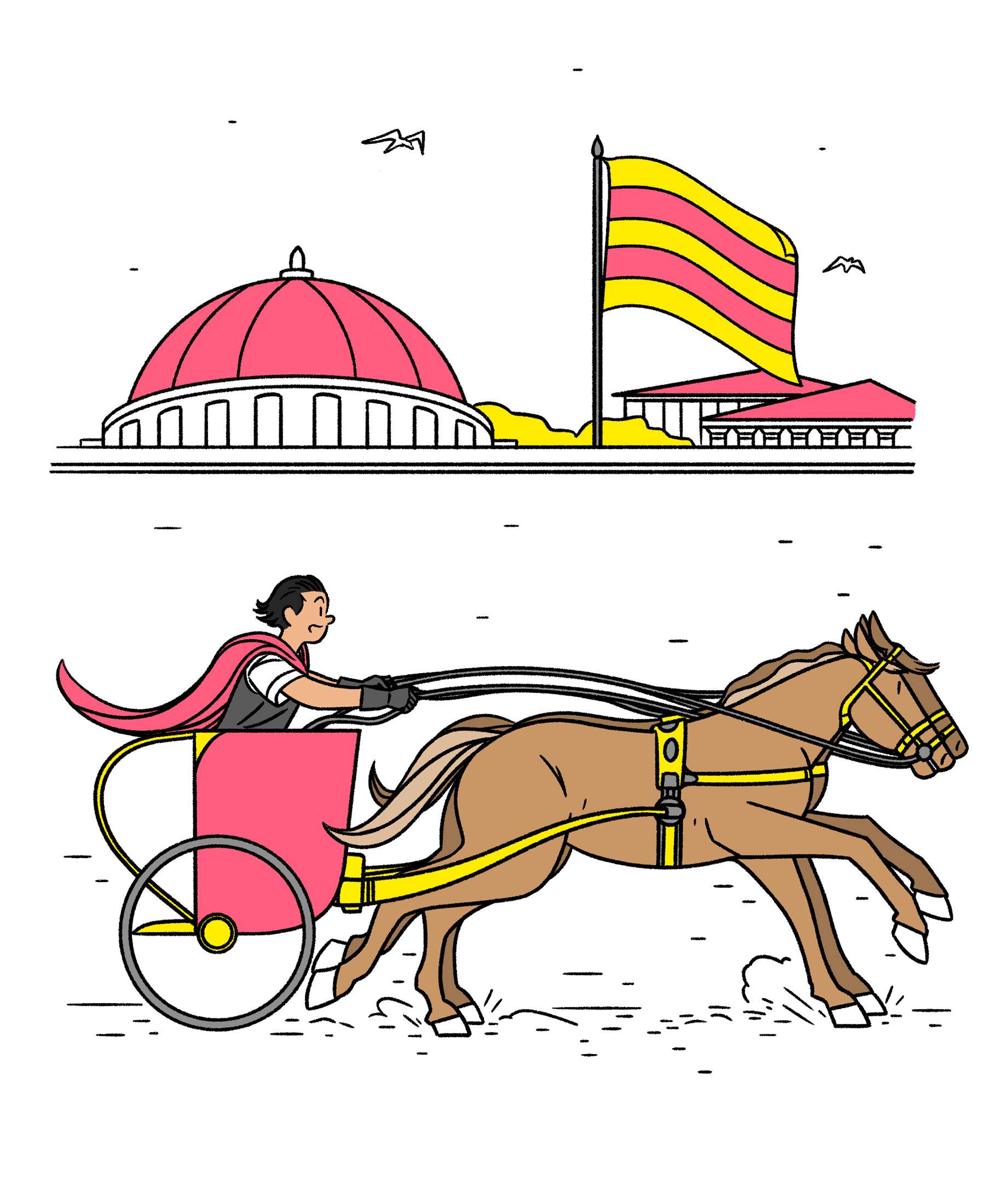

Neighbourhoods of the city were colour-coded according to people’s allegiances to chariot-racing teams, with ardent fans faithful to the Reds, the Whites, the Blues or the Greens – passions as fierce as any modern- day football supporters. But the colours didn’t stop there. Special courtiers would sometimes wear red buskin boots and the imperial palace was draped in purple silks, while purple-stone bed chambers inside reflected the royal colour.

The rulers of Constantinople were also pretty extraordinary. Emperor Justinian had originally arrived in the city from rural Illyria (near modern-day Macedonia) and hailed from a family of peasant swineherds. Tearing his way up through the ranks of the imperial bodyguard, he shocked stuffy senators and aristocrats by changing the law so that an emperor could marry an “actress”. Justinian’s fiancée was the remarkable Theodora – a young woman who, we are told, started life as an erotic dancer, the daughter of a bear baiter and a sex worker. Humble origins would not stop these ferocious pioneers. By the end of his life, Emperor Justinian and his beloved Empress Theodora reigned over some two million square kilometres of territory, spanning Europe, Asia and Africa.

The couple set about proving that their second Rome could be every bit as sensational as the first, turning the city into a hotbed of ambition and ideas. The ruling duo reconstructed the great church of Hagia Sophia, complete with a dome that would be the largest on Earth for 1,000 years. A system of sanctuaries and safe houses for refugees and abused women was established.

The pair also set in train a legal code that outlawed infanticide and increased penalties for rape, enshrining the principle of innocent until proven guilty – still the bedrock of most of the world’s legal systems. Meanwhile, their propaganda merchants were sent out to burnish Constantinople’s reputation as a radical new centre of social justice as far afield as Yemen, India, Lower Nubia and even Cornwall, with Justinian distributing subsidies “to the barbarians of Bretannia”.

Constantinople in the sixth century was the city for which the phrase cosmopolitan could have been invented. Physically and psychologically, all points of the compass counted. Those lucky enough to live here at that time could truly describe themselves as citizens of the world. —

About the writer:

Hughes is an award-winning historian, author and documentary maker. She is the author of several books, including Istanbul: A Tale ofThree Cities.

5.

night owls

How the Spanish stay young

Francheska Melendez

The Spanish can proudly boast of their longevity but why do the country’s elderly citizens thrive so well in their later years? Perhaps it’s because they like to party…

Little did I know when I moved to Madrid that it would be the country’s senior citizens who would teach me how to handle myself on nights out. Though I hail from New York, the city that never sleeps, it was in Spain that I learned how incandescent the early morning hours can be. One night at a piano bar, I gazed in admiration as an octogenarian diva passionately sang “La Zarzamora”, a cautionary tale written in 1946 about giving one’s heart to a married man. It was 03.00.

That singer was part of a glittering set of night owls, all over 50, who performed at the piano every night. Yet Spain’s senior citizens’ embrace of the nighttime economy hasn’t hurt their longevity; I’d vouch that it’s part of the reason for it. In 2022 the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs projected that, by 2065, Spain will rank as Europe’s top for average life expectancy behind Japan and South Korea: 92.7 years.

Spaniards cite the Mediterranean diet. But there is something more subtle at work in the sparkling eyes of Spain’s yayos, technically meaning “grandparents” but often an affectionate moniker. While in some other countries, members of older generations are expected to retreat from social life, the opposite is true in Spain.

The world’s longest-running study on longevity, the Harvard Study of Adult Development, found that, often, those who thrive in their golden years have fostered relationships that make them happy. This tracks with what can be seen on any summer evening along the Iberian coast: yayos dressed to the nines out on a stroll, having a laugh, maybe even going for a dance.

Last spring in Seville during La Feria de Abril fiesta, Rocío Tayan, a woman in her eighties, who I had never met before, laid eyes on me as I sang to the music in her pop-up party tent. She made a beeline for me, a bottle of champagne in hand, so we could share a toast. Another yaya teaching me how to handle myself on a night out. —

About the writer:

Originally from New York, Melendez covers Spain for monocle and Konfekt. The country has furnished her with a passion for belting out jazz standards.