Fashion: Bally / Switzerland

Crafted with care

Since becoming Bally’s creative director in 2023, Simone Bellotti has been on a mission to bring Swiss precision and craft into our closets.

Picture Switzerland and you’ll think of high-end watches, artisanal chocolate, world-class financial services and the Alps. Luxury fashion, however, hasn’t traditionally been on that list. That was particularly true in recent years, as the country’s flagship fashion label, Bally, navigated choppy waters. The 173-year-old brand had been in a state of flux while its owner, German conglomerate jab, looked for a new buyer. In May 2023, however, Italian designer Simone Bellotti took over as design director and the label has swiftly turned things around. It was one of the most lauded labels at this year’s Milan Fashion Week, found a new backer in US investment firm Regent and now has the opportunity to turn over a new leaf.

Bellotti, who joined Bally from Gucci, worked quickly and with conviction, returning the label to its Swiss roots and defining a new Mitteleuropean silhouette along the way. In his hands, Switzerland’s well-rehearsed tropes have been worked into chic wardrobe staples, piquing the interest of international retailers including Luisaviaroma and Net-a-Porter, which began investing in the brand for the first time. “Bellotti has asserted a new vision for the brand that is synonymous with Bally’s heritage,” says Katie Benson, buying director at Net-a-Porter. “We expect him to move from strength to strength, with his ability to balance fashion and function.”

By achieving this delicate balance and staying focused on the company’s roots, the designer has been able to command the attention of fashion critics and consumers alike – something that his predecessors, who had been caught in the trap of jumping on trends and resorting to the conventional marketing playbook, repeatedly failed to do. “Bally’s leather pieces, Mary Jane shoes, jackets featuring new proportions and oversized men’s totes are now filling our wardrobes,” says Marta Gramaccioni, buying director at Florentine retailer Luisaviaroma, another new partner.

Behind the scenes, the Bally team, which is now split between Milan and Caslano, is rejoicing after years of uncertainty. In 2020 a sale to Chinese textile group Shandong Ruyi fell apart in public, as did an earlier attempt to get the business back on track by hiring Los Angeles-based Rhuigi Villaseñor, founder of streetwear label Rhude. Villaseñor’s strategy for reviving Bally – riffing on streetwear, celebrity culture and 1990s fashion – was at odds with a brand built on family values, pragmatism and the craft of shoemaking. Unsurprisingly, the collaboration ended after two seasons.

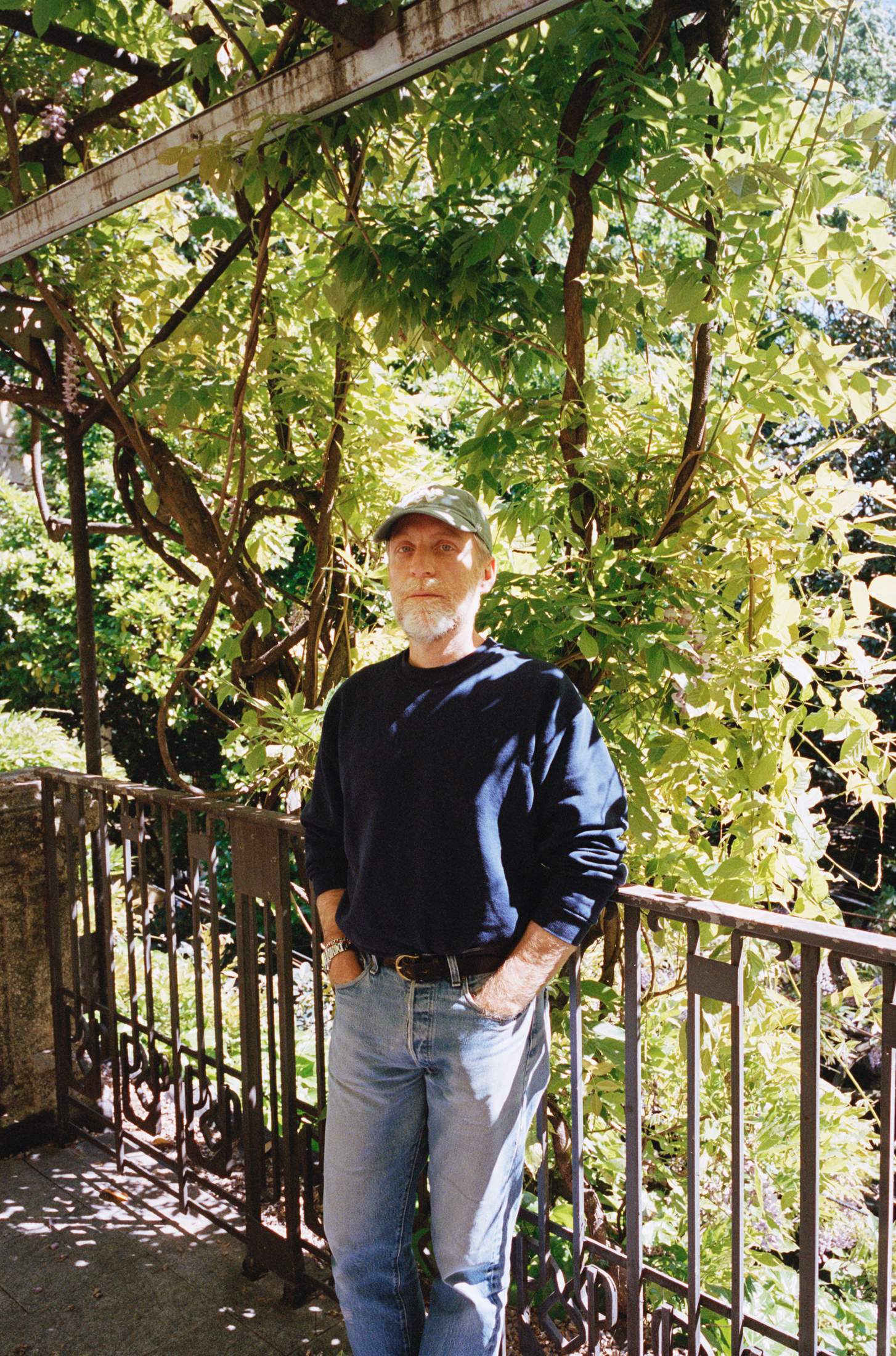

Bellotti’s vision is starkly different. “I wanted to play with clichés,” he tells monocle, while walking through Bally’s showroom in a prime corner of Milan’s Porta Venezia. He picks up one of the biggest hits from his debut collection: the Bally Belle, a handbag structured in thick leather to evoke the shape of a cowbell. It’s the clearest example of Bellotti’s playful rummage through the brand’s history and wider Helvetian culture. The collection hanging in the cavernous showroom, a former cinema, gives a first impression of cool composure, with wool coats in army green and preppy polo shirts stitched with the Bally family crest. But upon closer inspection, you’ll spot lace-up work boots and leather skirts studded with tiny shepherds and edelweiss.

Another hit is a pair of Mary Janes, a flapper-era strapped shoe that has enjoyed a surge in popularity this year. Its basic design has been in the label’s archives since 1923; Bellotti simply updated it. “Any style of shoe that you can imagine, Bally has already done it,” says the designer, who has developed an encyclopaedic knowledge of Swiss history. He cites Monte Verità, an early-20th-century commune of artists and intellectuals on the shores of Lake Maggiore, as a source of inspiration. He has also introduced the Ballyrina, a dainty shoe stamped on the sole with the image of a dancer, with the word Bally forming the shape of the tutu. The logo is also an archival find that dates back to the 1940s, when wartime import restrictions prompted the company to offer Swiss-made dancing shoes.

Focusing on footwear is a smart move, not only because it’s one of the most appealing categories for entry-level buyers but also because it’s at the heart of Bally’s history. The brand was founded in 1851 in the village of Schönenwerd by Carl Franz Bally, a ribbon manufacturer who was inspired to pivot to shoemaking after a trip to Paris. Carl Franz was a keen businessman. The company started expanding internationally as early as the 1920s, turning Schönenwerd into an industrial hub. From its founding until 2000, Bally produced more than 150 million pairs of shoes.

The brand has always riffed on its Swiss heritage. Its signature handbags and trainers usually feature a red-and-white cotton stripe that nods to the company’s origins as a ribbon-weaving factory. The trend in the wider industry of abandoning traditions, redesigning logos and switching out staff is a relatively recent phenomenon, the result of a feverish game of musical chairs between fashion houses and creative directors. But that has never appealed to Bellotti. Instead, he wanted to immerse himself in Bally’s vast archives.

The Ballyana Museum in Schönenwerd stores every shoe model that Bally has made since 1851 and, in true Swiss form, they’re all meticulously preserved and catalogued. “There’s a whole world inside,” says Bellotti. “You can see the evolution of dressing and of society at large.” The Bally family has also amassed a museum-grade shoe collection from across the globe that rivals that of any big luxury house. Bellotti has spent a lot of time here opening boxes containing Inuit shoes or ancient Roman sandals. “Of course, you have so many ideas when you’re lucky enough to be working with such an archive,” he says.

Inspired by his discoveries, he has continued to print red-and-white stripes on Bally’s leather handbags, including a popular series of satchels, while tags with the family crest are proudly sewn on the sleeves of blazers and knits. His autumn-winter 2024 collection, titled Der Wanderer, was inspired by Engadin folk myths about a double-tailed siren that lures fishermen to drown in icy lakes. Also on Bellotti’s mood board were Appenzeller folk costumes that disguise people as trees, as well as portraits of Zürich’s 1960s rebel youth. The references inform his collections in subtle and often humorous ways, from the Fair Isle patterns fashioned into a pair of knitted shorts to the subtle flaring of the hem of a winter frock.

Bellotti says that brands should be built like personalities. “There’s the more serious part of us that helps us to make sensible decisions in life,” he says. “But nobody wants to be serious all of the time. But we also have a more irrational side.” He credits this philosophy to his time working with former Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele, who also succeeded in turning around the fortunes of a heritage brand – a luxury house that was founded, as Bellotti points out, 70 years after Bally. “You can create anything with your imagination,” he says. “What emerges is an inner world.”

In fashion, convincingly capturing that world is like hitting the jackpot. Bellotti seems to be well on his way to accomplishing this. The investment from Regent and the expected appointment of a new ceo (Nicolas Girotto, who helmed the label since 2019, stepped down in September, shortly after the acquisition) will give him an even bigger boost and allow him the luxury of time when it comes to executing his turnaround strategy. Despite the warm reception to Bellotti’s collections, Bally has not embarked on a marketing blitz. Meanwhile, the brand has flagship shops in Milan, London and New York from before Bellotti’s time but, so far, he has made no effort to overhaul them. “Bellotti and Regent are paving a clear relaunch strategy, sharpening Bally’s brand image and product offering,” says Mario Ortelli, managing partner of the luxury advisory m&a firm Ortelli & Co. “Once those areas of the business are developed, they will also be able to work on distribution and translate the progress that they have been making into higher revenues and margins.”

The creative director is clearly having fun. In the showroom, he picks up the Scribe, one of Bally’s more classic styles. Max Bally, a grandson of Carl Franz, designed the slim men’s dress shoe in 1951 to celebrate the brand’s centenary. Most shoes are made in Caslano in a process that involves more than 200 steps from start to finish. That level of craft can even surprise a high-fashion veteran such as Bellotti. “The stitches are perfect,” he says, looking closely at the pinpricks of thread that hold the leather in place. “Very few factories can still make shoes this well.” The only adjustment that Bellotti has made is to widen the toes by a few millimetres.

“Can you guess what this is?” he asks, pointing to the tip of the shoe. Here, the outer edge of the sole is curved slightly inwards. Barely half a centimetre thick, the concave detail could easily go unnoticed. Bellotti explains that the feature, called the double lambris, is designed to function as a tiny rain guard that directs water away from the leather of the shoe in wet weather. Despite a 23-year career spent at Europe’s top fashion houses, Bellotti had never come across such intricate functional details until he arrived at Bally. “I’m learning things,” he says.

Bally’s collections are produced with the same precision and know-how as watches in Le Brassus or chocolates in Vevey. “They know how to make things well,” says Bellotti. “That has been the constant over all of these years.” Everyone knows what Swiss quality means. Bellotti is just bringing this into our closets. — bally.com