Essays: Global views / Global

Points of view

Critical thinking, expert insights and bold opinions on cities, espionage, diplomacy and more, from experts in their respective fields.

The latest instalment of our new essay section touches down in Lebanon, the US, Denmark and more. From food allergies to urban ills, via a deep dive into international peace mediation, the nine essays which follow are here to teach you a thing or two – even how to carry out an art heist. They will also tempt you to pause and ponder. Have you ever, for example, contemplated the poignant and moving links between war and poetry? We do here.

As ever, we’re not shy of getting stuck into an argument or going against accepted wisdom. Ever wondered why there aren’t more female spies on the pages of our novels? Should Germany rearm? Are cities bad for us? The answers proffered here might surprise you. —

urbanism

Cities are bad for us. Let’s fix them

Rasmus Astrup

Cities can be inspiring places that bring out the best in us. But they’re often concrete jungles that make us ill and are still designed around the automobile. What if they were places in which you could thrive rather than simply survive? Another model is possible, according to one Danish designer.

Like many Danes of my generation, much of my childhood was spent immersed in the world of Lego. The “City” universe was my absolute favourite. I got to play the role of urban god, carefully piecing together my dream metropolis from the ground up. I had a fire station and an assortment of other buildings but most of my constructions came from my imagination. Gardens were essential, with tiny flowers and soft plastic trees filling the spaces between my buildings. Even back then, I was obsessed with trees – both in my Lego world and the real one.

What I didn’t realise at the time was how much the layout of my pretend city – like so many real ones – was governed by roads. The foundation was always a grid of grey plates directing the flow of traffic and determining how everything else would fit together. If the roads didn’t connect seamlessly, the city simply wouldn’t work. They dictated everything. That’s how I formed my earliest, unconscious definition of a “real city”.

A few decades have passed since then and I now spend most of my time, in my work as an urban designer, rethinking and challenging what a real city could and should be. Despite all the energy and creativity they hold, urban environments are also responsible for making us sick. They pollute the air with heavy metals, trap heat in concrete jungles and surround us with so much noise that our brains and hearts struggle to find peace. Despite being home to much of the world’s population, cities often isolate us more than they connect us.

Let me be clear about one thing: I love cities. I grew up in Copenhagen, and today I live in the heart of the city with my family, right next to a busy road. I thrive on the energy that cities provide – the inspiration, the communities, the culture and the innovation. Cities are where ideas take root and where diverse people come together to create something greater than the sum of their parts. I want my children to experience this richness of life, which is why we’ve chosen to stay in the urban core. But there are aspects I don’t love: the unrelenting traffic just outside our door and the sheer amount of space dominated by black asphalt, covering about 80 per cent of the public area between buildings where I live.

That’s why I began to construct my own little slice of urban life – my garden. When we bought the house, this garden seemed like no more than a parking space. But slowly it evolved into a green oasis. My goal was to create a haven for my family; a place where we could escape the noise and heat of the city. We planted as many trees as we could afford, transforming the area into a biodiversity hub, providing shade, lowering temperatures and absorbing rainwater. More importantly, we created a sanctuary filled with birds whose songs drown out the cacophony of urban life (city birds sing louder than their rural counterparts; nature’s own way of adapting to urban noise). Our garden isn’t just about greenery, though. We also installed a noise-reducing fence made from poplar bark, a sustainable by-product of the furniture industry. The bark absorbs airborne pollutants from car exhausts, which improves air quality around our home and provides a natural, tactile material that passers-by can’t help but touch.

The poplar fence panels came from an exhibition by sla – the studio where I’m design principal – at Copenhagen’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Our exhibition focused on the power of trees and nature in cities. Our fence, like trees, represents a small but effective act of resistance against the problems that urban life can create. Noise pollution, in particular, is a silent killer. It causes stress, disturbs our sleep and contributes to chronic health issues. The simple act of planting trees and installing noise-reducing materials can transform a space and dramatically improve our quality of life. Cities should not be places where we merely survive; they should be places that we truly love.

At the heart of all my work is a desire to improve quality of life – for all life. Our team includes biologists, architects, landscape architects, planners, lighting designers and anthropologists, working together to design cities that don’t just look beautiful but function in a way that makes life better for everyone. We’re also challenging the traditional hierarchy of cities, where roads and cars have always taken precedence. We’re not advocating for their removal but we believe that it’s time they stop ruling the urban landscape. City design needs to change urgently.

One of the most eye-opening experiences I’ve had was working closely with indigenous designers in Canada, whose traditional knowledge, stretching back thousands of years, offers an invaluable perspective. Their principle of considering how every decision will affect the next seven generations forces us to think beyond the short-termism that dominates most modern urban planning. How many recent developments in the city where you live have been designed for two generations after you, let alone seven?

One specific conversation with an indigenous designer left a lasting impression. We were discussing the rather technical term “storm-water management” when he interrupted to suggest we just call it “rain” or “the flow of water that falls from the sky”. This simple reframing, from technical to nature-based, shifted my perspective. Everything in nature is about flow, he reminded me: wind, water, energy, even people. Yet for the past century or so our cities have been built to disrupt these flows. This is why Copenhagen was hit so hard by flooding in 2011 (my own basement was one of thousands filled with water). And now even desert cities such as Dubai, which once laughed off our rainwater-management proposals, are asking for help as they face big water challenges of their own.

Unfortunately, meaningful change in cities only seems to happen when insurance companies and municipalities are forced to act after suffering massive financial losses. But you can’t put a price tag on quality of life. Feeling safe, connected and good are invaluable concepts. Cities should be designed to provide them.

Planting trees is perhaps the simplest and most effective way to improve urban life. Trees change not only the physical environment but also the way people feel and behave in public spaces. Think about where you would rather spend your day – in a park under a tree or in an asphalt car park under a lamppost? Nature has been proven to lower stress levels, make people feel more at ease and encourage social interaction. When we feel connected to nature, we feel more connected to ourselves and to others.

My best memory of this is our collaboration with 1,500 Copenhagen students, helping them to transform their 1960s concrete outdoor space into a social and biological corridor. The composition of their dorm was changed to include 10 per cent set aside for socially disadvantaged individuals. The students took clear social responsibility by inviting their less fortunate peers into their home. They intuitively understood the connection between biological diversity and social equity.

The path forward may be challenging but it’s exciting. We can change the way cities are built and experienced. As someone who started life literally playing with the concept of how a city should look, I now find myself working on how to grow them, for us and for future generations. Cities are often bad for us – but it doesn’t have to be that way.

About the writer

Astrup is partner and design principal at Danish studio sla, specialising in city nature, sustainable landscape architecture and integrated climate adaptation. He spoke at The Monocle Quality of Life Conference in Istanbul in 2024.

culture

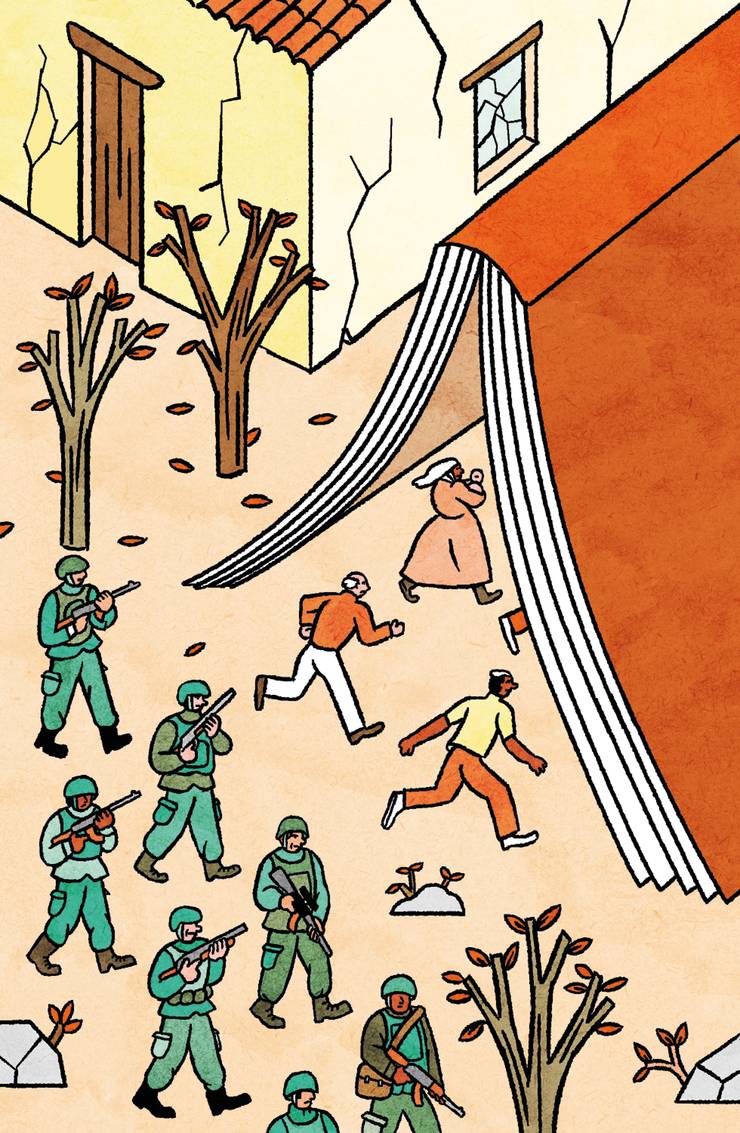

War and poetry

Lindsey Hilsum

We can be overwhelmed by the words and images filed from conflict zones. And while they give a comprehensive account of a situation on the ground, sometimes the language fails. Which is where poetry comes in. Over the years, this journalist has found solace in the form, which conveys the experience in ways that the news cannot.

One Saturday last October, as we entered an elegant restaurant in downtown Beirut for lunch, my Lebanese colleague pointed out a Hezbollah minister sitting smoking shisha. He was a slim man in his early fifties, wearing a grey baseball cap and, like the other three men at the table with him, black jeans and a black T-shirt. We stopped to talk; Israel’s war against Hezbollah was at its height, with daily bombings of targets across the country. After we got to our table we laughed, slightly nervously, about whether the Israeli drone whirring overhead would drop its bomb before or after we had eaten our main course.

Black humour is a staple of life in places such as Lebanon, where your destiny seems to be beyond your control. The same Lebanese colleague had been late that morning because she was stuck in a traffic jam; the Israelis had bombed a car on the road ahead, killing two people inside. I never did find out who. A Hezbollah commander and his wife? A visiting Iranian financier? It could have been either. You couldn’t know whether the person in the car you were passing, or in the house next door, or on the street as you walked by, might be a target.

Poetry is another way that people survive the fear and uncertainty that war brings. Four lines by Bertolt Brecht have become an aphorism:

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing

About the dark times.

After living through the civil war in the 1970s and 1980s, four Israeli invasions, numerous assassinations of leaders, economic collapse and, in 2020, an accidental explosion of nitrates at the Beirut port, which has been described as the most powerful non-nuclear explosion in history, Lebanese people are fed up with being praised for their resilience. A poem by the New Orleans poet Zandashé l’Orelia Brown that starts, “I dream of never being called resilient again in my life/I’m exhausted by strength”, has been circulating on social media. It resonates across borders and cultures.

People often turn to poetry in times of personal grief and trauma, as well as political crisis. This is why, in my career as a reporter often covering conflict, I have always carried a volume of poetry with me. Poetry has an allusive power that journalism lacks; it picks up where we leave off. I turn to it when my own words run out.

Though the TV images we see daily have a huge effect, journalistic language sometimes fails to convey the intensity of the experience. As journalists we pride ourselves on the clarity of our prose and on making complex stories simple. Our job is to explain why terrible things are happening and to challenge the euphemisms used by politicians and military spokespeople. We also try to convey the thoughts and feelings of those we meet and a sense of what it feels like to be on the ground. Yet we may lose the deeper meaning, such as the universal significance of what we have witnessed or the contradictory emotions that war engenders.

On 21 October, Israel bombed, without warning, a building next to the Rafik Hariri hospital, the biggest health facility in Lebanon. Eighteen people were killed. We arrived the following morning to see a bulldozer scraping away at the wreckage. It would stop and the watching crowd would fall silent so that people could listen in case any mobile phones were ringing from inside the mountain of rubble. A man in a red baseball cap with tattooed arms scrambled up and started desperately digging with his bare hands. He was looking for his five-year-old son, Ali. Reaching into the crumbled ruins of his house, Ali’s father pulled out a multicoloured sack. He turned it upside down and a stream of plastic toys poured out, their bright pink, yellow, red and blue stark against the grey ruined concrete. “Are these the Hezbollah weapons?” he shouted. I thought of Anna Akhmatova’s poem about the siege of Leningrad, in which she compares the sound of a bomber to thunder that doesn’t bring blessed rain:

My distraught perception refused

to believe it, because of the insane

suddenness with which it sounded, swelled and hit,

and how casually it came

to murder my child

The shock of the last line echoed the shock I felt in the moment, watching the unspeakable pain of a father who has lost his own.

The dominance of the Great War soldier-poets – Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg – in Western culture might lead to the assumption that war poetry is a male preserve, and that Western poets have a monopoly on the form. This is far from the case. The first known war poet was a Sumerian high priestess, Enheduanna, who lived in Ur, in what is now southern Iraq, in about 2,300bce. Contemporary poetry, much of it written by women, reflects the fact that modern conflicts tend to kill more civilians than soldiers. The late Irish musician Frank Harte said, “Those in power write the history; those who suffer write the songs.” A lot of songs and poems have been written in recent years.

Across the Arab world, poets are revered. Poetry is not seen as an elite pastime but central to culture and identity. Poets may be as important as soldiers in other conflicts too. A statue of Taras Shevchenko, with his massive, drooping moustache, stands in nearly every town I have visited in Ukraine. The reputation of the national poet, who wrote revolutionary verse in the 19th century, has been further elevated by the 2022 Russian invasion. In Borodyanka, a small town near the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, which saw some of the worst of the early fighting, he surveys a bombed-out apartment block, the windows blackened and broken.

More than 150 years on, his struggle is not yet won. A new generation of Ukrainian poets has been born of the war, writing in Ukrainian not Russian, part of an assertion of Ukrainian culture. Focusing on physical suffering, Western journalists may fail to see the importance of art to people struggling to preserve their humanity. Mental health and trauma are a focus but we are often oblivious to spiritual and religious needs, and to the yearning for the comfort of ritual and recitation that poetry provides.

That yearning is increased when people are forced to flee. Refugees bring only what they can carry, which often means songs, stories, poems and prayers that they know by heart. They can’t go back, not just because it’s dangerous but because the country they grew up in no longer exists – war changes everything. They are lost in both space and time. Verses learnt on a grandmother’s knee or in school are anchors to the old life and provide a source of strength and identity that give solace in an alien and often hostile world. In TS Eliot’s words from “The Waste Land”: “these fragments I have shored against my ruins”.

While we ate our lunch in Beirut, the minister’s driver leant against his black four-wheel-drive with its tinted windows, smoking and looking up at the drone, before finishing and whisking his boss away. A few minutes later a new party arrived at the table. They couldn’t have been more different: four fashionably dressed women with bee-stung Botox lips and sunglasses perched on their head. The two divergent sets of table guests are part of the complexity of contemporary Lebanon, land of chuddars and bikinis, political parties with their own militia, and multiple sects and religions. Even in the darkest of times, it’s possible to admire the glory of Lebanon’s contradictions and diversity.

As the great Lebanese-American poet Khalil Gibran wrote in the 1920s:

You have your Lebanon and its dilemma

I have my Lebanon and its beauty

Your Lebanon is an area for men from the West and men from the East

My Lebanon is a flock of birds fluttering in the early morning as shepherds lead their sheep into the meadow and rising in the evening as farmers return from their fields and vineyards

You have your Lebanon and its people

I have my Lebanon and its people

Poets don’t have the answers but they can turn the horror of war into works of beauty. Journalism is of the moment; poetry lasts forever.

About the writer

Hilsum is international editor at Channel 4 News in the UK. Her new book, I Brought the War with Me: Stories and Poems from the Front Line, is published by Chatto & Windus.

food and drink

Learning to be tolerant of food intolerance

Tim Hayward

A large and increasing number of people now identify as sufferers of food allergies and intolerances (diagnosed and otherwise). But what’s the recipe for catering to those who might be simply picky and neurotic? A restaurateur sets the table for success.

It’s pretty rare, as a restaurant critic, that I become immersed in the niceties of theological debate – but that’s the rabbit hole in which I found myself recently. At an Anglican Eucharist service in Cambridge, I heard the priest issue a warning from the pulpit that anyone intolerant to gluten should not step forward to receive the host.

Some of the greatest schisms in the church have developed around the complexities of transubstantiation – whether, at what point and how the blessed bread and wine transform into the actual body and blood of Christ. There is a gigantic quantity of writing about the practical details. I willingly plunged in to find out.

The Church teaches that to be valid, the Eucharist “must be offered with bread and with wine in which a little water must be mixed”. The Code of Canon Law specifies that bread “must be only wheat, and recently made so that there is no danger of spoiling”. So can you have a “gluten-free host”? Not if it’s made solely from wheat, as prescribed. And so, faced with the awful possibility of having to opine on whether the flesh of the son of God, at the point of transubstantiation, is fully gluten-free, Canon Law has stuck with the marginally less controversial ruling that coeliacs shouldn’t take communion. My point? If you think religious law is confused, take a look at the hospitality sector.

As well as writing about food, I run a café and bakery. In common with many of my colleagues in the hospitality industry, we handled the food-intolerance issue badly at first. We were baffled, incredulous and often angry when a vast surge of allergies and sensitivities presented themselves in our dining rooms. When the hell did everyone start thinking that a bakery was a good place to expect gluten-free food? Nut allergies and anaphylaxis, we could handle, we were trained. Besides, we reasoned to ourselves, people with EpiPens had always known how to handle themselves. But this new stuff was uncharted territory.

And then the law changed. Governments across Europe began legislating for product labelling and new service behaviours across the food industry to meet the problem. The costs of complying were astronomical, the cost of failure unimaginable. For a while, the genuine rage in the industry was palpable. We knew that allergies were a serious issue; they always had been. But now law was being written pandering to the worried, the neurotic and the self-diagnosers. Ask any front-of-house staff and even today they’ll have 100 war stories of customers ordering an egg-white omelette “with no egg” or finishing a diligently prepared gluten-free meal by spontaneously diving into the chocolate cake. And it’s not just a few tales retold; every single person working in hospitality had regular experience of customers “crying wolf”. Then things changed again.

It’s difficult to pinpoint any exact moment. Certainly, as the numbers increased, everyone knew people with intolerances or allergies personally. Allergies and intolerances affected everyone. In supermarkets and food manufacturing, the changes in labelling progressed. You couldn’t miss the aisles of “free-from” food and the increasingly detailed labels wherever you shopped. But hospitality required more nuanced changes in attitudes and behaviour.

Today, the question arrives right at the top of the order of service: “Does anyone at the table have any allergies we should know about? Let me get you some menus.” Your preferences are carefully noted and acted on. Restaurants now talk about “dietaries” in the same way they talk about wine preferences or whether a customer is a decent tipper. There’s no more judgement of an individual customer avoiding hot spices or members of the nightshade family than there would be of avoiding peanuts or pork. We’re geared up for it now, and whether your preference reflects millennia of your culture or something you heard last week from a very thin person on Tiktok – be it a diagnosed medical condition or a complete whim – it’s nobody’s damn business but yours as an individual.

Is this a sign that the hospitality industry has grown up a bit? Well, yes, but customers have changed too. High-maintenance punters still delight in giving staff the run-around with complicated requirements but there have always been people like that. Before they realised that they could request “nothing red on the plate”, they would have been complaining about the noise of the air-conditioning, the proximity of the bathroom or deploring the placement of a side plate. They’ll always be with us. Meanwhile, the eternally fretful “picky eaters” have moved on to part-time veganism, fear of carbohydrates or plant-based dietary demands. There’s still a long way to go but, importantly, a more mutual trust has grown and people with genuine allergies or intolerances are beginning to feel heard.

Perhaps the best indicator of this is the presence on menus, along with a slew of “free-from” options, of the ubiquitous quiet announcement, “While we try to ensure that our products are made without allergens, they may be used in our kitchens. Please ask your server for details.” This isn’t a disclaimer; it’s a discreet invitation to talk. You want to see exactly what allergens are in every dish on the menu, sure. We have a stack of spreadsheets as thick as a loaf of bread. But we can sort this out a lot more comfortably with a 30-second chat, at the end of which everyone feels heard, understood and, above all, safe.

There’s a model in psychoanalytic theory called Transactional Analysis, which posits that both sides in a relationship will occupy one of the three “ego states”: parent, adult or child. If one participant acts like a child, the other is inclined to, or sometimes forced into, acting like a parent, and vice versa. In therapy, the aim is to achieve a simple equilibrium, a grown-up state where I, as an adult, speak to you, also an adult.

For a long time, the hospitality industry, shocked by the pace and manner of change, behaved like children, refusing to take responsibility for the food we served, forcing the customers to do all the grown-up thinking. Sometimes, customers behaved like children, expecting the industry to cater automatically to their every imagined need, forcing us to take control and responsibility.

Today it feels as though we might finally be communicating, talking about a shared responsibility like adults. It’s a more relaxed and hospitable state of affairs. We care about you as guests; you trust us as hosts. It’s how it was always supposed to be. And that should have our blessings.

About the writer

Hayward is an award-winning British writer, broadcaster, restaurateur and “unrepentant food geek”. His latest book, Steak: The Whole Story, was published in 2024 by Quadrille.

culture

How to stage an art heist

Orlando Whitfield

What would happen if your friend and one-time business partner was behind the biggest art fraud in US history? It happened to author Orlando Whitfield, who here paints a portrait of the shifting ways in which art heists have been perpetrated – and perceived.

In many ways, a contemporary art gallery has a lot in common with a courtroom. Both are places of high spectacle, of lofty judgement, enforced decorum and politesse. People dress up to attend both and often leave owing vast sums of money (possibly overcast with fear or shame). It has always seemed odd to me, therefore, that when art dealers end up on trial, they do such a good job of looking out of place, of seeming shocked to be there. A good blue suit, it seems, will only get you so far.

Art dealers are synonymous in the public imagination with big money and dastardly behaviour. (I once briefly dated a woman whose family beseeched her to break up with me solely because I owned an art gallery.) And so, when considering how to pull off a fine-art swindle, it can be a little difficult to choose from the bright and varied palette of available criminality. Cicero wrote, “To be ignorant of what came before you is to remain forever a child.” Fortunately, the history of art-market criminality provides us with plenty of lessons in deception and scurrility.

When I tell people that I’ve recently published a book about fraud in the art market, their questions tend to go straight to art forgery. They picture a little old man in a remote Tuscan village, painstakingly putting the finishing touches on an as yet “undiscovered” Leonardo. This new-old painting then makes its way to market via a network of beret-wearing scallywags, all of whom smoke ominously and from the sides of their mouths, despite the conflagratory risk to their precious cargo.

This image comes, of course, from Patricia Highsmith novels and Hollywood movies starring hirsute billionaires, but it does have roots. One such forger (Dutch rather than Italian) was Han van Meegeren, the most prolific and successful forger of Vermeer paintings. Van Meegeren was canny in his choice: not only were Vermeer paintings incredibly valuable and sought-after but there were also very few of them (there are probably only 35 in existence). The discovery of “new” works by the Dutch master was welcome news to gullible buyers. Working from the basement of his house on the French Riviera, Van Meegeren used Bakelite to form an authentic-looking craquelure on his paintings.

Van Meegeren is remembered in the Netherlands as something of a national hero. During the Second World War, Hermann Göring traded 137 looted Dutch paintings for just one of Van Meegeren’s fake Vermeers. Van Meegeren thereby helped to safeguard precious national heritage – and got one over on the Nazis. After making and selling more than a dozen fakes (and becoming hugely wealthy in the process), Van Meegeren was caught and put on trial. He died in 1947, months into his prison sentence, at the age of 58.

What Van Meegeren did right was to select an artist to forge whose work was scarce. Half a century later, however, Iranian-American Ely Sakhai pulled off a fraud scheme with a brazenness that employed the opposite approach. Sakhai, who speaks fluent Japanese, knew that what most concerned new collectors in Japan was authenticity. So he trawled the auction houses of Europe and America, exclusively buying minor works by major impressionist artists, from Monet to Renoir, that came with certificates of authenticity. He would then have the painting expertly copied and sell the facsimile, along with its original’s certificate, to a Japanese collector. This went on until one of the buyers decided to sell, and a sharp-eyed auction-house employee in New York spotted what appeared to be the same Gauguin painting for sale in two different auctions, continents apart.

What elevated Sakhai’s scheme above that of a forger such as Van Meegeren was that it exploited a weakness in the art market of its day. Collectors, especially new ones, knew next to nothing, and with no internet databases available, they were flying blind, forced to trust their dealers. These days, with the price of practically every artwork that sells at auction available online, you must become ever more creative if you’re going to pull off something lucrative.

Perhaps part of the reason why forgery is the art crime that first comes to people’s minds is that it at least involves some artistry. But contemporary art, which is where the money is, is too tricky to fake; for one thing, the artists are often still alive. Nowadays, art crime has gone the way of the market, and it is increasingly financialised. As Damien Hirst once said, “Art’s about life; the art world’s about money.” Today art is all about the money.

All this is to say that art fraud today is, by necessity, a far trickier beast; one that is more contractual sleight of hand than imitated brushstroke. Take my former friend and business partner Inigo Philbrick. His fraud scheme, which clocked in at more than €79m, is thought to be the largest in US history. The swindle was wildly complex – like a Hollywood bank heist but carried out over emails and Whatsapp. The simplified version is that he would sell the same painting, or shares in that painting, to multiple people. In one instance, Philbrick sold 220 per cent of one multimillion-dollar painting – obviously 120 per cent more painting than exists.

There are several things to analyse here. Since art has become an asset class of its own, dealers and collectors have begun to buy works that they have no intention of hanging in their galleries or penthouses. Instead, the artworks languish in tax-haven warehouses until they have increased sufficiently in value. These kinds of buyers also often buy percentages in paintings to mitigate risk. Philbrick kept physical control of these paintings, ostensibly so that he would be able to arrange a client viewing at the drop of a (top) hat, but in reality so that he could sell the same work over and over. And what happened when two buyers both wanted control of a painting they owned (or thought they owned)? Philbrick simply sent them a blank canvas in a crate to their Swiss warehouse, where it remained unopened.

There are many different ways in which you can pull a fast one in the art market, though as with many get-rich-quick schemes, you’re more likely to end up counting the bars on your prison-cell door than your fortune. We’re fascinated by hucksters and villains but to me this seems a great sadness when it comes to the art world. When we obsess over fraudsters and their grimy actions, we forget ourselves. But perhaps our preoccupation with art crime also tells us how important art really is, how it can enrich us far more than mere lucre. We would do well to remember that.

About the writer

Whitfield is a writer and author of All that Glitters: A Story of Friendship, Fraud and Fine Art, which was published in 2024 by Profile.

publishing

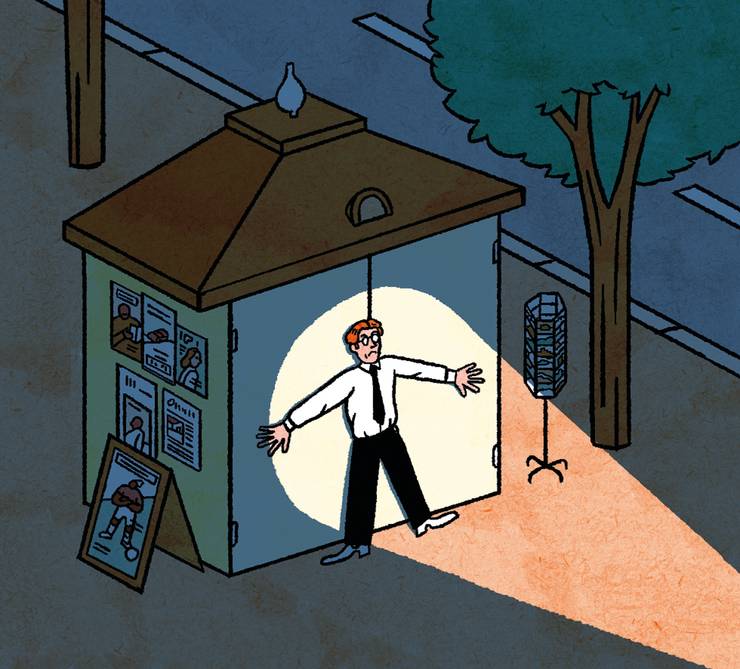

Keeping press freedom alive in Hungary

Zoltan Varga

It’s not easy running a media company in Viktor Orbán’s Hungary. Zoltan Varga, the Central European country’s last independent media mogul, tells us about spyware and smear campaigns, expanding further into the region and why his job is equal parts business investment and equal parts mission.

We are currently celebrating the 10th anniversary of our purchase of Sanoma Media Budapest, which we renamed Central Media, one of the leading magazine and online publishers in Hungary. In 2014, I was a private equity investor and I was motivated by the fact that it seemed like a good deal. Initially we wanted to sell on the assets at a nice price but we understood that if we wanted to keep independent, free media alive on a large scale in Hungary, we had to protect it. So we decided against selling to the government, aware of the effect that it might have on the country’s media landscape.

We realised that, if we were going to survive, we also had to grow beyond Hungary. So that’s why we invested in Slovakia, Czechia and, last year, Poland. In the last of those three countries we became a shareholder in Gremi Media, which is the publisher of the daily Rzeczpospolita, the oldest and most respected newspaper in Poland. Slovakia is interesting for us too, because free speech is also under threat there. It’s a buying opportunity, given that we have spent the past decade learning how to fight against oppression.

It is challenging at times. We have been attacked by investigations and spyware, and also faced character- assassination attempts. On the other hand, it has been good training for my mission to advocate democratic values and freedom of speech throughout the region. We gained ample experience in Hungary through being the underdog yet building a thriving independent media portfolio that informs and helps people to read news and analysis that they would not get elsewhere. We have found a way forward to counter propaganda in countries run by populists and make a free media business flourish.

We have more than 50 titles in Hungary. Our bestseller is Nok Lapja, which is the oldest women’s newspaper in the country. It shifts more than 140,000 copies a week. It’s all about families and family values, and is completely free of politics. But that hasn’t stopped politicians approaching us and hoping to be covered in it. We’ve said no every time.

We get absolutely no revenue from the state, which is a big deal given that the government is the biggest advertising spender. And yet we still survive. We are a profitable company because we have fantastic titles and good colleagues. And we were somehow able to adapt to the circumstances, which makes me think that we can do the same in Slovakia despite the new situation we are facing there under the current government [of populist prime minister Robert Fico].

For me this is not only a business but also a mission. Press freedom, factual news coverage and commentary based on critical thinking ensure that people make informed decisions about their lives and their broader community. We have a duty to inform citizens and give them the right to have the proper information. Simply put, a nation can’t evolve without these principles.

About the writer

Varga is the ceo and chairman of Hungarian media group Central Media. You can hear an interview with him on episode 633 of Monocle Radio’s The Stack. As told to Fernando Pacheco.

dining

Why Vienna’s restaurants are an education

Josh Fehnert

A few days in a new city are enough to see what your hometown gets right and wrong in the restaurant stakes. Our editor offers some lessons from a tasty escape to Vienna.

Peruse the hospitality headlines or cringeworthy year-end restaurant round-up lists and you’d be forgiven for thinking all the openings worth booking materialised in the past month or two. Not so. Of course, novelty nourishes the food industry but remember that only a fraction of these flash-in-the-pan openings may still be trading in a few short years. It’s an understatement to call hospitality a demanding industry and fortunes – like a sloppy soufflé – can fall as quickly as they rise (in both cases due to imperfect concentrations of hot air).

What’s more, it may take some places time to tinker with service, perfect the patter to be worth visiting at all: truly great restaurants can sometimes be measured in generations rather than seasons or by a single decent service when the reviewer rolled around. If there’s one city that mingles the hard-won, time-tested lessons with a little ingenuity, it’s the Austrian capital. Here’s what I learned on a recent Viennese whirl.

How to perfect a polite goodbye

Dinner at the recently redecked Reznicek in the 9th district is a pleasure. Simon Schubert and Julian Lechner have done a peerless job with the careful wooden fitout and seasonal menu, and they deploy a pleasing sleight of hand when it comes to politely telling guests to kindly bugger off. When it came time to turn our table (those people sipping Sekt at the bar were indeed waiting for us to leave), our hosts wheeled out a wooden trolley groaning with Viennese wafers, sweets and brownies in cut-glass cases and bowls, and a wooden box of cigarettes. “Sorry you won’t have time for dessert today,” was the practiced, friendly refrain. “But please help yourself to anything from the takeaway treats wagon.” It turns out that there is an elegant way to turf out the foot-draggers. London restaurants take note

That not all seats are equal

If you haven’t booked, then expect a queue for a weekend table under the red awnings of the peerless 400-year-old Zum Schwarzen Kameel restaurant in the city’s Gold Quarter. But Vienna is also a city of manners and means. Dropping an academic title on a booking here might secure you a better table (doing so in London or New York may only raise a giggle). We queued outside ahead of a posse of impatient twenty-somethings in designer threads who were tutting and huffing a cigar in mock disbelief at the impertinence of the short delay. They weren’t our crowd, so one of our party acted decisively. A quick smile, some beginner’s German and a natter to the front of house (we didn’t mention monocle, but we did enquire about some space with the grown-ups inside). We were whisked to a wood-panelled booth in moments. As our drinks arrived, and the drizzle began beyond the window, our restless acquaintances were being chivvied to a rowdier section outside and seemed rather happy with their lot. Everything was in its right place – a great front-of-house sees such things as this done effortlessly. A great restaurant makes space for many tribes too.

How family are the brand guardians

Generations-old businesses seem to be everywhere in Austria, and at its best having a surname above the door can indicate a proprietor who keeps things, well, personal. That’s the policy of Peter Friese, who has run Zum Schwarzen Kameel since 1977, and who personally oversaw the busy service, clipping across the cobblestones and then the baize carpets, past the ornate bars and sandwich counter, all while directing his fleet of white-jacketed waiters towards empty glasses and rumbling tums. You won’t see that in a venture-capital-backed “concept”, or if successful restaurants suddenly open 10 offshoots. Perhaps it’s one reason why the dark-furred dromedary has survived across the centuries.

Why cities should be themselves

Vienna has Catholic taste in several senses: there’s much to recommend it, something for every taste and an almost sacral regard for closing the shops on Sundays. I needed to fight my knee-jerk instinct for suggesting that Austria should reform restrictive trading hours for the convenience of visitors. But keeping them also has a pleasing flipside for residents. Perhaps the Austrian capital just doesn’t want (or need) to be too like Tokyo or New York? Perhaps people want a rest instead? While it’s an inconvenience for tourists who have forgotten a toothbrush and need a replacement, not many locals seemed to be grousing about it on their serene Sunday strolls around the Stadtpark.

That not all change is good…

One discovery was made on my pilgrimage to coffee and confectionery shop Julius Meinl. You may know its famous logo, of a boy in profile wearing a fez, apparently evoking the trade routes that brought coffee to Vienna. The marque – already a classic – was refined to a monochromatic silhouette in 2004 by Matteo Thun. Today it’s suddenly absented from the shop’s gourmet food packaging and the sign above the flagship on Graben in the 1st district. I would’ve gone into the shop and asked: why ditch a beloved logo for what I imagine are reactionary tastes that will likely change again tomorrow? But no one was around to comment and the shop was shut: it was Sunday, after all.

…and how ageing gracefully is underrated

If you only go to one café, swerve the tourist traps and try Die Cafetière: a recent tip-off on Wipplingerstrasse. Owner Peggy Strobel took over the former Naber Kaffee shop and roastery in 2023 – the space is replete with cream tiling, dark wood and a perfectly politically-incorrect mosaic of a turban-wearing coffee-drinker in front of a minaret outside. While common wisdom might have told her to gut the place and build something that could be turned into a chain or flipped, Strobel kept the original curving 1960s bar with its brass detailing and brolly stand. There’s a ceiling fresco and tiled walls, to which she has added a fetching Thonet showroom at the rear with additional seating in a wonderfully mid-century-feeling space. That’s before I riff on the homemade pastries and the just-so house-roasted beans in the Grosser Brauner. This may not be the way to get rich but it is the way to run a super little café that can teach us all a thing or two. In hospitality it can pay to rebuff the trends, endless refits and the restaurant round-up lists. A recipe for success can take time to perfect.

About the writer

Fehnert is monocle’s editor. His appetite for a food-related scoop and a comfy bed means that he commissions our restaurant and travel pages.

defence

Why Germany must rearm

Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann

A strong, armed Germany could lead the way in Europe and show aggressors that it’s ready to act to maintain the rules-based global order. One German MEP makes the case for Germany arming itself.

Germany needs to rearm – but it’s easy to understand our aversion to the idea. We have to explain to people that if they want to live in a free and peaceful Europe, we need a strong military so that nobody thinks about attacking us.

Germany’s current aversion to defence comes from our history. During the 20th century our country was responsible for two huge global conflicts. It has been vital for us as a society to reckon with the past. That was the reason why the Allies dissolved the Wehrmacht, and everything military-related, in Germany after the Second World War ended. But our current predicament is dictated by more recent history. Germany rearmed by the 1950s as the Cold War intensified. In 1955 the Bundeswehr (Armed Forces) was founded and what was then West Germany became a member of Nato. After the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, the Bundeswehr grew. Germany already had conscription in place and by the end of the 1960s there were about half a million soldiers under arms. In 1964, Germany spent nearly five per cent of its gdp on protecting itself. At the end of the 1980s, the German defence budget was nearly €60bn.

So what happened? The wall came down and, with it, the main threat disappeared overnight. Since the 1990s the number of soldiers under arms has dropped. Today our active-duty army stands at about 180,000 soldiers; we paused conscription in 2011. Germany militarised with the construction of the Berlin Wall and de-militarised when it came down. Now that paradigm needs to be rethought.

Germany, like other European countries, has been lulled into a false sense of security. This was true in the Germany I remember when I was growing up. Many thought that the Cold War was over and the paradise we had been longing for had arrived. There was no place in our collective imagination for the idea that the situation could change and war could return to our continent.

Even if the majority of the Germans alive today weren’t even born at the time, our commitment to peace remains our collective responsibility. An anti-military sentiment has been passed down through generations. Our history means that the military isn’t a popular topic. Whenever previous governments since 1990 needed money, they looked to take it out of the defence budget – and many people didn’t care.

That’s why our Armed Forces are run down today. In 2022, an investigation revealed that Germany only had ammunition to last a few days at war; defence minister Boris Pistorius said that there wasn’t enough money put into the military in the draft 2025 budget. The legacy of the Second World War, the fear that one day Germany might be responsible for another war, has left many people paralysed, afraid to make important defence-related decisions.

The very countries we attacked 80 years ago don’t suffer from the same issues. The best example is Poland. Many friends there now say that they are more afraid of Germany being too weak than too strong. Instead, they’re waiting for Germany to lead Europe’s military recuperation and counter Russia’s aggression. As Europe’s largest economy, it makes sense that Germany should play this role. We have rebuilt trust since the end of the Second World War. But it is also a strange position to be in. Everyone around us seems to believe in us but we still don’t trust ourselves.

So when Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula in 2014 and launched a full-scale invasion in 2022, it took Germany time to wake up. But full-blown conflict did prove enough to stir us from our slumber. If you compare the state of our army currently to how it was just a few years ago, we have achieved a lot. A key moment was chancellor Olaf Scholz’s “Zeitenwende” speech on 27 February 2022, three days after Russia invaded Ukraine. He promised a historic turning point in Germany’s defence policy. A €100bn fund was created by finance minister Christian Lindner to increase military spending and we began to send weapons to Ukraine. But, despite this, the situation is incomparable to our army’s strength before the 1990s.

When I started studying political science at university, I had a conversation with a professor. We were focusing on Japan and its territorial dispute with Russia over the Kuril Islands, just above Hokkaido, that have been occupied by Russian troops since 1945. It had been framed as a frozen conflict and we were questioning whether it really is possible to “freeze” a dispute. At the time we were all in disagreement. But I know that if I was having the same conversation now, my answer would be a definitive “no.” It might be the best way to handle a problem for politicians in the moment – pressing pause on an issue and seeing what happens next. But when I was in Japan in March 2023, I met the defence minister and encountered the same questions that I had discussed nearly 45 years earlier as a student. It’s no use freezing a problem and handing it down from one generation to the next. We must solve issues here and now.

Germany’s most recognisable recent leader, Angela Merkel, became infamous for freezing conflicts. When Russia grabbed Ukrainian territory in 2014, instead of leading other European countries in a strong response, Merkel dithered and hid behind the excuse that other European countries had to be consulted. But the hypocrisy couldn’t be more obvious; when it came to taking decisions such as striking a deal with Vladimir Putin over cheap Russian gas through Nord Stream 2, Merkel acted alone and against the interest of our European partners. In the end, the 2014 Minsk agreements suspended Russia’s attack on Ukraine for a little while – and we all know how that turned out. Merkel’s foreign policy was a total failure. She never explained that military problems could arise for Germany as a result of Russia’s actions. Instead, she promised something ambitious yet vague. In fact, her re-election slogan was, “Für ein Deutschland, in dem wir gut und gerne leben.” (For a Germany in which we can live well and like to live.)

Today’s politicians need to be clear with the German public: the situation has changed since the 1990s and will do so again. It’s natural that citizens are more preoccupied with everyday economic issues and their children’s prospects than defence spending. But a government’s job is to explain the risks and demonstrate how they are managing them. With its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has shaken the rules-based international order, which is the foundation of all international relations. That Russia would actually send troops into Ukraine was inconceivable for many before it happened. If Ukraine loses this war, there isn’t only the danger of Putin showing up on our borders next. There’s also the danger of a copycat effect. China might decide to force Taiwan under its control; Iran has already attacked Israel; Serbia might decide that Kosovo has been independent long enough. If the rules-based international order collapses, peace and freedom are at risk. The mere idea of the EU as a civil power would become obsolete.

There is no doubt that we have the chance to live in a positive future. But for that to happen, Germany has to get rid of the fear rooted in our history and show real leadership. Putin knows that most Germans will want to block out terrible stories of war and focus on improving their own lives (“living well”, as Merkel called it). Let’s not forget that Putin lived in Germany, speaks our language and understands our mentality well. But voters here have a choice.

About the writer

Strack-Zimmermann is a German mep and a member of the German fdp and Renew group in the European parliament. She is the chair of the security and defence committee, and previously a member of the Bundestag. As told to Julia Lasica.

intelligence

How female spies remain invisible

Ava Glass

The world of spying is full of drama, glamour and sex, or so it would appear if you read the classic novels. Our author, who worked with spies, tells us how women in espionage are almost entirely absent from these stories and, when they do show up, are nothing like the real thing – which can serve as a pretty decent smokescreen.

The first spy I ever met fooled me completely. In the early 2000s, after a career as a journalist and editor, I had been offered a job working for the British government as a counter-terrorism communications consultant. It was, in some ways, the traditional tap on the shoulder – an old colleague approached me directly, asking if I would be interested in the work. I found the offer too intriguing to turn down. My job was to explain to people what intelligence agencies were doing and how they worked; to get past the Hollywood myths and make spies real.

Before I could start, I had to get security clearance. This was a mysterious process in which I answered about a dozen questions and then everything went quiet for weeks until my government pass arrived. I was in – or so I thought. But once I was through the secure glass doors of the Westminster office, I had very little to do. Nobody said anything but I got the impression that they were waiting for something.

It was then that I was befriended by a young woman. She was about 28 years old, with wide blue eyes. She said that she had just started working in the legal department. We had a brief conversation while making tea one afternoon. I didn’t think about her again until a few days later, when I ran into her on my bus after work. We sat together during the journey and decided to go for a coffee the next day.

Over the next few weeks, we often had lunch together. She asked about my family and background. I’m a sharer and I chatted away happily, right up until the moment she disappeared. And I mean she really disappeared: her phone number, her email address... everything was gone. When I asked around the office, nobody could remember her. It was as though I had met a ghost.

Almost immediately though, things changed for me. I was invited to meetings that had been closed to me before. My work began in earnest. And gradually I realised that the friendly blue-eyed office worker had been a spy. She was the last step in my background check. Of course, I’d known from the start that I would be working with spies – that was the point – but I had never suspected that she might be one. This was because fiction had never shown me a spy like her.

What little we know about spies we learn from books and films. In fact, most of what we believe comes from just two writers: Ian Fleming, who created the Bond fantasy of the dashing, charming, Etonian spy; and John le Carré, who brought us the realpolitik of bitter, jaded men in rumpled suits and unheated offices, undermining each other while duelling with Soviet agents.

There have been other successful spy novelists, of course, but our collective vision of spies still largely comes from the work of those two British men and, to a lesser extent, the books of Len Deighton and Graham Greene. Their novels form the accepted canon of the genre against which all modern spy novels are still judged. And yet all those authors failed to write believable women characters.

Fleming’s women were blow-up sex dolls with ludicrous names such as Pussy Galore and Holly Goodhead. The women in Le Carré novels were absurd in a different way, presented as either the “mothers” – his word for secretaries in mi6 offices – or Connie Sachs, an ageing, sex-mad alcoholic. Aside from an occasional minor character or traitorous wife, we don’t see other women in the books lauded as the greatest spy novels. They simply aren’t there.

I believe this is why I am constantly asked whether there really are female spies like the ones I write into my novels – normal women doing extraordinary jobs. Over and over again, I tell people they exist. I explain that the actual Q (the technical genius in the Bond novels whose job exists in real life) is a woman. And that three of the four current division heads at mi6 are female. I can’t blame them for being surprised. After all, I was surprised to meet so many women spies.

Naturally, mi6 is aware of this. Recently, it has been recruiting more women, and one of the biggest blocks it finds is that women don’t realise they could be good at spying or that they would be welcome in intelligence. One advertisement that the service ran a few years ago showed a mother with a small child and the words, “Secretly, we’re just like you.” And they are. The women I met during those years were of all backgrounds and classes. Some were approachable and open, others incredibly intimidating and formidable. I met a lot of male spies too, of course, but the scariest spy I ever met was a woman.

She had a freezing stare that seemed to stab into the most shallow and insignificant parts of my soul. I was certain she could see all my faults through my skin. She was in her sixties, weathered and disdainful. I might never have met her, but she was invited to a meeting about a major forthcoming event. Everyone else in the room – all male intelligence officers – deferred to her. She was, I suspect, the most senior person I met in intelligence during my career, although her rank was never revealed to me. All I knew for certain was that she had no time for someone like me telling her that spies should talk publicly about their work. I’m not easily intimidated but in that meeting I found myself fumbling my words and saying inane things. I couldn’t wait to get out of the room.

She was entirely different from the first female spy I encountered. In that case, it was her sheer ordinariness that made me never question her. She was so normal in her brown skirt and slightly scuffed boots, with her hair pulled back. She had a vicious sense of humour and was so convincing that I believed everything she told me. And yet every word she said was a lie. I’ve wondered for years how she could have been so smoothly deceptive at such a young age.

If I had known my history then I wouldn’t have been surprised. Female spies, especially young women, have been critical to intelligence for decades. Consider Nancy Wake, nicknamed “White Mouse” by the Germans during the Second World War. Wake was a British spy who joined the French Resistance aged 29. Working first as a courier and then as a member of the Escape Network, she helped numerous Allied airmen slip out of occupied France to safety in Spain. After fleeing France in 1943, she later parachuted back in to help British intelligence organise French guerilla groups. She was never captured and died in 2011 at the ripe old age of 98.

Then there was Virginia Hall, an American socialite who lost a leg in a hunting accident before the Second World War but still travelled to France to offer her services to the Resistance. Fiercely intelligent and utterly without fear, she eluded the Nazis throughout the war, carrying critical messages for British intelligence and uniting rebel groups, running operations that changed history. The Germans knew her only as die hinkende Frau (“the limping woman”). She became their most wanted Allied spy but was never caught.

Authors Ian Fleming and Graham Greene both served in intelligence alongside Virginia Hall during the war. They would have known about her and Nancy Wake, and the other female spies who risked – and often lost – their lives. Even though he came into the firm later, a scholar such as Le Carré would certainly have heard of them.

They knew about these female spies. Some even met them. And then they wrote those women out of their books. It was so consistent across all the male espionage writers that it couldn’t be an accident. But why would men who knew about these fascinating women choose not to represent them in novels about spies? Of course, we will never know the full truth, but I believe it was fear.

Consider that Graham Greene was born in 1904; Ian Fleming in 1908; Len Deighton in 1929; John le Carré in 1931. They lived at a time when women were in no way equal, for most of their lives unable to buy a home without a man’s permission and unable to have a bank account of their own. Often they were fired as soon as they were married. Then the war came along and everything changed.

Everyone was needed and it turned out that, among many other things, women were very good at spying. How intimidating that must have been for someone like Fleming, a writer with minimal ambition who got a job in intelligence thanks to his mother’s connections. Imagine him in a room with Virginia Hall. She must have had an icy stare like that older female spy I once met. Ruthless, brilliant, unforgiving.

When Fleming and his generation penned their novels years later, the women they wrote weren’t brave or intelligent. They were sex toys or traitors. Because these writers had worked in intelligence, people assumed they wrote what they knew. But they didn’t; they wrote what they wanted us to believe. But there’s an oddly positive twist. By ensuring nobody knew that female spies existed, those authors unintentionally made life considerably easier for the women who really hold those jobs. Yes, it’s galling to be written out of fiction but if people don’t know you exist, they never see you coming. You can slip in and out of their lives unnoticed. Like a ghost. And that’s the best gift you could give a spy.

About the writer

Glass is the cwa Dagger-shortlisted author of spy novels The Chase, The Traitor and The Trap. A former crime reporter and communications consultant, she worked closely with spies for five years and they inspire every book that she writes.

q&a: diplomacy

Mightier than the sword

Luxshi Vimalarajah talks to Ed Stocker

For every conflict that rages, there will be those behind the scenes striving to resolve it through diplomatic means. One such mediator, from Berlin’s Berghof Foundation, tells us the key steps to resolution.

Senior peace mediation adviser Luxshi Vimalarajah, who has spent years as a practitioner worldwide, from Myanmar to the Basque Country, here sheds light on the minuscule details that need to be taken into consideration when bringing opposing sides to the table.

Many people dream of being astronauts or musicians. How did you get into mediation?

It has a lot to do with my childhood. I grew up partly in Sri Lanka when the civil war between the state and Liberation Tigers of Tamil was in full force. Thousands were displaced and fled the country during that time. Negotiations took place periodically but they were seen as a war by other means: it was all about defeating the other side at the table or a tactical move to gain more time. I grew up watching these negotiations, which were a failure. Both sides were insisting on these maximalist goals and were unwilling to negotiate in good faith. There was also deep mistrust and huge asymmetry between the parties. The Sri Lankan state had access to the international community, to resources and to power. The other side didn’t. How can you resolve a deep-rooted conflict like that? How can you help the parties to make the shift from violent politics to non-violent? So those two questions were key for me and led me to study political science and then specialise in peace mediation. The Sri Lanka conflict helped me to understand the tool of mediation and what assets a third party brings, as a go-between and an honest broker. The third party helps to level the playing field and find common ground.

It must be so hard remaining impartial or neutral given that it is part of human nature to form opinions. How do you do it and foster that skill?

As a mediator, you are expected to be impartial: free from bias and treating all conflicting parties in an even-handed and fair manner. You are equidistant between the parties. You don’t have any stakes in the outcome of the agreement or the negotiations, and you try to provide the space for both parties to negotiate an amicable outcome. Nowadays we insist that we are not neutral third parties; we also bring our ethics, our values and how we see the world into a process. And so it’s not whatever the parties want; there are clear limitations. Some parties enter a mediation process thinking that they can negotiate blanket amnesties for the crimes committed during the war. They sometimes even make it a precondition. However, we are bound by international humanitarian law and UN mediation guidelines that prohibit amnesties for gross human rights violations and crimes against humanity. We try to be as impartial as possible but it’s not always easy. There are moments when it might be better to step out of the process and bring another third party in.

What makes a good mediator?

Sometimes parties want to have a more authoritative mediator who tells them how to manage a conflict. But in other cases, parties just want to have a space where they can explore options and be provided with ideas. For instance, [Finland’s former president] Martti Ahtisaari in the Aceh process [in Indonesia] was seen as a very authoritative figure. He structured the process and provided the space but he also made it clear from the outset that a separate state for the gam militants was off the table. You might have question marks about such an approach but sometimes parties do prefer to have that.

Are there golden rules?

Never seek to embarrass your adversary. You have to create a situation where none of the parties really lose face, particularly in an Asian or African context. It is so important that you set a framework that allows parties to retain their dignity. The golden rule in our field, just like in others, is to treat others as you would like to be treated yourself. So this obviously encompasses respect, fairness and engaging in negotiations in good faith. These are the golden rules that I always apply in mediation processes. Elsewhere, an approach that really helps parties to see how they can make this shift is called the Harvard Principled Negotiation. These are all about moving from positions to interests. It’s not about what you want. Usually parties are stuck with: I want independence; I want a unitary state; I want this and that. But these principles dig a bit deeper and ask the questions of why they need it. This shift from what to why is quite important. Interests lie below positions and that’s a way in which you can accompany the parties to see not just their own interests but also the ones on the other side.

This could lead to agreement through compromise?

Compromise is not a term I use. We tend to think that if parties are in conflict, they have to find a compromise. Both sides will probably not be satisfied but they have to somehow meet in the middle, right? But this isn’t something that I propagate, because neither side gets what it wants. It is a lose-lose situation. There are many ways to deal with conflict and the more prominent one is one side gets what it wants and the other doesn’t – a win-lose paradigm. But what we try to do is to find a way in which both sides may get what they want.

It is hard and it also takes a lot of time to understand how we can find a mutually agreeable solution based on these underlying interests. Do you know the story about a fight over an orange between siblings at home? There’s just one orange left and both children want it. What would a mother normally do? Cut the orange in half and give each child an equal share. That feels fair as it’s half and half. So that’s the classic compromise situation. But both children end up unhappy. And they begrudgingly accept the solution. But what could have made the situation better, do you think?

Tough one. What about giving one child an orange today and the other child another tomorrow?

It’s actually very simple. The mother should have asked why they wanted the orange. We usually assume that both want to eat the orange and so we cut the orange in half. But if she had asked the children, she could have made a better decision. Because it turned out that one wanted the orange to make juice and the other one needed the zest to bake a cake. And both would have got what they really wanted if the mother had asked the right question.

You must have to be fastidiously aware of every tiny detail when bringing opposing sides together.

Tiny details matter a lot. When you come into a process and the parties have not met you but might have heard a lot, the perceived weaker side always assumes that you will most probably privilege the stronger party, which is usually the state. Without even knowing how you conduct the process, they always assume that you are biased towards the state. And so these assumptions drive the way they behave at the table. The first two or three rounds are always a testing phase. Who does she shake hands with first? Is it the state or us? How does she sit? Does she frown when we speak or just when the other side speaks? Why is she shaking her head? Every minor, non-verbal expression from your side is observed. My formal sessions always start with an informal moment, checking all these details, from seating plans to how I’m going to address them. Do they have a preference to speak first, or can we let the other side speak? So it’s a major drama. One process I was involved with almost broke down because we hadn’t checked all these details. It’s exhausting but I always say that preparation is everything. My rule of thumb is: if you have a two-day session, you need to take four days to prepare for that.

I see you are currently involved in ‘discreet’ mediation in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. Can you shed more light on these processes?

I mean, they’re discreet, so I can’t say anything! Perhaps the most successful mediation processes are those we don’t get to really hear about, because they happen long before any conflict breaks out. We know mediation as a tool to resolve conflict but we hardly pay any attention to its preventive function. It’s not widely covered but it is powerful to really prevent the outbreak of conflict and violence in the first place. A lot of mediation happens behind the scenes and when parties are ready to explore other options, because they know that if they don’t, they’ll end up in a violent conflict.

Do you have a most memorable moment from your time in the field?

One was in 2008 when members of the Basque movement approached the Berghof Foundation and asked whether we could assist eta [an armed separatist group] and the wider Basque movement to transition away from violent politics. eta was banned in those days as a proscribed terrorist organisation, yet it was willing to consider laying down arms – but only in a dignified way. It wanted to have a negotiation process and a plan for demobilisation. The Spanish state insisted that if eta wanted to demobilise, it should lay down arms, and it resisted negotiating with eta. For us, it was a very unusual process accompanying an armed movement but it was an important one, because we were fearing what would happen to the weapons, to the people in exile and on the run, to the active militants and the wider Basque community. How could we encourage more inclusive processes so that the Basque community itself was involved in such a transition and not simply a bystander? How could we prevent further radicalisation and polarisation in a situation where there was no negotiation process with the Spanish state? Over two years, I was engaged in a quiet process with several sections of the Basque movement, facilitating their internal strategy-building process. I brought them together with movements that have undergone a transition process successfully – such as Sinn Féin and South Africa’s African National Congress – to learn from them. We gave negotiation training to the Basque political arm known as Abertzale Left, and helped to provide options for the inclusion of civil society in the peace process. We were involved behind the scenes throughout the whole process, from the initial cessation of hostilities to eta’s eventual demobilisation.

How do you convince two people who don’t want to be in a room together to actually sit down in a room together?

I’m always asked this question these days in relation to Ukraine and Russia. I always say that mediation is a voluntary process. It’s also not a silver bullet. We have to have certain conditions in place for it to work. One of those is a willingness from both sides to settle the conflict and the realisation that continuing the struggle will be more costly than ending the conflict. There often needs to be what we call the mutually hurting stalemate: a situation where neither side can really win the conflict, leading to a situation of lose-lose. Only when parties see that – and want to have a different way of engaging with each other – is the time right for mediation.

Your orange story earlier makes me think about mediation in a domestic setting. What are the lessons that we can apply to avoid arguing with our partners or children this Christmas?

Mediation is all about communication. It’s important to ask the right questions and not jump to assumptions. Avoid “yes” or “no” questions and leading ones such as: “Do you think he was right when he said X or Y?” That puts people off. Instead, be curious and try to understand the other person. So, “Can you tell me more about what triggered this reaction of yours?” Dig deeper, put yourself in the shoes of the other person and try to understand what makes them uncomfortable. My second point is the need to listen actively. We don’t listen and instead are constantly thinking about what we are going to say next while our counterpart is talking. This means we don’t pay attention to what he or she says and that can be detrimental. You have to seek understanding before being understood. So listen attentively and actively to the other side before you start to talk yourself.

Do you find yourself using professional mediation skills that you’ve acquired during your career with your own family? Or do you sometimes throw that orange against the wall?

I recently had a conversation with a friend of mine. I was telling her that all my knowledge about mediation doesn’t work in this context. You also have limitations, particularly when you are a conflict party. You can end up resorting to the sorts of tactics that a conflict party uses in such a situation. So, it’s sometimes difficult to restrain. And then you have to reflect. It’s not easy but you can also learn that way. When I teach mediation to my diplomat students, I always tell them that they can go and practise in their personal life, because we’re constantly negotiating with our children, with ourselves, with our employers or employees. When we use mediation very consciously, it really helps to have a better relationship with the people around us.

About the interviewee

Vimalarajah has been at Berlin’s Berghof Foundation, where she is now senior peace mediation adviser, since 2003. She is involved in mediation processes in Europe and Asia, and helps to train diplomats from Switzerland, Germany and the EU.