Essays / Global

Looking forwards

Predicting the future is a notoriously tricky game, yet past experiences and current concerns can provide important clues – whether that is charting the success of bold urbanism, learning lessons from cultural controversies or simply imagining new histories.

1.

Ana Kinsella on ...

Why finding better ways for humans to live alongside each other should be at the heart of urbanism – even if, judging by some ideas that will be at play in 2023, we haven’t learnt from the past.

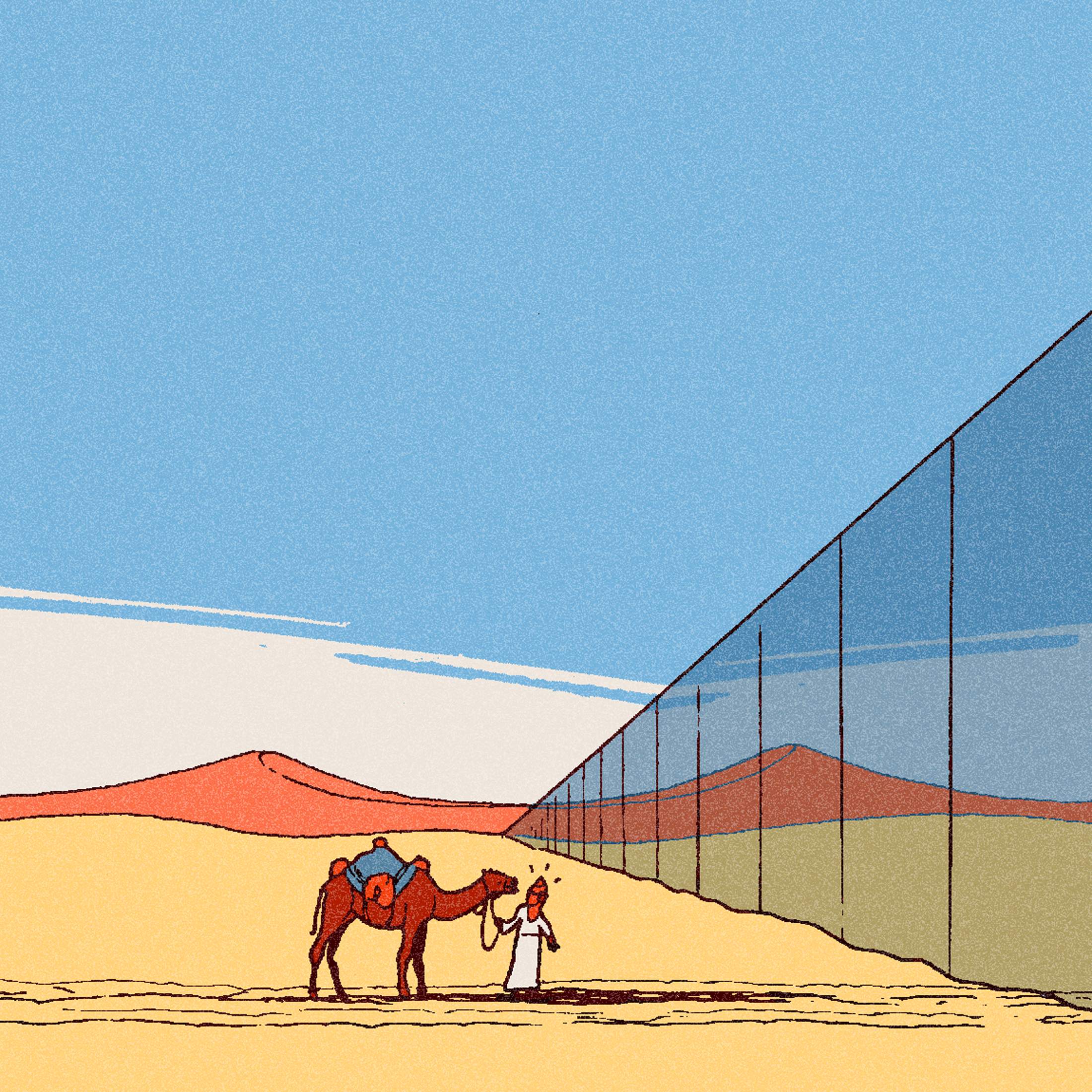

The Line, a planned megacity in the scorching Saudi Arabian desert, imagines a built-from-scratch place to live in a rather puzzling new format. It’s a linear city, for now unbuilt, which developers say will house nine million people in a mirrored space measuring 200 metres wide by 170km long. The costings and timings remain fuzzy.

As well as being an attempt by Saudi Arabia to woo foreign investors and score headlines in the architectural press, The Line promises residents everything they will need within a five-minute walk. The most unusual aspect of this take on the complete community? This walk never takes you along a street. The Line instead has a rather unromantically named “pedestrian layer” on which to move around and an ultra-high-speed train that runs from one end to the other in a mere 20 minutes. Handy? Perhaps. Exciting? Not so much.

There’s much to be said for the street as the connective fibre of a good, functional city. It is the way we access our homes, offices, work, coffee shops, theatres, parks, markets and all the timeless pleasures of urban life that have existed for millennia.

Streets are also democratic spaces that belong to the public. Money, class and status mean little to those sharing a pavement or waiting patiently to cross the road. They are places where we perform our shared citizenship, build social capital and feel like we are part of something bigger. It is harder to simulate this in an air-conditioned pod.

Another factor that makes streets special is that everyone has a right to be there. Only the very wealthiest can live in busy cities but totally bypass the street. And why would they want to? It is on the street that I am inspired, invigorated or simply reminded of why I chose to settle in London. It is also one reason that 80 per cent of the world’s population is expected to live in cities by 2050.

Whether you reside in Singapore, Sydney or San Francisco, walking the streets is surely what makes urban life enticing, serendipitous and strange. Proximity to the lives of other city dwellers is a feature of urban life to be enjoyed, not a bug to be ironed out. “Convenience” is the clarion call for The Line’s designers but that isn’t enough. In fact, some of the best cities in the world, from Venice to New York, are tricky places to navigate. Being able to get around easily and safely is a key part of a balanced city; ditto access to greenery, fresh air and space in which to amble or cycle. But so is space for collision, coincidence and chance encounters.

With luck (and a little common sense), cities like The Line won’t get much beyond the rendering stage. If you want to know what cities of the future should look like then planners should consider what tempted people to them in the first place.

About the writer: Kinsella is an Irish journalist based in London and author of Look Here: On the Pleasures of Observing the City, published by Daunt Books.

2.

Claudia Mader on ...

The issue of cultural appropriation surrounding wearers of leopard print and white people playing reggae music – and whether both claims are based on a reductionist image of human beings.

The issue of cultural appropriation surrounding wearers of leopard print and white people playing reggae music – and whether both claims are based on a reductionist image of human beings.

By now we all know a lot about cultural appropriation, right? You’d think so but we have neglected a key aspect. When it comes to appropriation, we have missed the most offensive thing of all.

When the weather is hot, you will often see shameless examples of offensive appropriation. It is there on bikinis, flip-flops, T-shirts and sunglasses: the leopard-skin pattern. This is what one British researcher recently called “the biggest case of cultural appropriation in existence”.

That research was backed up with numbers. In April 2019, the Shopstyle.com platform offered 19,049 leopard print products. At an average of $423 (€423) an item, the leopard-related turnover of this single shop came to an eye-wateringly large number. But do the leopards see any of that cash? They do not. Leopards give inspiration to countless humans; humans give nothing in return. This has got to change.

Therefore, the British research team came up with a proposal. Anyone using a leopard pattern should pay for it. The logic of a “leopard tax” would extend to events using the design in a trademark. (The Locarno Film Festival is one, if the Oxford researchers need any tips.) Details on how to levy the tax are still hazy but it is clear that the money could be used for animal welfare to benefit the leopards. Leopards are an endangered species and their numbers are dwindling but human beings just keep on using their pattern anyway.

In 2022, The New Yorker wrote about the leopard copyright project and it was picked up by the Swiss newspaper NZZ am Sonntag. When it was first reported, the leopard-print idea might have seemed just another oddball news story. But given how “appropriation” debates have continued to evolve, it is worth a closer look. We don’t normally think of animals in terms of “cultural appropriation”; we usually associate that concept with culture rather than nature. And there is genuine concern behind the idea when it is used in the context of endangered species. But the proposal to copyright leopard print also sheds light on the very idea of “appropriation”, a term currently making so many waves.

In mid-July, a concert in Bern was cancelled because a white band with dreadlocks had played reggae music, a form of “cultural appropriation” that some visitors found problematic. The pattern of animal fur is not the same as a musical style but the basic idea behind the claims is the same in both cases: there are groups of creatures that own certain things. This could be a distinctive combination of shapes and colours or a particular kind of song. People within a dominant capitalist culture find pleasure in these things, before taking them over and reshaping them to serve their own purposes: fashion designers put leopard print on clothing; singers make reggae records. What the two have in common is that they are producing a commodity to sell for a profit.

In both cases, the group of living beings that originally provided the inspiration has subsequently suffered profoundly as a result of the producers’ power, whether that is the destruction of animal habitats or racial discrimination against people from Caribbean islands. And neither group receives the profits associated with the “products” they inspired. Instead, the money flows into the pockets of the dominant few, ultimately propping up this system of oppression.

At its core, cultural appropriation is an economic issue, as theoretical treatments of the subject make clear. In 2021, for example, German social scientist Lars Distelhorst published a book demonstrating “how deeply cultural appropriation is inscribed within the capitalist logic of exploitation”. In fact, that economic element can be seen in the vocabulary. The term “appropriation” is closely linked to “property”; the language itself overlaps. “Appropriation” is taking someone else’s property – in other words, theft.

Many of our current discussions about appropriation are not about actual stolen objects. Looted colonial art, for example, is not the focus of these debates. Nor is the leopard’s actual physical fur: this isn’t about finite material things. Instead, the appropriation involves styles, forms and ideas. It is implicitly about the monetisation of these things. The logic of appropriation suggests that cultural practices, such as using a leopard pattern, can be seen as the copyrighted property of specific groups.

There are cases where strong market actors have unquestionably exploited the knowledge and traditions of less powerful groups. There are moral questions raised when large agricultural corporations make use of indigenous knowledge to produce new seed varieties without paying compensation. Likewise, when multimillion-dollar companies put out fashion collections that copy styles developed by African tribes, they are basically ripping off the work of people who lack the resources to promote their work globally – if, in fact, that is even something that those tribe members wanted to do.

That said, debates on cultural appropriation tend to avoid focusing on big international corporations. Instead, they centre on individuals accused of appropriating a culture that is not their own. Western yoga teachers have been condemned for commercialising teachings from India; American chefs are denounced for selling Mexican food; white painters are said to have used indigenous forms to achieve success on the art market; a Swedish designer stands accused of commodifying traditional Sami motifs. As a rule, these accusations are not about plagiarism – the copying of specific works – but rather the “exploitation” of general cultural content. Though it is rarely made explicit, a kind of economic logic underlies the entire debate. As Distelhorst puts it: “Most debates about cultural appropriation take place against a backdrop of the production and consumption of commodities.”

There is a lot to dislike about appropriation but the assumption of ubiquitous economic motivation is disturbing. It would be naïve to imagine culture without economics. But looking at everything through an economic lens distorts our view of human beings, as if our every move and action was driven solely by calculations of profit.

Human beings don’t need to think of each rhythm they hear as something to be exploited for money. The same goes for patterns of colour and types of physical training. Our species has a very special quality. We are able to take an interest in other living beings. We can actively engage with who they are and what they do. We are capable of feeling admiration for things that are present in the world around us.

If people open up to new phenomena, they should be able to integrate their discoveries into their own lives. The process could easily be described using words like “sympathy” or “appreciation”. But if everything is based on ideas of “appropriation” then appreciation is excluded. Rigid dualisms are introduced and everything becomes a question of ownership.

The existence of cultural “property” (that which is one’s own) implies the existence of its opposite: that which is foreign. Theories of appropriation cement this opposition, meaning that difference dominates everything. It could be said that our shared existence might bring about an exchange between living beings. But this isn’t possible in a theory claiming that groups should hoard their own cultural possessions.

Those who object to cultural appropriation and supposedly seek a world free from the logic of exploitation are typically on the left of the political spectrum. But thanks to ideas of appropriation, they are paradoxically encouraging the commodification of every aspect of life. By this logic, whenever an individual cooks, paints or knits anything, they are driven by commercial interest. In this world, all cultural forms and practices, everything from Rastafarian hairstyles to yoga positions, must be considered protected goods to be used or modified only by their “rightful” owners.

From this perspective, even animals become market participants, holders of their own copyright. Should endangered species be entitled to royalties? This logic implies that by devising clothes, jewellery and everyday objects, people have exploited nature’s forms and colours: stealing beauty which rightfully belongs to others.

If we are to have animal copyrights, we should probably start with the leopard, which promises to be the biggest revenue generator. Or, in the fluent business jargon of those British academics, the leopard has what it takes to be the “cash cow” of the jungle.

About the writer: Mader is a writer for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, where this article first appeared. It was translated for MONOCLE by Brían Hanrahan.

3.

Andrew Mueller on ...

The world in 2043, the story of the disintegration of empires and the continued rule of some familiar yet divisive faces, as imagined from the lofty vantage of 20 years in the future.

It’s 2043. If the past 20 years have taught us anything, it is that nothing lasts forever. Two decades ago, we lived in a tripolar world caught between three powerful entities: China, Russia and the US. Plus, bit parts for America’s allies in Europe and the South Pacific. Today, as I write this in 2043, none of those blocs still exist in the form that they once did. You shouldn’t be surprised: every empire that has ever declined and fallen believed that it would last for ever and so did most people protected or enriched – or indeed oppressed or exploited – by them.

Looking back, the disintegration of the US was, however, probably the most surprising development. At the second time of asking, the mightiest and wealthiest civilisation ever gathered beneath one flag was unravelled by the personality cult bafflingly consecrated to one of its least distinguished citizens. Donald Trump’s reelection to the country’s presidency in 2024 was, in retrospect, remarkable in a couple of key respects, neither entirely unprecedented.

Trump was not the first US president to have won a second non-consecutive term (That was Grover Cleveland in 1892). Nor was he the first person to have run for the US presidency from jail – or, if you will, for the White House from the big house. In 1920, Eugene Debs stood on the Socialist Party ticket from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary – and won almost one million votes nationwide.

Trump, as you’ll now know, did rather better than that. His conviction in 2023 on assorted charges of fraud relating to his years as a Manhattan real estate huckster ended up being an electoral boon, playing as it did into his narrative of persecution by the sinister deep state behind a vindictive federal government. His acceptance of the Republican nomination, delivered in the orange fatigues of New York’s Shawangunk Correctional Facility via telephone from behind a glass screen, had a predictably galvanising effect on his supporters.

Fears that Trump would sow chaos by contesting the election result proved unfounded, on the grounds that it wasn’t in his interests. A hefty plurality of American voters, presented with the choice between a seething felon and a calm, pleasant and efficient bureaucrat, awarded Trump a 296 to 242 electoral college win over Pete Buttigieg in 2024.

Trump’s first term in the White House had been somewhat redeemed by the fact that he had spent much of it playing golf and rage-tweeting at the television. His second term was less distracted, largely because he remained confined to his quarters – as President Trump had been convicted by a state court, he was unable to pardon himself. As a result, he whiled away his sentence attempting to actually govern, with broadly predictable consequences.

Delaware was the first state to ratify the Constitution in 1787 and became the first state to secede in 2028, shortly after President Trump declared his intention to run for a third term. He did so having engineered the striking down of the 22nd Amendment by a Supreme Court, now lorded over by his latest appointee, Chief Justice Rudolph Giuliani – and, on occasion, by Giuliani’s emotional-support heron, also called Rudolph.

Where Delaware went, others followed – the smaller states of America’s north-east first, followed by the bigger ones of the west coast and the less weird blocs of the Midwest. It was all surprisingly painless and plausible; as was pointed out at the time, even a relative minnow like Rhode Island had a larger population than several European countries. The Republic of California, meanwhile, is now Earth’s fifth-largest economy. And the no-longer-united states have not got along any worse than they did before they became sovereign nations. The former US looks more than anything else like a transatlantic mirror image of the EU; a collection of geographically contiguous yet culturally disparate countries sharing a currency and, since its establishment in 2039, a continental parliament to which nobody really pays attention, except to blame their own problems on it.

Ironically, it was the secession of New York state that trapped Donald Trump properly, marooning him as an inmate of a foreign prison, where he languishes still, a hearty and bellicose 106, consoled by the honorary title of His Majesty Supreme Sovereign Lord Knight Commander Emeritus. This followed the seizure of actual power in 2035 by his son, now Emperor Eric Trump of Magaland – an area that comprises the former state of Florida, plus the spoils of the only armed conflict of America’s disintegration, the brief war in which Florida and Alabama attempted, respectively, to surrender Jacksonville and Birmingham to each other.

Russia’s revolution was perhaps easier to diagnose in 2023, being as it was an eerily precise recurrence of what had upended the country a little over a century earlier: complacent autocracy commits corrupt and incompetent army to a futile war, soldiers start thinking that there might be more to life than serving as cannon fodder for a conflict that they couldn’t care less about, irritable citizenry squabbles among itself for a bit before eventually coalescing around an exiled dissident.

President Alexei Navalny is now not far off exceeding Vladimir Putin’s seemingly interminable tenure in office – and in that respect he has been a disappointment to early admirers who had taken him for some sort of liberal democrat. But merely by dint of not being a total thug, an obvious crook or a maniacal ideologue, Navalny ranks as probably the most enlightened leader that Russia has ever had. It is not only the world’s cartographers and flag manufacturers who have reason to be grateful for his decision not to fight the secessions of Chechnya, Khakassia, Udmurtia, Ingushetia and Tatarstan, or the referendum that saw the Baltic exclave of Kaliningrad vote overwhelmingly for reabsorption into Germany.

China had spent decades not only insulating itself against any sort of devolution, building an astonishingly pervasive surveillance state, and imprisoning millions of members of potentially quarrelsome minorities but not even the People’s Republic could hold out entirely against the global fad for devolution. As President Xi Jinping reiterated Beijing’s eternal dominion over Taiwan at the 2022 National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, few would have thought that 20 years later he would welcome, as an honoured guest to the same conclave, the president of Taiwan, a country that was then in the process of elbowing for space around the already crowded benches of the UN General Assembly. As had often been the case in the post-Cold War years, China appeared to have charted its course by examining what Russia did then doing the opposite. China’s recognition of Taiwan in 2037 was smart thinking, avoiding both a pointless war and an economically damaging international opprobrium – and, indeed, domestic backlash. President Xi understood that it is very usually the case with nationalist grievances that nobody really cares; they merely enjoy the drama associated with pretending to.

As for the country from which this rumination is being filed, it is no longer United, nor a Kingdom. The beginning of the end can be traced to the general election of January 2025. The Conservative Party, having burned through six prime ministers in the previous three years, turned back to Boris Johnson, whose inexplicable hold over enough of the British electorate saw the Tories narrowly elected to a fifth consecutive term. However happy Conservative voters might have been, they were not more delighted than Scottish nationalists, who saw the poll numbers in favour of independence spike every time Johnson warned against it.

Not that he got that many chances. Johnson was obliged to resign again six months into his new term, for reasons we need hardly revisit. After a further seven Tory prime ministers in the ensuing five years, the last of them Rehman Chishti, who at least had the good grace to seem as surprised as anyone else, the incoming Labour government of 2030 granted Scotland its independence without the formality of a referendum – largely, it has to be suspected, on the grounds of embarrassment.

Wales, possibly somewhat giddy following its fourth consecutive World Cup victory in 2034, decamped shortly afterwards, at which even the most adamantine Northern Irish Unionists conceded that the whole set-up was beginning to look ridiculous. The reunification of Ireland was sufficiently smooth as to prompt widespread bemusement re: what the fuss had ever been about. It was nevertheless a surprise in 2042 when King Charles III marked the 20th anniversary of his accession by announcing not only his abdication but also the fact that he had conferred with his son and heir, Prince William, who had decided that he couldn’t be bothered either, sensible fellow. The declaration of the Republic of Cornwall seems to have been regarded as an indignity too far.

The foreign-policy pragmatists of two decades ago would have been horrified by the prospect of this Balkanised new world with the possibility of still further upheaval to come, if the Western Australian Liberation Organisation gets its way. But the reality has always been that wars are caused by people, not borders – and really, our world today in 2043 is by many measures actually more peaceful than that of 2023. Not least because, with so many countries distracted or indeed dismantled by their own domestic turbulence, the constituent nations of the Middle East accepted that if there was no further attention to be wrung from anybody else, they’d best sort their own problems out. You’d have got long odds, 20 years ago, on a Nobel Peace Prize being shared by Israeli president Benjamin Netanyahu and Hezbollah secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah but funnier things had, by then, happened.

About the writer: Mueller is a contributing editor at MONOCLE and hosts Monocle 24’s flagship current-affairs radio show The Foreign Desk.

4.

Daniel H Pink on ...

How looking backwards can help us move forwards – and why political leaders should be allowed to show their vulnerable sides and admit to having learnt from their mistakes.

Regret can be a good thing – if you treat it right. We shouldn’t ignore it or wallow in it. Instead, we should treat it as something that can be transformative. Regret isn’t a positive emotion but you have to wonder: why would an emotion that is so negative also be so ubiquitous? The answer is because it’s useful. Regret can help us become better negotiators and problem solvers; it can help us find more meaning in life.

My latest book, The Power of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward, is not something I would have written in my thirties. I simply didn’t have enough mileage in me then. But now that I’m in my fifties I can look back at the past and know that there are things that I wish I had done differently. So I started thinking about how I could learn from it all.

The past can always teach us about the future. This applies to political contexts too. Our leaders often feel the need to be invulnerable or perfect. I can understand that impulse. Admitting to mistakes can result in them being clobbered on television or social media. But in avoiding this, they might also be making a tactical error.

Research shows that people rarely think less of each other when we reveal our mistakes and vulnerabilities. Politicians should be able to say, “I made a mistake. Here is what I learnt from it and here is what I’m going to do in the future.”

On a broader level, we’re also struggling with collective regret in the US. We must grapple with the fact that our country was founded on slavery. Meanwhile, in our schools, there are big debates concerning how we should talk about race. On the one hand, there are people who think that the past is the past and that we shouldn’t dwell on it. On the other, there are people who think that we are permanently scarred – and that we are irredeemable because of it.

But there is a way to note that there are elements of American history that are not glowing, without simply sweeping them under the rug. As a society, we should be confronting our past and asking ourselves how we can do better as a country. Regret clarifies what our values are and shows us how we can do better.

In some ways, many of us haven’t been taught how to deal with these negative emotions. Americans in particular are often over-indexed on sunniness. That said, people don’t need to feel happy all the time. Our emotions help us survive and they help us to do better. We mustn’t avoid them.

When we look at regret on a collective level, we also often think about the limits of our agency, our ability to change things. Take climate change, for example. Can I personally change the way that the whole world deals with it? No. But, in some ways, that is the wrong question to be asking. Instead, I often ask myself whether I can do one small thing in my own realm. The answer is almost always a resounding “yes”. We can’t always do everything, but can we do something? Absolutely.

Taken from an interview by Carolina Abbott Galvão

About the writer: Pink is a bestselling writer and author of The Power of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward, published by Canongate.

5.

Nihal Arthanayake on ...

Becoming a better conversationalist in 2023 and why learning to have the humility to listen to others is not only a personal choice but also a political one.

In his book Starry Messenger, US astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson wrote that “to deny objective truths is to be scientifically illiterate, not to be ideologically principled”. It is a sentence that also sums up the past six years of political discourse in the West.

We live in strange times, shaped by our need to broadcast our firmly held beliefs and give equal billing to opinions and facts. Certain politicians, commentators, news anchors and anyone with a social- media account have made a virtue of “plain speaking” and “calling it like it is” instead of evidence-based observation. Throughout his book, DeGrasse Tyson implores the reader to look to the principles of science to frame decision-making. He writes that when scientists engage in discussion there are three ways they approach a dialogue: “I am right and you are wrong”, “I am wrong and you are right” or “we are both wrong”. The latter requires humility.

An absolute belief in the truth of your position is a barrier to constructive conversation. The triumph of ideology over pragmatism in public discourse has left reason in ruins. People who cling to the mast of their own opinion are at risk not only of drowning but also dragging the entire ship of public discourse into the unedifying depths of ignorance.

I wrote a book about the art of conversation because I felt that we were losing our grip on what it means to be a conversationalist (someone who is good at – or fond of – dialogue). Good conversation is not just a dinner-party trick either. To truly understand, we need to listen rather than simply respond. Let’s Talk: How to Have Better Conversations could alternatively have been called Let’s Listen and the message is as political as it is personal.

One of my interviewees was former police crisis negotiator and author John Sutherland – a great listener. He summed up his work using a Chinese symbol for listening that implies the need to use not only our ears and eyes but also our empathy; an act of listening that’s all-encompassing. It can be as simple as moving your phone from your field of vision next time you sit down to dinner with a friend. Research indicates that this simple act can increase the quality of your conversation. It is a sign to the person you are with that you value them more than you do a notification about a dog in a costume or the latest prime ministerial resignation.

History offers guidance on better conversations. In the coffee houses of 18th-century London, where conversation and debate were elevated to an art form, divergences of opinion were themselves diversions. Politeness and good manners were also highly prized. What would Samuel Johnson make of how we speak to one another today?

As many in the UK contend with the cost- of-living crisis, poisonous political debate and a lack of clear leadership in government, we need to find a consensus on how to have better conversations and allow ourselves to receive rather than broadcast. A new-year’s resolution worth keeping in 2023? Seek out new ideas and remember that not everyone can be right.

About the writer: Arthanayake is a broadcaster and presenter on BBC Radio 5 Live, and author of Let’s Talk: How to Have Better Conversations, published by Trapeze.